Parts

1, 2, & 3

by Karin MacDonald-Schmidt

Preface

In the study of America's national groups one must, first of all, turn one's attention to the past of the people who crossed the sea, for whatever habit patterns and mental traits a national group displays have been centuries in the forming. There is uniqueness about each immigrant group, a particular set of circumstances, a certain kind of cultural background that impel it to move, to think, and to live the way it does.[1]

You know a North Dakotan when you meet one; they make sure of it. Similarly, you know a Norwegian when you meet one. There is both rhyme and reason behind this. Nearly a third of present day North Dakotans are of direct Norwegian descent [2] . A greater number of people are likely some blend of German and Norwegian, but are raised with their Norwegian heritage in mind. People who have Norwegian relatives or are of Norwegian descent are trained from birth that this is of utmost importance in their lives. I am one of these people.

Norwegian

Immigrants on the way to the U.S. (Lovoll 25.)

My life has been shaped by the culture and heritage of Norwegian immigrants. Even in my name my Norwegian roots are evident; my father chose the Norwegian spelling of Karin instead of the English Karen so that I could better reflect my background. Much of my personality has been shaped by what is deemed important to my Norwegian/ North Dakotan family.

Family, church, and community are of chief importance in my life, just as they are for most descendents of Norwegian immigrants. For this reason the histories and lives of Norwegian immigrants interest me. As much as I already know about my own family I want to know about the other people with my heritage. It has been ingrained in my mind that you can never know enough about what you come from. The stories of homesteading families, of farmers, builders of towns and churches all hold a special intrigue. Some of the bravest men and women were those directly from Norway.

So many lives have been touched by this group of people; it

is not uncommon to cross the path of a person of Norwegian or North Dakotan

descent. The impact of Norwegian

Americans was able to spread throughout America; however in the Great Plains

this culture is perhaps best maintained.

North Dakota in particular is saturated with Norwegian culture.

Part 1: Who They Were

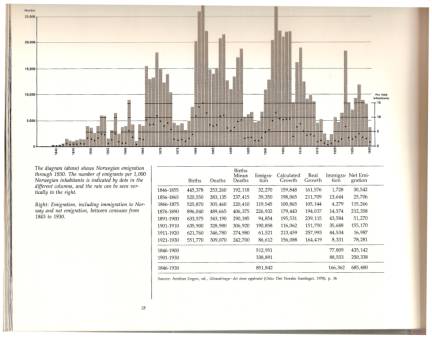

Graphic

timeline of Norwegian immigration to US. (Lovell 28.)

There were three great migrations from Norway, beginning in 1865 ending in 1920. These are also known as the first second and third waves of “the Great Exodus,” the three waves as a whole. [3] Over a period of just 55 years more than 550,000 people immigrated to America from Norway. The first, and smallest, wave moved 116,000 people between 1865 and 1875. The second was the largest: between 1876 and 1900 over 263,000 Norwegians came to America. Finally between 1901 and 1920 another 218,000 people relocated. [4] The third wave brought the highest number of Norwegian immigrants to North Dakota. There was still emigration to America after 1920, a small peak in the mid twenties, but the days of mass emigration seemed to be over for the Norwegians.

Never before or after has Norway seen such large numbers of emigration. This is partially due to Norway dissolving their union with Sweden, and the consequent raise in the economy. However, at the time, the birth rate in Norway was nearly double the death rate. Farms could not sustain all of the children. Parents found it difficult to maintain families on ever shrinking plots of land. As families grew there continued to be less and less land available for new farms. Norway has always had a rich farming heritage, even with only three percent of Norway under cultivation. [5] The emigrating Norwegians sought a land that could sustain such a life, and that would have room for future growth.

In the classic idea many Norwegians moved to America to gain freedom from the oppressive state religion. Norway also had a state church, a rigid structure that could not be doubted. While in Norway was united with Sweden and Denmark, many Swedish religious ideals had been pushed onto the Norwegian people. The right of the people to choose religion, or to vote for their royalty and republic leaders had long been absent in Norway. [6]

Norway had been losing its sense of country and self for nearly three centuries. At the turn of the 20th century a new group of Norwegian intellects went looking for the independent Norwegian culture. They found it in their farmers. For the simple minded farmer this was both an honor and an intense new pressure. Some stayed to bear their newfound cross; others opted for open air and America.

There was a different feel to the Great Exodus as a whole than in previous migrations: instead of the conquering desires of the Vikings “The immigrants came to America, not to conquer the country by force and to change its language and laws, but to find here greater freedom in religious, political and economic matters and better opportunities to make a living.” [7] Short of Ireland, Norway gave up the highest percentage of its population to the US immigration. [8] Over one million people emigrated from Norway to America in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

For many reasons the stoic people of Norway found their way to the United States. They formed communities and societies, churches, colleges, and towns. Norwegians made a new home for themselves where they seemed best to fit in.

As with most new immigrants, the first Norwegian settlement was in New York. It was called the Kendall Settlement, and was well known by Norwegian settlers as a stop on the journey west. After the completion of the Erie Canal, talk of a new perfect area for Norwegian settlement grew: the Fox River Settlement. Fox River sprang up overnight. News spread back home of the vast plots of land, and the great farming available in America, spurring the beginning of the Great Exodus. Soon Illinois began to fill, and the people moved North, Wisconsin was the next natural area and was quickly filled with Norwegians.

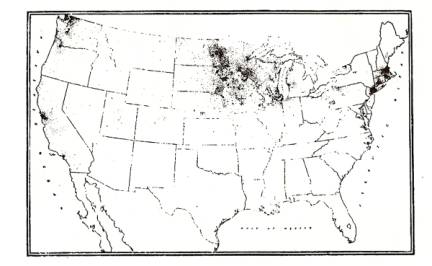

Norwegian

population shown in shaded regions (Norlie 83.)

Immigrants often came over in

groups. Which was one of the main

factors in the quick increase of dense Norwegian populations was the group

migration. Families traveled

together with friends and other people they knew. Traveling together made the idea of moving across the

Atlantic less intimidating; there was camaraderie and familiarity in the

journey. Not only did a group

migration make crossing the Atlantic less daunting, but it spread news back to

Norway more quickly. The more

people moving over, the more letters sent home. After the first Wisconsin settlements the move was on, the

Exodus had officially begun. Instead

of just single men coming over, whole families came: Grandparents, youths,

children, even single women. The

group structure of migration allowed for women to come with relatives, and

claim their own land.

Part 2: North Dakota Found

North Dakota is almost never at the top of the list when it comes to acclaim and populace. Many consider the movement to North Dakota to have “occurred more from necessity than choice.” [9] Some of the first North Dakotan settlers were actually of Scottish descent, but after gaining profit and success, most moved on, leaving North Dakota once again vacant of immigrants. The only inhabitants were the Native Americans that had already been forced onto reservations in the area, or pushed in from surrounding areas in the East and South. In 1878 only 28 people had registered a claim in North Dakota.

But soon the hearty Norwegians heard of the territory; both from the Scots, and from other travelers. After leaving the rocky hillsides, and unusable land of Norway, cold winters were less daunting to the Norwegian immigrants than to other groups. Between 1898 and 1919 over 250,000 people moved to North Dakota. They strayed from the typical course, which was close to the railroads, and spread throughout the state. [10] Ads were sent back home:

Profitable Farming

Fertile land at reasonable prices, a mild and healthful climate, crops of excellent quality and markets for them, and transportation facilities, are some of the advantages of the new country along the Pacific Coast Railway. There are splendid opportunities along this new line in the Dakotas…” [11]

At the turn of the century there was a change. With each wave of the Exodus the Norwegians drove further west. The third wave brought the Norwegians to North Dakota. Everyone had the itch for land. Plots were sold in sizes that ranged between 40 acres and 200 acres, the average being 160 (a quarter of a section.). [12]

The people who moved west were some of the most ambitious and hearty immigrants ever given to the United States. “Norway has never sent her criminals or paupers to America… She has given to America a goodly share of the strongest and most ambitious young men and women that she has been able to foster.” [13] After living in Norway these strong men and women were able to handle the unpredictable weather, and devastating winters better than many other groups of people.

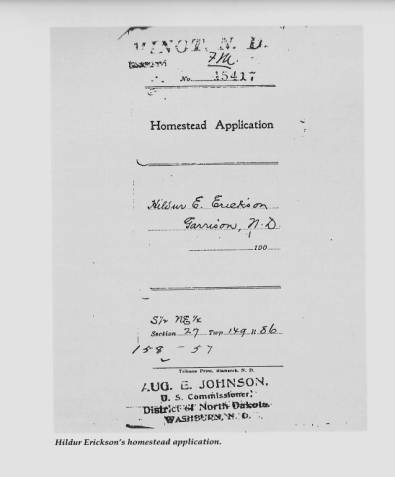

Typical

Homestead Application (Lindgren 59.)

Upon arriving on their homesteads they set up a shack, often no more than a 12 by 12 room set on a flat part of land. Some of the shacks were made from sod; others were made of simple scrap wood. The shacks had no running water or toilet, no heat or air. Women and children brought water from wells, and stocked the fire for heat. “At best, it was a temporary home, a place to stay while getting settled and proving up.” [14]

People often built their shacks on the corner of their lots, near to the shacks of others. Population was scant, but community was always important to the Norwegians. Building the shacks close together made it feel more like a neighborhood, and provided a little extra security on the homesteads. Even so, the Norwegians showed “little tendency to localize, and while predominant in many communities they manifest[ed] no aversion to settling where other groups [were] already represented.” [15] The Norwegians, while seeking familiar land, were not afraid to move into new territory, with different ethnic backgrounds. This is one of the reasons for the deep Norwegian influence in North Dakota.

Sod Shack,

and scrap wood shack(Lindgren 87.)

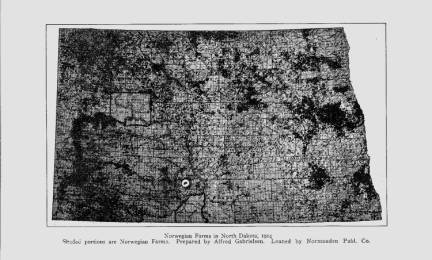

Although the greatest concentration of Norwegian heritage is in the Northern and Eastern parts of the state, there are still many Norwegians spread throughout. People didn't feel the need to gather because of ethnicity, they simply sought community. In the town of Ashley, there is a strong Norwegian influence even though only around ten percent of the original immigrants were Norwegian.

If there was a gathering of Norwegians in the Western or Southern parts of the state, they were often family, or had come over together. “Sisters and mothers moved to where their brothers and sons had found good land.” [16] The Norwegians gathered often and were fond of celebration, but never excluded others from the area. By sharing their culture with others it was accepted, and often adopted. Norwegians created a center of community which other groups were attracted to.

(Norlie 238.)

“North Dakota… experienced a settlement history slightly different from that of the rest of the country… The state was settled by a higher number of immigrants.” [17] All of the immigrants that settled in North Dakota had similar experiences; because they were all new to the country. They were all in a new place and had to adapt to a new setting, a new culture, and a new language. These people were open to other groups out of necessity to close themselves to other groups was to close themselves to most of the population. This lent itself to a melding of cultures and people, not often seen in other areas of the country. People found ways to be united, through faith, through hardship, through common problems instead of using these things to exclude one another, they bonded.

Part 3: The People and the

Progress

“There was always something going on, the women were always throwing dances, everyone went to the dances.” [18]

The Norwegian immigrants created a unique sense of community. It was vital to people that there was celebration and that there were events of kinship. The Norwegians were strong on family, tradition, fun, and religion. Without any of these elements they would not have been the people they were, nor would they have continued on to be the people they are today.

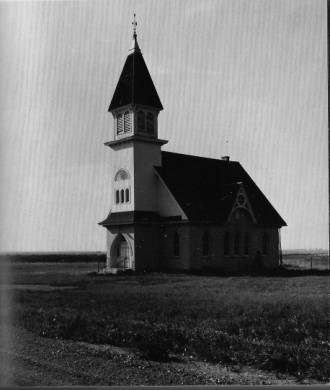

Typical Lutheran Church in

North Dakota (Photograph David Plowden)

One of the strongest associations for Norwegian people is the Lutheran church. Almost all of the Norwegian immigrants attended a Lutheran church or considered themselves Lutheran. “By and large, there was in the Norwegian immigrants an inbred desire to worship in the Lutheran way.” [19] Even those who left Norway to escape the pressure of a state religion found themselves caught up in the church and its frequent activities. Throughout the history of the state the Lutherans have played a large role. In New Salem North Dakota there was “a fairly large number of Jewish people, but there was no synagogue. The Jews all went to the Lutheran church.” [20]

Women ran most of the activities of the church. Aside from taking care of their families and tending theirs garden working in the church was their largest role. [21] Women used the church to maintain their status in the community. By participating in the church they involved themselves in every part of society. Newcomers visited the church for advice and friendship. Young couples came to church to solidify their relationship. Children were brought to church to learn the Bible. Men came to pray for crops. The old timers came to pray for salvation. It was central to the society. The church was often the largest gathering place, and more often still, it was a place of comfort and warmth.

The Lutheran church evolved as the people evolved. In the late 1800's there were three major branches of Lutheranism in North Dakota: the Norwegian Synod, the United Norwegian Lutheran Church, and the Hauge Synod. When the three finally joined together on June 9, 1917 they formed the Norwegian Lutheran Church of America. [22] It became one of the most powerful forces in North Dakota. For example, in the presidential election of 1928 “Hoover won handily with the support of Lutheran Norwegians.” [23] In 1915 the Lutheran church had over 72,026 members, more than triple the Methodist, Presbyterian, Baptist and Episcopal churches combined. [24]

This joint religious consciousness was one of the key factors in influencing the general culture of North Dakota. Even though there were just as many Germans in North Dakota, the Norwegian influence is decidedly stronger. Many of the Germans were already Lutheran, and those who were soon to convert. Often the Norwegians had the better established churches which the Lutheran Germans could attend. The Norwegian-run churches incorporated traditions from their homeland, and often included some of the language as well.

A common religious bond and the camaraderie this created often carried into gatherings outside of the church. “The Norwegians always seemed to get along better than the Germans.” [25] In families the Norwegians were a fun-loving people, interested in festivities. Nearly every town in North Dakota has a yearly fair, celebrating the individuality of the town. In New Salem they celebrate dairy farming, in Ashley wheat; in Minot they celebrate the several different ethnicities of the area.

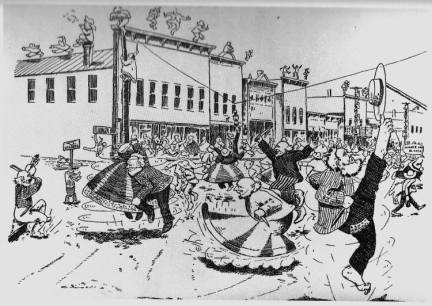

Cartoon of a

Norwegian-American Dance (Lovoll 187.)

Language was also affected by the Norwegians. It is more common to hear a Norwegian term in North Dakota than a German one, even though both groups have equal representation in most communities. Consider Uff-Da, it is comparable to scheisse, but much, much more commonly used (though you will probably hear the English term just as frequently, if not more often).

The Norwegians were quick to learn English. Most families “never spoke Norwegian at home, unless there were friends over who didn't want to speak English.” [26] This being said, there were definitely sprinklings of Norwegian in the language. It was frequent to hear people say “Tak for Mat” after a meal, meaning thank you for the food. Many of the States largest papers were printed in Norwegian. Most of the papers used a combination of Norwegian and English instead of staying pure to one or the other.

An assortment of

Norwegian-American Newspapers (Lovoll 117.)

One of the most obvious symbols of Norwegian influence is the telling Midwest accent. Consider that “ja” in Norwegian means “yes” in English, it simply translated to “ya”, a word that begins many sentences in North Dakota.

The hardworking and humble attitude of the Norwegian also translated in America. “North Dakotans are often accused of stubbornness… sometimes to the point of wrong-headedness. Their grandparents, who left one harsh environment for another… needed these qualities for survival on the prairies.” [27] Of the approximately 304 single women that had a homestead in North Dakota at least 123 were Norwegian. [28] It is common to see 20 men sitting on the frame of a house, taking a break from work.

From Nothing to do But Stay

“It has always been incredible to me how fast my parents built up their farm, by their own sweat and paying for everything in cash from crops that were good one year and bad the next. By the time I, their sixth child, came along nine years later, they had established a farmstead that included a one-and-a-half storied house, a barn, a 375 foot drilled well with a windmill, a two-storied granary, a chicken house, a hog pen, a blacksmith shop, a garage, two windbreak groves of cottonwood trees, and miles of barbed wire fence. Their farm equipment included three teams of draft horses, a plow, drill, harrow, mower, rake, binder, two hay wagons, a lumber wagon, a box sled, a cream separator, and a Model T touring car. They milked a dozen cows, fed out a dozen steers and hogs, and kept two hundred chickens. Much of those nine years my mother was pregnant.” [29]

The Norwegians were known for accomplishing great amounts of work a small amount of time. Parents educated their children, but still taught them the value of work, often putting them to work on the farm. Even today the driving age in North Dakota is only fourteen, so that children of farmers can work on the farm. With only three “months” (July, August, and winter) it is necessary for the North Dakotans to be on top of farm work at all times.

North Dakota has a proud farming and dairy heritage. In New Salem North Dakota stands the largest cow in the world: Salem Sue, a Holstein weighing over seven tons. The people of North Dakota are proud of their roots; they are farmers, dairymen, and townspeople. The people are simple, satisfied with hard days and a simple, but good, life. “If the farm can feed all of the children, why look somewhere else for food?” [30] Many of the people living in North Dakota have lived there all their lives, and are descendents of Norwegian immigrants.

Closure

Growing up I heard about the amazing woman my great-grandmother was. It was a requirement of being family to know the whole family history. Even though I didn't grow up in North Dakota, I know most everything there is to know about the state. I even get an accent when I visit the family farm. I was raised “thinking like a Norwegian.” [31] Even though there are other ethnicities in my heritage, none of them matter in comparison to my Norge roots.

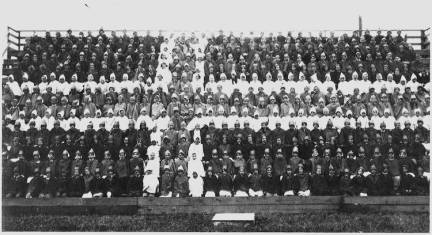

People forming the Norwegian

Flag (Lovoll 195.)

Norwegians are not only proud of their heritage but they like to flaunt it. If you take a trip to Ballard, where there is a large Scandinavian population, in Seattle you might be surprised to hear a few different accents, or see an abnormal number of trolls. There are several Norwegian flags flying high. Pride in North Dakota is decidedly more subtle. The Midwest accent displays their roots. People eat Lutefisk on Christmas, and make Lefse for all the holidays. There are four meals in North Dakota: breakfast, lunch, dinner, and supper. The people are kind and the day is simple. Instead of showing off their heritage, it is simply a part of daily life.

North Dakotans are well aware of their heritage, Norge or not, but I can almost guarantee you that every Norge you meet can tell you not only where their great-grandparents came from, but where in North Dakota, or throughout the country in general, their present day relatives live. Most families are wide ranging, for this reason I personally vowed not to marry someone from North Dakota for fear that we could be related. Family is of utmost importance; their history is of utmost importance. There is no other region like North Dakota; even South Dakota is more commercial with higher tourism and industry. The people rely on heritage and community for their sense of self.

Growing up I learned about when my relatives came over. I knew that my cousin was integral in the building of Salem Sue. I had seen my cousin Forest's museum: which was dedicated to our family. I saw the gravestones of my relatives, and the farms where my grandparents were born. Without being Norge I wouldn't be a whole person, my heritage describes me. North Dakota shapes the lives of its occupants; there is no avoiding the history, no avoiding the community, nor is there any desire to. You may live three miles from your nearest neighbor, but you know their life as well as your own.

“A thumbnail sketch of the ‘typical' Norwegian American of the mid-nineteenth century would look something like this: He… moves with unhurried precision… His eyes [hold]… no guile in them; rather early in life fine wrinkles appear at the outer corners or his eyes… Intensely loyal to the Lutheran Church and the Republican Party, he is a great respecter of authority in all forms; yet he is somewhat contentious and doesn't allow himself to be led around by the nose. He runs his affairs in an orderly fashion and when he undertakes something sees it to a finish… His thought, innocent of all subtlety, plows as carefully to the point as he himself to the next corner of his 40-acre plot… What he gets out of life he expects to get through his own efforts. He perceives clearly the details of his world and knows how to handle them… His is a small-scale life, the peasant and artisan mind that gets its satisfaction from doing a job well, not demanding spectacular returns for its efforts.” [32]

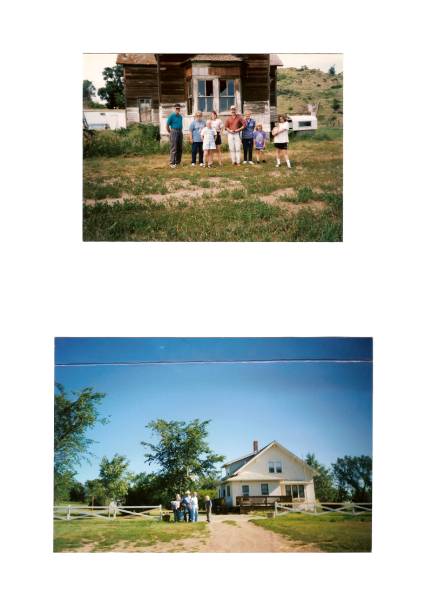

Above: the Anderson farm built 1886 Below: the Hoiby farm

built 1904

Above and Below: My North

Dakota

Works Cited

Bergmann, Leola Nelson Louis Adamic, ed. Americans From Norway, New York: Lippincott, 1950, 1970

Hampsten,

Elizabeth. Settlers' Children.

London: Oklahoma Press 1991

Hoiby, Gloria. Telephone interview, 22 Feb 2007.

Lindgrin, H. Elaine Land In Her Own Name, Fargo: North Dakota

State University, 1991

Lovoll, Odd S. The Promise of America: A History

of the Norwegian

American People. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1985

Norlie,

Olaf Morgan History of the Norwegian People in America.

New York: Haskell, 1973

“North

Dakota.” Infoplease. 22 February 2007.

http://www.geocities.com/researchguide/8firstfo.html

Schmidt, Clayton. Telephone Interview, 22 February

2007

Schmidt, Edna, Telephone Interview, 22 February 2007

Wilkins, Robert P and Wynona H, North

Dakota: a

Bicentennial History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1977

Works Progress Association,

North Dakota: A guide to the Northern

Prairie State 3rd edition. New York: Oxford University Press

1973.

World's Events, June 1908.