Stitching

a Protest

by

Annette Santomassimo

Social activism

and political protest are unsurprising activities for one such as myself-a

heavily tattooed, radically feminist college student-until, that is, I reveal

the medium of my protest: knitting. The associations we have with traditionally "feminine" fiber arts rarely bring to mind the

words "protest," or "activism;" we generally think of our

grandmothers knitting, quilting and embroidering for their families. Despite

those associations, activism and protest are threads that have been tightly

interwoven through the histories of these three fiber arts at least since the

middle of the nineteenth century. There are so many examples in history where

knitting, quilting and embroidery have been used as mediums for protest and/or

activism that they seem to be uniquely suited for it. This connection could

potentially lend historical significance to these art forms' revitalization

in this first decade of the twenty-first century, particularly as many are

coming to recognize the corporate hegemony, which only encourages consumption.

By making things for ourselves, we are decolonizing our minds; we, like those

who came before us, are creating instead of consuming.

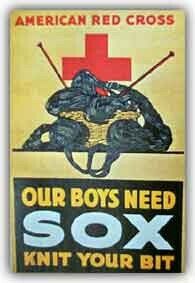

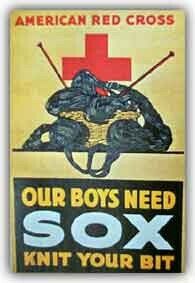

Knit Your Bit

"You ain't sh-- if you don't knit." -Debbie Stoller

World War I Red Cross poster

Possibly the most recognizably social use of knitting in our nation's history

is the wartime knitting phenomenon during WWI and WWII. Upon the United States'

entrance into WWI, the Red Cross distributed over 250,000 knitting pamphlets,

starting a nationwide "knitting marathon" which resulted in the production

of over thirty million garments for soldiers and refugees by the end of the

war.1 The intense patriotism of the times caused wartime knitters to "categorize

nonknitters unpatriotic, and therefore somewhat disreputable."2 Knitting

socks may not seem to be social activism on the surface, but spending nearly

all of one's time engaged in active support of a war effort surely qualifies

as such, especially when it was not strictly necessary. Knitting for the soldiers

became so widespread, the military feared they might gain a reputation for

being unable to meet the soldiers' needs. They emphasized the knitted garments'

status as "luxuries," not necessities. This didn't dampen the knitting

mania, however, as even radical activists were knitting for soldiers. Many

suffragettes packed knitting with their lunches for an afternoon protest on

the White House lawn.3

The knitting effort in WWII was no different, except

that the hand knitted items were perhaps even less necessary with continued

industrialization of the textile industry. Knitting fever returned with the

wartime atmosphere nonetheless; a New York Times article in 1945 stated that

one Mrs. Lilla K. Upton had just finished her 100th war sweater in two years.4

In contrast to this fervent support of WWI and II, wartime knitting in the

twenty-first century has a transformed from support into protest. For example,

Cast Off, a prominent UK knitting group, organized a project to assemble enough

knitted pink squares to fully cloak a WWII tank in protest of the Iraq war.5

Another more local example is a group called Knitting for Dolphins, which is

knitting dolphin sweaters in protest of their potential military use in cold

waters.6

In 2003 Debbie Stoller, editor-in-chief and co-founder of Bust magazine, wrote Stitch

N Bitch: The Knitter's Handbook and gave name to the movement that had

been slowly burgeoning for years. All over North America, Western Europe, and

beyond, knitting groups were forming in coffee shops and cafes. These weren't

your old-fashioned church ladies; these new knitters were hip young moms, globetrotting

executives, artists, college students, and even (gasp!) men. While for some

it was purely for irony's sake, for many at first there seemed almost a "feminist

guilt," to actually enjoy something that feminist writers like Betty Friedan

had labeled as a feminine "duty" which was no longer necessary and

only served as an obstacle for women's true creative expression.7 Stoller,

a prominent feminist, addresses this apparent conflict: "Some 'crafty'

feminists, like myself, are reclaiming what have been called the 'lost domestic

arts,' realizing the importance of giving women's crafts their due." Since

knitting and all the other "lost domestic arts" were traditionally

done by women, they have been relegated to the lower status of "craft" as

opposed to "art." Many contemporary knitters feel they are paying

homage to the under-appreciated women who came before.

Stoller goes on to state another reason for the rise of knitting: "Others

are more interested in freeing themselves from a dependence on what they see

to be an exploitative corporate culture."8 One such group is the Revolutionary

Knitting Circle, a group of guerrilla-style knitters who hold "knit-ins" in

banks, malls and office towers. Their manifesto is a call to action, stating

that

"By returning production of the essentials of life to the community, we

can eradicate the dependence imposed by the elites - giving communities the

freedom to guide their own destinies. We call upon all people who would see

their communities freed from corporate slavery to come forth to share in action

dedicated to removing the production of essential goods from the hands of multi-

national corporations and returning that production to the people."9

This protest rhetoric that they are calling upon is reminiscent of Gandhi's

decolonization tactics when he wove his own clothing from local fibers rather

than buying manufactured goods from the colonizers. Within this framework,

any type of knitting, even that which does not appear to make a statement,

is an act of defiance against the colonization of corporate hegemony.

There are, however, contemporary examples of knitted protest which make their

statement apparent. One type aims to blur the line between "art" and "craft," and

is being offered by knitters who define themselves as fiber artists, rather

than "crafters." A current exhibit at the Museum of Arts and Design

in New York titled "Radical Lace & Subversive Knitting" exemplifies

this sort of protest. The exhibit, which runs from January 25 - June 17, 2007,

features works which transcend the line between art and craft. Some pieces,

like a steel lace wheelbarrow by artist Cal Lane, challenge traditional gender

roles by transforming traditionally masculine objects. Others, like Knit

Lead Teddy Bear, 2006, by Dave Cole (it's exactly what its title states) make use

of unusual materials to challenge the viewer's preconceptions about how knitting

can be used. This exhibit shows clearly just how well suited these mediums,

which are both tactile and highly personal, can be for an artist who wishes

to make a statement.

Patched Together

"May the points of our needles prick the slave owner's conscience."

--Sara Grimke 10

Like knitting, quilting has a long history as a means for women to protest.

The earliest story of quilted protest in the U.S. is of Betsy Ross sewing the

first flag for George Washington-and though contemporary scholarship has shown

the story to be a fabrication, its precedent remains.11 Whether as a statement

of patriotism, radicalism, or anything in between, quilting's association with

women, combined with its heavy use of pictorial symbolism, has made it a staple

in women's protest movements. An early example is the quilting done by slaves

in the South. Denied all other forms of expression, women made use of the "acceptable" activity

of quilting to record their lives. While many quilts made by slaves were designed

by the white mistress and were often made in collaboration with her, there

are numerous examples of quilts designed and executed by slaves. Their uses

of African spiritual symbols and traditional color schemes, such as red and

white, are protests in themselves, while the superior skills of many slave

quilters were a lovely indictment of their supposed "inferiority." Furthermore,

the collaboration on quilts between white women and slaves often served as

a bridge across difference, creating lasting friendships that defied race divisions

and in many cases outlasted slavery.12

Another historically important aspect of quilting as protest is the quilting

bee. For much of our country's history, from the slave cabins of the south

to the country clubs of the northeast, bees were practically the only time

and place where groups of women could talk politics without male influence.

These networks of women were utilized during the suffrage movement as pre-established

channels of organization and communication. The importance of quilting bees

to the suffrage movement is highlighted by the fact that Susan B. Anthony,

the most prominent leader of the suffrage movement, made her first suffrage

speech at a quilting bee.13

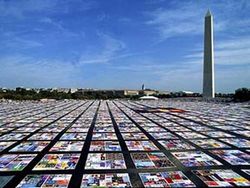

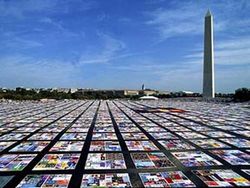

The NAMES Project AIDS Quilt

A more contemporary

example of quilting as protest is the NAMES Project, also known as the "AIDS Quilt." Begun in 1987 as a small-scale memorial

quilt for AIDS victims, the project quickly became a huge phenomenon involving

thousands of quilt panels. The monumental Quilt represents a remembrance of

the victims of AIDS, and also serves as a protest to the silence surrounding

the AIDS epidemic. As one scholar commented, "Panel makers-who include

victims themselves-call for action and challenge social morals through the

Quilt."14

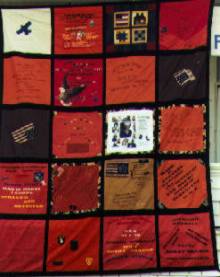

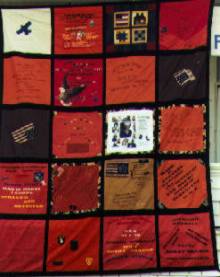

Another contemporary example of protest quilts was shown in a 1992 study where

181 quilters were given a questionnaire about quilts they made during the Gulf

War from 1990-91. Nearly all of the quilters considered the quilts they made

in that period to be "Desert Storm Quilts," even when their appearance

indicates no overt connection. There were a large number of mourning quilts,

easily recognizable anti-war quilts, and even more that were intended as anti-war

even if not recognizable as such. While the author of the study hypothesizes

that quilts made during that war differed from the predominantly patriotic

quilts made during prior wars, she still raises the question, "what would

quilters of previous wars have said about their apparently patriotic quilts,

if they had had the opportunity to reply to a questionnaire or make an artist's

statement?"15 This is a question that could also be asked about knitting,

and about embroidery.

www.gulfwarvets.com

In Stitches

"Has the pen or pencil dipped so deep in the blood of the human

race as the needle?"

--Olive Schreiner 16

Even more than knitting or quilting, embroidery has been historically considered "women's

work" in too many cultures to count. In her groundbreaking work, The Subversive

Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, Rozsika Parker traces the

long history of how "embroidery has been the means of educating women

into the feminine ideal, and of proving that they have attained it, but it

has also provided a weapon of resistance to the constraints of femininity."17

In her final chapter, titled "A Naturally Revolutionary Art?" Parker

explores the idea that because it is so personal, traditionally feminine, and

symbolic in nature, embroidery was a naturally powerful tool of resistance

for women in the twentieth century. While her research focuses mainly on European

and American women, Parker acknowledges that her theories also encompass the

long tradition in places like Soweto and Chile, where embroidery has been a "testament

of survival and resistance in the face of political persecution and racial

oppression."18

www.otherspace.co.uk

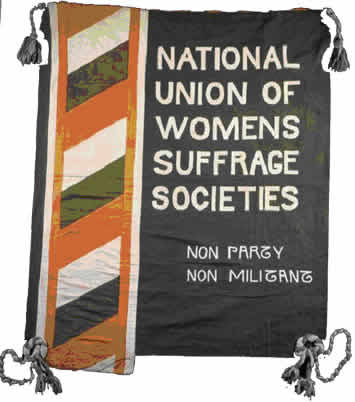

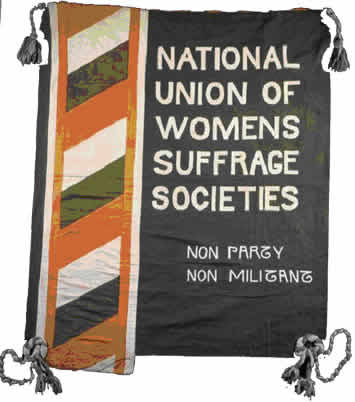

A telling example of embroidered protest in the early part of the century

was present in the banners of the women's suffrage movement. The movement

in the UK had an arts and crafts society called the "Suffrage Atelier," which

was responsible for the creation of their union inspired banners. Their banners,

unlike those of the unions, were hand appliquéd and embroidered with

the intention of evoking femininity as a source of women's strength. Parker

suggests that this use of embroidery was a tactical move, designed to disprove

the propaganda which painted suffragists as masculine creatures.19

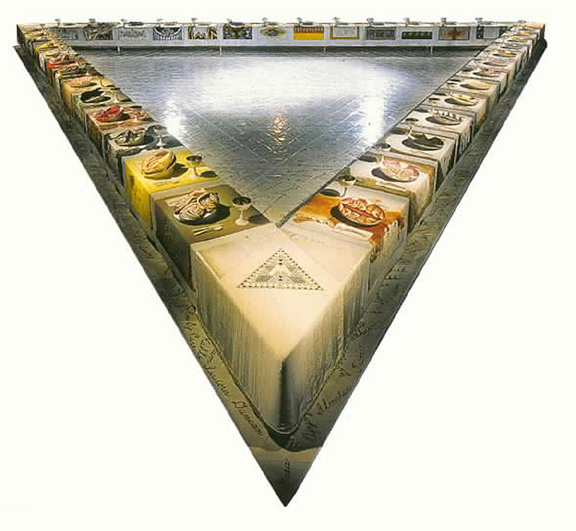

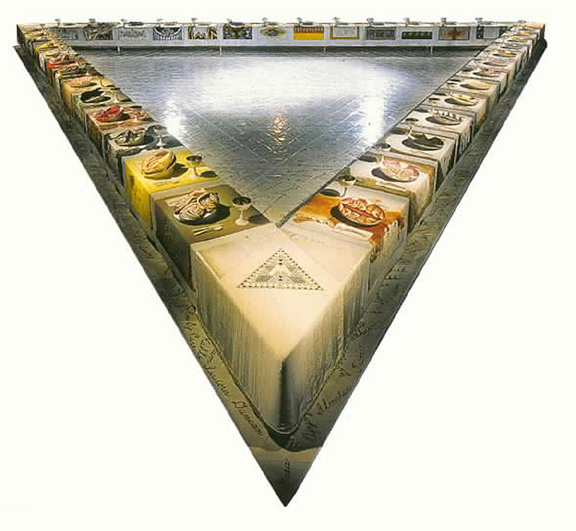

Another, more recent example of tactical embroidery usage is an installation

titled The Dinner Party, originally exhibited in 1979 at the San Francisco

Art Museum. Artist Judy Chicago collaborated with over 400 women and men to

create a large triangular dinner table with 39 place settings, each for a particular

goddess or historically significant woman. Each place setting, designed to

invoke the woman in her historical context, included a hand-made plate, goblet

and cutlery, and a hand-embroidered runner done in the style of each period.

The runners make heavy use of color and symbolism, and the gradually tighter

encroachment upon the plates by embroidery represent increased restrictions

on women's lives over the centuries. The use of needlework for the runners

explores its relationship to those restrictions.20

Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party

And to sew it all together...

"The master's tools can never be used to dismantle the master's

house."

--Audre Lorde

In light of all this protest, it is safe to say that there is a clear connection

between the fiber arts and women's protest. While these mediums were at all

that was available at times to many women for self-expression, often the use

of them is a conscious choice. I am inclined to agree with Rozsika Parker,

who claims that feminists have used embroidery (and knitting, and quilting)

as a means of protest because it shows that the personal is political. Throughout

western history women's personal lives and arts have been dictated and shaped

by the dominant political structure.21 The status of "craft" has

been imposed upon fiber arts because of the racial, gendered and classed context

in which they were made. Pursuing these arts is a challenge to that dominant

structure, along with being a challenge to the canon of what constitutes art

and what constitutes craft. These issues were addressed by the Dada movement

in the early twentieth century, which made use of the applied arts in an attempt

to change of art's place in society. Instead of being owned by the elites,

they tried to "bring art to the masses." These Pre-WWI artists "looked

to peasant art as a means by which indigenous cultural modes could be reinforced

in opposition to the dominant place given to foreign culture."22 I feel

that these sentiments are once again present in our culture where almost everything

is mass-produced. Making objects with our own hands, using the same methods

as our grandmother's grandmother, we are engaging in a decolonization of the

mind. Rather than allowing the imperialism of corporate consumerism to remain

entrenched in our lives, we have the power to make a protest, to revolt. All

we need is a ball of yarn and a couple of sticks.

Works Cited

"A Frostbitten Flipper Defeats the Purpose," The Tacoma News Tribune

2 Mar 2007: B1.

Armstrong, Nancy C. Quilts of the Gulf War, Desert Storm-Participation or Protest?" Uncoverings

Vol 13 1992: 9-44.

Atkins, Jacqueline M. Shared Threads: Quilting Together-Past and Present. New

York: Viking Studio Books, 1994.

Chicago, Judy. Embroidering Our Heritage: the Dinner Party Needlework. Garden

City, NY: Anchor Books, 1980.

Edelson, Carol. "Quilting: a History," Off Our Backs. Washington:

31 May 1973. Vol. 3, Iss. 8: 13.

Finley, Ruth. Old Patchwork Quilts and the Women Who Made Them. Newton Centre,

Mass: C.T. Branford Co, 1970, c1929.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1963.

Fry, Gladys-Marie. Stitched From the Soul: Slave Quilts from the Ante-bellum

South. New York: Dutton Studio Books, 1990.

Gunn, Virginia. "From Myth to Maturity: the Evolution of Quilt Scholarship." Uncoverings

Vol 13 1992: 192-205.

Lewis, Barbara. "UK: Knit and Make a Statement," Women's Feature

Service. New Delhi: 31 Oct, 2006.

Macdonald, Anne. No Idle Hands: The Social History of American Knitting. New

York: Ballantine Books, 1988.

Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine.

London: Women's Press, 1984.

Revolutionary Knitting Circle. 20 Feb 2007 <http://knitting.activist.ca/manifesto.html>.

Ruskin, Cindy. The Quilt: Stories from the NAMES Project. New York: Pocket

Books, 1998.

Stoller, Debbie. Stitch N Bitch: The Knitter's Handbook. New York: Workman

Publishing Co., 2003.

"War Sweater Maker Knits 100th," The New York Times 18 Dec 1945:

24:1.

Williams, Mary Rose. A Re-conceptualization of Protest Rhetoric: Characteristics

of Quilts as Protest. Dissertation, University of Oregon, 1990.

1 Anne Macdonald. No Idle Hands: The Social History of American Knitting.

New York: Ballantine Books, 1988.

2 MacDonald, 224.

3 MacDonald, 229.

4 "War Sweater Maker Knits 100th." The New York Times 18 Dec 1945:

24:1.

5 Barbara Lewis. "UK: Knit and Make a Statement," Women's Feature

Service. New Delhi: Oct 31, 2006.

6 "A frostbitten Flipper defeats the purpose," The Tacoma News Tribune

2 Mar 2007: B1.

7 See Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique.

8 Debbie Stoller. Stitch N Bitch: The Knitter's Handbook. New York: Workman

Publishing Co., 2003, 10.

9 Revolutionary Knitting Circle. Feb 20, 2007 <http://knitting.activist.ca/manifesto.html>.

10 As quoted in Atkins, Jacqueline M. Shared Threads: Quilting Together-Past

and Present. New York: Viking Studio Books, 1994.

11 Gunn, Virginia. "From Myth to Maturity: The Evolution of Quilt Scholarship." Uncoverings

Vol 13 1992: 192-205.

12 For a detailed discussion, see Gladys-Marie Fry. Stitched From the Soul:

Slave Quilts From the Ante-bellum South. New York: Dutton Studio Books, 1990.

13 Carol Edelson. "Quilting: a history," Off Our Backs. Washington:

May 31, 1973. Vol. 3, Iss. 8; 13. Also mentioned in Ruth Finley. Old Patchwork

Quilts and the Women Who Made Them. Newton Centre, Mass: C.T. Branford Co,

1970, c1929.

14 Mary Rose Williams. A Re-conceptualization of Protest Rhetoric: Characteristics

of Quilts as Protest. Dissertation, University of Oregon, 1990. See also Cindy

Ruskin. The Quilt: Stories from the NAMES Project. New York: Pocket Books,

1988. And Atkins, Shared Threads, 1994.

15 Nancy C. Armstrong. "Quilts of the Gulf War, Desert Storm-Participation

or Protest?" Uncoverings Vol 13 1992: 9-44.

16 As quoted in Rozsika Parker. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making

of the Feminine. London: Women's Press, 1984.

17 Parker, The Subversive Stitch, 1.

18 Parker, 192.

19 Parker, 197-8.

20 Parker, 209-10. See also Judy Chicago. Embroidering Our Heritage: the Dinner

Party Needlework. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1980.

21 Parker, 205, 209.

22 Parker, 191-3.