1

1American Pilgrimages, American Shrines, American Transformations

by John Keeffe

1

1

As I prepare for my personal pilgrimage this year on the Camino de Santiago de Compostelo, I am drawn to view Twentieth Century America in the same light. What are our holy shrines? What is it that matters about these destinations? And what are the forces that draw, or drew, us to them? There is power in the shrines we build, but the real power is in what the pilgrims bring to them. "I am convinced that pilgrimage is still a bonafide spirit renewing ritual. But I also believe in pilgrimage as a powerful metaphor for any journey with the purpose of finding something that matters deeply to the traveler."2

A pilgrimage is the journey that the pilgrim undertakes. Pilgrimage has roots

in most religions and societies. Some pilgrimages are required, such as the

hajj to Mecca, which is a journey all Muslims are supposed to undertake during

their lifetimes. Others come out of powerful personal desires. Hindus go to

the Ganges River to bathe and be spiritually cleansed. Christians travel to

the Holy Land to be near the places of Jesus.

There is more to the act of leaving home and going on pilgrimage. It is not

only about being compelled to go. Pilgrims journey for many reasons. "The

pilgrim's motives have always been manifold: to pay homage, to fulfill a vow

or obligation, to do penance, to be rejuvenated spiritually, or to feel the

release of catharsis."3 While the reasons are many and personal, the concepts

are similar.

The pilgrimage I am personally about to undertake is called the Camino de Santiago

de Compostelo. It is a path that has been walked for over a thousand years.

4

4

As I contemplate the 500 mile journey in front of me, I think about all the

pilgrims, all over the world, and their reasons and feelings about their pilgrimages.

What is it that compels us to leave home? What is it we seek? In America our

shrines are more secular than religious, yet these sites are still imbued with

emotion, spirituality and meaning. We are not an old country and our shrines,

therefore, are new. But the power for the wayfarers who travel to them is the

same as all the worlds' older sites. I have talked of the motives of pilgrims,

but it is often deeper than that. The pilgrim who starts out is not the pilgrim

who returns. The act of walking, or traveling by whatever means, to a shrine

has power in and of itself. "Pilgrimage is about opening ourselves to

change and growth, and inviting new experiences to alter our perspective."5

The pilgrim on the Camino to Santiago or the road to Graceland is seeking a

transformational experience. It is often not in the shrine we visit, but in

the journey to get there. "If the tourist is a consumer, venturing forth

to acquire something tangible to prove she has been there, then the pilgrim

is more like a participant observer, pausing on the path to take stock of where

she has been and where she is going." 6

In the study of twentieth century American history, I have found that we have

shrines here and pilgrims who travel to them. They go in search of something

of importance to them. The ones I chose to explore are not religious sites.

They do, however, connect the traveler at a spiritual level to the meaning

of the shrine. Some pilgrims like those who came to America through Ellis Island,

were seeking a better life in a physical as well as spiritual sense. They came

out of poverty and persecution in hopes of more. Ellis Island was the gateway

for millions to the promised land of America. It was the end of a long, sometimes

perilous trek and at the same time the beginning of a new, hopefully better

life. Graceland is the holy land for Elvis Presley fans. It is where he lived,

died and where he is buried. Those who go to Graceland connect with who Elvis

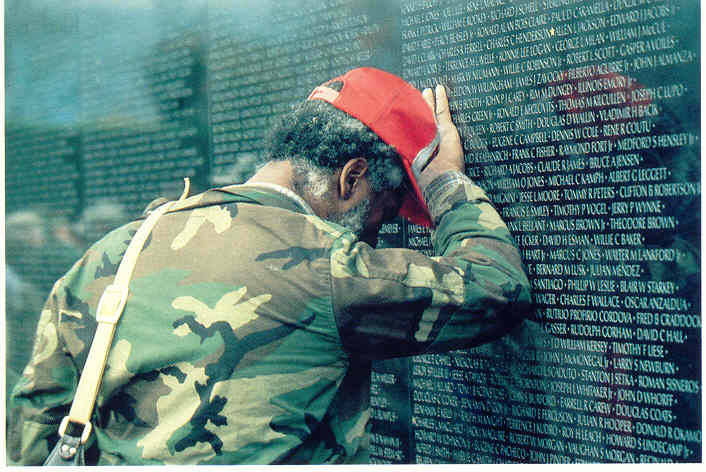

was and what he, and his music, meant to them. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial

(the Wall) is a touchstone for all the anguish that was experienced during

that turbulent period. It is a place of prayer, closure, pain and remembrance.

It is a shrine where people go to try and find meaning. "We go to these

places to remember specific events, and fuse the past and present together

in an unbroken chain of meaning."7

8

8

Ellis Island was opened in 1892 as the main port of entry into the United States for new immigrants. Four out of ten American today had ancestors who came through Ellis Island. From 1892 through 1924 over 14 million immigrants, over 70% of the total immigration during that period, came through its doors. Prior to this time, the screening of immigrants was left up to the states. Castle Gardens in New York City was so notorious that the Federal Government stepped in and created the portal at Ellis Island as a substitute. I consider it a pilgrimage shrine and the immigrants as pilgrims, because of the journey undertaken to get there. Some of the immigrants came to escape religious persecution. Others came because of the economic promise of America. Most of them had no idea what to expect other than it couldn't be any worse than where they were. "Golda Meir later recalled: 'going to America then was almost like going to the moon...We were all bound for places about which we knew nothing at all and for a country that was totally strange to us'."9

If a pilgrimage is a journey of transformation, the Ellis Island was the gateway

for undergoing that transformation. It was not a glorious shrine for the people

going through it. It was also called the Island of Tears.

"They had come from many different countries. Each had his or her own

reasons for coming. But they shared many things as well: the difficult ocean

voyage, the fear of the unknown, and, most of all, the dream of freedom in

America. Now they were about to share another experience they would never forget

-Ellis Island and the ordeal that would decide whether or not their dream would

become a reality."10

11

One of the first lessons upon arriving was that America was not as classless

as the immigrants thought. First and second-class passengers were let off the

ship in New York City. The people in steerage were the ones who were sent to

Ellis Island. Once on the island they were separated by sexes, herded into

the main hall and required to undergo examinations by doctors, looking for

contagious diseases or physical defects; and by a legal inspector. There were

many rules and they didn't all make sense to the immigrants. Women wouldn't

be let in without being claimed by a man, their husband or a male relative.

You had to be able to read, have money, twenty or twenty-five dollars, and

have no prearranged job waiting for you. At the end of the Hall of Registry

there was a stairwell called the Stair of Separation. There were three dividers

on the stairs. One aisle went to the waiting ferries of trains that would take

you to America. Another aisle went to the hospital for those who were sick

but curable and would be allowed in as soon as they were well. The third was

for those souls who were being deported back to their home countries. "When

we got to Ellis Island, I went one way and my family went another. I don't

know what happened to them. They brought me to the hospital. I was there for

23 days."12

Added to the uncertainty and fear the immigrants/pilgrims were undergoing,

there was also a lot of confusion. There were thousands of people going

through the processing center every day. Often people had to wait on the

ships that brought them for days until they could get to the island. "But

then we docked in the harbor. Ellis Island was too crowded. There was quite

a few boats from other ports. Each boat had to wait their turn. I don't

remember how many days we anchored, but it was quite a few days."13

Once on the island the confusion intensified. Families landing were yelled

at to drop their luggage; men were told to go one way and women and children

another and you prayed you would meet up at the other end. It was a traumatic

event.

14

14

"We had left home behind; we were not approaching a new home, only an

indefinite spot in an unknown vacuum...and even if our early hopes had lasted

for a few hours, the miseries of Ellis Island would have wiped them out

efficiently...We were shunted here and there, handled and mishandled, kicked

about and torn apart in a way no farmer would allow his cattle to be treated."15

Ellis Island was a shrine of pilgrimage because it was a gateway. It was the

entrance to America; the end of one journey and the beginning of a new one.

No matter how hard it was on Ellis Island, after you got through, you were

free. For a Jewish immigrant fleeing from persecution it was being able to

say: "'You're in America now. You have nothing to be afraid of. Nothing

at all.' He explained to her (wife) that you could go out in the street and

you could mingle with people."16 As bad as it was on Ellis Island it was

still was a powerful first memory of America. As Bob Hope, who went through

Ellis Island in 1908, said:

"Years later... I was doing some sort of publicity thing down near the

harbor. I just remember staring out over the water to Ellis Island and the

statue, and remember feeling grateful, very lucky, and saying to myself 'thank

you.' Thanks for the memory. That was the first song I sang in the movies with

Shirley Ross and it was such a hit, I just kept on doing it. But emotionally,

when I hear it, I think of that day we arrived at Ellis Island. I don't think,

in all my years, I ever told anyone that."17

Ellis Island was officially closed in 1954. There were calls for the sale of the island, but in 1963 President Lyndon Johnson designated Ellis Island a part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument. In 1990 the main building was reopened after extensive remodeling. Since the remodel was completed millions of visitors have visited Ellis Island. It no longer has the same fear and angst as it did for the immigrants. But the new pilgrims can still feel the power in the great hall. It is a quiet place now and doesn't have all the railings and fences that funneled the hopeful masses through their ordeal. There is a computerized library there now that has all the old lists of the immigrants who came through here, the ships they sailed on and the ports they left from. Many of the new pilgrims who come here to see where their ancestors began their American journey also come to find the record of their arrival here. It is a very emotional experience to realize that you stand in the actual place that your grandfather or grandmother once stood. It is a shrine for those who entered through it, and those who go now to honor their sacrifices. "

19

19

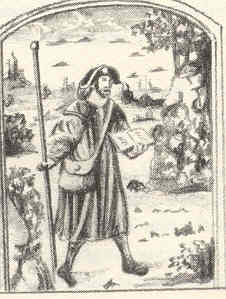

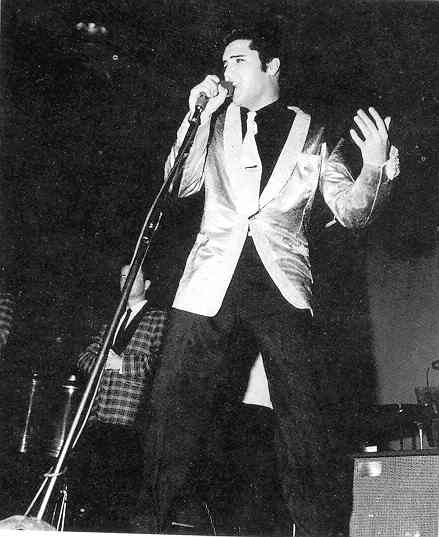

The opportunity to visit Graceland can transform even casual fans into spiritual pilgrims who seek what all pilgrims have desired since time immemorial: a sense of connection, a moment of transformation, and guidance on intensely personal matters."18 Graceland was the house Elvis bought in 1957 for $100,000. Graceland was originally the name of the five hundred acre cattle ranch established in 1861 by S. E. Toof. He named it after his daughter, Grace. The house called Graceland was built in 1939 by Grace Toof's niece, Ruth Moore. Elvis was living in a bungalow style house with his parents and fans would just wander up and hang out in the carport. It was fine for a while but became increasingly out of control so his parents went looking for a new home. Graceland was perfect. Yet even at Graceland, if Elvis wasn't at home, his father would let fans into the house. It seems remarkably relaxed considering how protective stars are today.

21

21

The fact that Elvis was a megastar is not in question. He sold more records than anyone else. He was idolized by all kinds of people, especially females. As big as he was/is, what was it about Elvis that has created the desire for so many people to travel to Memphis and visit Graceland? "Elvis was not a phenomenon. He was not a craze. He was not even, or at least not only, a singer, or an artist. He was that perfect American symbol, fundamentally a mystery, and the idea was that he would outlive us all-or live for as long as it took both him and his audience to reach the limits of what the symbol had to say."20 As a singer and performer he changed music. His style changed rock and roll and his stage presence added a sexual quality to his sound. He was a new vision, and America didn't know how to deal with it. Screaming fans weren't the only ones impressed. Musicians were also changed by him. Bruce Springsteen said about the music of Elvis: "It was like he came along and whispered a dream in everybody's ear and then we dreamed it."22 Over 600,000 people visit Graceland every year. Not all are pilgrims. Some are just fans and some go for the gaudiness of the place. Over half of the visitors are under the age of 35 and so they have no personal memory of Elvis. Many are pilgrims and, of those, there are some who move to Memphis so they can be close to him. "We came here, got in with the Elvis thing, made good friends, bought a house and here we are...We go once a week to Graceland. He was so dear to us and a landmark in so many people's lives. A lot of love and friendships are made through Elvis."23

24

24

We live in a celebrity-obsessed culture and Elvis was called the King for good reason. But while the culture moves on from other celebrities, Elvis' stature grows. His music continues to grow. Graceland gets almost as many visitors per year as the White House. For many, Elvis' songs are what got them through tough spots in their lives. Some of our strongest memories are those that are wrapped in emotions. The songs and circumstances are tied together as one. "Fans feel that Elvis was there with them through thick and thin, in all kinds of circumstances-the joy of first love, the senseless devastation of the Vietnam War-because they never stopped listening to his music during those times, and will always associate certain songs with those intensely personal moments."25 It is this intense emotional attachment that gives Elvis and Graceland so much power. There are some who think this attachment borders on religion. The test of this hypothesis is whether this phenomenon lasts past the lives of the generations who watched and listened to him. Will Graceland have the same pull for pilgrims two hundred years from now? Ted Harrison, in a book called Elvis People: the Cult of the King, says "Cults and new religions only form around a prophet or personality whose projected image and sustaining aura feeds a spiritual hunger."26 The future will decide that, but for now the pilgrimage to Graceland is traveled by believers.

"For Vietnam veterans, coming home from Vietnam was not the way John Wayne

had promised. You weren't a hero."27

The Vietnam War was a convoluted mess for America. Starting in 1954 we had

propped up one unpopular regime after another in South Vietnam trying to stave

off a Communist takeover by North Vietnam. We were told about the domino theory,

that great idea that if we let South Vietnam fall then all of Southeast Asia

would also become Communist. In the Cold War years of the 1950's and 60's,

this theory had power. And so we went from supporting to controlling these

dictators we had set up, and from advising their military to doing the

fighting ourselves. After the Gulf of Tonkin incident, or non-incident,

President Johnson got the Congress to allow him the power to prosecute

the war. America started bombing the North as well as the South. We increased

troop strength in the South to over 500,000 soldiers. We fought, killed,

died and suffered for ten more years before, finally, in 1975 it was over.

28

28

But that is not all that happened around this war. The Vietnam War was like no other conflict in our history. It turned father against son, brother against brother. It created the greatest anti-war movement in our nation's history. And it engendered recriminations among all of us who lived through it. One of the most ostracized groups of this period was the soldiers who had fought in this awful conflict. They were called baby killers and murderers. They were sons and brothers, fathers and sisters; regular people thrown into chaos and trying to survive. The war cracked the foundation of America. In the aftermath of this war the veterans were ignored. Silence was our way to try to forget all the pain and anger that surrounded this war. "Homecoming for vets, dead or alive, was mostly lonely. Few people had noticed when you left, and fewer expressed interest when you returned. Vietnam was on the newspaper front pages, yet somehow it was dirty, best left alone."29

30

30

In early 1979 the concept of a Vietnam veteran's memorial grew in the mind

of Jan Scruggs. He was a grunt, a rifleman, a soldier who thought that the

ones who were lost needed to be remembered. He brought it up at a veterans

meeting and was dismissed by all there except Bob Doubek. The dreamers had

doubled. One of the most important reasons for the memorial was the sense that

the country needed to reconcile its conflicted opinions about this war. The

veterans who were pushing the idea understood this. Senator George McGovern

was an early backer of the idea. His name was a lightening rod for many who

blamed the loss of the war on the anti-war movement and McGovern's presidential

race. They demanded his removal from the list of supporters. The organizers,

understanding of the need for reconciliation, refused. Letters poured in from

a mass mailing asking for donations. These letters detailed the hurt and division

in the country. "Letters that opposed the memorial showed as much pain

as those who supported it. A growing sense of just how deeply this pain ran

through America kept the vets who were working for the Fund going through eleven-hour

days and six-day workweeks."31 They believed, and others began to believe

also. People said it couldn't happen, not in bureaucratic Washington, D.C.

But first one Senator then another, one powerful bloc then another were persuaded

and the miracle became a reality. The Vietnam Wall was designed by a twenty

year old Harvard student named Maya Lin. Her design was chosen in a blind competition

over other more famous architects. "I never expected it to be passionless,"

Maya Lin explained to reporters. "The piece was built as a very psychological

memorial. It's not meant to be cheerful or happy, but to bring out in people

the realization of loss and a cathartic healing process." 32 The Vietnam

Veterans Memorial was dedicated on November 11, 1982.

And so the Vietnam

Wall as it is known became a shrine to the over 58,000 men and women who

lost their lives in Vietnam. It became a shrine where people could go and

remember. And people came. And they sat and cried and relived and remembered.

'I will be in Washington for the dedication, one vet wrote, I will not be

there to tell tales of terror in the skies over Hanoi. I won't be representing

anyone but a handful of ghosts whose blurry names and strangely boyish faces

needed to be welcomed home."33 The Wall allows many to face

and lay down some powerful feelings. It is, I believe, one of the most compelling

shrines in America for this generation.

34

34

There are many

things left by the people who visit the memorial. Many write letters to those

they lost, or leave personal items that connect them to their lost loved

one. These items are collected and stored by the National Park Service. They

are a moving tribute to the emotion that the memorial evokes. "I

share this with those of you who come to this hallowed wall of names-remembering,

seeking comfort and solace for the losses we all suffered as a result of Vietnam.

Know that others share your sorrow and pray for you and those you know and

love who are named here forever on this starkly beautiful memorial."35

As all pilgrimage shrines do, this memorial brings out the best, most honest

part of us. For those who had loved ones die, there is a strong emotional connection.

For those who fought against the war it brings sadness and confirmation to

the fight they waged. And for those who were too young to remember it shows

the reality of war and what it costs in human terms. "To me it means America.

To see all those names, all the dead boys, or kids. I was only nineteen when

I went over there. I got here the first time, I just sat down and cried, we

all cried and we held each other, them old beer-bellied dudes. I'm proud of

them. All those dead boys. I feel that by seeing their names in granite I can

lay some of the ghosts."36

This Memorial is different than other memorials

to other wars and the soldiers who fought in them. I feel the starkness of

the black granite wall diving into the earth says more about what this war

did to us as a country than other shrines do. I know that Normandy had great

emotion for all those who fought there, and I have seen all the crosses lined

up there. There is a great sense of the sacrifice they made to fight that war.

Maybe it is because the Vietnam War was my generation's war that gives the

Wall its power to me. No matter what group is honored by whichever memorial

there is, the important thing for me is to not let them be forgotten. When

we forget what war costs we are more likely to repeat our errors and rush too

quickly into another costly adventure.

Pilgrims set out on their journeys for many reasons and with many hopes. For

most the pilgrimage itself is as important and life-changing as the destination

they seek. Ellis Island, Graceland and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial all evoke

different spiritual or emotional feelings. They all connect us to a deeper

part of ourselves and they all have the power to also connect us with others

in a profound way. "In the end, pilgrimage is about discovery, both spiritual

and personal. While the sites we gravitate toward may be different, and our

chosen experiences will vary greatly, the core objective of all pilgrimage

experience is always transformational."37

Works Cited:

Coan, Peter Morton. Ellis Island Interviews: In Their Own Words. Facts on File. N.Y. 1997.

Cousineau, Phil. The Art of Pilgrimage. Conari Press. Berkeley. 1998.

Evans, Mike, ed. Graceland: The Legacy of Elvis Presley. Collins Pub. San Francisco. 1993.

Harrison, Ted. Elvis People, The Cult of the King. Fount Paperbacks. London. 1992.

Hine, Lewis. America and Lewis Hine, Photographs 1904-1940. Aperture Foundation. 1977.

Mahoney, Rosemary. The Singular Pilgrim: Travels on Sacred Ground. Houghton, Mifflin Co. N.Y. 2003.

Marcus, Griel. Dead Elvis. Doubleday. N.Y. 1991.

Mullins, Edwin. The Pilgrimage to Santiago. Interlink Books. Northampton,Ma. 2001.

Ogilbee, Mark and Reiss, Jana. American Pilgrimage. Paraclete Press. Brewster, Ma. 1998.

Palmer, Laura. Shrapnel in the Heart: Letters and Remembrances from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Random House. N.Y. 1987.

Reeves, Pamela. Ellis Island: Gateway to the American Dream. Michael Friedman Pub. Group Inc. N.Y. 1991.

Sandler, Martin. Island of Hope: The Story of Ellis Island and the Journey to America. Scholastic. N.Y. 2004.

Scruggs, Jan and Swerdlow, Joel. To Heal a Nation: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Harper and Row. N.Y> 1985.

Spencer, Duncan and Wolf, Lloyd. Facing the Wall: Americans at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Macmillan. N.Y. 1986.

1 Edwin Mullins. The Pilgrimage to Santiago. Interlink Books. Northampton,Ma.

2001. Page 62.

2Phil Cousineau. The Art of Pilgrimage. Conari Press. Berkeley. 1998. Page

xxiii.

3 Cousineau,14.

4 Cousineau,228.

5 Mark Ogilbee, and Jana Reiss. American Pilgrimage. Paraclete Press. Brewster,

Ma. 1998. Page xix.

6 Ogilbee, xii.

7 Ogilbee, xvii.

8 Mark Sandler. Island of Hope.: The Story of Ellis Island and the Journey

to America.Scholastic. N.Y. 2004.

9 Sandler, 11.

10 Sandler, 25.

11 Lewis Hine. America and Lewis Hine, Photographs 1904-1940. Aperture Foundation.

1977. Page 124.

12 Peter Morton Coan . Ellis Island Interviews: In Their Own Words. Facts on File. N.Y. 1997. Page 49.

13 Coan, 49.

14 Hine, 98.

15 Pamela Reeves. Ellis Island:Gateway to the American Dream. M. Friedman Pub.

Group Inc. N.Y. 1991. Page 69.

16Coan, 326.

17 Coan, 79.

18 Ogilbee. 21.

19Mike Evans, ed. Graceland: The Legacy of Elvis Presley. Collins Pub. San

Francisco. 1993. Page 28.

20Griel Marcus. Dead Elvis. Doubleday. N.Y. 1991. Page 5.

21 Evans, 69.

22 Marcus, 129.

23Ted Harrison. Elvis People, The Cult of the King. Fount Paperbacks. London.

1992. Page 59.

24 Evans, 148.

25 Ogilbee, 159.

26 Harrison, 11.

27 Jan Scruggs, and Joel Swerdlow. To Heal a Nation: The Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Harper and Row. N.Y. 1985. Page 11.

28 Scguggs, front page.

29 Scruggs, 141.

30 Scruggs, photo insert.

31 Scruggs. 28.

32 Scruggs. 147.

33 Scruggs, 139.

34 Scruggs, photo insert.

35 Laura Palmer. Shrapnel in the Heart: Letters and Remembrances from the Vietnam

Veterans Memorial. Random House. N.Y. 1987. Page 35.

36 Duncan Spencer, and Lloyd Wolf. Facing the Wall: Americans at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Macmillan. N.Y. 1986. Page 17.

37 Ogilbee, xx-xxi.

?