Whitney Bard

From fifties

A Little Background on Guatemala

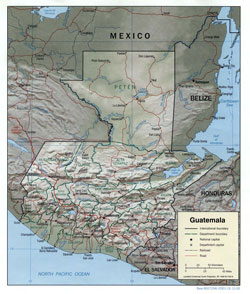

Location: Central America, bordering the North Pacific Ocean, between El Salvador and Mexico, and bordering the Gulf of Honduras (Caribbean Sea) between Honduras and Belize

Natural Resources: petroleum, nickel, rare woods, fish, chicle, hydropower

Ethnic Groups: Mestizo (mixed Amerindian-Spanish - in local Spanish called Ladino) and European 59.4%, K'iche 9.1%, Kaqchikel 8.4%, Mam 7.9%, Q'eqchi 6.3%, other Mayan 8.6%, indigenous non-Mayan 0.2%, other 0.1% (2001 census)

panish 60%, Amerindian languages 40% (23 officially recognized Amerindian languages, including Quiche, Cakchiquel, Kekchi, Mam, Garifuna, and Xinca)

The Mayan civilization flourished in Guatemala and surrounding regions during the first millennium A.D. After almost three centuries as a Spanish colony, Guatemala won its independence in 1821. During the second half of the 20th century, it experienced a variety of military and civilian governments, as well as a 36-year guerrilla war. In 1996, the government signed a peace agreement formally ending the conflict, which had left more than 100,000 people dead and had created, by some estimates, some 1 million refugees.

United Fruit

"Hello Amigo...I'm Chiquita Banana and I've come to say/You eat the banana in a special way/And when it's fleck with brown and has a golden hue/That's when bananas are the best for you...." (Music © 1945 Shawnee Press Inc.)

With its headquarters in Bananera, Guatemala, United Fruit corrupted every level of government and politics, making itself exempt from taxes for 99 years. The company had the unconditional support of right-wing dictators who maintained their power, terrorizing the people and arresting citizens who were either killed on the spot or tortured in prison. The people of Guatemala overthrew the dictator in 1944 and held their first true elections. A new constitution, based on the U.S. constitution, was drawn up. Two percent of the Guatemala population owned over 70 percent of the land and only 10 percent of the land was available for 90 percent of the population. The majority of the land held by the large landowners – United Fruit among them – was unused. The newly elected president, Jacobo Arbenz, redistributed the unused land making it available for the general population to farm, thereby curbing United Fruit’s monopoly on banana farming land. United Fruit, in turn, complained to their friends within the U.S. government including President Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, saying that Guatemala had turned communist (Vanguard Squad).

Jacobo Arbenz

U.S. Involvement in Guatemala

The 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état, a covert operation organized by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency to overthrow Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán, the democratically-elected President of Guatemala. Arbenz's government put forth a number of new policies that the U.S. intelligence community deemed Communist in nature and, suspecting Soviet influence, fueled a fear of Guatemala becoming what Allen Dulles described as a "Soviet beachhead in the western hemisphere" within the CIA and the Eisenhower administration, a concern that found no shortage of believers given the intensely anti-Communist McCarthyism prevalence at the time. Arbenz instigated sweeping land reform acts that antagonized the U.S.-based multinational company United Fruit Company, which had large stakes in the old order of Guatemala and lobbied various levels of U.S. to take action against Arbenz. The operation, put into motion in late 1953 and concluded in 1954, planned to arm and train an ad-hoc "Liberation Army" of about 400 fighters under the command of a then exiled Guatemalan army officer, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, and to use them in conjunction with a complex and largely experimental diplomatic, economic, and propaganda campaign.

The operation was preceded by a plan, never fully implemented, as early as 1951, to supply anti-Arbenz forces with weapons, supplies, and funding, Operation PBFORTUNE. Afterwards there was an operation, Operation PBHISTORY, whose objective was to gather and analyze documents from the Arbenz government that would incriminate Arbenz as a Communist puppet (Wikipedia).

In 1953, under President Eisenhower, the CIA drew up plans for assassinations, sabotage and propaganda to overthrow Arbenz. The assassination list contained the names of at least 58 Guatemalan supporters of Guzman who the CIA suspected were Communists. Late that year, the National Security Council gave Operation Success the go-ahead. The State Department, now led by John Foster Dulles, the brother of the director of central intelligence, Allen Dulles, worked closely with the CIA.

The coup went quickly, from June 16 through June 27, 1954, with radio propaganda and political subversion proving to be the most effective weapons. Arbenz resigned, denounced the United States, and took refuge in Mexico.

CIA plans for Operation Success called for the assassinations, and these plans were discussed in great detail at very high levels of the agency and the State Department, the records show.

No record of the formal approval or disapproval of these plans by Eisenhower or the Dulles brothers has been made public. None likely exists. The newly released files include a 22-page how-to manual on murder that says, "No assassination instructions should ever be written or recorded."

The CIA records show it conducted what it called a "nerve war" against some of these targets -- government officials, "unfriendly army officers" and the like -- in 1953 and 1954. Its plans included sending them death threats; telephoning them, "preferably between 2 and 5 a.m.," with blood-curdling warnings; and denouncing them to their superiors with accusations, ranging "from treason to tax evasion."

And they show that the agency considered the Guatemalan military "the only organized element in Guatemala" through which political change could take place. That change, says a 1953 CIA document, had to begin with the "subversion and defection of army leaders." The agency has had Guatemalan military men on its payroll ever since.

The 1954 coup was the first chapter in the CIA's long and continuing liaison with the Guatemalan military.(Latin American Studies).

Links

|The 1954 CIA Coup in Guatemala|

|Guatemala, United States Assistance, and the Logic of Cold War Dependency|

|Vanguard Squad on United Fruit|

|Bananas: How The United Fruit Company Helped Shape The World|

Bibliography

CIA--The World Factbook--Guatemala. 15 May 2008. CIA. 21 May 2008. [[1]]

The 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état--Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia. 21 May 2008. [[2]]

Shit is Bananas--Vangaurs Squad. Vanguard Squad. 31 May 2008. [[3]]

CIA in 1950's Drew Up List Of Guatemalan Leaders To Be Assasinated. 28 May 1997. Latin American Studies. 31 May 2008. [[4]]

Research Paper

Two Coup D'états: New American Imperialism in the Fifties.

Whitney Bard

In post-WWII, with Europe and the international economy in shambles, the United States gained ground at the sole international superpower. In the history of Imperialism, there have been many rationalizations for the violence and oppression of another tribe, people, race, religion, country or culture: think Columbus, manifest destiny, and other moral justifications like religious or racial superiority. Each Imperial rule occurs with different validations, but the motives are peculiarly similar at the core; the dominating party stands to gain something from the dominated. An Imperial state, nation, tribe or party becomes a parasite of the resources and bounty of the Imperialized—think the rubber trade in the French Congo, or the sugar trade of the Caribbean. The pattern is to move in, dominate, exploit.

The problem with Imperialism is that that the dominator sometimes needs to convince it’s people of the moral soundness of something utterly morally unsound—the totally distasteful subjugation of other human beings for profit. Manifest destiny explained away the spiritual ramifications of senselessly slaughtering Indians to steal their land by positing that God had given preference to some and by being born white and in the U.S. was enough to mean God wanted the U.S. whites to expand Westerly, that it was their obvious purpose by right of birth. Often times, the moral validation comes in the form of instilling fear of the “other”, creating a survival instinct where extreme measures are acceptable. This fear was the tactic employed to muster support in the United States for a new spin on Imperialism in the 1950s: the fear of communism. For a long time, North American corporations had received the support of the United States military abroad. The economic interests of the company run parallel to the economic interests of the U.S.; they are the siphon by which the U.S. is able to vacuum capital from all over the world.

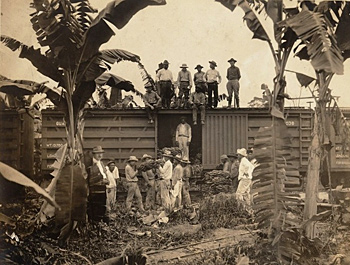

The United Fruit Company was such a siphon from the Caribbean and South and Central America to North America. Beginning from a merger of two competing banana import companies in 1899 (UFCOHistSoc), United Fruit and Standard fruit—Chiquita and Dole brand bananas, respectively— came to dominate the market during the mid-twentieth century (Jenkens, 17), with plantations in with plantations in Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Jamaica, Nicaragua, Panama and Santo Domingo. Even today, Latin American export bananas are overwhelmingly grown in a plantation system dating back to United Fruit’s initial conquests (Frank, 9). Between 1900 and 1917, American troops intervened in Cuba, Panama, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, Mexico and Haiti to protect United States investments and businesses (Jenkens, 19).

In 1903, after separatist groups in the Columbian state of Panama declared independence, the U.S. government sent in troops to defend the separatists from the reclamation of Columbia. As soon as the independence was sealed, the U.S. obtained sovereignty of a strip of land to fulfill plans of an inter-oceanic canal. In the same year, the U.S. military “intervened” in Honduras and the Dominican Republic (UFCOHistSoc). The following year, the United Fruit Company signed a ninety-nine year concession with the Guatemalan dictator, Manuel Estrada Cabrera, to construct a railroad through the country from Guatemala City to Puerto Barrios. This proved to be a useful tactic in gaining ground within the host countries, and the company continued to manipulate or bribe the local governments so that in 1935 the term “banana republic” was used to reference a country controlled by the company, with docile dictators and puppet public officials in the pockets of the company (Jenkens, 20).

The closer one looks at the relationships between the U.S. military and government and the United Fruit Company, the more the lines become blurred: during WWI, UFCO was required to loan thirty-seven of it’s biggest ships in contribution to the war effort (Jenkens, 27). If a government’s underlying economic value system is based in capitalism, the economic system in which “investment in and ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange of wealth is made and maintained chiefly by private individuals or corporations” (Dictionary), it makes perfect sense if that government is in bed with—or in the pockets of—corporations upon whose healthful existence the economy lies.

If these corporations depend on the exploitation of foreign resources, something must be done when the foreign resources seek to withdraw from this unbalanced relationship. One way to ensure the continuation of the exploitation is to take advantage of weak spots and develop dependence upon and un-payable debt to the Imperial power for basic subsistence or economic aid, as in the case of the World Bank’s loans to poor countries One enactment of this tactic is the ensnaring the Imperialized nation in a binding contract, such as the concession for UFCO to build a railroad in Guatemala.

Another is the 1901 concession to search for oil in Iran, which led to the discovery of the vast oil reserves of the Midde East, the profit of which went primarily to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company—now known as British Petroleum. In Iran, after half a century of this inequitable relationship, nationalism in was gaining strength. In 1951, led by the new Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddeq, the oil company was nationalized (Halberstam, 364). The United States, then in heated competition with the Red Menace, feared the communist neighbor to Iran, the Soviets, would take advantage of the vulnerable new government, sent in American diplomats to negotiate a settlement between Iran and the British (Halberstam, 364). It was unsuccessful, and Mosaddeq severed diplomatic ties to England. The British sought help from the United States in reclaiming their highly profitable oil production. As a sympathetic Imperial-capitalist power living in fear of a global shift towards communism—which would equate a devastating loss of profit and power with the withdrawal from its economic colonies—the U.S. was threatened by the nationalization of industry in any form: even if it was in opposition of another Imperial power, perhaps the theories would spread and soon the whole world would be red. However, one could make the argument that nationalization and reclamation of sovereignty over resources has less to do with communism and much more to do with something like the American Revolution—the same idea as taxation without representation.

In 1953, the U.S. utilized the new covert-operations capability of the CIA and orchestrated a haphazard and clandestine coup d'état with the intention of halting the red blush of nationalism rising in the cheeks of the Middle East. employing false mobs and radio manipulations. Calculated by the CIA, the impotent and exiled Shah of Iran dismissed Mosaddeq as Prime Minister and instated a Western-approved Iranian General, Mohammad Fazlollah Zahedi (Zahedid wikipedia).

As the Central Intelligence Agency itself was fairly new, having been established through the National Security Act of 1947 by President Truman (CIAhist), and this was its first foray into covertly orchestrating the over-throw of a government on behalf of corporate interests. It wasn’t the last, and as the years went on, the technique was perfected and elaborated upon.

In the mid-twentieth century, Guatemala was thoroughly held in the vice grip of the United Fruit Company. In addition to owning the country’s railroad system, United Fruit owned the telephone and telegraph facilities, and in 1935United Fruit had signed another ninety-nine year concession with the banana republic’s President General Jorge Ubico in 1935 (UFCOHist), allowing the company virtually free reign to use of land and workers. In 1950 the company’s reported annual profit was $65 million, two times the total revenue of the Guatemalan government (Halberstam, 377). After Ubico, reformist Juan Jose Arevalo Bermejo was elected in 1944, introducing a new set of laws which valued the political participation of the people, education of the illiterate and empowerment of workers. This new kind of government aimed at ending injustice and manifesting the potential of democracy was threatening to the economic interests of United Fruit—if the oppressed people were given an inch, they might take a mile.

Arbenz was accused by the United States of communist ties, although there was little evidence that this was the case. This agrarian reform, like the nationalization of oil production in Iran, was not actual communism but represented the threat of an Imperialized, subjugated colony gaining strength and possible autonomy from the Imperial power. In 1953 the newly appointed American ambassador to Guatemala, Jack Peurifoy, sent a cable to President Eisenhower in Washington, warning, “the candle is burning slowly and surely, and it is only a matter of time before the large American interests will be forced out completely” (Halberstam, 381). To muster support for the coup-in-planning, “Sam the Banana Man” Zemmuray, president of United Fruit hired a public relations firm to “begin an aggressive campaign against Arbenz in the American media” (UFCOHist). In May, 1954, over 100,000 United Fruit Workers in Honduras strike for higher wages, quoting the Universal Declarations of the Rights of Man, and the American Ambassador to Honduras states that the strike was instigated by Guatemalan communists. U.S. secretary of state John Foster Dulles suggests that Arbenz’ government might be behind the strike (UFCHist).

Still glowing with the recent victorious coup d'état in Iran, the CIA—with the help of the autocratic Nicaraguan president Anastasio Somoza García, who was also threatened by Arbenz’ reforms—initiated Operation WASHTUB, an attempt to falsify Guatemalan ties with the Soviet Union by planting Soviet-made weapons off the coast of Nicaragua (Ward, 10). The plan was given little credibility, although Somoza claimed Soviet submarines had been photographed (OpW wikipedia). With tensions heightening from all sides, including from Somoza, and unable to buy arms from Washington, Arbenz did turn to Czechoslovakia, part of the Soviet Bloc, for a supply of weapons, but the CIA was tipped off, and Ambassador Peurifoy intercepted the shipment as it reached the dock in Puerto Barrios (Halberstam, 381). The CIA also utilized psychological warfare of radio manipulations and propaganda dissemination.

A participant in the earlier over-throw of President Ubico, and in a later unsuccessful attempt to topple President Aervalo, Carlos Castillo Armas had escaped prison and fled to the mountains where he trained a rag-tag militia opposing the leftist political changes in his country. The CIA used him as a figurehead to over-throw Arbenz, creating on the radio a sensationalized and imaginary war, “one in which the government troops faltered and refused to fight and in which the liberation troops were relentlessly moving toward Guatemala City” (Halberstam, 385). In reality, both Amras and Arbenz had very little military might and the death toll of the “revolution” was one. Another participant in the struggle, who worked as a volunteer doctor in Guatemala, then organized resistance militias against Armas, was twenty-six year old Ernesto “Che” Guevera. His experiences in the struggle were formative in his philosophies on revolution.

Armas was successful, if barely, in his militia-campaign, and Arbenz resigned and was exiled to Mexico. Armas immediately halted the agrarian reform and legal action against United Fruit (UFCOHist). He outlawed labor unions and leftist political parties, which served to radicalize the left. His glory was brief, however; in 1957 he was assassinated, shot by a guard with unknown motives. In 1960, the longest civil war in Latin American history began, lasting until 1996. It seems, looking back, that there was a hope for positive change at some point during the Arbenz reform years. Che Guevera also fled to Mexico after the coup, where he met and befriended Fidel Castro, who in 1958 overthrew President Batista of Cuba by means of guerrilla revolutionary tactics, enacting, among other things, agrarian reform and seizing United Fruit’s sugar plantation land in Cuba.

Obviously, the exploitation of Imperialism is not a sustainable resource. It is continued to this day, but the shape-shifting of Imperialism is fairly transparent if looked at closely; the demonization of President Hugo Chavez in Venezuela draws creepy parallels to the threat the United States felts from agrarian reform from Arbenz. The term Communist in many ways has been reborn as Terrorist, serving much the same purpose of instilling fear and justifying war, exploitation and colonialism.

Bibliography

United Fruit Historical Society—Chronology. 2006. United Fruit. 04 June 2008. [5]

Jenkens, Virgina Scott. Bananas, An American History. New York: Smithsonian Institute, 2005.

Frank, Dana. Bananeras, Women Transforming the Banana Unions of Latin America. Cambridge: South End Press, 2005.

Dictionary.com—definition of “capitalism. 2006. Dictionary. 04 June 2008. [6]

Halberstam, David. The Fifties. New York: Ballantine Books, 1993.

Mohammad Fazlollah Zahedi—Wikipedia. 20 April 2008. 04 June 2008. [7]

History of the CIA—CIA Website. June 02 2008. CIA. June 04 2008. [8]

Ward, Matthew.Washington Unmakes Guatemala, 1954. Washington, D.C.: The Council of Hemispheric Affairs, 2004.

Operation WASHTUB—Wikipedia. 14 April 2008. 04 June 2008. [9]