Bryan

Cross

What’s Going On:

A Social Commentary by Marvin Gaye

|

Bryan

Cross |

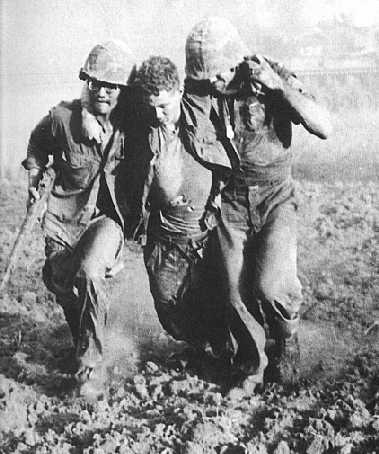

In

1971 America was still involved in a war ‘defending’ democracy in

Vietnam. The Pentagon Papers, which were secret government documents pertaining

to American involvement in Vietnam, were leaked through The New York Times.

Continuing the exploration of the moon, Apollo 15 produced more lunar information

than all other space missions combined and President Nixon became the first

President to visit Communist China. It was a year scarred by social, political,

international and economical turmoil. Musically, one of the brightest moments

during that time of uncertainty came on May 21st when Motown Records, located

in Detroit, released the Marvin Gaye masterpiece What’s Going On. The

reason that What’s Going On stands out as a masterpiece is because it

went beyond the music conceptually, and became a ‘concept’ in its

approach as a social commentary.

Marvin

was Motown’s leading soul singer and until What’s Going On was made,

he and others were never given the freedom to write or sing their own music.

In the biography, Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye, David Ritz quotes Marvin

when referring to the artistic confines of Motown, “The notion of singing

three-minute songs about the moon and June didn’t interest me.”(140)

Marvin sang, composed and produced What’s Going On, with the help of other

musicians and writers, making the album pioneering both musically and thematically.

The

album What’s Going On can be viewed as forms of music, poetry, or art.

It can also be looked at as a protest, a statement or narrative. The album used

all these different perspectives and combined them, creating a mosaic made of

themes that questioned the social, political and economical condition of America.

As a result, the listener is given a frame of reference in which to question

his or her own living history.

Referring

to the social and global condition of the 1960s that spawned many civil and

artistic protests, Edmonds, in “I Can See Clearly Now,” writes that

when What’s Going On was recorded and released, “…[it] was

a little late [for Marvin] to hop on the bandwagon.”(79) He goes on to

mention that the album was “…told from the point of view of a returning

vet, a disconnected vet, a drug addict, ecological disaster and economical desperation.”(78)

In these terms it becomes easy to see that the content of the album resides

more in the confines of a social commentary yet remains a lyrical, musical and

artistic protest to the events that took place at the time of the album’s

release.

The

question mark is absent from What’s Going On because it is meant to be

statement and an opening for dialogue. It is also a phrase that encapsulates

the times and frame of reference that Marvin is preparing to establish. In that

way, the phrase takes on a significantly different meaning i.e. this is going

on as opposed to the implied question: what is going on?

When

What’s Going On starts to fill the ears of the listener, one becomes enthralled

within the swirling symphonic echoes set against a juxtaposition of conga drums

and an orchestra. The content of the album by and large is set up in the same

dichotomous way as the music itself. Within the songs of reflection and despair,

Marvin offers hope through salvation and both messages become interwoven by

the bleeding of one song’s ending merging with that of the next song’s

beginning. The continual sense of different themes coinciding through the music

sets the album apart from being just ‘songs of protest’ to an album

that looks at a greater, larger scale when concerning humanity.

The

opening track, “What’s Going On,” represents a statement that

sets the stage for the rest of the album. There is a conversation already taking

place, opening a proverbial ‘door’ to the listener, as if to invite

them to ‘sit-in’ and take part. The sounds of people chatting, throwing

out catch phrases that were hip to the 1960’s in particular, ‘What’s

happening?’ ‘Can you dig it?’ ‘Everything is everything.’

‘Solid!’ act as reflections to a recent past since these terms were

out dated by the time they were used and function to establish the time frame

of the commentary. Marvin starts by referring to the conflict in Vietnam, “…You

see, war is not the answer/For only love can conquer hate…” Then

he shifts the listeners perspective to focus on the conditions at home,”

everybody thinks we’re wrong/Oh, but who are they to judge us/Simply because

our hair is long…Picket lines and picket signs/Don’t punish me with

brutality…” This refers to the Civil Rights movement that happened

from 1954-1965. It could also refer to the white students gunned down at Kent

State and the lesser-known black students, also gunned down, in their dormitory

at Jackson State College. He goes on with, “What’s going on/ Yeah,

what’s going on/Tell me, what’s going on/I’ll tell you what’s

going on.” He starts to interpret the events in forms of questions that

act to foreshadow the thematic nature of the album.

If the song ‘What’s Going On’ refers to the struggles in Vietnam, then Marvin brings the struggle home in the second song, “What’s Happening Brother.” Marvin uses the dialogue of the returning veteran to ask the question: what’s going on? “War is hell, when will it end, /When will people start gettin’ together again.” And he continues with “Are thing really gettin’ better like the newspaper said/What else is new my friend, besides what I read/Can’t find no work, can’t find no job my friend/Money is tighter than it’s ever been/Say man, I just don’t understand/What’s going on across this land…” This song and “What’s Going On” foreshadow the disparity that starts to take place in the up coming themes.

On the third track, “Flyin’ High (In The Friendly Sky), the album

lulls musically and creates a ‘drug-induced’ like state. According

to the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs, between the years of 1960-1970,

Detroit saw the active drug addict population increased by 89%. (649) That stunning

change had to have some influence for Marvin to addresses the topic of drug

addiction.

The song’s implication is clear from the beginning, “Flyin’

high in the friendly sky/Flying high without ever leavin’ the ground…”

Marvin sings a duet with himself, one voice as a ‘hooked’ addict,

and the other as the soul of the addict struggling with that addiction. The

addict sings “So stupid minded, /I can’t help it…I go to the

place where good feelin’ awaits me and it’s bound to forsake me...”

while in the background the ‘soul’ can be heard echoing “Can’t

help it”, “Gotta have it” and “Self-destruction in my

hand.” The addict ‘wins out’ over the soul in the end and

faces his reality, “Well I know I’m hooked my friend/To the boys

who make slaves out of men.”

Without missing a beat “Save the Children” continues the intentional

slow down of the tempo, which serves as the conscience of the album. Once again

Marvin uses two different vocal styles, the spoken word and the singing voice,

one talking and the other singing as if to symbolize oneness in duality. This

is the first song to essentially pose a blatant question. Marvin in a low tone

and sleepy style starts the song with, “I just want to ask a question/Who

really cares? /To save a world in despair/Who really cares?” And then

begins to answer himself by singing, “When I look at the world it fills

me with sorrow/Little children today are really gonna suffer tomorrow…You

see, let’s save the children/Let’s save all the children/Save the

babies, save the babies…” The duality of images are apparent and

similar to “Flyin’ High (In The Friendly Sky).

The social commentary of “Save the Children” directly reflects the

events that happened in Birmingham years earlier as described by Juan Williams

in Eyes on the Prize. Children were marching and protesting when Police Chief

Bull Connor ordered police dogs to attack and firemen to use hoses that sprayed

“100 pounds of pressure per square inch”(190) into the demonstration.

In an abstract reflection concerning children, the song also refers to the tens

of thousands of young men fighting and dying in Vietnam at the time.

Marvin, as a child, spent time in the church where his father preached. The

churches impact and influence on Marvin allowed him to explore salvation, through

a redemptive belief in God, and is paid special attention to in the songs “God

Is Love”, “Right On” and “Wholy Holy.” In these

songs Marvin reflects the non-violence preached by Martin Luther King Jr. in

a way that looks at love as an answer to the times of despair. In “God

Is Love” Marvin, stressing the emphasis on family, sings “Love your

mother, she bore you/love your father he works for you/Love your sister she

good to you /Love your brother, your brother.” Marvin implies that salvation

can only take place by spreading love from family to community and a belief

in a higher power, “God is my friend/Jesus is my friend/For when we call

on him for mercy Father/He’ll be merciful my friend/Oh, yes he will/All

He asks of us, I know, is we give each other love.” In the song “Right

On”, he merges the despair with the promise of salvation through God and

love, “…Some of us are aware/That it’s good for us to care/Some

of us feel the icy wind of poverty blowing in the air…Love can conquer

hate every time/Give out some love and you will find peace sublime…”

In the article “Trouble Man: The Art and Politics of Marvin Gaye,”

Mark Anthony states that “Gaye’s solution to the deterioration of

America’s social fabric, a solution indicative of King’s influence

on Gaye’s work, was to reevaluate the role of human respect…”(254)

While the tempo of the music has slowly increased by this point in the album,

“Wholy Holy” brings it back to a slower, somber pace that serves

as the conscience similar to the earlier songs “Flyin’ High (In

The Friendly Sky)” and “Save The Children.” Love, as a movement,

resembles the non-violent activities of the Civil Rights movement and a hope

can be seen in the lyrical content of the song. For example, “We can conquer

hate forever, yes we can/Ah, wholy holy/Oh, Lord/We can rock the world’s

foundation/Yes we can…Holler love across the nation.” In that regard,

the Civil Rights movement could be an example to the world as a whole; instead

of the segregated Southern states themselves.

In his book, Trouble Man: The Life and Death of Marvin Gaye, Steve Turner subtly

uses Marvin’s life to suggest a possible reason for composing What’s

Going On. “…[Marvin] became conscious of his own ‘black identity’.

Reading Malcolm X and Dick Gregory, with whose outrage he identified…”(107)

The anger, or outrage, that is represented in Marvin’s music is dealt

with in the form of questions, in reflections and as interpretations of the

world in which he lived and the generation that he was summarizing.

Mary Ellison in the preface of her book Lyrical Protest: A Black Music’s

Struggle Against Discrimination writes about the expression of that anger. “[The]

roots of African music joined with an African -American music reveals emotions

and responses to slavery, blues, [oppression]…” Furthermore, she

states that “…the most fascinating aspect of [this music] and those

that they spawned is that the anger they express is not contained by the music

but flows out into the attitudes and actions that seek to fight discrimination

and unjustified aggression.”(Preface) It is in this context that Marvin

explained why he was inspired to write about the conditions and events he had

witnessed.

“Something happened with me during that period. I felt the strong urge to write and to write lyrics that would touch the souls of men. And in that way I thought I could help.”(Liner notes)

The example set by Marvin’s music and the way it came about deserve a

closer examination when considering its impact and influence on other artists.

Ben Edmonds, in his essay “A Revolution in Sound & Spirit: The Making

of What’s Going On,” writes that the album “…liberated

the Motown assembly line and set new benchmarks for artistic expression…”(5)

It was the first time Motown had printed the lyrics and gave credit to the writers

and musicians on an album. Edmonds continues with, “At long last the Funk

Brothers and all the other musicians were given names and public acknowledgment.”(9)

Ellison argues that, What’s Going On, created an environment for other

artists such as Curtis Mayfield and Stevie Wonder to “…question

every political assumption thrown at them.”(67)

Dave Marsh, editor of The New Rolling Stone Record Guide, also attests that

What’s Going On “…open[ed] the door in terms of lyrics and

music.”(193) He goes on to mention that “…’Mercy, Mercy,

Me’ and ‘Inner City Blues [are] hopeful songs about black urban

life that disregarded the romanticism of Gaye’s (and Motown’s) past.

(194) Like Ellison, Marsh argues that What’s Going On directly influenced

the ‘concept’ albums, Innervisions by Stevie Wonder and Superfly

by Curtis Mayfield.

Marvin’s music had influenced other artists, and he had been influenced

by his immediate surroundings and national events. The Food and Drug administration,

in 1971, advised “… [The] American public to stop eating swordfish

because more than 90 percent of samples tested contained excessive amounts of

mercury.”(54) The day that What’s Going On was released The New

York Times released a new analysis by Boyce Rensberger that read “Mercury

and Man: A Puzzle for Ecologists.” “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)”

combines the environmental issues of the times while offering a gloomy outlook

of a possible future. He sings, “oil wasted on the ocean and upon our

seas, fish full of mercury/Ah oh, mercy, mercy me…” He then refers

to the ‘Mother Earth’ and asks “What about this overcrowded

land/How much more abuse from man can she stand?”

In

addressing both social and global issues, the song acts as a reminder of the

thematic nature intended in Marvin’s artistry.

It’s fitting that the last song on the album is “Inner City Blues

(Make Me Wanna Holler).” It forms a mosaic from the themes in which Marvin

summarizes throughout the album. It becomes a reflection of a reflection, a

body of work that not only encapsulates the album as a whole, but also the time

period. If the images he has created have yet to fulfill or enlighten the listener

up to this point, then this last track becomes his ‘swan song.’

The lyrics to “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)” almost read like a daily newspaper or eleven o’clock news broadcast from 1971. The New York Times issue that published the article about mercury was also filled with headlines and stories that mirrored the contemporary events against those events that Marvin was singing about. They read: Allied and Enemy War Deaths Decline, Census Finds Inflation Erased Gain in Family Income in 1970, Nixon’s Racial Stance and Experts See Soviet and U.S. Nuclear Arsenals in Rough Balance. He refers to Government spending and taxes, “Rockets, moon shots/Spend it on the have nots/Money, we make it/’Fore we see it, you take it…” Inspired again by social events, Marvin explains the condition of urban developments, “…Inflation, no chance/To increase finance/Bills pile up sky high/Send that boy off to die/Make me wanna holler/The way they do my life…”

In the 1960s, the gloomy economical condition in Urban-America led to major

insurgencies in the cities of Watts, Newark, and Detroit. The riots of Detroit

lasted nine tumultuous days that saw police and National Guardsmen defending

the city from rioters and looters. In the preface to his book, The Detroit Riots

of 1967, Hubert Locke mentions that the riot was a “…costly battle:

43 dead, over 700 known injured, some $50 million [in] property damage…Detroit

had just been through the worst experience of urban violence in the nation’s

history.”(51)

Whether from the point of view of ‘how’, or the more difficult,

‘why’, much has been written about the events that led up to, caused,

and happened concerning the riots. The editor of Afro-American History: Primary

Sources, Thomas R. Frazier writes, that “Most of the disturbances were

triggered by incidents involving the visible symbol of white oppression, the

policeman.” and were “Built on the frustrations of the black ghetto

dweller and the student activists…”(435) Still living in Detroit,

Marvin’s point of view was personified and he didn’t sing out against

the riots but rather because of them, “Crime is increasing/Trigger happy

policing/Panic is spreading/God knows where we’re heading/Oh, make me

wanna holler/They don’t understand/Make me wanna holler…”

It’s easy to see how the inspiration and influence for Marvin’s

lyrics came directly from his immediate surroundings.

The last lines that the listener hears on the record are, “…Everybody

thinks we’re wrong/Who are they to judge us/Simply cause we wear our hair

long,” and refers back to the first song “What’s Going On.”

The echoes of friends talking in a party-like atmosphere resurfaces only to

fade away again, essentially returning the listener to the proverbial ‘door’

and the dialogue that originally took place reminding the listener to think

about what they have just heard.

Listened to in its entirety, What’s Going On tells a story of hope, despair and frustration. Marvin’s commentary was a summary and compilation of the events that surrounded him. Inspired by the turmoil, conflicts and desperation of the times, its easy to see why Edmonds refers to the album as being “…captured, not recorded.”(9)

A sense of timelessness is established from the beginnings of “What’s

Going On” to the end of “Inner City Blues (Make me Wanna Holler)”

and the album’s timelessness makes the themes that Marvin addressed as

relevant today as they were thirty years ago.

The song “What’s Going On” as a narrative portrayed the turmoil

and urban condition as events. What’s Going On as an album questioned

the events and remained a work of art that engaged the listener. The music made

the listener think and question their surroundings and living conditions. More

importantly, What’s Going On, depicted a history that cannot be erased,

changed or modified.

Regardless of the ways that the album can be defined, viewed, interpreted or

heard, it exists in the form of music, poetry and art. It is a protest, a statement

and narrative. The musical way that the album summarizes the generation that

preceded its release, while simultaneously protesting the issues of current

every day struggles, makes What’s Going On one of the greatest artistic

statements of the 20th Century.

Annotated Bibliography

The sources contained in this bibliography were used for a study on the social

commentary of Marvin Gaye’s album What’s Going On. Primary, secondary

and historical sources were explored in hopes of giving a well-rounded approach

to the main topic.

Anthony, Mark. “Trouble Man: The Art and Politics of Marvin Gaye.”

The Western Journal of Black Studies. Vol. 22, No. 4, 1998. Ebsco, online.

Anthony looks at the trilogy of Marvin’s albums What’s Going On,

Trouble Man and Let’s Get It On giving special attention to Marvin’s

life and influence on others from the time that What’s Going On was released

until his death.

Edmonds, Ben. “I can See Clearly Now.” 1 Mojo Mar. 1999 issue 64

p62-80.

Edmonds’ focus is the making of the album instead of the messages contained

in it. The overall impression that Edmonds gives is that the record was barely

made, and “…made under the influence of drugs.”(76) The article

also gives a behind the scene account to the making of the music.

Ellison, Mary. Lyrical Protest: A Black Music’s Struggle Against Discrimination.

New York: Praeger, 1989.

As the title suggests, the book as a whole looks at the discrimination towards

African-Americans throughout history and the protest of black music against

discrimination.

Frazier, Thomas R., [et al]. Afro-American History: Primary Sources. New York,

Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. 1970.

A chronological look at African-American history through primary documents that

starts by covering the journals of slaves and concludes with defining black

power. The book covers the topics of segregation, militancy, and non-violence

and all are told from the African-American perspective.

Gaye, Marvin. What’s Going On: 30-Year Anniversary Edition. Motown Recording

Company, 2001.

Originally released in 1971 this special edition CD contained liner notes that

included an essay by Ben Edmonds entitled “A Revolution In Sound and Spirit:

The Making of What’s Going On.” The article and liner notes were

used as references pertaining to Marvin and the album in particular.

Golenpaul, John, editor, [et al]. Information Please Almanac. Doubleday &

Co., Inc.; New Jersey, 1947-present.

The almanac has a multitude of statistics and was used for the year 1971. The

statistics stated in the opening paragraph of the research paper, along with

the The Food and Drug Administration and Bureau of Narcotics And Dangerous Drugs

were from this source.

Locke, Hubert G. The Detroit riot of 1967. Wayne State University Press, 1969.

Locke examines the riot itself, Detroit from 1943 to 1967, and addresses the

aftermath of the violence. The book contains maps and pictures helping the reader

get an idea of the place and time of the event.

Marsh, Dave, and John Swenson. The New Rolling Stone Record Guide. New York:

Random House, 1983.

This collection of music album reviews is a comprehensive guide pertaining to

musicians and their albums as of 1983. A detailed review was given of What’s

Going On and it was used to show relation between his work and others.

Ritz, David. Divided Soul: The Life and Death of Marvin Gaye. New York: DaCapo

Press, 1985.

The biography that Ritz writes compiles many personal interviews with Marvin

and tells the story of Marvin from his childhood up until his death. The book

paints a sad picture of the life of Marvin and that makes his music stand out

more as artistry as opposed to just music.

The New York Times. New York: Friday, May 21, 1971.

The paper was used to show what was happening when the album was released and

to show examples of headlines that mirrored the thematic nature of What’s

Going On.

Williams, Juan. Eyes on the Prize. New York: Penguin Books, 1987.

This book is a comprehensive guide to the Civil Rights movement from the years

1954-1965. Useful source directly pertaining to the movement and its effects.