Descartes, Rules for the Direction of the Mind

http://faculty.uccb.ns.ca/philosophy/kbryson/rulesfor.htm

RULE XII

Finally, we must make use of all the aids of understanding, imagination, sense, and memory; and our aims in doing this must be, first, to gain distinct intuitive knowledge of simple propositions; secondly, to relate what we are looking for to what we already know so that we may discern the former; thirdly, to discover those truths which should be correlated with each other, so that nothing is left out that lies within the scope of human endeavor.

This Rule sums up all that has been said already, and gives a general account of the various particulars that had to be explained: as follows.

Only two things are relevant to knowledge: ourselves, the subjects of knowledge; and the objects to be known. In ourselves there are just four faculties that can be used for knowledge: understanding, imagination, sense, and memory. Only the understanding is capable of perceiving truth, but it must be aided by imagination, sense, and memory, so that we may not leave anything undone that lies within our endeavor. On the side of the object of knowledge, it is enough to consider three points: first, what is obvious on its own account; secondly, the means of knowing one thing by another; lastly, the inferences that can be made from any given thing. This enumeration seems to me to be complete, and not to leave out anything that can be attained by human endeavor.

Turning therefore to the first point <the subjective aspect of knowledge>, I should like to expound here the nature of the human mind and body, the way that the soul is the form of the body, the various cognitive faculties that exist in the whole composed <of mind and body> and their several activities; but I think I have not enough space to contain all that would have to be premised before the truth on these matters could be made clear to everybody. For it is my aim always to write in such a way that, before making any assertion on the ordinary controversial points, I give the reasons that have led me to my view and might, in my opinion, convince other people as well.

Since such an exposition is now impossible, I shall content myself with explaining as briefly as possible the way of conceiving our means of knowledge that is most useful for our purpose. You need not, if you like, believe that things are really so; but what is to stop us from following out these suppositions, if it appears that they do not do away with any facts, but only make everything much clearer ? In the same way, geometry makes certain suppositions about quantity; and although in physics we may often hold a different view as to the nature of quantity, the force of geometrical demonstrations is not in any way weaker on that account.

My first supposition, then, is that the external senses qua bodily organs may indeed be actively applied to their objects, by locomotion, but their having sensation is properly something merely passive, just like the shape (figuram) that wax gets from a seal. You must not think this expression is just an analogy; the external shape of the sentient organ must be regarded as really changed by the object, in exactly the same way as the shape of the surface of the wax is changed by the seal. This supposition must be made, not only as regards tactual sensations of shape, hardness, roughness, etc., but also as regards those of heat, cold, and so on. So also for the other senses. The first opaque part of the eye receives an image (figuram) in this way from many-colored illumination; and the first membrane of the ears, nostrils, or tongue that is impervious to the object perceived similarly derives a new shape from the sound, odor, or savor[1].

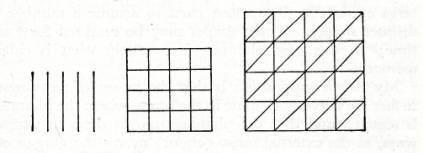

It is of great help to regard all these facts in this way; for no object of sense is more easily got than shape, which is both felt and seen. And no error can follow from our making this supposition rather than any other, as may be proved thus: The concept of shape is so common and simple that it is involved in every sensible object. For example, on any view of color it is undeniably extended and therefore has shape. Let us then beware of uselessly assuming, and rashly imagining, a new entity; let us not deny anyone else's view of color, but let us abstract from all aspects except shape, and conceive the difference between white, red, blue, etc., as being like the difference between such shapes as these:

What trouble can this lead us into ? And so generally; for assuredly the infinite multiplicity of shapes is adequate to explain all varieties of sensible objects.

My second supposition is that when the external sense <organ> is disturbed by the object, the image (figuram) it receives is transmitted to another part of the body, called the <organ of> common sensibility; this happens instantaneously,,, and no real entity travels from one organ to the other. In just the same way (I conceive) while I am now writing, at the very moment when the various letters are formed on the paper, it is not only the tip of the pen that moves; there could not be the least movement of this that was not at once communicated to the whole pen; and all these various movements are also described in the air by the top end of the pen; and yet I have not an idea that something real travels from one end of the pen to the other. For who could suppose that the parts of the human body have less interconnexion than those of the pen? and what simpler way of explaining the matter could be devised?

My third supposition is that the <organ of> common sensibility also plays the part of a seal, whereas the phantasy or imagination is the wax on which it impresses these images or ideas, which come from the external sense <organs> unadulterated and without <the transmission of> any body; and this phantasy is a genuine part of the body, large enough for its various parts to assume a number of distinct shapes. These shapes may be retained for some time; in this case phantasy is precisely what is called memory.

My fourth supposition is that the power of movement, in fact the nerves, originate in the brain, where the phantasy is seated; and that the phantasy moves them in various ways, as the external sense <organ> moves the <organ of> common sensibility, or as the whole pen is moved by its tip. This illustration also shows how it is that the phantasy can cause various movements in the nerves, although it has not images of these formed in itself, but certain other images, of which these movements are possible effects. For the pen as a whole does not move in the same way as its tip; indeed, the greater part of the pen seems to go along with an altogether different, contrary motion. This enables us to understand how the movements of all other animals are accomplished, although we suppose them to have no consciousness (rerum cognitio) but only a bodily <organ of> phantasy; and furthermore, how it is that in ourselves those operations are performed which occur without any aid of reason.

My fifth and last supposition is that the power of cognition properly so called is purely spiritual, and is just as distinct from the body as a whole as blood is from bone or a hand from an eye; and that it is a single power. Sometimes it receives images from the common sensibility at the same time as the phantasy does; sometimes it applies itself to the images preserved in memory; sometimes it forms new images, and these so occupy the imagination that often it is not able at the same time to receive ideas from the common sensibility, or to pass them on to the locomotive power in the way that the body left to itself -would. In all these processes the cognitive power is sometimes passive, sometimes active; it plays the part now of the seal, now of the wax; here, however, these expressions must be taken as merely analogical, for there is nothing quite like this among corporeal objects. The cognitive power is always one and the same; if it applies itself, along with the imagination, to the common sensibility, it is said to see, feel, etc.; if it applies itself to the imagination alone, in so far as that is already provided with various images, it is said to remember; if it does this in order to form new images, it is said to imagine or conceive; if, finally, it acts by itself, it is said to understand. (The manner of this last operation will be explained at more length in the proper place). In accordance with these diverse functions the same power is called now pure intellect, now imagination, now memory, now sense; and it is properly called mind (ingenium) when it is either forming new ideas in the phantasy or attending to those already formed. We regard it as capable of these various operations; and the distinction between these terms will have to be observed in what follows. In terms of these conceptions, the attentive reader will easily gather how we must seek to aid each faculty, and how far human endeavor can supply what is lacking to the mind[2].

For the understanding may be set in movement by the imagination, or on the other hand may set it in movement. Again the <organ of> imagination may act on the senses by means of the locomotive power, by applying them to their objects; or on the other hand they may act upon it, since it is upon it that they trace images (imagines) of bodies. Further, memory (considered, that is, as a corporeal faculty like the recollections of brutes) is nothing distinct from imagination. From this it is a certain inference that if the understanding is occupied with objects that have no corporeal or quasi-corporeal aspect, it cannot be aided by these faculties; on the contrary, we must prevent it from being hindered by them; sense must be banished, and imagination stripped (so far as possible) of every distinct impression. If, on the other hand, the understanding intends to examine something that can be referred to <the concept of> body, then we must form in the imagination as distinct an idea of this thing as we can; and in order to provide this in a more advantageous way, the actual object represented by this idea must be presented to the external senses. There are no further means of aiding the distinct intuition of individual facts. The inference of one fact from several, which often has to be carried out, requires that we should discard any element in our ideas that does not need our attention at the moment, in order to make it easier to keep the remainder in our memory; and then we must similarly present to the external senses, not the actual objects of our ideas, but rather compendious diagrams of them; so long as these are adequate to guard against a lapse of memory, the less space they take up the better. And anybody who observes all these precepts will, I think, have left nothing undone as regards the first point <the subjective conditions of knowledge>.

We must now take the second point <the conditions relating to the object of knowledge>. Here we must make a careful distinction between simple and compound notions, and try to discern, as regards each class, the possible sources of error, in order to avoid it, and the possible objects of assured knowledge, in order to occupy ourselves with these alone. Here, as previously, I shall have to make some assumptions that are perhaps not generally received; but it does not matter much, even if they are no more believed in than the imaginary circles by which astronomers describe their phenomena, so long as they enable you to distinguish the sort of apprehension of any given thing that is liable to be true or false.

In the first place, we must think differently when we regard things from the point of view of our knowledge and when we are talking about them as they are in reality. For example, take a body that has shape and extension. We shall admit that objectively there is one simple fact; we cannot call it, in this sense, ' a compound of the natures body, extension, and figure ', for these ' parts ' have never existed separate from one another. But in respect of our understanding we do call it a compound of these three natures; for we had to understand each one separately before judging that the three are found in one and the same subject. Now we are here concerned with things only in so far as they are perceived by the understanding; and so we use the term ' simple' only for realities so clearly and distinctly known that we cannot divide any of them into several realities more distinctly known, for example, shape, extension, motion, etc.; and we conceive of everything else as somehow compounded out of these. This principle must be taken quite generally, without even excepting the concepts that we sometimes form by abstraction even from simple ones. For example, we may say that figure is the terminus of an extended thing, meaning by 'terminus' something more general than 'figure', since we may also say' terminus of a duration', ' terminus of a motion', etc. But although in this case the meaning of ' terminus ' is abstracted from figure, it is not therefore to be regarded as simpler than figure; on the contrary, since it is predicated also of other things, e.g. the end of a duration or motion, which are wholly different in kind from figure, it must have been abstracted from these too, and is thus something compounded out of quite diverse natures - in fact, its various applications to these are merely equivocal.

Secondly, the things that are termed simple (in relation to our understanding) are either purely intellectual, or purely material, or common<to both realms>. The purely intellectual objects are those that the understanding knows by means of an innate light, without the help of any corporeal image. For there certainly are some such objects; no corporeal idea can be framed to show us the nature of knowledge, doubt, ignorance, or the action of the will (which we may call volition), or the like; but we really do know all these things, and quite easily at that; we need only have attained to a share of reason in order to do so. Those objects of knowledge are purely corporeal which are known to occur only in <the realm of> bodies: e.g. shape, extension, motion, etc. Finally, we must term common <to both realms> what is predicated indiscriminately now of corporeal things and now of spirits; e.g. existence, unity, duration, etc. We must also refer to this class axioms that form connecting links between other simple natures, and on whose self-evident character all conclusions of reasoning depend. For example: things that are the same as a single third thing are the same as one another; things that cannot be related in the same way to a third thing are in some respect diverse, etc. The understanding may know these common properties either by its own bare act, or by an intuition of images of material things.

Further, among these simple natures I wish to count also privations or negations of them, in so far as we conceive of such; for my intuition of nothingness, an instant, or rest is not less genuine knowledge than my concept of existence, duration, or motion. This way of regarding them will be helpful, for it enables us to say by way of summary that everything else we get to know will be a compound of these simple natures; for example, if I judge that some figure is not moving, I shall say that my thought is in a way a compound of ' figure ' and 'rest'; and so in other cases.

Thirdly, the knowledge of each of these simple natures is underived, and never contains any error. This is easily shown if we distinguish the intellectual faculty of intuitive knowledge from that of affirmative or negative judgment. For it is possible for us to think we do not know what in fact we do know; namely, we may be of opinion that besides the actual object of intuition, or what is grasped in our experience (cogitando), some further element hidden from us is involved, and this opinion (cogitatio) of ours may be false. Hence it is evident that we go wrong if we ever judge that one of these simple natures is not known to us in its entirety. For if our mind grasps the least thing to do with such a nature-as is necessary ex hypothesi if we are forming some judgment about it-this of itself entails that we know it in its entirety; otherwise it could not be termed simple, but would be compounded of the element perceived by us and the supposed unknown element.

Fourthly, the conjunction of these simple natures with one another is either necessary or contingent. It is necessary when one is implicitly contained in the concept of the other, so that we cannot distinctly conceive of either if we judge that they are separated; it is in this way that figure is conjoined with extension, motion with duration or time, etc., since an extensionless figure or a durationless motion is inconceivable. Again, if I say 'four and three are seven ' this is a necessary conjunction; for we have no distinct concept of the number seven that does not implicitly include the numbers three and four. Similarly, any demonstrated property of figures or numbers is necessarily connected with that of which it is asserted. It is not only in the sensible world that we find this sort of necessity, but we have also cases like this: from Socrates' assertion that he doubts everything there is a necessary consequence ' therefore he understands at least what he doubts ', or again ' therefore he knows that there is something that can be true or false ', or the like; for these are necessarily bound up with the nature of the doubt. A combination of natures is contingent when they are not conjoined by any inseparable relation; as when we say that a body is animated, that a man is clothed, etc. Many necessary conjunctions, moreover, are generally counted as contingent, because their real relation is generally unobserved, e.g. the proposition ' I am, therefore God is', or again, ' I understand, therefore I have a mind distinct from the body', and the like. Finally, it is to be observed that very many necessary propositions have contingent converses; e.g. although God's existence is a certain conclusion from mine, my existence cannot be asserted on account of God's existence.

Fifthly, we can never have any understanding of anything apart from these single natures and their blending or composition. It is often easier to attend to a conjunction of several than to separate out one from the others; for I may, e.g. know a triangle without ever having thought that this involves knowledge of angle, line, the number three, figure, extension, etc. But this in no way goes against our saying that the nature of a triangle is composed of all these natures, and that they are prior to ' triangle ' in the order of knowledge, since they are the very natures that are understood to occur in a triangle. Moreover, there may well be many other natures implicit in 'triangle' that escape our notice; e.g. the size of the angles (their being equal to two right angles), and an infinity of relations between the sides and the angles, the sides and the area, etc.

Sixthly, the natures called 'compound' are known to us either because we have experience (experimur) of them or because we ourselves compound them. By our experience I mean sense-perception, hearsay, and in general everything that is either brought to our understanding from outside or arises from its own self-contemplation. It must here be remarked that no experience can deceive the understanding if it confines itself to intuition of what is presented to it-of what it itself contains, or what is given by means of a brain-image-and does not go on to judge that imagination faithfully reproduces the objects of the senses, or that the senses give us true pictures (figuras) of things, in short, that external things are always what they seem. On all such matters we are liable to go wrong; e.g. if somebody tells us a tale and we believe the thing happened; if a man suffering from jaundice thinks everything is yellow because his eye is suffused with yellow; if again, there is a lesion in the organ of imagination, as in melancholia, and we judge that the disordered images it produces represent real things. But the understanding a sage (sapientis)[3] will not be misled by such things; as regards any datum of the imagination, he will indeed judge that there really is such a picture in that faculty, but he will never assert that this picture has been transmitted in its entirety and unchanged from the external object to the senses and from the senses to the phantasy, unless he has antecedently had some other means of knowing this fact. I say that an object of understanding is 'compounded by ourselves ' whenever we believe that something is involved in it that has not been directly perceived by the mind in experience. For example, the jaundiced man's conviction that what he sees is yellow is a mental state (cogitatio) compounded of the representation in his phantasy and an assumption that he makes on his own account, viz. that the yellow color appears not through a defect in the eye but because what he sees really is yellow. From this we conclude that we can be deceived only so long as the object of our belief is, in a way, of our own compounding.

Seventhly, this 'compounding' may take place in three ways; on impulse, or from conjecture, or by deduction. People compound their judgments about things 'on impulse' when their own mind leads them to believe something without their being convinced by any reasoning; they are determined to do so either by a higher power, or by their own spontaneity, or by the disposition of the phantasy; the first never misleads, the second rarely, the third almost always. But the first does not concern us here, since it is not something attainable by our technique. The following is an example of conjecture: Water, which is further from the center than earth, is also rarer; air, which comes above water, is still more rare; we conjecture that above air there is only a very pure aether, far thinner even than air. Views 'compounded' in this way are not misleading, so long as we regard them only as probable and never assert them as truth; they actually add to our stock of information.

There remains deduction-the only way of 'compounding' things so that we may be certain that the result is true. But even here all sorts of faults are possible. For example, from the fact that this region (which is full of air) contains nothing that we perceive by sight or touch or any other sense, we may conclude that it is empty, and thus wrongly conjoin the natures ' this region ' and 'vacuum'. This error occurs whenever we judge that a general and necessary conclusion can be got from a particular or contingent fact. But it lies within our powers to avoid it; we can do so by never conjoining things unless we see intuitively that their conjunction is absolutely necessary, as we do when we infer that nothing can have shape without extension because shape has a necessary connexion with extension.

From all this the first conclusion to be drawn is that we have now set forth in a distinct way, and with what seems to me to be an adequate enumeration, the truth that we were previously able to establish only confusedly and roughly; viz. that there are no ways of attaining truth open to man except self-evident intuition and necessary inference; and it is moreover clear what 'simple natures' are. . . . It is obvious, furthermore, that the scope of intuition covers all these, and knowledge of their necessary connexions; and, in sum, covers everything that is comprised precisely in the experience (experitur) of the understanding, as a content either of its own or of the phantasy. About deduction. we shall say more in the sequel. . . .

For the rest, in case anybody should miss the interconnexion of my rules, I divide all that can be known into simple propositions and problems (quaestiones). As regards simple propositions, the only rules I give are those that prepare the mind for more distinct intuition and more sagacious examination of any given objects; for such propositions must come to one spontaneously-they cannot be sought for. This was the content of my first twelve Rules, and I think that in these I have set forth all that can facilitate the use of reason. As regards problems, they consist, first, of those that are perfectly understood, even if the solution is unknown; we shall deal exclusively with these in the next twelve Rules:[4] and, secondly, of those that are not perfectly understood; these we reserve for the last twelve. We have made this division on purpose, both in order to avoid having to speak of anything that presupposes an acquaintance with what follows, and also to teach those matters first which, in our view, should be studied first in developing our mental powers. Among ' problems perfectly understood', be it observed, I count only those as regards which we see three things distinctly: first, the criteria for recognizing what we are looking for, when we come upon it; secondly, the precise premise from which to infer it; thirdly, the way to establish their interdependence-the impossibility of modifying one without the other. We must, then, be in possession of all the premises; nothing must remain to be shown except the way of finding the conclusion. This will not be a question of a single inference from a single simple premise (which, as I have said, can be performed without rules), but of a technique for deriving a single conclusion from many premises taken together without needing a greater mental capacity than for the simplest inference. These problems are for the most part abstract ones, and are almost confined to arithmetic and geometry; so novices may regard them as comparatively useless. But I urge the need of long use and practice in acquiring this technique for those who wish to attain a perfect mastery of the latter part of the Method, in which we shall treat of all these other matters.