WORK

BY JOHN CALAMBOKIDIS

WORK

BY JOHN CALAMBOKIDIS

WORK

BY JOHN CALAMBOKIDIS

WORK

BY JOHN CALAMBOKIDIS

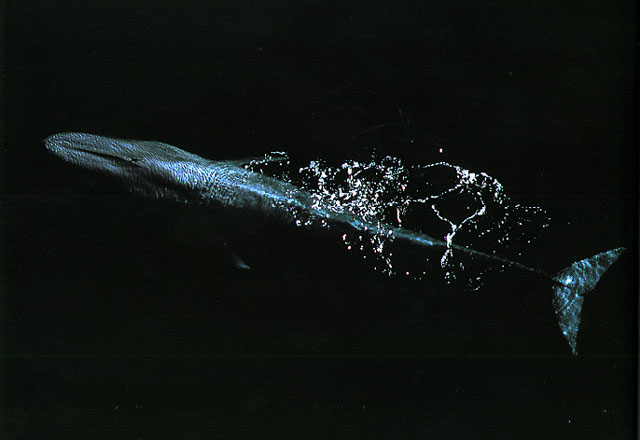

It is September and we are in a boat 30 miles (48 km) off the coast of California on a calm foggy day. The fog is dense, and I wonder how we will be able to find anything in this huge ocean. We turn the engine off and listen. At first the only sound is that of waves against the boat, then suddenly we are struck by the thunderous noise of a blue whale blowing at the surface. We head toward the noise and find the whale about a mile away. As we approach, its head breaks the surface, and we see the explosive white blow that reaches high into the air; its two blowholes are so big a toddler could crawl into them. Its light grayish-blue body is striking against the dark blue color of the sea.The broad U-shaped head disappears, and we can see only a portion of its enormous body. Its mottled back rolls through the water and rolls, and rolls, and rolls, until finally its small dorsal fin comes into view. Behind the dorsal fin the thick tail-stock is visible, capable of powering the animal to bursts of speed as high as 20 knots. On its final surfacing, this blue whale raises its huge tail-fluke out of the water before disappearing into the sea.

The sight and sound of a blue whale surfacing in the sea is still breathtaking, even after spending the last ten years studying this species. Not that long ago, it was a sight that many feared would never be experienced again. Shortly after the hunting of blue whales had ended in the mid I960s, it was thought that so few remained that extinction of this species was imminent. The first half of the twentieth century was marked by rapacious exploitation; modern whaling fleets efficiently stalked the seas and pursued and killed whales in all oceans of the world. Blue whale populations were decimated, first in the North Atlantic, then the North Pacific, and finally in Antarctic waters. The killing was so intensive that George Small, in his book, The Blue Whale, which popularized the plight of this species, concluded:

The unrestricted slaughter that followed in the southern hemisphere resulted four decades later in the virtual extinction of the biggest animal that ever lived on the face of the Earth. The few blue whales remaining there, not yet free from the threat of manšs explosive harpoons, cannot perpetuate themselves.

Fortunately, this dire prediction did not come to pass; although blue whale populations remain endangered and show little sign of recovery in most areas, there is also some cause for optimism. Blue whales in several regions are faring better than had been thought. Off the coasts of California and Mexico a surprisingly large population of blue whales has been discovered, which makes us hopeful that, although their populations are still at depressed levels, the species is no longer on the brink of extinction.

In our research, we have had the opportunity to study the California -- Mexico population, which has astonished many scientists by its size. We first stumbled upon them while studying humpback whales off central California in I986 and decided to take advantage of this opportunity to collect data on this rare species. Little did we know that they would become a primary focus of our work, and we hardly imagined that we were studying the largest remaining population of blue whales left in the world! We feel privileged to have gained new information on the biology and population structure of this species which had largely gone unstudied since the end of whaling.

Here, we would like to share our excitement and insights into what is known about blue whales and recount some of the experiences we have had studying these amazing creatures. ....