DISPOSAL OF THE AGED

by Amanda Driffen

The depression was a massive economic catastrophe, one that we hope will never occur again. From its onset, through and since the depression the United States Government has made economic policies in the effort to thwart a reoccurrence. Before the crash of 1929, the progressives were calling for social consciousness, while their ideas seemed radical at the time, events would make them more appealing. Possibly the last class considered, by anyone, was the elderly. In 1931 a man over forty years of age could be dismissed for approaching the "dead line", he could be let go for slowing down, becoming unreliable, physically unadapted, or careless, or simply a change in process or a reduction in force could change his fortune.1

Private pension plans existed, but men over forty were discriminated against.

It would have been too costly to include a man who would potentially draw on

his benefits in the next ten years. Some European nations sponsored old age

pension funds giving the employer no reason to discriminate2; nevertheless,

it would take drastic executive measures in an attempt to end the depression

before the United States considered such welfare. Meanwhile, it seemed that

there would be no end to poverty; it reached over oceans and across years.

Men ditched their wives in the old maternal home and wandered the horizon eating

weeds, children barefoot and miserable raised themselves, and grandparents

wasted away, or some committed suicide with the intent to lighten the burden.

Families were forced out of their homes with nowhere to go except Hooverville,

while some economists suggested that only the passage of time would tell, just

wait.3 It was thought that the Depression was like other recessions and a boom

would follow, but with poverty and unemployment so wide spread, patience waned.

It was easy for a comfortable economist to make such a pitiful suggestion,

fat in his leather chair smoking a cigar, the irritating optimist.

Like the fall of Alexandria, several profits rose from the ashes of despair.

Each of them professed an economic salvation. One had all the traits of an

American legend, except that he was old. Typically, it would take a man who

had been born in a log cabin on the prairies of Illinois to assemble an idea

that would alleviate the ills of at least one fraction of the suffering population.

In 1933, a person could still taste the dust kicked up from a wagon wheel.

The echo of tincture bottles rattled in the ears. The thrill of a traveling

swindle was a memory drifting into oblivion, but the all-perfect cure persisted.

In a letter to the editor of the Long Beach Press Tele-gram, the humble country

Doctor Francis Townsend expressed his frustration with the Depression and suggested

a solution.

Whether it was the suicide of an elderly patient or the legend of seeing an

old woman dig in the trash for food, Dr. Townsend was grief stricken and he

was compelled to action. He worried that, "there would soon be no old

folks left, and no young folks would ever want to grow old."4He and his

wife were in their sixties in 1933, recently unemployed, with no source of

income, and tired of trying to think of ways to compete in a market full of

hungry, frustrated youth. He believed that while there was a surplus of workers

there was no ethically responsible method of surplus disposal (the surplus

in this case being viable work-able humans). He pointed out that war had served

in the past as a method of class disposal, but that the last war (World War

I) only increased production while it reduced consumption. In this day and

age we hesitate to consider class disposal, but previously, wars have served

as a method of population control where a large portion of one class could

be reduced; in this case, the elderly.

The forced retirement of persons over sixty years of age would eliminate the

weary class from the saturated the workforce and lighten the burden of struggling

families. With a livable pension, this same populace could revive a lifeless

economy. It would lighten the load of poor farms, aid societies, insane asylums

and prisons! To many this idea had the earmarks of a Quack delivered concoction-cure-all.

It was opportunistic for an old country doctor to demand that the government

begin paying him a pension, and oh, by the way, all the other old folks as

well. In the same year the President of the Chamber of Commerce, remarked. "The

American people have finally become convinced that the laissez-faire economy,

which worked admirably in earlier and simpler industrial life, must be replaced

by a philosophy of planned national economy."5 The conclusion of Townsend's

letter to the editor harmonizes this sentiment. He rallies the elderly by pointing

out that the Government must "assume the duty of business activity..." 6

Townsend believed that he and his wife "were too old to work, but not

too old to vote and that there were millions like them."7

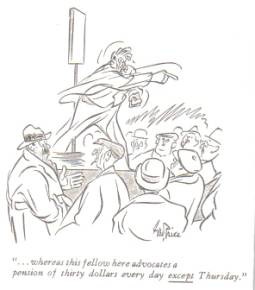

Townsend was an inspired writer. He had dabbled unsuccessfully in city politics of the old west. He was a respected doctor and surgeon, taking on a private practice in Belle Fourche, South Dakota. During the Great War, he served in the military (stateside) at the age of fifty, Dr. Townsend and his wife settled in Long Beach, California. The story of his life became legend; beginning insignificantly on the prairie, and culminating into a messianic leader of, "the most unusual mass movement of our times."8 This mass movement became more than a blue haired cane brandishing poll mob, it spurred an alliance of oldsters bent on winning the pension thereby liberating themselves and the nation from the grips of the depression. Oddly, the association took on the personality of a church or a club with the singing, the preaching, and the pledging of allegiance. Dr. Townsend bore the mantle of a pious religious leader.

Townsend admitted that he was not an economist. According to Neuberger and

Loe in An Army of the Aged, he practically invented a new arithmetic and, economics

was no longer a science; it was a hokum. Nevertheless, the old age movement

was not the only brilliant fix for the national crisis. Others like Huey Long

and Upton Sinclair rose to the podium and addressed eager audiences. The depression

produced a population that was easily charmed. Carrots seemed to be dangling

everywhere. Meanwhile, the President was back at the white house preparing

to unveil his own Pension plan.

From Roosevelt's speech before the 1932 Democratic National Convention, the

words New Deal raced across the pages and rang in the ears of the nation. Roosevelt

believed that economic laws were not made by nature, but by human beings. He

pledged the democrats present at the convention and himself to this New Deal.

He rallied the nation in his call to arms to restore America to its own people.

In his next famous speech, the inaugural address, Roosevelt promised to address

the nation with candor. From this, we get the famous expression, "The

only thing we have to fear is fear itself."9 In order to restore the nation

to its previous status, Roosevelt declared that the primary task was to put

people to work. He closed the speech by saying that the American people have

not failed, but that they made him the instrument of their wishes.

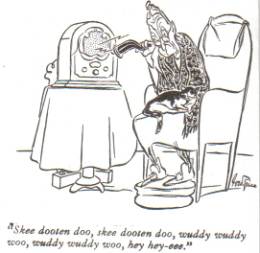

The new president's popularity solidified when he began reforms before the

inaugural dinner was cleared from the table. Within an eight-day week, the

President addressed the nation in his first Fireside Chat. Without sounding

condescending, Roosevelt used the radio to talk to the people, and to explain

his actions. This soothed an inconvenienced populous, thereby endearing the

new President and restoring confidence. In his second Fireside Chat, Roosevelt

introduced new economic policies. First, he offered employment to one-quarter

of a million unemployed, creating the Civilian Conservation Corps. Second,

he proposed putting to work government owned properties. Next, he asked congress

to pass legislation to ease mortgage distress, granted a half a billion dollars

to help with immediate relief, and authorized the sale of beer in such states

as desired it. He had said that only a foolish optimist could deny the dark

realities of the moment.

Roosevelt's reforms and policies were similar to the idea expressed in Townsend's

letter to the Long Beach Tele-gram, except that they were intended for young

men with dependents. The general idea was to wake up the economy. By supplying

a class within the population with capital, industry would be motivated to

produce. If thirteen million people were unemployed, hiring one-quarter of

a million would seem like an insult, however small; this turned the crank on

the economy. By putting men to work first, Roosevelt could provide relief for

others later. Townsend was concerned with generating a similar scenario where

one class (people over sixty) would have a disposable income of two-hundred

dollars that they would be required to spend in thirty days. He believed that

this would be enough to jump start the economy in two ways; first, old age

pensioners would be removed from the work force allowing more youths to enter

it, and second, by forcing the pensioners to spend their income, the income

would generate business that had previously come to a halt. The method that

Townsend suggested to support his plan revealed his lack of economic understanding.

It was not obvious to Townsend that "'purchasing power" does no more

than to exploit one class at the expense of another, unless it is accompanied

by an increase in goods,"10 He realized that the funds for the pension

could not have come out of thin air, but his proposed tax to support his idea

was thin air.

Before the fallacy was realized, the Townsend plan became an overnight sensation.

When the humble doctor realized how popular his idea was, he developed a petition.

It was not hard to gather signatures. Old people were more than willing to

walk door to door to gather them. Spread at first by word of mouth, the Doctor's

idea became a movement. Soon, money became available in order to spread the

idea by leaflet. The demand for the leaflets allowed for the .25-cent charge

that by depression standards was ridiculous, but they could not be printed

fast enough. Townsend clubs formed in several cities, especially in the west.

Old people gathered for the cause; and while it resembled church, it gave them

a sense of hope that church could not fulfill. Approximately 30, 000 oldsters

formed eighty clubs in San Diego alone.11 Economic pressure on merchants rose

with the movements numbers. Some merchants hung a picture of Dr. Townsend in

the window to show solidarity with the aged. Ironically, some people tried

to shop with credit in the belief that the first payment was just around the

bend. Suggested budgets distributed all over San Diego fueled the expectations

and swelled the movement's fervor.12 One would think that the movement would

go no further than the walls of the clubhouse, but it had to be taken seriously,

by 1935 Townsend announced that he had a petition bearing twenty-five million

names.13

Will Rogers wrote before his death in a plane crash, "See by the papers

Mr. Townsend appeared before the Senate committee and they had a lot of fun

and laughter at his plan. Well, they can have some fun with the amount, but

they can't have much fun with the idea of paying a pension... Now Townsend

may have to take only 25 percent or 15 percent of his original idea, but the

Senators are not going to laugh themselves out of paying old age pension."14

It was clear that President Roosevelt's New Deal would not neglect the aged.

In his second annual message to congress on January 4, 1935 Roosevelt included, "security

against the major hazards and vicissitudes of life"15 as one of three

factors he pressed on congress, included recommendations for unemployment insurance,

old-age insurance, and benefits for children, mothers and the handicapped.

In two years, over two billion dollars had been spent on the destitute; even

so, Roosevelt insisted that to dole out relief was to administer a narcotic,

a subtle destroyer of the human spirit. Later that same month Roosevelt would

submit a report to congress made by the Committee on Economic Security.

It may have seemed like a response to the Townsend plan, however, it is fabled

that the committee was formed before Townsend became a national figure.16 Furthermore,

the social security act would not cover every American over the age of sixty,

and the coverage it did offer was painfully insignificant in comparison to

two hundred dollars. Initially, when the plan was enforced, a one-time payment

was made to the elders who were expected to expire first. Roosevelt intended

that workers would pay into the social security

fund because, "With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever

scrap my social security program."17

At the passage of the Social Security Act, the Townsend movement actually reached

its peak in membership. According to Leuchtenburg, the inadequacy of the New

Deal pension system left millions of elderly Americans unprotected.18 Politicians

in support of the Townsend plan saw some success in 1935; however, the movement

crested when the former national publicity director leveled charges of corruption

at Dr. Townsend and his partner Robert Clements.19 This indicated the end of

the movement.

Roosevelt and Townsend had one thing in common. Both admitted to inadequacies

in understanding economics, and both were politicians. In Roosevelt's eighth

annual address to congress on January 6, 1941, he listed the basic things we

expected of our political and economic systems. Among the list were security

for those who need it; improvements in social economy; and to bring more citizens

under the coverage of old-age pensions. In this same speech, Roosevelt listed

four essential human freedoms, among them the third was freedom from want -

which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will

secure every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants - everywhere

in the world.20

Overton H. Taylor claimed that the New Deal was the death knell for laissez-faire

economics, once the ideal of American economy. The ideal, he said, was ethically

and economically tenable: not only would the government let business alone,

but individuals, groups or classes would let one another alone. Each would

keep their hands off of wealth belonging to others. "The weakness was

not in the ideal such but in the program of measures for its attainment."21

Taylor continues, "Economic science is the science of situations and activities

involved in the effort of society and its members to achieve economy, or efficiency,

in the use of material resources and of labor to increase wealth, or the supply

of means of satisfying wants; and all that has to do not with this quest for

efficiency, but with the struggle for power and advantage over others in the

distribution of its fruits, is of the nature of political activities, realistically

conceived as much by Machiavelli and Hobbes, and belongs in the domain of political

science."22

Theodore Roosevelt offered the Square Deal in 1904. Franklin Roosevelt died

before the New Deal became the Fair Deal proposed by his successor, Harry Truman.

It comes as a surprise that social security reform in the present day is not

labeled the Good Deal (Raw Deal has been taken). Gary DeMar writing for American

Vision calls social security the greatest chain letter, "Those paying

now are paying those receiving benefits now.23 It works like a pyramid scheme.

In 1950 there were sixteen workers paying into the system for every recipient.

Today there are 3.3 workers per beneficiary. President George Bush insists

that this is a crisis, but fails to place the Fair Deal between the 16 and

the 3.3 workers when in 1950 Social Security was extended to ten million more

people. In a nutshell, Bush wants Americans born after 1950 to put payroll

taxes into personal accounts. The benefit of this idea is that the money would

be available to a successor after death. The detriment of this idea is that

it is not suited for low income earners and the accounts would not be protected

from market swings until just before retirement. In a letter to the President

Julian Bond, Chairman of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored

People, and Kim Gandy, President of National Organization for Women, urge him

to stop his assault on the nation's most successful family and anti-poverty

program. Privatization would create a "separate but equal" system

forcing African American seniors and elderly women into poverty.24

It is unbecoming of a republican to consider pay discrimination, or a woman's

conscientious responsibility to take unpaid family leave. Privatization of

the social security system will not compensate for time lost or provide inflation

proofing or lifetime benefits. It will fail to provide for people who earn

less than 80,000 per year. The time is ripe for a Doc Townsend to rise to the

task of reforming Social Security in a realistic manner. Since the great depression,

we have come a long way; workers are encouraged to continue beyond the dead

line. While we are looking for prophets to rise up to rescue us, we should

look for a truly eloquent President who is progressively concerned with the

real people who truly depend on the economic machine.

1 Stuart Chase. The Nemesis of American Business 1931The MacMillan Company,

New York pp.132-133

2 Stuart Chase. The Nemesis of American Business 1931The MacMillan Company,

New York p. 140

3 Theodore Rosenof. Economics in the Long Run 1997The University of North Carolina

Press, Chapel Hill & London p.47

4 Dr. Francis Townsend,. New Horizons 1943 J.L. Stewart publishing Company,

Chicago Illinois

5 H. LaRue Frain, Ph.D. An Introduction to Economics 1937 the Riverside Press,

Cambridge Massachusetts p. 13

6 Dr. Francis Townsend. New Horizons 1943 J.L. Stewart publishing Company,

Chicago Illinois p.138

7 Dr. Francis Townsend. New Horizons 1943 J.L. Stewart publishing Company,

Chicago Illinois p.137

8 Richard Lewis Neuberger and Kelley Loe. An Army of the Aged 1936 the Caxton

Printers, Ltd. Caldwell, Idaho preface

9 Franklin D. Roosevelt. The EssentialFranklin Delano Roosevelt:F.D.R.'s Greatest

Speeches, Fireside Chats, Messages, and Proclamations 1995Random House, New

York pp. 27,30,51,52

10 Edward Chamberlin. Purchasing Power; from, The Economics of the Recovery

Program 1971 Da Capo Press, New York p.24

11 Richard Neuberger and Kelley Loe. An Army of the Aged 1936 the Caxton Printers,

Ltd. Caldwell Idaho p.67

12 Richard Neuberger and Kelley Loe. An Army of the Aged 1936 the Caxton Printers,

Ltd. Caldwell Idaho see pages 72 and 73 for budget proposals.

13Richard Neuberger and Kelley Loe. An Army of the Aged 1936 the Caxton Printers,

Ltd. Caldwell Idaho p. 80

14 Richard Neuberger and Kelley Loe. An Army of the Aged 1936 the Caxton Printers,

Ltd. Caldwell Idaho p.137

15 Franklin D. Roosevelt. The EssentialFranklin Delano Roosevelt:F.D.R.'s Greatest

Speeches, Fireside Chats, Messages, and Proclamations 1995Random House, New

York pp. 83-86

16 Alonzo Hamby. For the Survival of Democracy 2004 Free Press New York p 273

17 Alonzo Hamby. For the Survival of Democracy 2004 Free Press New York p 274

18 William Leuchtenburg. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal 1963 Harper & Row,

Publishers, New York p.180

19 William Leuchtenburg. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal 1963 Harper & Row,

Publishers, New York p.181

20 Franklin D. Roosevelt. The EssentialFranklin Delano Roosevelt:F.D.R.'s Greatest

Speeches, Fireside Chats, Messages, and Proclamations 1995Random House, New

York pp.200-201

21 Overton H. Taylor. The Economics of the Recovery Program 1971 Da Capo Press

New York pp.175-176

22 Overton H. Taylor. The Economics of the Recovery Program 1971 Da Capo Press

New York pp.179-180

23 Gary DeMar. "Social Security:the World's Largest (Legal) Chain Letter.

Americanvision.org 2007 Powder Springs, Ga. 3/11/07

24 Julian Bond & Kim Gandy "Letter from NOW and NAACP to George W.

Bush regarding a "separate but equal" privatized social security

system." National Organization for Women. 1995-2007 3/11/07 http://www.now.org