Hypocrisy and Empty Promises

by Kristine Boisen

“We are not exaggerating when we say that the American Negro is damned tired of spilling his blood for empty promises of better days. Why die for democracy for some foreign country when we don’t even have it here?”

This is how the editor of the Chicago Defender described the sentiments of blacks in America during World War II. The freedom supposedly being fought for was something black Americans could only dream about. During World War II, a mere seventy years ago, the United States military included soldiers who did not have the same rights and privileges as the people they were defending. Imagine being asked to risk your life for someone else who lived your dream. While there were many ethnic groups in the United States who faced discrimination, the focus here will be on the black soldiers of the United States military.

While thousands fought for equality, Judge William Hastie and the men who became known as the Tuskegee Airmen turned out to be major players in the battle for a desegregated military. They were persistent in their belief that blacks had the right to serve in the military in whatever capacity they chose. The Tuskegee Airmen fought to prove they were every bit as patriotic as the whites and were just as deserving of equal rights in this “land of the free and home of the brave”.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (“NAACP”) was established in 1909 to ensure a society in which all individuals have equal rights. The NAACP issued a statement at the beginning of World War II that:

“Though thirteen million Negroes have more often than not been denied democracy, they are American citizens and will as in every war give unqualified support to the protection of their country. At the same time we shall not abate one iota our struggle for full citizenship rights here in the United States. We will fight but we demand the right to fight as equals in every branch of military, navy and aviation services.”

The United States military is seen as a disciplined, just organization. This, for the most part may be true, but the military is also a reflection of society due to the fact that it is made up of human beings. Each individual in the military has his or her own thoughts, feelings and prejudices.

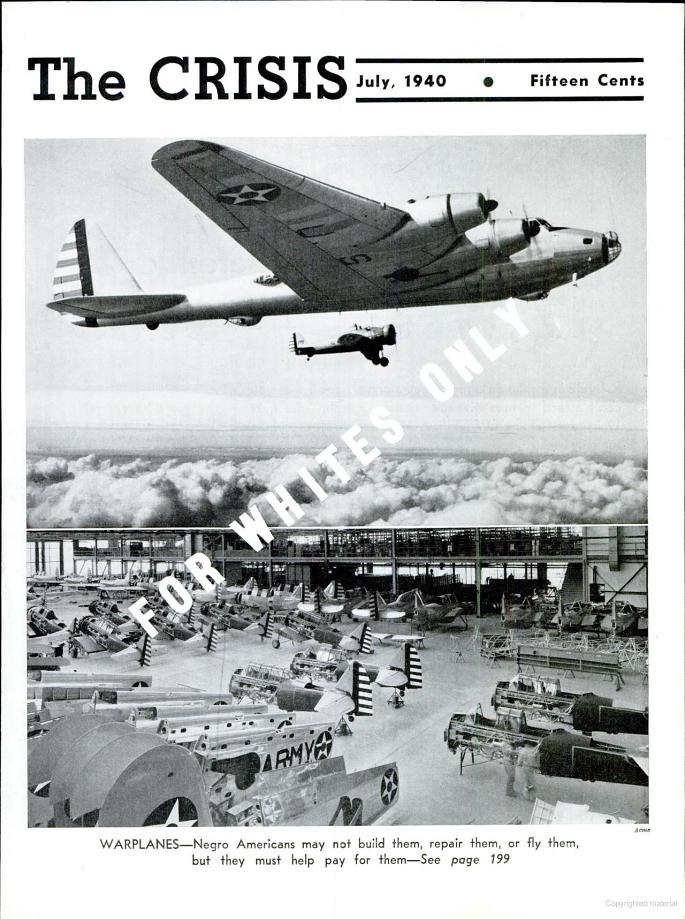

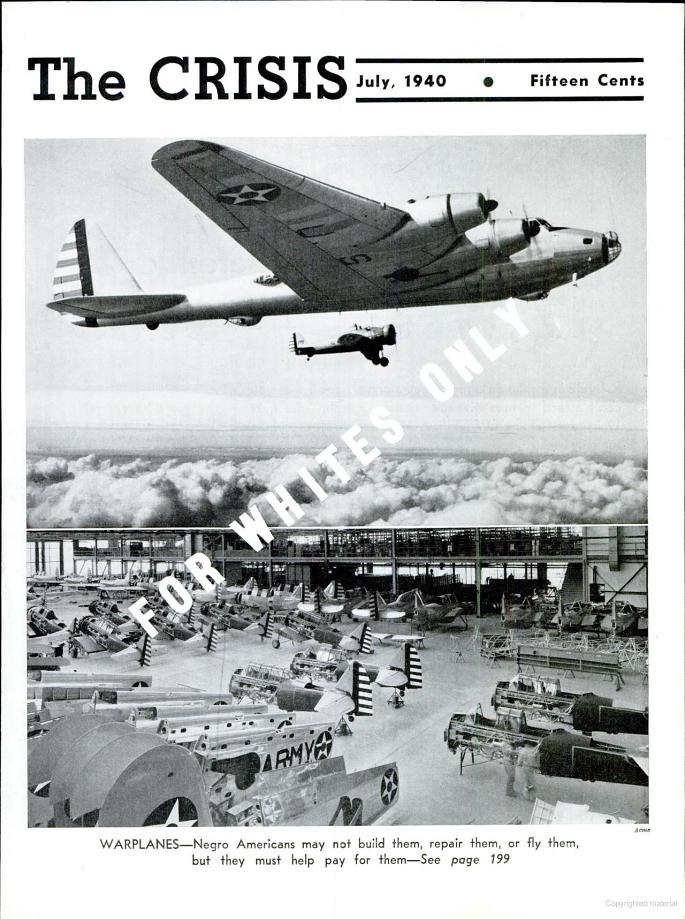

In 1910, the NAACP hired W.E.B. DuBois as Director of Publicity and Research. Five months later, The Crisis magazine was published for the first time. The Crisis is one of the oldest black periodicals in the United States and is considered to be the voice for civil rights. Readership of The Crisis expanded quickly and it is a quality publication to this day. The subject of segregation in the military is reflected on the cover of the July, 1940 issue of The Crisis magazine. The cover shows military airplanes with the words “For Whites Only”.

Figure 1 July 1940 Crisis Cover Page

Richard Dalfiume wrote a journal article entitled Military Segregation and the 1940 Presidential Election in which he states:

“The restrictive attitude of the various armed services was the result of a racist stereotype of Negro servicemen that had been fully developed during World War I and perpetuated thereafter. The basis of the stereotype was the belief that as soldier Negroes were inferior to whites: they were inherent cowards and therefore unsuited for combat roles; they lacked mechanical ability and were therefore unsuited for technical roles. On the other hand, Negroes were thought to be ‘peculiarly suited’ for labor and service duties.” (Emphasis mine.)

Segregation in the military was seen as necessary because of the segregation in society at large. As such, blacks and whites were kept separate informally in the North and West and formally by law in the South. Blacks were never put in command over white soldiers, partly because of the belief that blacks were inferior to whites. This meant that even the most talented, highly educated black soldiers would not be able to advance into any number of positions in the military. Soldiers of the caliber and education of Benjamin O. Davis who graduated from West Point in 1936 suffered because of prejudice and segregation. Davis showed great tenacity during his time at West Point; he as silenced during the four years. Nobody would speak to him unless it was in the line of duty, but he persevered and graduated. After graduating, Davis was not allowed to command white soldiers while the military was segregated.

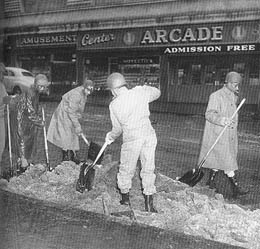

Figure 2 - Soldiers shoveling snow in Seattle

Blacks were often assigned to positions that required hard labor or were in the kitchen regardless of their level of education, while the Marine Corps and Army Air Corps excluded them completely. At Seattle’s Fort Lawton, as historian Quintard Taylor explained, black soldiers were subjected to treatment they found humiliating: “Their complaints included the Army’s exclusive use of black soldiers to shovel snow in Seattle and their confinement to a single base tavern and PX while Italian prisoners of war were allowed outings to Mount Rainier and supervised visits to local bars that excluded black soldiers.”

The Navy had a segregated training facility at the Great Lakes Naval Station. There, men were trained in personal hygiene, cleaning, marching, drilling, guard duty and rifle range training. The sailors at Great Lakes Naval Station received no training in ammunition handling.

Another prime example of the segregation was the Port Chicago navy base. The black soldiers assigned to the base were all assigned to physically handle the bombs and boxes of ammunition, even though they had received no training in the handling of ammunition. All of the commissioned officers, guards and civilian skilled workers were white. Essentially, it was a Jim Crow base. Unfortunately, there was a disaster at Port Chicago, California and a large number of black sailors were killed. On July 17, 1944, there was a terrible explosion during the loading of ammunition. The blast from the explosion destroyed two cargo ships, wrecked the base and caused damage in the town of Port Chicago over a mile away. Three hundred and twenty men were killed in this explosion and of this 320, 202 were black. These men had received no advance training in the handling of ammunition and their time off was dictated by how quickly the men loaded the ships each day. A Naval Court of Inquiry determined that the explosion was the fault of the black sailors who were killed in the explosion. The white officers responsible for leading the operations were cleared of responsibility. To make matters worse, the surviving black sailors were denied survivors’ leave and were immediately reassigned to another base to handle ammunition. Many of the men refused to continue working these same jobs and fifty of them were tried and charged with mutiny.

Mary McLeod Bethune, an official of the National Youth Administration, made the following statement regarding the treatment of blacks during World War II:

“Soldiers in uniform denied food for 22 hours because no restaurant would serve them—a government worker beaten over the head because he attempted to enter a cafeteria that a guard felt should be reserved exclusively for white workers—unarmed soldiers shot on little or no provocation by civil and military police—one group of draftees being examined and inoculated in the boiler room, while other draftees are, at the same time, examined and inoculated in the immaculately clean and white clinic rooms of the induction center. All the victims Negroes--none of the perpetrators of these insults and crimes punished!”

SEGREGATED EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT

Segregation pervaded every area of life for blacks in the United States at the time of World War II. Blacks were segregated into their own schools that were given significantly less funding than schools for white children. For example, while the state of Alabama spent $37 on each white child in public school, it spent only $7 for the education of each black child. Children of black farmers and sharecroppers in the south often spent as few as 74 days a year in school with teachers who were poorly trained. Black teachers were so poorly trained and educated that their average score on a Stanford Achievement test was below that of ninth grade students on a national level.

There was also the issue of job discrimination. Blacks earned significantly less money than whites and as such, were undernourished. With regard to the military, the factors of poor education and lack of proper nutrition meant that black soldiers could not pass the tests necessary to advance in the military or to become officers. The tests measured knowledge of terms, reading skills, physical strength and agility. During World War II proportionally more blacks than whites volunteered for military service. The Selective Service rejections rates for blacks were considerably higher than for whites, 50% versus the 30% for whites. In addition, because so many more whites than blacks had skilled jobs, they were often deferred which meant many more blacks than whites were drafted.

Leisure time for black soldiers was also affected by segregation. The different activities on base were often labeled for “whites only”. Going into a nearby town for recreation often meant the risk of being attacked or worse, being lynched. Even in Tuskegee, Alabama, home of Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, black soldiers were warned that they should not leave the base because of the threat of being lynched.

Dining facilities on base were segregated, or as in the case of the War Department in Washington DC, blacks were provided no dining facilities at all. General Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., fasted his lunch due to the lack of dining facilities rather than eating in the segregated restaurants nearby. On the Port Chicago Naval Base, white sailors ate upstairs while the black sailors were forced to eat in the basement. At one point, even the blood banks of the Red Cross were segregated to insure that white men were never given the blood of a black man.

HOW DID THIS HAPPEN?

How did America, the land of the free and the brave, become a country mired in the hateful sands of segregation? Because of the history of slavery in the United States, it would be natural to assume that is where the problem began. A review of history, however, shows that the problem as we know it really began with a series of Supreme Court decisions in the late 1800’s, ending with Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that cemented the “separate but equal” doctrine. From that point, it took almost sixty years for the Court to return to the principle that equality is indivisible when it ruled on Brown v. The Board of Education. The Court recognized that it is not possible to have equality and compulsory segregation at the same time. We all know that once the Supreme Court establishes a precedent, it does not easily depart from it. While the Court “can change the validity of laws in the twinkling of an eye” the consequences remain. The attitudes, ways of thinking and actions that developed while the law was in effect change much more slowly.

TUSKEGEE EXPERIMENT

In 1940 President Franklin Roosevelt directed the War Department to prepare a statement of policy with regard to equal opportunities for black men in the United States Military. On October 9, 1940, President Roosevelt approved a policy report which stated that blacks would be given jobs in the military on a fair and equitable basis. It went on to state that blacks would be trained as pilots, mechanics and technical specialists. The War Department appointed Judge William Hastie who was the Dean of Howard University Law School to the position of Civilian Aide on Negro Affairs.

Judge Hastie soon found that many decisions regarding Negroes in the military were made before his office was even made aware of them, even though his job was to comment on proposed actions. He protested this process and those in authority issued a directive that Judge Hastie would give his opinion before decisions were made. Judge Hastie pushed the military to follow through on their promise that blacks would be trained as pilots. In December a proposal was given to Hastie containing three potential sites for a training facility for blacks to become pilots. One site was in Texas, another on the West Coast and the third was in Tuskegee, Alabama, in conjunction with the Tuskegee Institute.

Hastie recommended that the military move forward with the plans to locate the black pilot training program on the West Coast because of the race issues in both Texas and Alabama. The whites who lived in Tuskegee fought against the plan to have black airmen trained in Tuskegee. They even signed a petition of protest and sent it to their senators in Washington D.C. However, the military chose to locate the training field in Tuskegee. Hastie dropped his protests to the plan in order to avoid further delay in establishing the training field. Later, Hastie resigned from his position at the War Department in 1943 because he felt that the Air Command was obviously set on continuing the pattern of segregation when it set up a separate training base for black ground personnel. It was determined that it was necessary for black pilots to have black ground crews because of the problems that would be caused if a white pilot was killed due to an airplane’s mechanical failure.

The candidates who went to Tuskegee for training had done so well on the entrance test that the white officers tested them a second time because they were convinced the blacks had found a way to cheat on the exam. These men faced great challenges because they not only had to learn how to fly; they also had to learn to assert themselves when everything else in their lives had trained them to be subservient. As the men completed their training, the 99th Squadron was born.

The air training base at Tuskegee was clearly segregated. The hated signs indicating “whites only” were clearly displayed. The white instructors made it very difficult for the pilots to succeed at their training.

It was Eleanor Roosevelt who put the training program into the spotlight when she visited the Tuskegee campus for a meeting and ended up taking a flight with Charles Anderson, one of the few black flight instructors. Later, Mrs. Roosevelt was instrumental in getting the 99th Squadron sent out from Tuskegee to participate in the war in Europe.

The pilots spent months in training followed by months spent in Africa. They saw little action until they were sent to Italy. The fact that these pilots had seen very little action meant that they were still not experienced in battle. As time went on and they continued to fly, they proved themselves as combat pilots. They were eventually combined with other black units to become the 332nd whose main job was to escort bombers. The squadron performed so well, white bomber pilots requested the 332nd when they were sent out on dangerous bombing runs. The majority of the pilots were unaware that they were being escorted by a squadron of black pilots. The 332nd became known as “the best in the business”. They were the only bomber group in history that never lost a bomber.

Figure 3 Members of the 99th U.S. Fighter Squadron

The Tuskegee Airmen fought two battles. They fought air battles over Europe and against racism in the United States. They broke barriers as they learned how to fly. Roscoe Brown, one of the airmen, said that he knew they were a part of the civil rights movement when they became U.S. Army Air Corps pilots. Another indicated they were fighting for “double victory” because they fought for their right to become pilots and fought for victory during World War II. The Tuskegee Airmen had been trained as an experiment, and the experiment was proved to have been a success.

The airmen served in order to prove their patriotism and ability, hoping to win the respect of white America. One of them said: “In spite of my status as a second class citizen which I knew existed, I loved America as much as any of its first class citizens. And, all of my life, in my family, America was the country that we were to defend if there was the need to do so.”

Using the terms “first-class” and “second-class” indicates a difference in importance and value. It is hard to imagine knowing that your life is considered far less valuable than the guy who lives down the street, whose skin just happens to be white.

After World War II ended, when the ship that carried the airmen pulled into port, it was made very clear to them that the welcome on the docks was not for them. As they disembarked, they were greeted with signs that directed white personnel to go in one direction while colored personnel were sent in another. Lee Archer of the Tuskegee Airmen said, “Nothing had changed as far as I was concerned. We left a segregated organization and when we came back, the damn thing was still there.” Another of the Airmen said: “What America so quickly forgets is the negro’s love for America. It’s his country too by damn, it doesn’t matter what you men as an individual think of me, it’s what my country means to me.”

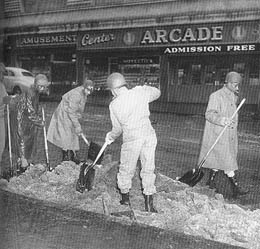

Figure 4 Troops in Tacoma

This picture is taken in Tacoma, Washington. Black troops being served milk and doughnuts by Red Cross workers. The soldiers were waiting for troop transport trains to take them to their discharge centers at the end of the War.

END OF MILITARY SEGREGATION

President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981 on July 28, 1948. This Executive Order declared there would be equality and opportunity in the United States Military. However, the Order did not automatically change the attitudes of those in positions of authority. General Omar Bradley spoke out in a news conference stating that he was in favor of continuing segregation, at least in the lower levels of military service. Interesting note about General Bradley, he was a white man, born in Missouri. One of the Tuskegee Airmen said: “The Army was desegregated, but we still had the problem of integration. I went through hell during the integration.”

Overall, desegregation in the United States Military was a fairly smooth process for the organization as a whole, because it is a self-contained institution that promotes physical and psychological separation from society at large. The military has a single Commander in Chief and when the President signs an Order, the troops obey. In the case of desegregation, this is a very good thing. That said, the desegregation of the military was not completed until after the beginning of the war in Korea.

Looking back from the perspective of the future, the segregation that has taken place in this United States for a major portion of the 20th Century is, at time, unbelievable. Were it not for the pictures and articles that had been printed, most people would prefer to think it never happened, or that it happened to a very small group of people. The “master narrative” of American history leads people to believe that segregation only involved a few southern states. This is simply not true. Segregation and the overall horrendous treatment of our black citizens are wounds we continue to deal with, whether we recognize them as such, or not. One example of the continuing wounds, or echoes, from this time period is the achievement gap between white and black students. Children who did not feel welcome at school are now parents or grandparents of children in school.

It is my hope that the discrimination and segregation of this time in history will never be repeated here in the United States or anywhere else. I hope that we are a people who can learn from the mistakes of the past so that our children and our children’s children will have a much brighter future. You might say, “I have a dream”, won’t you join me?

References

Takaki, Ronald T. Double Victory: a Multicultural History of America in World War II. Boston: Little and Brown, 2001. P. 24. Print.

NAACP.org. 2011. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. 19 February 2011. <http://www.naacp.org/content/main>

Wexler, Sanford. The Civil Rights Movement: An Eyewitness History. New York: Facts on File. 1993. P. 26. Print.

Thecrisismagazine.com. 2011. The Crisis Magazine. 19 February 2011. <http://www.thecrisismagazine.com>

http://books.google.com/books?id=LlsEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA193&dq=the+crisis+magazine+July+1940&hl=en&ei=kqpETan3O4LSsAPd9LXjCg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=bookthumbnail&resnum=4&ved=0CE0Q6wEwAw#v=onepage&q&f=false

Dalfiume, Richard M. “Military Segregation and the 1940 Presidential Election.” Phylon 30: 1969: 42-55. P. 43. Print.

“Black Pioneers at the U.S. Military Academies.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, No. 39 (Spring, 2003), pp. 12-14. Print.

Taylor, Quintard. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1994. Print.

Bowers, William T., Hammond, William M., MacGarrigle, George L. Black Soldier, White Army: the 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1996. P. 20. Print.

Allen, Robert. The Port Chicago Mutiny. New York: Warner Books, 1989. Print.

James, C. L. R., George Breitman, Ed Keemer, and Fred Stanton. Fighting Racism in World War II. New York: Monad : Distributed by Pathfinder, 1980. Print.

Irons, Peter. Jim Crow’s Children: the Broken Promise of the Brown Decision. New York: Viking, 2002. Print.

Bowers, William T., Hammond, William M., MacGarrigle, George L. Black Soldier, White Army: the 24th Infantry Regiment in Korea. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1996. P. 19. Print.

Astor, Gerald. The Right to Fight: a History of African Americans in the Military. Novato, CA: Presidio, 1998. Print.

James, Breitman, Keemer, and Stanton 48.

Johnson, Guy B. “Freedom, Equality, and Segregation.” The Review of Politics 20. 1958: 147-163. Print.

Francis, Charles E. The Tuskegee Airmen: the men who changed a nation. Boston: Branden Publishing Company, 1988. Print.

“The Tuskegee Airmen”. Dir. W. Drew Perkins and Bill Reifenberger. PBS. Paramount, 2003.

Hastie, Judge William H. “Oral History Interview.” Interview. 5 January 1972. Jerry N. Hess. 16 – 21.

“The Ninety-Ninth Squadron.” Time. 3 August 1942. Print.

Perkins and Reifenberger.

Perkins and Reifenberger.

Perkins and Reifenberger.

“Members of the 99th U.S. Fighter Squadron.” Civil Rights in the United States. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2010. Print.

Perkins and Reifenberger.

Perkins and Reifenberger.

Perkins and Reifenberger.

Photographer, City. “D21209-2 (Unique: 13378).” Tacoma Times. 1946.

“Bradley for Segregation.” Tacoma News Tribune. Tacoma, 29 July 1948. Print.

Perkins and Reifenberger.

Butler, John Sibley. “Affirmative Action in the Military.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 523 (1992): 196-206. Print.