8

THE ICON AND THE ENIGMA: MOOD-SWINGS TOWARDS HOPE

by Amber Royster

"Senator, you're no Jack Kennedy," remarked Senator Lloyd Bentsen as prolonged shouts and applause echoed through the auditorium. It was the 1988 Vice-presidential debate, and Senator Dan Qualye had made the mistake of comparing himself to one of the most beloved presidents in American history.1 This remark has since become a part of the political lexicon as a way to deflate politicians or other individuals who think too highly of themselves. Four years later in his campaign movies, Bill Clinton used a clip of himself as a student shaking hands with President Kennedy in the Rose Garden. It is said that President Clinton even tried to style his hair in the same manner as President Kennedy.2 After all, John F. Kennedy is one of the most heralded American icons in the world today. "Where were you when Kennedy was shot" is the oft-repeated question about America in the 1960's. But after the summer of 1968, one could arguably answer: "which Kennedy?" Following closely in JFK's footsteps was his younger brother, Robert, who also achieved heroic status, but for reasons different than the elder Kennedy. As politicians they were ambiguous at best, struggling to achieve aims, keep promises, and be consistent. How did Jack and Bobby find their unique way into the hearts and minds of Americans? Was it Jack's good looks, their family name, or their untimely deaths that propelled them to mythic heights? Or could it be the speculation and story of what these men could have been that Americans subconsciously substituted for reality? From the glamour of Camelot to nationally televised assassinations, the Kennedy brothers' tragic heroism evolved in the American consciousness as supremely idealistic and vague recollections; sometimes to the complete denial of their reality. So why the ongoing love affair with these men of myth? Furthermore, which assassination, if either, might have had the greater impact on American society?

In order to understand the reasons for loving the Kennedy brothers, they must

be seen from both a politically and socially historic approach. Arthur Schlesinger,

Jr., a well-known Kennedy family biographer, ascribes to the "great man-great

achievements" point of view, attributing their fame to political savvy

and success. More recent historians and biographers give the media and the

advancement of technology the credit, asserting that the Kennedy notoriety

came with being politicians in the new age of television. But ask the ordinary

American and they will simply attribute the Kennedy's place in the culture

to the connection they had with the people; it was "a feeling of humor,

romance, idealism, and youthful energy, and a sense of hope that touched virtually

every American alive during that time." There was this feeling: "the

rise of a new generation of Americans..."3

While exploring the origins and the evolutions of the Kennedy myths is essential,

a more intuitive question is do we still need these myths and why have they

recently surfaced? Some would say we need the liberal politics of the Kennedy's,

others that we need the young idealistic personalities of political leaders

who have not yet succumbed to a corruptive sense of power. But both of these

notions are rooted in inaccurate assumptions, supporting the idea that maybe

it comes down to our need to feel a sense of hope. Thus, while one is undeniably

an icon and the other arguably an enigma, the Kennedy brothers unquestionably

lighted a broad path of such hope. On November 22, 1963, this sense of hope

began to fade.

"Brightness Falls from the Sky"

A poll conducted

by the National Opinion Research Center, an affiliate of the University of

Chicago, reported that 53% of Americans wept when they heard that President

Kennedy was assassinated.4 For almost a year following his death, expressions

of grief from national and foreign contributors poured into newspapers; in

Berlin, Germany, theaters abruptly ended their performances with one actor

saying, "We are too moved to go on."5

The Sacramento Bee lamented that a piece of America died with President Kennedy.6

The very day of his

assassination it was proposed that President Kennedy be posthumously awarded

the Medal of Honor; less than a month later, President Johnson asked Congress

to approve a 50-cent coin bearing the likeness of John F. Kennedy; and within

six months, there were streets, bridges, schools, theaters, an airport, and

a space center all bearing his name-several of which were in foreign countries

such as "Kennedy Avenue" in Teheran, Iran.7 Was this sudden memorializing

justified, or was a nation swept up in the romanticism of the brutally assassinated

image of youth, glamour, and progress? Revisionist historians were the first

to both question and lower the idealistic heights to which Kennedy's political

significance had posthumously ascended.

8

Debunking the Myth

William Leuchtenburg,

a prominent historian and commentator on the Kennedy legacy, writes about

the twentieth anniversary of President Kennedy's death: "historians

are far from reaching a consensus on President Kennedy, but few would be disposed

to rank him so highly."9 This is due in no small part to the Kennedy family

scandals and exposure of JFK's less than noble private life that followed for

years after his death, tarnishing his image and raising skepticism regarding

his presidential career. But much of the lack of acclaim from the "new

revisionists" is rooted deeply in the evaluation of Kennedy's achievements

as President. Herbert S. Parmet observed, "Kennedy was less an architect

of the future than a player at the leading edge of change...Nevertheless...the

harshest critics have conceded the place of inspiration as his chief legacy."10

This opinion of Kennedy as a figurative rather than literal champion of change

runs rampant in the commentaries. There was no notable social and economic

transformation during Kennedy's years as President; however, "the Jim

Crow that lived on until the 1960's belong[ed] to the past."11 Yes, JFK

was responsible for sending two Civil Rights Bills to Congress, but it was

in his memory that President Johnson (who had a poor record on civil rights

issues) drove the bill to fruition. JFK's stance toward foreign policy and

defense would come as a shock to believers in the mythic president. His "flexible

response," a move away from "massive response," depended nevertheless

on "the notion that the United States should have the capability of meeting

potential threats to world stability by conventional as well as [emphasis added]

nuclear means."12 In other words, the U.S. needed more nuclear weapons

in order to support world stability. Furthermore, his complex and ambiguous

policy in Vietnam (which according to Thomas Brown is the aspect of Kennedy's

career that has been "subjected to the greatest number of revisions")

was considered even by Schlesinger to be his great failure in foreign relations.13

Although not a comprehensive assessment by any means, the issues of Civil Rights,

nuclear arms, and Vietnam are nonetheless three significant issues from which

Kennedy apologists should at least reconsider their arguments when categorizing

Kennedy as "successful" in his political record. It is safe to say

that his career as President was less about solid politics and more about fluid

appearances; there was a strong foundation laid throughout Kennedy's political

career which he used to enhance his image. Youth, rhetoric, good looks, movie

star quality press conferences, and picture perfect First Family aside, John

F. Kennedy had the latest secret to political stardom: the media.

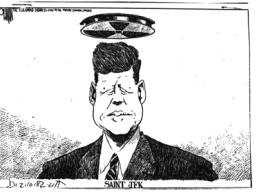

JFK with film reel over his head14

A Star Is Born

According to John

Hellman, modern societies shape or even produce a mythology "by

institutions and technologies of communication."15 Furthermore, it's not

just the media itself that participates in the formation of modern myth, but

the key myth shapers are people holding positions of power and influence within

the mass media. Elites "select, design, and promote the products presented

to the public as information or entertainment...the interests and desires of

these groups [being] crucial in determining the representations...sent out

to the public."16 The Kennedy family in their elitist status, specifically

John, displayed a keen sense of image control throughout his political career.

For instance, in order to maintain a thorough watchful eye over what the press

was writing about him, he enrolled in a speed reading course, after which he

was able to read at a rate of 1200 words per minute. Being photographed was

no different; Kennedy refused to wear hats because it made him look older,

and despite his severely painful back, he refused to be seen using walking

aids.17

Even his name became an issue in the press; on January 5, 1961, the New York

Times printed an article with the title "Kennedy Prefers 'J.F.K' To 'Jack'

for Headlines."18 "Jack" sounded young and naïve in his

opinion, and being fully aware of the increasing impact of the print media

on the American public, JFK was determined to make the news more favorable

to him.19 But his most available and viable media tool was television, due

in part to his timely arrival on the presidential scene-an ascension that paralleled

a consumer shift from Hollywood film to the immediacy and convenience of a

home television screen. Complemented by the full color

"Kennedy

in glasses, rarely worn for the camera"20

constructions of "reality" in large format weekly magazines that also had broad circulations, President Kennedy had little trouble advertising his star quality looks, compelling persona, and creative intelligence. As Joseph Berry discusses in his biography of Kennedy and the media, understanding television was another Kennedy forte. Characterized as a "cool character on a cool medium" (television), Kennedy used his oratory gifts and confidence to woo audiences. This was most apparent during the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debates, when the tanned, healthy, and well-dressed Kennedy was starkly contrasted with a sickly-looking Nixon who wore a suit that blended into the background. To say the least, Kennedy won the battle of appearances and images. However, the majority of post-debate surveys showed that (based solely on political views and arguments) a clear winner was indefinite in each of the debates.21

President Kennedy's subtle management of print media and smooth navigation

through the new frontier of television solidified his image as young, energetic,

accessible, intelligent, and capable leader of the free world. But as Kennedy's

arrival on the presidential scene coincided with the rise of the age of television,

so the stage was set for what Thomas Doherty calls "the most moving and

historic passage in broadcasting history": the assassination and funeral

of John F. Kennedy.

"Don't let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment, that was known as Camelot."

Thomas Brown makes an astute observation about the memory of JFK: "It is the day of Kennedy's death, not that of his birth, that is annually observed as a benchmark in American history." The murder of President Kennedy was a nationally televised violent disruption of American life; and considering the catastrophic decade that followed, it is no wonder that his assassination signaled "a national end of innocence, separating an era of optimism and self-confidence from one of pessimism and self-doubt." Furthermore, the relationship that Kennedy had developed with the American public via the media gave his death a very personal perspective. JFK the President wasn't assassinated-it was the man, the husband, the father, the friend, the face who spoke directly to you through the television screen who had been killed in broad daylight. The death of President Kennedy "was felt as a personal loss by millions of Americans..."22 It was the grand, public, and televised funeral that guaranteed the glorified remembrance of JFK; as the caisson passed with the Riderless Horse in tow, Americans said goodbye to their slain hero, their knight in shining armor.23

JFK's transformation into a myth happened quite literally and quickly after

his death. His life and family as "Camelot" was not an idea coined

by the media, but rather by JFK himself. In her epitaph at her husband's funeral,

Jackie reminisced of their intimate moments, listening to the soundtrack of

the Broadway musical. Jack had loved the lines about the kingdom of Arthur

and the Knights of the Round Table. There would never be "another Camelot," she

said. This evocation, according to John Hellman, would be "the first attempt

to transcend the apparent meaninglessness of John Kennedy's death...[beginning]

a process that has haunted the public consciousness of Americans through the

final third of the twentieth century [and into] the twenty first."24 The

process of coming to terms with Kennedy's death would be and is most prevalent

in narrative, a poignant element of the Kennedy obsession.

Healing Words

In the wake of Kennedy's death, writers motivated by the rising mythic status

of Kennedy began to publish biographies, memoirs, conspiracy theories, and

exposés. These attempts to preserve, explain, and even debunk the image

so loved and admired were the essence of what became the Kennedy myth. Two

of three post-assassination phenomena outlined by Hellman occurred within this

literary arena: "demonology, the search for the principle of evil that

slew the hero; and blasphemy, the denial that this incarnation of the ideal

was what it is purported to have been." These attempts to complete the

Kennedy story are still prevalent in the literary world today, not to mention

the plethora of websites that are

25

25

devoted to finding and exposing the conspiracy behind the assassination

of JFK. Similarly, historians continue to comb the life of Kennedy, seeking

evidence to prove that JFK was not all he is thought to be. But would his image

change with these revelations? If it does not, then could it be that for the

generations in 1963, he was the hope, the new found faith in democracy, the

light at the end of the tunnel? The following is an excerpt from an article

published in the November 1964 issue of Redbook:

I spoke of Kennedy as being comparable to the artist in the enlargement he gave to life. He was also like the artist in the way he used the old to create the new. This is what we wait for always, but today our need is particularly sharp and deep-reaching-the painter, the poet, the novelist, who will make the bridge between history and the future and thus dispel our isolation in the present. That, in our time, it was not an artist but a political figure who performed this act of grace is more than a surprise; it is a miracle. And it indeed makes his death an enduring occasion for mourning: it is ourselves we grieve for. 26

The third phenomenon occurred following the death of President Kennedy was known as resurrection: the return of the hero from the grave.27 America's first attempt was the 1968 presidential campaign of Robert F. Kennedy.

The Man Nobody Knew

A group of Peace Corps volunteers heard the news of President Kennedy's assassination while stationed in the Andes of Peru. "Well," somebody said, into the somber silence, "now Bobby will have to run."28 While JFK embodied an imagined fairy tale of Camelot, Robert Kennedy was the tragic prince, the redeemer, reigniting hopes and shaping the idea of what, once again, could be. Much like his older brother, Robert's allure lies in what he would have been, what he would have done.29 He didn't have movie star looks, sharp oratory skills, or the type of demeanor that could put an entire audience under his spell; he was often characterized as Jack's polar opposite - intense, moralistic, and ominous. Bobby's father, Joseph Kennedy, Sr., once boasted, "Bobby's like me...He's a hater."30

Politically speaking, Bobby struggled to find his grasp between realism and

idealism,31 or perhaps between his own identity and that of his brother. This

contradiction was certainly a core reason for Bobby Kennedy being one of the

most loved, but also one of the most hated Americans of his time.

He was an ardent prosecutor who abused the law, a champion of black pride

who allowed the FBI to torment Martin Luther King, a tardy critic of the Vietnam

War who organized U.S.-sponsored assassination operations in the Third World,

a fearless rebel who would not take on an unpopular president until another

man cleared the way.32

"The Bobby Twins"33

Yet this contradiction is also what makes Bobby contemporary and so appealing to an uncertain age. Bobby was the man nobody knew, making him less of an icon like John and more of an enigma.

An Apostle of Involvement

What people did know about Bobby Kennedy was that he appeared to be a "tribune of the underclass"34 in American society. The African-American community seemed particularly drawn to Bobby, as he was able to connect to their suffering, sorrow, and anger through the death of his brother (the shock of which, as asserted by Ronald Steel, triggered a transformation in Robert from vindictive "Brother Protector" to "sensitive pastor to life's victims"). Robert became the inheritor of his brother's Lincoln-like legacy-the Great Emancipator who had died for the cause of Blacks. But unlike his brother, Bobby was active in the struggle for Black equality, an "apostle of involvement"35 against alienation. He did not merely talk about the horrible conditions in the ghettos, but he planned education, training, and employment programs for those trapped in them.36 In a speech given at the University of Alabama, Robert Kennedy asserted this image as a champion for racial and ethnic minorities:

History has placed us all, Northerner and Southerner, black and white, within a common border and under a common law. All of us, from the wealthiest and most powerful of men to the weakest and hungriest of children, share one precious possession: the name "American." 37

Bobby's compassion was also extended to the poor, as he described "the other America" in a speech given at the University of Kansas:

I have seen these other Americans-I have seen children in Mississippi starving, their bodies so crippled by hunger: and their minds have been destroyed for their whole life that they will have no future. I have seen children in Mississippi-here in the United States, with a gross national product of eight hundred billion dollars...

But even if we act to erase material poverty, there is another great task. It is to confront the poverty of satisfaction-a lack of purpose and dignity-that inflicts us all. Too much and too long, we seem to have surrendered community excellence and community values in the mere accumulation of material things.38

Examining the

dynamic of the Kennedy family, it is easy to comprehend Bobby's empathy towards

these groups of Americans. Lost in the shadow of his brother, identified

as the runt of the litter, and virtually ignored by his domineering father,

Bobby understood what it meant to be an outsider.39 Jack Newfield, a Kennedy

biographer who traveled with him on the campaign trail once remarked, "Kennedy

had the almost literary ability to put himself inside other people, to see

the world with the eyes of its casualties."40 Bobby had at one time been

a casualty himself, and the empathy he evoked was during a time of great social

crisis in America. That his ideals remained untested and unfulfilled made it

even more possible to believe that Bobby would have succeeded.

No Excuses

Not only did Robert Kennedy appeal to the growing number of disadvantaged Americans, but he also was a campaigner (albeit overdue) for peace. His late blooming into the anti-Vietnam movement, however, was easily overlooked as he openly admitted his participation and responsibility in the escalation of the war. "I was involved in many of the early decisions of Vietnam," he said in a March 1968 speech, "decisions which helped set us on our present path...I am willing to bear my share of the responsibility, before history and before my fellow-citizens. But past error is no excuse for its own perpetuation..."41 Bobby had the vantage point of five more years in Vietnam, during which America had managed to isolate itself through unilateralism, but he still held dear the virtues exhibited by his brother during the Cuban Missile Crisis and the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty; "the art of peace," Bobby called it, and "decent respect for the opinions of mankind." He even encouraged the recognition of Southeast Asian nations as "individual entities with their own welfare and independence..."42 But once again Americans found themselves victim to the future conditional, convinced that if Bobby had lived and become president, he would have quickly ended the Vietnam War. Instead, "the last major leader who allowed us to at least imagine we could realize the ideals of American politics"43 was killed, and another seven years of war in Vietnam ensued.

Open Wounds

The myth-making of Robert Kennedy following his assassination happened in similar fashion to his brother: literally and quickly. Newspapers printed stories and editorials almost daily from the day of his death to its first anniversary. "[Bobby's assassination] removed forever one of the most promising young political leaders in recent American history..." wrote Tom Wicker on June 6, 1968.44 One year later, two days before the anniversary of Bobby's death, the same tune was being sung: "On Thursday morning it will be a year since Robert Kennedy was shot. Time has not diminished the sense that life without him is incomplete."45 Even as recently as 2006 a movie was made about the day Bobby was killed, depicting the loss of hope felt

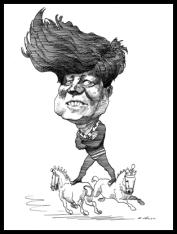

Robert Kennedy caricature 46

by a nation over the slaying of another knight of Camelot. "The yearning

for Robert Kennedy-or somebody like him," a reporter wrote thoughtfully

twenty-four years after his death, "is an open wound in some parts of

America."47 Certainly the death of Robert Kennedy had a much more significant

impact than that of his brother-it was the final nail in the coffin of hope,

peace, and the possibility of a nation undivided by race, ethnicity, or class.

Robert Kennedy offered more than just the style and rhetoric to which his brother

has since been reduced; he embodied the myth of Camelot, demonstrating more

substance than style, more heart than grace.48 Yes, it is possible that Bobby

would never have achieved his great aims; but the possibility of failure is

a mere shadow behind the devastation of stolen opportunity.

The Once and Future King

There continues to be speculation about the intentions of Robert Kennedy as

a friend to minorities. Some historians insist that it was pure politicking

at the heart of his empathy campaign, knowing that he would need to secure

the votes of the communities he valiantly tried to save. Others give the credit

to his older brother John, because of whom Robert was given a large amount

of slack for his contradictions and inconsistencies.49 But regardless of the

legitimacy of these accusations, none can deny that Bobby Kennedy succeeded

in inspiring a nation, bringing all people hope, and striving for more than

the status quo. He not only began to live up to the hopes Americans had for

him, but also to the hopes they had for his brother. Accordingly, is Robert

the rightful heir to the Kennedy throne?

50

Does the Truth Matter?

The exploration of the Kennedy myths has little to do with proving them to be true or false. In fact, the validity of the myths matters least; the questions of why these myths exist and what purpose they serve are most important, as the answers determine their future strength within American culture. Quite simply, the myths exist because we need the image of a hero the hope of a new hero to emerge. Once again America finds itself existing in a world characterized by feelings of alienation and isolation; the relationship we have with our political and economic institutions is one of being at an infinite distance from a foreign world that seems to run our lives like a puppet master with its dolls. The myths of John and Robert Kennedy are the tragic story of America's savior-knights who had the ability to transcend the fragmented social world and build a community of connectedness and ethical purpose. 51 Given the current climate of American society, politics, and economy, there has never been a better time for a revival of the Kennedy myths, and this was demonstrated by the release of the film "Bobby" in 2006, as well as several literary works that relate the politics of the Kennedys to those of present day. "The Gospel According to RFK: Why It Matters Now," does just that:

In 2004, another election year, when many Democrats and many other Americans feel that we are living under a counterfeit flag after the dubious, even stolen, election of 2000, living even in a coup situation, it is important to tell the story of RFK's campaign...he laid out a vision for America and the world that rings true today...end the war; decrease the gap between rich and poor; honor the importance of dissent especially in time of war; repair the damage done to our relations with European allies because of the war; create a new politics of greater participation, engaging young people in the process for change; build successful communities in poor and more...52

Each of these points can be found in Robert Kennedy's 1968 presidential campaign speech repertoire. It's shocking to realize that what America needs today are the ideals and leadership from almost forty years ago. What a shame that the

53

majority of American progress in the last forty years has been in the escalating

gross national product and our obsession with materialism. Isn't that what

Bobby campaigned against?

Evoking the Myth, Reviving Hope

Our time is one without heroes in the midst of a steady deterioration of hope. As the dawn of another presidential election rises, Americans once again will search for the one who can save the nation, or at the very least spark the possibility of salvation. Forty years ago, Robert Kennedy personified this mood of a similar turbulent time in our history. The question is did the mood survive the generations who experienced it?54 Still, whether their greatness was perceived or authentic, both John and Robert Kennedy will continue to be the litmus for American leaders, as they have been ever since their deaths. But even if a hero is not soon found, there will still be the myths of Jack and Bobby on which to pin our hopes.

1 The Bentsen-Quayle Vice Presidential Debate. 5 October 1988. Commission on

Presidential Debates. 4 Mar. 2007 <http://www.debates.org/pages/trans88c.html>.

2 Mark Lawson. "Still Crazy About JFK." The Guardian (UK) 15 Nov.

2003: 23.

3 Peter Gabel. "The Spiritual Truth of 'JFK'." Tikkun Mar-Apr 1992.

4 "Most of U.S. Wept at Assassination." New York Times 7 Mar. 1964:

11.

5 "Opinion of the Week: At Home and Abroad." New York Times 23 Nov.

1963: 8.

6 Ibid.

7 The New York Times carried numerous articles throughout the months following

the assassination of John F. Kennedy, outlining the various memorials dedicated

to him. See bibliography for specific references.

8 George Christian. "The Kennedy Charisma." Houston Chronicle 9

Oct. 1983: 20.

9 William E. Leuchtenburg. "John F. Kennedy, Twenty Years Later." American

Heritage 35.1 (1983). 13 Feb. 2007 <http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1983/1/1983_1_50.shtml>.

10 Herbert S. Parmet. "The Kennedy Myth and American Politics." The

History Teacher 24.1 (1990): 31-39.

11 Ibid.

12 Thomas Brown. JFK: History of an Image. Bloomington: Indiana University

Press, 1988.

13 Brown, 35. JFK wanted to prevent a Communist takeover in Vietnam while avoiding

a "large-scale commitment of American troops..." Though he resisted

sending in troops, JFK still drastically increased the number of American "advisors",

the use of U.S. helicopters, and counterinsurgency measures in the fighting.

14 Original source unknown. Cartoon obtained from Baylor University Online

Library, Baylor Collections of Political Materials. See <http://www3.baylor.edu/Library/BCPM/Research/Topics/jfk/pages/jfk1_gif.htm>.

15 John Hellman. The Kennedy Obsession: The American Myth of JFK. New York:

Columbia University Press, 1997.

16 Ibid.

17 Joseph P. Berry. John F. Kennedy and the Media: The First Television President.

Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1987.

18 "Kennedy Prefers 'J.F.K' to 'Jack' for Headlines." New York Times

5 Jan. 1961: 28.

19 Berry, 69. Although Kennedy appeared to get along with the media, he was

constantly at odds with them, mostly due to his efforts to make them "more

objective and accurate." His close watch of the media and requests for

corrections often led to him being accused of news managing.

20 New York Times. The Kennedy Years. New York: Viking Press, 1964. This is

the actual caption for this photograph.

21 Berry, "Kennedy Mesmerizes the Television Audience"; The Great

Debates - Kennedy vs. Nixon, 1960. Ed. Sidney Kraus. Bloomington: Indiana University

Press, 1962.

22 Brown, "Introduction."

23 The Riderless Horse is the single rider less horse with boots reversed in

the stirrups, which follows the caisson carrying the casket in a funeral procession.

In the United States, the Riderless Horse is part of the military honors given

to an Army or Marine Corps officer who was a colonel or above; this includes

the President, by virtue of having been the nation's military commander in

chief and the Secretary of Defense, having overseen the armed forces. Abraham

Lincoln was the first U.S. president to be honored with the Riderless Horse

at his funeral.

24 Hellman, 146.

25 Original source unknown. Cartoon obtained from "Filibuster Cartoons.com." Narrative

with cartoon read: "JFK's death...saw the rise of a lot of people who

tried to profit off the assassination in some way. Writing quick, crappy memoirs

of the president was one surefire money-maker, a practice this particular cartoonist

seems to find offensive." See <http://www.filibustercartoons.com/jfk.htm>.

26 Diana Trilling. "Reflections a Year Later." Redbook November

1964: 71-75.

27 Hellman, 146.

28 Peter A. Jay. "The Myth of Bobby Kennedy, Hero of the Sixties Generation

Still Appeals." Washington Times 18 Jan. 2000: A15.

29 Ronald Steel. In Love With Night: The American Romance with Robert Kennedy.

New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

30 Ibid, 37.

31 Jonathan Yardley. "RFK's Legacy: Liberal Myth." Chicago Sun-Times

16 Jan. 2000: 15.

32 Steel, 18-19.

33 Jules Feiffer. "The Bobby Twins" 29 Jan. 1967. Draw! Political

Cartoons from Left to Right. Ed. Stacey Bredhoff. Wash, D.C.: Nat'l Archives

and Records Administration, 1991.

34 This phrase was often used to describe Robert F. Kennedy. First found source:

Steel, 156.

35 Warren Weaver. "Kennedy: An Apostle of Involvement." New York

Times 7 Jun. 1969: 19.

36 Steel, 167.

37 Robert F. Kennedy. "National Reconciliation." University of

Alabama. Tuscaloosa, 21 Mar. 1968.

38 Robert F. Kennedy. "The Other America." University of Kansas.

Lawrence, 18 Mar. 1968.

39 Evan Thomas. Robert Kennedy: His Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000.

40 Robert F. Kennedy. The Gospel According the RFK: Why it Matters Now. Ed.

Norman McAfee. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2004.

41 Robert F. Kennedy. "Ending the War." Kansas State University.

Manhattan, 18 Mar. 1968.

42 Robert F. Kennedy. "The Art of Peace." Sigma Delta Chi Journalism

Fraternity. Portland, OR, 17 Apr. 1968.

43 Adam Walinsky. "Why We Search for RFK." New York Times 5 Jun.

1988. The author of this article was an assistant to RFK at the Justice Department

and the Senate from 1963-68.

44 Tom Wicker. "A Pall Over Politics: Murder Raises Grave Questions for

Presidency Races Now and in Future." New York Times 6 Jun. 1968: 1.

45 Anthony Lewis. "A Year Without Robert Kennedy." New York Times

4 Jun. 1969: 4.

46 David Levine. Cartoon. New York Review of Books 21 Aug. 1969. Robert Kennedy

is drawn in football uniform, carrying the ball, holding an olive branch (symbol

for peace) in his mouth. The reference to football is prominent throughout

the Kennedy legacy as it was the family sport of choice. This image portrays

Robert charging forward for peace.

47 John F. Harris. "Clinton Calls RFK a Personal Inspiration." Washington

Post 5 Jun. 1998.

48 Donn Esmonde. "RFK Bio Separates Myth from Man." Buffalo News

15 Oct. 2000: H7.

49 Yardley, "RFK's Legacy: Liberal Myth."

50 Don Hesse. Cartoon. El Paso Times 11 Jun. 1968. Drawn five days after his

assassination, the Kennedy brothers are depicted as meeting in heaven, with

Robert lamenting to his older brother that "things haven't changed much..."

51 Gabel, "The Spiritual Truth of 'JFK'."

52 McAfee, The Gospel of RFK: Why It Matters Now.

53 David Levine. Cartoon. New York Review of Books 23 Apr. 1970. JFK depicted

as steady and true on his white stallions.

54 Ibid.