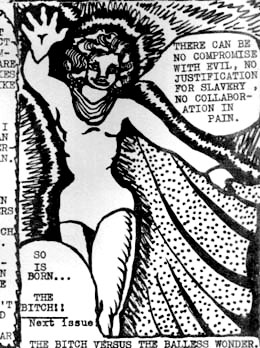

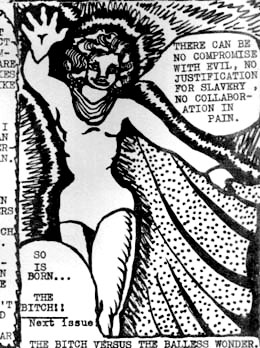

Long, Priscilla. Image from Lilith, courtesy of Dottie DeCoster. 1968.

Remaking a Cultural Mindset: Radical Feminisms in the Pacific Northwest

by Diana Carlson

In 1964, Dotty DeCoster was a twenty year-old single woman living in Seattle. As an unmarried woman, she could not sign a legal contract to obtain a lease on an apartment, obtain medical care or rent a car. It was illegal for her to purchase birth control before the age of twenty-one at which time her husband would be expected to buy it for her. She did not have access to legal abortion services. She and her partner would only be allowed to cohabit under a rental agreement if they were married. “The restrictions put upon women at that time were very different than they are now. Fortunately people have forgotten them, and I think that’s wonderful. But I had to live with them.” When I asked my friend Genne if she was enjoying the television show Mad Men, she expressed a similar sentiment. She said something surprising, “No, I don’t like it. I don’t need to see it. I had to live it.” Feminists succeeded in creating dramatic changes to the status quo for women in the late 60s, and it is understandable that some might want to forget that a repressive gender dynamic was the norm a short time ago. At the same time, it is important for women to not forget, to see the struggles that have gone before them, to learn from the past, and to apply that knowledge to current movements for a more just society.

A political radical, DeCoster was involved with “old guard” leftist groups like the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), and experienced the sexism within them. “It is almost impossible to imagine what it was like in the mid-to late 60s if you were a woman. If you went to a radical meeting you weren’t allowed to talk.” Like other women at the time, DeCoster began to see the need for a separate space for women to exchange ideas. Through the Free University, DeCoster encountered discussion around “the woman question”, became part of the anarchist Women’s Majority Union, and worked on the feminist journal Lilith. Quickly, radical women’s groups surfaced which were addressing the problems that mattered to them, driving the changes which would grant women further autonomy.

Long, Priscilla. Image from Lilith, courtesy of Dottie DeCoster. 1968.

As DeCoster became a young mother and student, she developed an interest in the issue of childcare. She recognized the inherent difficulty for women managing their families and finding time and support for making childcare accessible within state funded institutions. Groups like Seattle Radical Women (SRW) gathered to listen to women’s concerns and eventually worked to promote legislation that would change women’s lives for the better. Childcare access, abortion rights, and no-fault divorce gave women agency over their own lives.

Women in the Pacific Northwest benefited from a strong leftist presence which supported the formation of radical women’s groups like SRW. Radical groups were interested in tackling issues of oppression related to class, race and gender. Attracting national attention to the women’s movement was also an important part of creating broad institutional change. The National Organization for Women, which was founded in 1966 in part by Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique,had mainstream appeal. Her book has been repeatedly criticized for its narrow view, and its intended audience of white, middle-class American women, which left some feeling marginalized. Nevertheless, the mystique was a phenomenon which penetrated many women’s lives, and influenced middle-class housewives and working-class women alike, promoting an interest in women’s rights and giving rise to various styles of feminist thought.

In her account, In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution,Susan Brownmiller describes her experience of trying to establish a voice within the male dominated world of journalism. She was moved by Friedan’s book, and inspired to take action. When her attempts to join the organization were rebuffed, (Friedan initially established the group as a “select committee of professional women who would lobby congress.” ) Brownmiller was disappointed, as she felt that her role as a civil rights activist more than qualified her for a voice within the organization. By the next year, membership had opened up to the general public; Brownmiller had lost interest, dubbing it too “clubwomanish.”

NOW was a traditional organization, open to both men and women, and was an integral part of the women’s movement, working closely with lawmakers and highly motivated to enhance women’s participation in public life. The radical element of the women’s movement, which Brownmiller personally identified with, was working toward somewhat different goals, with a revolutionary agenda focused on challenging basic assumptions about the social order. The NOW was committed to “more traditional forms of protest” such as lobbying for policy reform, and pushing a targeted agenda of equal opportunity in the workplace. The radical aspect of the movement tended to be less organized and more focused on “theoretical papers, imaginative confrontations, and inventive direct action” . Radicals worked to prevent violence against women, addressed issues of gender, race and sexual identity and engaged in inventive forms of consciousness-raising. Creating change requires consensus, and radicals worked with and within the National Organization for Women to promote basic shared goals such as abortion rights.

Connecting with other women and sharing ideas was crucial to changing the social order. Gayla Goller, vice president of the Tacoma National Organization for Women in 1972 is quoted, “There was a picture in the (black history) book of white slave traders looking at a black woman’s arms, teeth and body, deciding whether or not to buy. I glanced up and saw one of the pageant contestants walking across the stage and I thought, ‘we haven’t come very far.’” She goes on to discuss concerns about narrowly defined roles for women. One of the main goals of the Tacoma NOW was to create a body of women working together for change. She adds, “When women unite, people will have to listen to us.”

Alice Echols in Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975 describes the different factions within the feminist movement. “Radical feminism rejected both the politico position that socialist revolution would bring about women’s liberation and the liberal feminist solution of integrating women into the public sphere.” She argues that radical feminists existed somewhere between the leftist Marxian agenda and the liberal feminists who wanted to integrate women into the male-dominated system. What Echols refers to as “cultural feminism” subsumed the radical agenda, wherein rather than attempt to break down the social order, women would find ways to exist within the patriarchy. Echols argues that cultural feminism as it exists today, aims to “celebrate femaleness” , rather than the radical notion of eliminating gender barriers. This shift away from radical ideas can work against change, as it reinforces gender differences which often play out as gender inequality. What is left out of the popular consensus on second-wave feminism is the fact that radicals were indeed focused on social justice from many different angles, seriously challenging the social order, and not just for the elite.

Central to the radical movement was the process of consciousness-raising. Brownmiller defines the practice as “a group exercise designed to unlock the door to collective truths unmediated by the opinions of men.” Women needed the freedom to speak about issues that mattered to them, to share ideas and discover common concerns. Many women who had been active in the civil rights and New Left movement report that their voices were not being given adequate attention within male-dominated organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), CORE, and Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Various accounts report that within the radical and counterculture movement of the late 60s, gender inequality existed even where other barriers were aggressively being challenged.

Deconstructing the basic problems of racism, exploitation and industrial capitalism, radicals still dealt with a difficult gender dynamic. Stokely Carmichael, as leader of the SNCC reportedly remarked, “What is the position of women in SNCC? The position of women in SNCC is prone.” Brownmiller writes about SDS, “Men made policy and speeches while women stuffed envelopes and made dinner.” Many began to feel that their contributions were being ignored, or that they simply did not have a forum in which to air grievances, to brainstorm about solutions or to just “rap” about the cultural boundaries to revolution. They needed to develop new organizations to educate and benefit from each other’s experiences. Writing was one outlet for some as a way to communicate, and popular journals began to surface as a way for women to reach out into their communities.

Pandora was published in Seattle from 1970 to 1976. An independently produced newsletter on the women’s movement, the aim of Pandora was “to maintain communication and sisterhood among the various groups, and to give fair and accurate coverage to events and projects which concern women’s struggle for equality.” Newsletters such as this one were an important aspect of consciousness-raising, a way for women to make new connections, keep track of meeting spaces, and find groups which focused on a specific agenda. Many journals of this type were published in Seattle during this time including And Ain’t I A Woman, a Women’s Liberation Seattle newsletter, Lilith, and national journals such as Sabot, Know, Inc., Off Our Backs and The Pedestal. Pandora was important for women, as it dealt with issues not commonly found in mainstream media. “The myth that women secretly want to be raped and usually provoke it” headlines an article from a 1972 edition. Rape within marriage was not yet legally defined as such, and this was one of the issues related to violence against women that groups were working with. Women of this time were instructed to yell “fire” instead of “rape” because the former would presumably have been taken more seriously. The same issue includes a survival sheet for rape victims. This type of writing was a movement in itself in that women could have access to taboo topics, and learn where they might find like-minded individuals who were willing to provide education and support. Journals brought women together, providing the space to articulate changes that were needed to improve lives. Newsletters like Pandora were important in that they gave public voice to otherwise unrecognized concerns, and created cohesion among various groups which had sometimes conflicting ideologies.

The Pacific Northwest radical movement was a complex one, with different influences and generational disputes. The Freedom Socialist Party was the first group to integrate Marxian and feminist ideology, from which was founded Seattle Radical Women. SRW argued for socialism as the path to reform. Critical of society for its belief that women were historically oppressed due to biological differences, the Radical Women Manifesto, originally distributed in 1967, argued that sexism was rooted in an inherently exploitative economic system. Women were being dominated by men within every class and ethnic group, and the way out was through a revolution of the capitalist system, which treated women as commodities. They were also concerned with the elitist tone of the mainstream women’s movement.

“The current leadership of the women’s movement is largely student, professional, middle-class and white. But its future leadership will emerge from the vast ranks of militant women from the working class and from ethnic and sexual minorities…They develop a keener awareness and consciousness of the triple nature of oppression -- class, race, and sex -- than is possible for most white, non-working, middle-class women.”

FSP and Seattle Radical Women made the region a unique place for new left radical groups to emerge, and popular support from older radicals could be found for a new generation of women interested in “the woman question.”

In her memoir piece, Primary and Secondary Contradictions in Seattle: 1967-1969, Barbra Winslow explains some of the intricacies of the women’s liberation scene in the Seattle area. She echoes the sentiment of other women of her time when chronicling the early days of the movement. “When I tell stories to younger women… they can’t even believe a world like that once existed.” A graduate student at the University of Washington in 1968, Winslow was a radical and civil rights activist when she became involved with FSP, SRW and later, Women’s Liberation Seattle. Interest in women’s history, “the woman question” of Marxism and a strong support for abortion rights led Winslow to the women’s liberation movement. The sexism she experienced in her personal and professional life helped her to find her voice and to actively work to change aspects of a culture which systematically oppressed women.

Ludwig, Steve. Barbara Winslow, campus protest against the ROTC. 1969.

Winslow shares some of her experiences which moved her to activism. She endured the difficult process of obtaining a “semilegal” abortion in Europe, in which she was forced to convince a psychiatrist to sign off on the procedure, having to prove that by carrying the pregnancy to term, she would surely be driven to insanity. She was quite aware that though difficult and painful, many women in the United States did not have even this option. Abortion was available to the wealthy, but not so for the majority of women who needed the procedure to be safe, legal and accessible.

Later, early in her marriage, Winslow writes that she discovered a lump in her breast. At the time, the procedure was to perform a biopsy, and if the lump was found to be malignant, a full mastectomy would be immediately performed. Permission for the procedure was to be granted by her spouse. As the young couple questioned the doctor they were told that “women are too emotionally and irrationally tied to their breasts” and that it would be better for her husband to sign the form. Given that at this time the vast majority of doctors were men, women’s bodies seemed to be out of their own control.

It was a 1968 University of Washington Men’s Day event that moved Winslow to speak out actively for women’s rights for the first time. Radical Women wanted to protest the appearance of a Playboy bunny at the event. The protest, involving women approaching the stage with paper bags over their heads and chanting, was intended to raise the issue of objectification of women’s bodies. The protest was met with anger from the audience of men and women, with some of the women physically attacked. Winslow, who was not completely behind the original vision of the protest, felt compelled to speak up. She took the microphone and attempted to explain to an unreceptive audience the purpose and goals of the women’s liberation movement. Disciplined by campus officials and rebuked by women and men in the audience, Winslow nevertheless discovered that she could speak to women’s issues in a way that she had not previously known.

A series of interviews with Winslow is available via the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, and she is currently working on a book project detailing her experiences. She challenges much of the scholarly work that has been done on the women’s liberation movement, particularly the popular assertion that second wavers failed to address the problems of non-white, working class women. She also notes that the strength of the Old Left in Seattle laid a solid foundation for younger women’s liberation groups to flourish. She argues that Seattle was isolated from some of the disputes which plagued the radical movement elsewhere, which contributed to successful collective action.

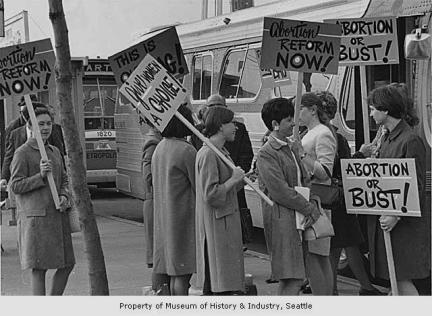

Brownmiller also addresses the importance of the Pacific Northwest region in understanding the movement. Abortion rights were an issue of great importance that united various factions, and demonstrated women’s ability to create real change by working together. Washington State was the first to enact abortion rights by popular vote of the people. Brownmiller describes the two prominent groups, Seattle Radical Women and Women’s Liberation - Seattle, as generally conflicting groups which came together over the common cause of abortion rights. Both groups played an important part in shifting legislation that would give women safe, legal access to abortion services. Slogans which rallied women together included “Abortion Is a Woman’s Right.” Pamphlet distribution on the topic of abortion contained the tag line, “One Out of Four of Us Has Had or Will Have an Abortion,” and was circulated in the thousands. The bill, which had support from local medical professionals canvassed neighborhoods around the state getting word out about proposed Referendum 20. Its success was a tangible reward for collective action which demonstrated the invaluable rewards of working together.

Eagan, Timothy. Abortion Reform Demonstration, Seattle. 1970.

One of the more recent indications of the impact of the radical feminist movement in the Pacific Northwest were the Riot Grrrl groups of the 1990s. Olympia, Washington was an important locale for these women who were disenchanted with outdated gender roles they found in the punk music scene. The movement “was a patchwork of rap sessions, homemade zines…garage bands and guerilla theatre.” Women found an outlet for their rage against misogynistic tropes found in the mainstream music industry and among their male punk peers. There is a marked similarity here between the Riot Grrrl movement and the radical women of the 60s counterculture era. Both encountered male dominated movements which somehow managed to forge ahead without questioning traditional gender roles. Riot Grrrls resisted big media influences, and unfortunately were cast in a negative light, with their original vision clouded by the considerably less revolutionary “Girl Power” trend which had a far more corporate flavor. Still, they engaged in acts of rebellion and created something for themselves which undoubtedly impacted their further efforts, and affirmed that there are alternatives to the dominant culture for women.

Popularly criticized for failing to address the needs of all women, it is useful to think of the complex second-wave movement and all of its factions as feminisms, rather than one all-encompassing theory or group. The Feminine Mystique and the consequent rise of the NOW have an important place in the history of feminism, but cannot fairly be used to illustrate the entirety of the second-wave movement. The radical feminist agenda was a revolutionary one which had a powerful influence on mainstream feminist goals. Equal rights legislation and social reforms were achieved in large part due to the collaboration between women with access to lobbying power and young radicals who participated in massive education and rallying efforts on behalf of women’s liberation. Radicals ultimately sought to break down oppressive structures related to gender, class, race and sexuality, but suffered from organizational disputes and a less defined agenda. It is worthwhile to remember the influence of radical feminism, and to examine the ways it continues to inspire grass-roots feminist efforts from the current work of Radical Women to third-wave Riot Grrrls who continue to engage the world from a feminist stance.

Works Cited

Anderson, Barbara. “Status of Women Aired by Women Voter's League.” Tacoma News Tribune 27 Mar. 1972. Print.

Brownmiller, Susan. In Our Time: Memoir of a Revolution. New York: Dial, 1999. Print.

Crow, Barbara A. Radical Feminism: A Documentary Reader. New York: New York UP, 2000. Print.

DuPlessis, Rachel Blau., and Ann Barr Snitow. The Feminist Memoir Project: Voices from Women's Liberation. New York: Three Rivers, 1998. Print.

Eagan, Timothy. Abortion Reform Demonstration, Seattle. 1970. Museum of History & Industry, Seattle. University Libraries: University of Washington. 30 Jan 2011 <http://content.lib.washington.edu/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CISOROOT=%2Fimlsmohai&CISOPTR=108&DMSCALE=100&DMWIDTH=700&DMHEIGHT=511.875&DMMODE=viewer&DMFULL=1&DMX=0&DMY=0&DMTEXT=&DMTHUMB=0&REC=1&DMROTATE=0&x=181&y=450>.

Echols, Alice. Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-1975. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1989. Print.

Freeman, Sidney, Jeanne Manegold, and Lee Mayfield. Pandora [Seattle] 18 Oct. 1970, Vol I No. 1 ed. Print.

"Issues." NARAL Pro-Choice Washington. Web. 30 Jan. 2011. <http://www.prochoicewashington.org/issues/>.

Long, Priscilla. Image from Lilith, a Seattle women’s liberation magazine, courtesy of Dottie DeCoster. Fall 1968. HistoryLink.org. 30 Jan 2011 <http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=2320>.

Ludwig, Steve. Barbara Winslow, left, taking part in the March 6 campus protest against the ROTC. 1969. Antiwar and Radical History Project. 5 Feb 2011 <http://depts.washington.edu/labpics/repository/v/antiwar/ludwig/ludwig0056.jpg.html>.

Martin, Gloria. Socialist Feminism the First Decade 1966-1976. [S.l.]: Red Letter, 1986. Print.

"Oral Histories: B. Winslow." UW Departments Web Server. Web. 10 Nov. 2010. <http://depts.washington.edu/antiwar/interview_winslow.shtml>.

Stannard, Meredith. “Women Speak out on Rape.” Pandora [Seattle] 2 May 1972, Vol II No. 15 ed. Print.

Wolfe, Allison. "Reconsidering Riot Grrrl" New York Press - the Premier Alternative Weekly in New York City. Web. 21 Feb. 2011. <http://www.nypress.com/article-21671-reconsidering-riot-grrrl.html>.

Zeisler, Andi. Feminism and Pop Culture. Berkeley, CA: Seal, 2008. Print.

Anderson, Barbara. “Status of Women Aired by Women Voter’s Leauge.” Tacoma News Tribune 27 Mar. 1972. Print.

Echols, Alice. Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-1975. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1989. Print.

Freeman, Sidney, Jeanne Manegold, and Lee Mayfield. Pandora [Seattle] 18 Oct. 1970, Vol I No I ed. Print.

Stannard, Meredith. “Women Speak out on Rape.” Pandora [Seattle] 2 May 1972, Vol II No. 15 ed. Print.

DuPlessis, Rachel Blau., and Ann Barr Snitow. The Feminist Memoir Project: Voices from Women's Liberation. New York: Three Rivers, 1998. Print. 230.