Athletes

as Activists

by Jason McConnell

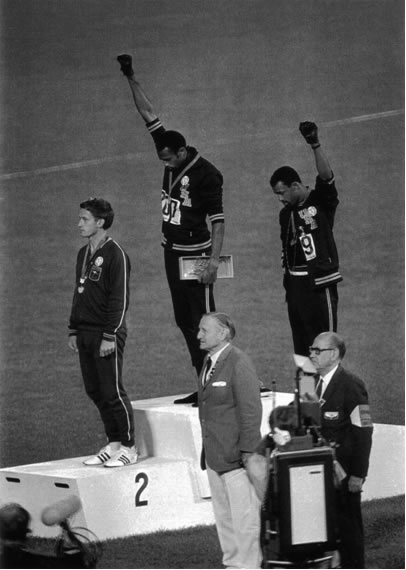

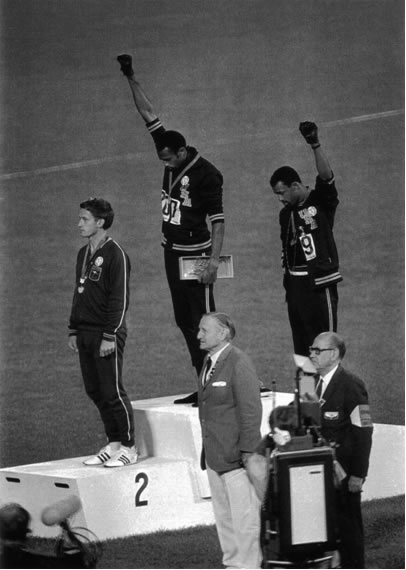

On the second day of the 1968 Mexico City Summer Olympics, after the 200m finals,

Tommie Smith and John Carlos stood on the podium receiving their medals.

The Star Spangled Banner began to play, the American flag was rising on the

pole, and two black gloved fists were held defiantly in the air. Three days

later the two African American athletes were back in the US. Their medals

remained in Mexico. To this day Smith and Carlos's protest is seen as being

a spontaneous act. Portrayed as two independent activists that used the Olympics

as a megaphone in order to call global attention to their cause, they were

spurned, slandered and pushed out onto the fringes of society. Supposedly

they acted apart from their teammates, and stepped outside of the apolitical

box where elite athletes are kept. This misperception continues with the

idea that being stripped of their medals was Smith and Carlos's well-deserved

punishment for their radicalism in an arena bereft of politics. The two sprinters

became scapegoats, representing a phenomenon that in reality was much more

intricate and widespread. They were hyped up and condemned in order to take

the spotlight off of the dozens of other athletes who were increasingly taking

part in the same action: stepping out of the apolitical box they were thrown

into and making political statements for the entire world to hear.

The Olympics are the ideal athletic competition, theoretically providing

for a pure undiluted athletic competition between human beings. 1972 Marathon

gold medalist Frank Shorter noted this in an introduction to a Life magazine

publication prior to the 2004 Athens summer games. In this brief history

of the Olympics Shorter wrote of "the games in ancient Greece, where, during the time

set aside for athletic competition, a universal truce was declared, and mankind's

penchant for war and hostility subsided for a brief moment."1 (Shorter,

pp.6) The original re-creator of the games, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, also

made this observation after the first modern Olympics were held in Athens in

1896: "We shall not have peace until the prejudices that separate the

different races have been outlived. To attain this end what better means than

to bring the youth of all countries periodically together for amicable trials

of muscular strength and agility?" 2 This ideal has proved to be less

than true since the games' reestablishment in Athens in 1896. 'Olympism,' the

ideal of pure athletic competition, certainly does not exist today. The Olympic

Games have, since their reincarnation, been so littered with conflict of all

types that one can scarcely call them Olympic anymore.

In both the Paris and St. Louis summer games in 1900 and 1904, the athletic

competitions were mere adjuncts to a Worlds Fair. In 1908 relations between

the US team and the British hosts quickly became a problem when the US flag

was missing from the Olympic stadium in London. In response to this the American

team refused to bow their flag to the King of England as they marched past

his seat during the opening procession. The 1932 Los Angeles games during the

world wide Great Depression saw an extremely low attendance of athletes since

the games' re-creation. For the obvious economic reasons nations were unwilling

to expend the assets necessary to field a team. Berlin in 1936 saw large scale

media broadcasts of the Olympics that were used as propaganda program to advertise

German technological superiority. In reality the Olympic Games have never been

the ideal they claim to be, but rather have been influenced by many different

external factors that have infiltrated the ideal.

This politicization of the games continued through the first half of the twentieth

century until World War II effectively cancelled the games from 1936 to 1948.

It was after this hiatus that the Olympics began a new type of metamorphosis

into what we now know as the modern Olympic Games. This change occurred in

one of the most controversial periods of time in the twentieth century, beginning

in 1956 in Melbourne with the rise of the US vs. USSR rivalry, and culminating

with the Palestinian/ Israeli hostage crisis in Munich in 1972. However, it

was in 1968 that the world saw the best example of the political circus which

the Olympic Games were destined to become.

In the war torn post-WWII era, the 1948 London games passed with little interest

shown by the world. In the postwar environ however, the games were a good outlet

for national tensions. They offered a safe arena were a nation's athletes could

compete against those of rival nations. This was best embodied by the introduction

of the Soviet Union as a serious competitor during the 1952 games in Helsinki.

The tensions of the Cold War soon made international athletic competition between

the US and USSR extremely political. in Melbourne, 1956 nationalist tensions

and improved global transportation and communication technology marked the

transition of the games into a truly global spectacle. Emphasis shifted from

individual athletes and was placed instead on the methods of calculating national

teams 'scores', or the number of medals the athletes from a particular nation

had won.

The 1960's marked the beginning of televised broadcasting of the Olympic Games. During

1964 the Tokyo summer games and the Innsbruck winter games $1.7 million was

spent on broadcasting rights, but due to time zone differences networks aired

very little live-action coverage of the games. In the 1968 summer and winter

games that figure jumped to $7 million and major networks broadcasted almost

44 total hours of live coverage, 10 of them during prime time television. 3

Although this extra spending did not produce immediate results (interest in

the broadcasts remained fairly low) this increased spending signified a change

in the perception of the Olympics by network executives. The games became prime

time entertainment rather than just a news broadcast.

in Melbourne, 1956 The 1964 Tokyo Olympics were, at their time, the most expensive

Olympics the world had ever seen. The Japanese spent a total of almost two-billion

dollars on making their games the best the world had ever seen at that point.

They accomplished their goal, and turned world opinion in their favor. As the

Mayor of Tokyo Dr. Ryotaro Azuma put it "We were still struggling under

a defeated-enemy-nation syndrome in the eyes of most of the world. Without

the magic of the Olympic name we might have never gotten the investment we

needed to rise again as a world trade power." 4

A US soldier stands on the streets of Washington, DC in

1968

Political Controversy abounded in 1968 in the United States as well as in the

rest of the world. The heated 1968 presidential campaign and the eventual assassination

of Robert Kennedy along with civil rights controversies degrading into violence

after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. made the US a breeding ground

for political radicalism. Public opinion on the Vietnam War turned heavily

against War after the Tet Offensive in the spring of 1968. In France student

protesters were raising the bar in their protests, taking their dissidence

to new levels. During the spring and summer of 1968, a somewhat liberal Communist

regime came to power in Czechoslovakia after the success of the Prague Spring

Revolt. This lead to the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union and

other Warsaw Pact countries and the instilling of a Soviet dominated puppet-government.

Students demonstrating in Mexico against the huge cost of hosting the Olympics

were massacred by the Mexican Army. The massacre in The Plaza of Three Cultures

in Mexico City took place only weeks before the games started. The protest

denounced the huge amounts of money being spent on construction of Olympic

facilities despite the economic conditions in Mexico at the time. They were

protesting what they saw as a betrayal of the Mexican Revolution by an entrenched

bureaucratic party. The Mexican government was at that time trying to use their

hosting of the Olympics to transcend the notion that Mexico a third world nation,

much as the Japanese had been able to do in 1960. The death toll was reported

by the Mexican Government was at around 35, but other estimates range up to

267 dead, and over a thousand wounded. 5

A standoff between Mexican soldiers and student protesters

in the Plaza of Three Cultures, 1968

In previous Olympics, the nation of South Africa had been banned from attending

due to their racist policy of Apartheid. The ban was lifted in the International

Olympic Committee's convention in Tehran, Iran prior to the 1968 Games. The

then Secretary General of the IOC, Col. John Weseroff, gave the news that "An

absolute majority- more than 50 percent of our 71 member nations- have voted

by mailed ballot to approve South Africa's re-entry into the IOC."6 In

protest to this, over thirty Black African countries came together and threatened

to boycott the Olympics. These countries found support for the boycott amongst

the nations of the Caribbean, virtually all Islamic nations, and The Communist

Bloc, most notably the Soviet Union. In response to this the South Africa was

expelled once more. A similar situation occurred concerning Rhodesia after

the nation was condemned by the UN Security Council for their white-dominated

government, even though the had already committed to sending an integrated

team. In reaction to this condemnation, and in response to international pressures,

Mexico refused to accept Rhodesian passports during the games. More situations

where boycott was threatened occurred between the Arab Nations and Israel and

also in the case Indonesia's protest of the inclusion Chinese Nationalist athletes

from Taiwan.

There also was a movement in the United States that was headed by known civil

rights activist Harry Edwards, a sports sociology professor at San Jose State

College, along with other well known athletes such as Tommie Smith and Lee

Evans, which attempted to convince all Black American athletes to boycott the

games. The project, entitled the Olympic Project for Human Rights, was an attempt

to carry the fight for civil rights over into athletics by exposing how the

US used black athletes to project a lie about race relations at home as well

as internationally. Despite winning large amounts of support amongst the people,

particularly students, the OPHR failed to convince a significant number of

African American athletes to give up their chance at Olympic fame, however,

and the games took place as planned. Lee Evans, in an interview in 2005 said

of the 'failed' boycott "Tom [Tommie Smith] and I had talked about it,

and I said, 'Let's say we're going to boycott so we can get some things done,'

but we all knew that we were going to run in Mexico. Push comes to shove we

were going to be there." 7 Nevertheless the mood of black athletes on

the US team was sullen and confrontational.

Avery Brundage

Given the huge amount of conflict raging all over the world it was a wonder

that the 1968 Olympics took place at all. This was in part due to the efforts

of American delegate to and president of the International Olympic Committee

Avery Brundage. Brundage was a notorious white supremacist best known for being

the man who sealed the deal for Hitler hosting the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

It was he who rallied to allow South Africa to be allowed into the '68 games

despite the issue of Apartheid. He ignored requests for the uninviting of the

Soviet Union and it allies after their invasion of Czechoslovakia. Despite

his seemingly biased actions, however, Brundage did do his best to keep the

Olympics alive as a solely athletic competition. An idealist to the core, Brundage

believed in the Olympic ideal, and in a time of troubles he pushed incessantly

to keep the Olympics undiluted and free of political conflict. As he put it "If

participation in sport is to be stopped every time the politicians violate

the laws of humanity, there will never be any international contests."8

It was under this cloud of political storm that the US Olympic Team took to

the field in Mexico City. With their threat of boycott still fresh in their

minds Black American athletes planned their strategies on how best to bring

their cause into the games. In the end it was decided that the decision would

be left to each individual event. That is to say that each group of athletes

would decide how best to protest in their own particular events. The effect

was a rich canvas of political statements made in many different ways by both

black and white athletes.

Many Black American athletes protested in the name of civil rights, but none

gained the notoriety of Tommie Smith and John Carlos. The two were teammates

from San Jose State College, incidentally the same college where Harry Edwards

was a professor of Sports Sociology. The sprinters caught the attention of

the entire world with their impromptu Black Power salute on the awards podium

as they received their medals, one gold medal and one bronze medal. With black

gloved fists and heads turned to the ground, and OPHR buttons on their shirts

to advertise their cause, the two solemnly held their salute during the playing

of the American national anthem, infuriating Avery Brundage and other Olympic

dignitaries. Even the silver medalist, Australian Peter Norman, wore an OPHR

button to show support. For their actions "the two militants" were

stripped of their medals within hours of their protest and kicked off the US

Olympic Team by the United States Olympic Committee.9

One aspect of this infamous protest which often goes unnoticed, which can been

seen all too clearly in the popular photos and posters of the event, is that

in addition to their black leather gloves and bowed heads, Smith and Carlos

are also barefoot, wearing only black socks, protesting black poverty in the

United States. Also, they both wore beads to protest lynching. As John Carlos

said in an interview in 2005:

" We stated we were going to do something. But Tommie and

I didn't know what we were going to do until we got into the tunnel.[On the

way to receive their medals] We had gloves, black shirts, and beads. And we

decided in that tunnel that if we were going out on that stand, we were going

to go out barefooted and...

We wanted the world to know that in Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, South

Central Los Angeles, Chicago, that people were still walking back and forth

in poverty without even the necessary clothes to live. We have kids that don't

have shoes even today. It's not like the powers that be can't provide these

things. They can send a spaceship to the moon, or send a probe to Mars, yet

they can't give shoes? They can't give health care? I'm just not naïve

enough to accept that...

The beads were for those individuals that were lynched, or killed, that no

one said a prayer for, that were hung tarred. It was for those thrown off the

side of the boats in the Middle Passage. All that was in my mind. We didn't

come up there with bombs. We were trying to wake the country up and wake the

world up, too."10

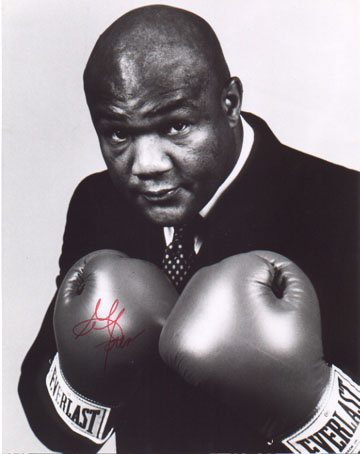

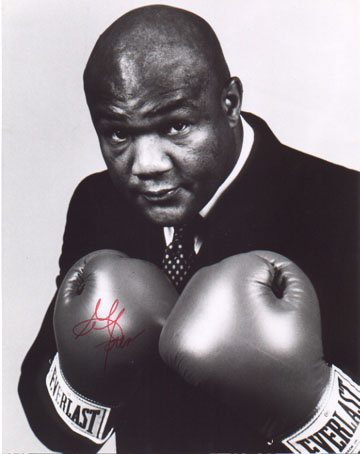

George Foreman

Despite Smith

and Carlos's expulsion from the games, protests continued, though no other

Americans received as much press coverage as the two sprinters. George Foreman

made perhaps the second most infamous political statement by an American

in the 1968 games, one that was seen by many to be in response and opposition

to Smith and Carlos's. After his victory in the heavyweight division of the

boxing competition, Foreman paraded the ring patriotically waving a small

American Flag and bowing to the crowd. This was portrayed by the media as

being a reaction to Smith and Carlos, and Foreman was sensationalized for

it. In reality, however, the flag had no connection with Smith and Carlos.

Foreman was just making his own personal statement, albeit in a different

fashion. When asked whether or not his actions were in response to the sprinters,

Foreman said, "No way.

It was spontaneous and had nothing to do with them. I always carried a small

American Flag--red, white, and blue--with me so that people would know I was

from America. Also it was tradition to bow to each judge after a fight so the

next time you get points." Foreman, who had grown up in poverty said

that he felt he had been "rescued from the gutter by America." 11

The Heavyweight gold medalist from Marshall, Texas was simply celebrating his

escape from poverty, one of the same things that Smith and Carlos's protest

had targeted.

Other Black American athletes made statements that were a bit cleaner cut.

Lee Evans, a 400meter runner, wore a black beret, the symbol of the Black Panther

Party. Members of the US Men's 4x100m sprint relay team did the same, even

going so far as to raise their fists, although they did not wear black gloves.

The legendary African American sprinter Wyomia Tyus and the rest of the US

women's 4x100m sprint relay team even showed their support. Upon receiving

their medals, Tyus spoke for her team when she said "I'd like to say that

we dedicate our relay win to John Carlos and Tommie Smith."12 Bob Beamon,

an American long jumper whose incredible record breaking jump broke the existing

world record by over a foot, showed solidarity. During a second attempt after

his record setting jump Beamon wore a pair of high black socks similar to those

worn by Smith and Carlos on the podium. Support also came from unlikely places,

such as the all white, ivy-league educated US Olympic Rowing Team, who issued

the following statement shortly after Smith and Carlos had been expelled:

"We - as individuals - have been concerned about the place of the black

man in American society in their struggle for equal rights. As members of the

U.S. Olympic team, each of us has come to feel a moral commitment to support

our black teammates in their efforts to dramatize the injustices and inequities

which permeate our society."13

In the aftermath of the 1968 summer Olympics, some of the athletes who had

gained fame through their protests found life to have become a little harder.

John Carlos said of the reaction he recieved when he returned home from the

'68 games,

"There was pride, but only from the less fortunate.

What could they do but show their pride? But we had Black businessmen, we had

Black political caucuses, and they never embraced Tommie smith or John Carlos.

When my wife took her life in 1977, they never said, 'Let me help.'

(Dave Zirin: Did your being an outcast play a role in your

wife taking her life?)

It played a huge role. We were under tremendous economic stress. I took any

job I could find. I wasn't to proud. Menial jobs, security jobs, gardener,

caretaker, whatever I could do to try to make ends meet. We had four children,

and some nights I would have to chop up out furniture and make a fire in the

middle of the room just to stay warm...I was the bad guy, the two-headed dragon

spitting fir. It meant we were all alone." 14

Perhaps George

Foreman described Smith and Carlos's mood the best when he said, "I'll never forget seeing John Carlos walk past the dormitory when

he was sent packing., with all those cameras following him around, and I saw

the most sad look on his face. This was a proud man who always walked with

his head high, and he looked shocked."15

Thirty two years prior to Smith and Carlos's protest on the stand Jesse Owens

made a scene at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. His athletic excellence there

made a statement which, like the one made by Smith and Carlos in Mexico City,

was such that it defied notions of racial inequality in athletics. For his

achievements at the '36 Olympics as well as the apolitical manner he took on

during competition Owens became an icon. When he returned to the US he was

received as a national hero. When Tommie Smith and John Carlos returned home

from their Olympics after making a blatantly political statement they could

hardly keep a job to support their family. Owens, Smith and Carlos all made

a point in the roles they played in their respective Olympics even though their

attitudes dictated extremely different reactions. Their messages were the same.

Racial inequality has no place in society, including in athletic competition.

Lee Evans stated "This is one of the things I learned from Malcolm X and

Martin Luther King. Everybody can play a part, but everyone has to do something."16

Some athletes at the 1968 Olympics gave up their careers and more when they

did try to do something, and in doing so they stepped outside of the apolitical

role that society expected of athletes at that time. They did their part in

the fight for civil rights by taking the struggle into their own particular

arena, shedding the fallacy that athletes must be apolitical for them to be

seen as exceptional. John Carlos was asked the question "Many people say

that athletes should just play and not be heard. What do you say to that?" In

response, Carlos said, "Those people should put all their millions of

dollars together and make a factory that builds athlete-robots. Athletes are

human beings. We have feelings too. How can you ask someone to live in the

world, to exist in the world, and not have something to say about injustice?"17

Jason McConnell

is a senior at The Evergreen State College, Where he runs for both the

Cross Country and Track and Field Teams.

Works Consulted

Arbena, Joseph L. "Mexico City, 1968: The games of the XIXth Olympiad." Historical

Dictionary of the Modern Olympic Movement. Ed. Findling, John E. and Kimberly

D. Pelle. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1996: pp. 139-47.

de Coubertin,

Pierre. "The Olympic Games of 1896." Sport

and International Relations.

Ed. Lowe, Benjamin, David B. Kanin, and Andrew Strenk. Champaign, Illinois:

Stipes Publishing Company, 1978: pp. 118-27.

Edwards, Harry. Sociology of Sport. Homewood, Illinois: The Dorsey Press,

1973

Fraser, C. Gerald. "Black Athletes Are Cautioned Not To Cross Lines." The

New York Times 16 February, 1968: pp.41

Garrison, Lloyd. "South Africa Allowed to Compete in Olympic Games at

Mexico City." The New York Times 16 February, 1968: pp.41

Griffith, Robert and Paula Baker. Major Problems in American History Since

1945. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2001.

Guttmann, Allen. The Olympics: A History of the Modern Games. Chicago: University

of Illinois Press, 2002.

Hano, Arnold. "The Black Rebel Who 'Whitelists' The Olympics." The

New York Times 12 May, 1968: Magazine, pp. SM32

Kanin, David B. A Political History of the Olympic Games. Boulder, Colorado:

Westview Press, 1981.

Litsky, Frank. "Soviet Action Adds to Turmoil for Garden Meet." The

New York Times 16 February, 1968: pp.41

Olsen, Jack. "The Cruel Deception." Sports

Illustrated July 1, 1968.

Senn, Alfred E. Power, Politics, and the Olympic Games. Chicago: Human Kinetics

Press, 1999.

Shorter, Frank. Introduction. The Olympics: From Athens to Athens, An Illustrated

History of the Summer Games by Robert Sullivan. Time Inc. Home Entertainment,

2004: pp. 6-7

Sullivan, Robert. The Olympics: From Athens to Athens, An Illustrated History

of the Summer Games. Time Inc. Home Entertainment, 2004.

Zirin, Dave. What's My Name, Fool?, Sports and Resistance in the United States.

Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005.

1 Frank Shorter's introduction to The Olympics, From Athens to Athens: An Illustrated

History of the Summer Games, pp.6.

2 Baron Pierre Coubertin's article documenting the results of the first modern

Olympic Games in 1896, pp.127

3 Statistics from Alfred Senn's Power, Politics and the

Olympic Games, pp.143

4 From The Olympics: From Athens to Athens, An

Illustrated History of the Summer Games, pp. 82. A brief

description of how the Japanese used the Olympic

Games of 1960 to improve their economic situation.

5 Statistics on the Tlateloco Massacre from Guttman, The Olympics: A History

of the Modern Games, pp.129.

6 From Lloyd Garrison's article in the New York Times, February 16, 1968

7 From chapter four of Dave Zirin's What's My Name, Fool?, a social history

about athletics and political activism in the 1968 Olympics.

8 Avery Brundage's reaction to the Tlateloco Massacre, from Guttman, The Olympics:

A History of the Modern Games, pp.129.

9 From Historical Dictionary of the Modern Olympic Movement, edited by Findling,

John E. and Kimberly D. Pelle. An essay by Joseph Arbena describing the 1968

Olympics.

10 From chapter four of Dave Zirin's

What's My Name, Fool?, an interview

with John Carlos.

11 From chapter four of Dave Zirin's What's My Name, Fool?, grilling George

Foreman about his actions during the 1968 Olympic gold medal heavyweight boxing

match.

12 From chapter four of Dave Zirin's What's My Name, Fool?, Wyomia Tyus and

other athletes' political activism.

13 From chapter four of Dave Zirin's What's My Name, Fool?, support of the

Black athletes' actions during the '68 games.

14 From chapter four of Dave Zirin's What's My Name, Fool?, an interview with

John Carlos.

15 From chapter four of Dave Zirin's What's My Name, Fool?, an interview with

George Foreman.

16 From chapter four of Dave Zirin's What's My Name, Fool?, an interview with

Lee Evans.

17 From chapter four of Dave Zirin's What's My Name, Fool?, an interview with

John Carlos.