By Kaitlyn Texley

We’ve all heard it said, without bees humanity would cease to exist four years after. Thanks to a fungus we may be approaching this apocalyptic prediction. Colony collapse is nothing new. We’ve read about it, seen it on TV and heard conspiracy theories about the multitudes of causes. Recent research into what is actually causing the rapid collapse revealed that it is actually the parasitic microsporidia Nosema ceranae. Even weirder, bees exposed to fungicides and pesticides the rates of fungal infection, or nosemosis, are even higher (Pettis, et al 2013).

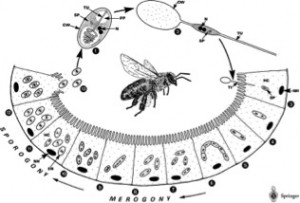

The spores of the N. Ceranae enter through the bee’s mouth and travel into the mid-gut. In bees, the mid-gut is where the digestive enzymes used to break down pollen reside. Here the microsporidia’s spores grow, reproduce and create more spores. The microsporidia feeds off of the cells within the bee’s mid gut causing damage and weakening the bee. As it does this, the microsporidia also inhibits the genes responsible for the regeneration of the intestinal tissue (Dussaubat et al, 2012). So not only is the mid gut being digested and consumed by the fungi, the bee’s body can’t heal any of the destruction.

The bee’s body responds by generating antioxidant enzymes and sending them to the site of the Nosema ceranae infection (Dussaubat et al, 2012). This seems to do little for the poor bee. The microsporidia continues to ravage the intestinal tract eventually travelling to the rectum and out with the bee’s poop. Healthy worker bees then clean up the poop and become infected by the microsporidia themselves.

The effects are really terrible. The little worker bee can have 30-50 million spores within their tiny little body (Nosema ceranae and nosema disease of honeybees, 2010). Of course this has an impact on their well-being. They become tired and are unable to produce “brood food” because of the total takeover by the fungus. This food is meant to be eaten by the baby bees, however in a severe case of Nosema ceranae infection, there may not be many babies. If the queen becomes infected her ovaries stop working and she is unable to produce eggs, and thus, babies (Nosema ceranae and nosema disease of honeybees, 2010).

How does a hive get exposed to the microsporidia? Sometimes honey-bees will rob other hives if they can’t get enough food. If they rob a hive that has honey containing Nosema ceranae spores they’re screwed (Nosema ceranae and nosema disease of honeybees, 2010). Apiaries can also increase the likelihood of infection by combining two dwindling colonies, both of which are, unbeknownst to the apiary, infested with Nosema ceranae (Nosema ceranae and nosema disease of honeybees, 2010).

The severity of the colony’s infection coincides with the seasons. During the colder spring months when the weather is sporadic, the bees are stuck inside of their hives. This is also when baby making begins, the worker bees are continually cleaning out contaminated combs for new baby bees and being exposed to the microsporidia. This is when the hive become highly infested and usually, if the infection is bad enough, when the colony itself collapses. If the colony does not collapse and they make it to summer, they are offered a new chance. The drones and worker bees (the adults affected by the fungus) leave the hive and die. The baby bees emerge microsporidia-free and the combs of the hive are cleaner as brooding has decreased. It’s a new lease on the colony’s life.

If the coming fall is wet, good conditions for microsporidia, the bees have a higher chance of contracting Nosema ceranae again. If the fall is dry, the colony may be safe from the infection for the following year.

It’s important for farmers, apiaries and scientists to learn as much as possible about Nosema ceranae so they can prevent the contraction of it. Although not all fungus are bad, Nosema ceranae is dependent on the bee’s mid-gut to reproduce and thrive. Unfortunately this is not only bad news for the little honey bee that’s infected, it’s bad news for the entire colony, and in fact the entire human population. If colonies keep collapsing, we may not only have a shortage of honey, we may have a shortage of nearly 1/3 of the planet’s food supply (Yang, 2006). That is not a small amount. In fact, that is a very large amount. You would have to say goodbye to blueberries, almonds and many other fruits, vegetables and nuts.

So although you may not care very much about Nosema ceranae and what it’s doing to a bee’s mid-gut, you will care when the repercussions of this widespread infection effect the food choices at your local grocery store. With a reduction of pesticides and fungicides the susceptibility for an infection to happen and spread will decrease (Pettis, et al, 2013). Along with knowledge of how the microsporidia spreads farmers, apiaries and scientists may be able to reduce the spread of Nosema ceranae and keep our food where it belongs, on our plates!

References:

Moisset, Beatriz, Buchmann, Stephen. Bee Basics; An Introduction to Our Native Bees. (2011). Retrieved January 28, 2014, from http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5306468.pdf

Dussaubat, Claudia et al. Gut Pathology and Responses to the Microsporidium Nosema ceranae in the Honey Bee Apis mellifera. (2012). PLOSone. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone0037017

Pettis, J., Lichtenberg,E., Andree, M., Stitzinger, J., Rose, R., vanEnglesdorp, D. (2013). Crop Pollination Exposes Honey Pees to Pesticides Which Alters Their Susceptibility to the Gut Pathogen Nosema ceranae. PLOSone. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070182

Nosema ceranae and nosema disease of honeybees. (2010). Retrieved January 26, 2014, from http://www.biosecurity.govt.nz/pests/nosema-ceranae.

Yang, Sarah. Pollinators Help One-Third of World’s Crop Production, Says New Study. (2006) UC Berkeley News. Retrieved January 28, 2014, from http://berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2006/10/25_pollinator.shtml

Photo: http://scientificbeekeeping.com/the-nosema-twins-part-1/