Hey, Mom, Look What I Made!

by Kate Robinson

The question "What is art?" can potentially incite a riot in circles of those who proclaim superior taste. Some would argue that true art requires a level of skill and aesthetics above the reach of most common people, but that excludes a myriad of creations that people put out into the world. A picture painstakingly drawn on construction paper by a young child for his mother is art worthy of a spot on the fridge, or maybe even a frame on the wall, but is it "art?" If it is not "art," then what is? And who, exactly, decides what is and what is not "art?" So the debate goes on and on. In 1972 French artist Jean Dubuffet coined the term "art brut" to describe the art of a different group and to criticize the narrow view of artistic integrity. "Those works created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses - where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere - are, because of these very facts, more precious than the productions of professions. After a certain familiarity with these flourishings of an exalted feverishness, lived so fully and so intensely by their authors, we cannot avoid the feeling that in relation to these works, cultural art in its entirety appears to be the game of a futile society, a fallacious parade."1

The term "outsider art" is an Americanized version of this term that has come to be used to describe anything from tattoos to homemade mailboxes, from the paintings of Grandma Moses to graffiti on subway cars. What exactly makes an artist an artist? And for that matter, how does one's historical context, given his or her status as "outsider," contribute to artistic expression?

Advocates of Outsider Art such as Lyle Rexer see in the great works of these artists "the same visual authority as work by the best artists I know. This "outsider" work shared something essential with great mainstream, or "insider" work. It issued out of deep necessity and embodied the full formal capacities of a distinctive visual imagination."2 Here Rexer gets to the heart of what seems to compel the three artists that will be here discussed to create. Their firm placement as "outsiders" in the world around them, let alone the world of "art," gives them a struggle to express artistically.

Daniel Johnston's

struggle with bi-polar disorder pushes him into the struggle of good vs.

evil and for social acceptance that he expresses in his art. Henry Darger's

negative experiences as a child instilled a lifelong concern for the welfare

of children, which comes through in his work. And Judith Scott's patiently

wrapped cocoons seem to symbolize her enduring search for comfort and security

in an institutionalized life. The aspects of these personalities that make

them outsiders also make them artists, and in their art there is a definite

voice of the oppressed. Sometimes it is the artist's own voice, and sometimes

he is speaking on behalf of someone else, but in either case the statements

made by the works they have produced should be listened to more carefully.

These three artists each come from a different historical context, and the

different ways in which the public, their families, and the institutions

they dealt with responded to them either encouraged or hindered their expression

as artists, and in some cases you could argue that they have been exploited

by all these different factors. Here we will explore what makes them tick,

as well as how their space and time has shaped them as "outsider artists."

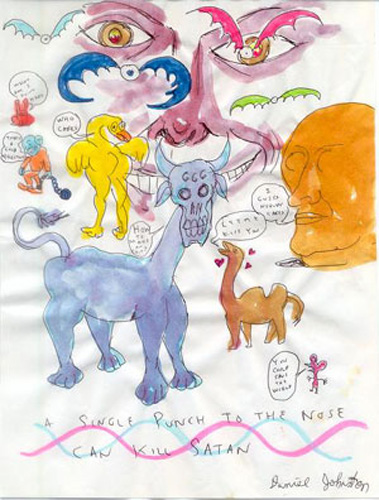

Johnston, Daniel. A Single Punch To the Nose Can Kill Satan. Artist's own collection, Waller, TX.

As a reclusive teenager growing up in the panhandle of West Virginia Daniel Johnston showed great creativity, making short super 8 films with his friends, recording stories, thoughts and Beatles-inspired songs on cassette tapes, and making cartoon drawings. In the eyes of his fundamentalist Christian family though, Daniel's fantastical dreamings were impractical and in no way prepared him for "real life." So Daniel left his family and joined a carnival. He wandered around and eventually found refuge in Austin, Texas where he began recording tape after tape of his lo-fi earnest songs to pass out to friends, journalists, anyone who would take them. After awhile he started to create a fan-base, and people started to recognize his name around town. When in the 80's Austin's music scene started to get wider recognition Johnston managed to get a spot in a spring break commercial on MTV that gave him a tiny taste of a fleeting celebrity.

While Johnston was gaining more and more popularity in the independent music world, his on-going struggle with bi-polar disorder became more and more apparent in both his craft and his day-to-day life. The very evening that he appeared on MTV in 1986 he was in the Austin State Hospital having been committed for attacking his manager at his job in McDonalds. A bad LSD trip had triggered Daniel's violent mood swings. Johnston's struggle with mental illness has produced a huge catalog of heartfelt and surprisingly insightful songs about the human condition. His ability to use imagery is uncanny, and while upon first listen the songs may sound awkward or even un-listenable, when one listens closer the lo-fi recording style and the cracking, sometimes off-key singing adds immensely to the emotion and imagery of the songs. A running theme in both Daniel's drawing and music is that of good vs. evil or Daniel vs. Satan.

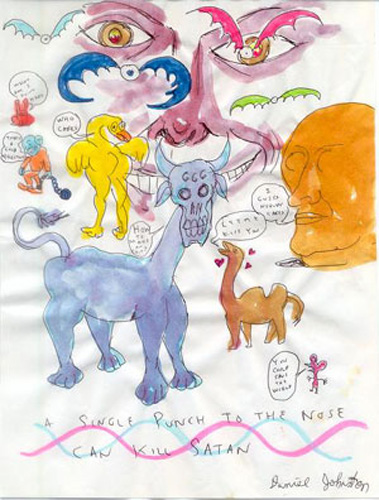

Johnston, Daniel. Symbolical Visions. Artist's own collection, Waller, TX.

In this drawing the fight between good and evil is apparent, notice the boxing gloves on the half skulled Boxer and the "Vile Corrupt." The Boxer, with the light pouring out of his skull is found in many of Daniel's drawings, and it is said to be a sort of alter ego, an idealized version of himself fighting for the cause of righteousness. The opened light-pouring skull can be seen as a halo of sorts, further emphasizing his righteousness. The drawing is also riddled with Christian imagery; the fish under his signature is something he frequently uses in conjunction with his name, as if to remind the viewer of the position from which he is coming.

His mood swings and obsession with good and evil have also produced many harrowing stories such as the one his father tearfully tells in The Devil and Daniel Johnston, a documentary film made about his life in 2005. While taking a leisurely afternoon flight in his father's small engine plane Daniel flew into a fit about the devil. Daniel removed the keys from the ignition while in flight and threw them out the window. Luckily his father, a flying enthusiast for many years, was able to land the craft without harm to either of them, but even a violent crash into a tree could not show Daniel the error in his decision. Everyone was safe, and Daniel was sure that it was because of his heroic act. In his mind, had he not thrown the keys out the window something truly tragic would have happened.

In Daniel's song "Devil Town" he sings "I was livin' in a devil town/didn't know it was a devil town/ohhhh Lord it really brings me down/about the devil town." This simple song, sung in Daniel's signature shaky, off-key voice captures the desperation and lack of control and acceptance that Daniel seems to toil with regularly. In the next verse he sings "All my friends were vampires/didn't know they were vampires/ turns out I was a vampire myself/in the devil town,"3 which brings to light another major theme of Johnston's work. His emotional drawings and songs show an internal battle against evil, but they also show the heart of a man who feels like he has no control over his situation and who seems to feel disconnected even from himself. In "Go" Daniel implores the listener to "Go, go, go, you restless soul, you gonna find it"4 and one gets the sense that he knows this from his own experience. He had to get away from his family to do what he wanted to with his own life, and he wants to help his listeners to do whatever it is they need to do to find their own fulfillment.

In any other time period Johnston most likely would have spent his entire life in and out of institutions, marginalized and thought of as someone with nothing to contribute to society. Some may say that MTV and the musicians such as the members of Sonic Youth who brought Johnston to New York to record with them and then had to deal with his mental illness when he ran away and got lost in the city in a manic fit, were exploiting Johnston. You could also argue, as Daniel himself does, that that trip to New York was one of the highlights of his life, especially the time he spent wandering alone around Times Square as Sonic Youth frantically searched for him and puzzled over what they were going to tell his parents. The opportunities that have been made available to him given his historical place in the world have allowed him to live a rich and fulfilling life doing what he loves to do. While Johnston has spent some time institutionalized (a total of five years throughout his life), he's spent far less time in those hospitals than he most likely would have in 1915, or even 1960. Daniel's modern time period has allowed him to share his unique voice as a crusader for the cause of gentle humans against the evil of the world.

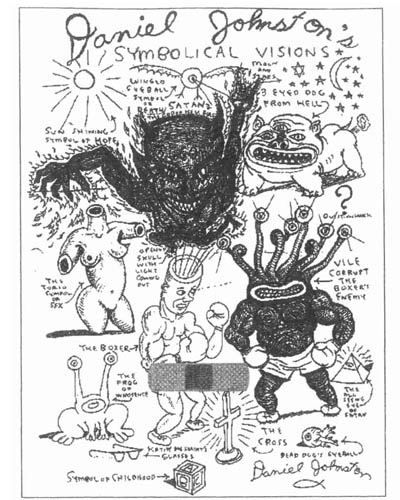

Darger, Henry. At Jennie Ritchie. Frye Art Museum, Seattle. On loan from American Folk Art Museum, New York.

Starkly contrasted with Daniel Johnston is outsider art darling Henry Darger. From 1930 until his death in 1973 Darger lived as a recluse on the North Side of Chicago and worked as a janitor. Born in 1892, he lost his mother when he was four years old. He was quite close to his father until they were separated in 1900 because the crippled Darger, Sr. was physically and financially unable to support either himself or Henry. His father was taken to a St. Augustine's Catholic Mission home and Henry went into a Catholic boy's home. He was institutionalized in 1905 after having been deemed by a doctor as "feeble-minded."5 He stayed in the institution being controlled with forced labor and other severe punishments because of both a Tourette Syndrome-like tendency to make odd, irritating noises and for his smart-aleck behavior which Darger himself attributed to his ability to see through the bullshit most of the adults in his life dealt out to him. After a series of unsuccessful attempts to escape, he finally succeeded in 1908. While in the institution Henry had learned of his father's 1905 death, so the 16 year-old had no one to turn to once he got out. He managed to find menial labor jobs around Chicago and supported himself thusly for the next fifty years.

Given his childhood it is not surprising that the adult Darger chose to live a life of essential solitude. While little of his life is really known, almost everything that has come to light about him is disputed! There has been no evidence found of him showing any interest or talent in art before his landlords discovered and found a plethora of quite beautiful writing, drawings, paintings, and collages shortly before his death in 1973. When Darger passed away later that year they took charge of his estate and sifted through the 15,000 page volume he had titled The Story of the Vivian Girls in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal of the Glandelinian War Storm or the Glandico-Abbienian War as Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion. What they discovered within its pages was a dream world wherein cruel men, beat, tied to trees and mutilated, and forced into labor, enslaved children. These themes most likely stemmed from his own experiences as a child. The book told the tale of the Vivian Girls, seven princesses of the land, and the Blengins, butterfly-winged, ram-horned, girls who both helped and hindered the children in their attempt to break free of their oppressors. The epic landscapes that Darger created are breathtaking, and while his limited drawing ability is apparent, his talent for composition, use of color, and drafting is remarkable. Along with the text and accompanying pictures his landlords found in his apartment pages and pages of tracings of newspaper ads, children's books, comics, and other ephemera which he obviously used to teach himself to draw the children, clouds, soldiers, and flowers present in his artwork. Along with drawing Darger employed watercolor and collage in his often double-sided landscapes. The repetition of certain characters appearing in the same work gives a signature to his unique style. Another curious signature is the anatomy of the female children he drew. Many of the girls are naked, and all of them have penises, suggesting that Darger very well may have never seen a naked woman or girl in his lifetime. Or maybe there is another reason for this anatomical anomaly, maybe the girls of his story are meant to encompass all children, including he.

Darger, Henry. Storm Brewing (detail). Frye Art Museum, Seattle. On loan from American Folk Art Museum, New York.

The protection of children was something Darger was incredibly concerned with in his lifetime, he discussed with a like-minded friend the potential creation of a "Children's Protective Society," and newspaper clippings found in his apartment suggest that the 1911 strangulation of a Chicago girl, Elsie Paroubek, might have prompted his undertaking of this great work.

There is no way of truly knowing when exactly Darger was creating this work. The bulk of the ads and such from which he drew were from the 40's and 50's, but given the great amount of time that he spent hidden away and the sheer volume of text one assumes that his work spanned decades. A lot happened in the United States in between 1930 and 1973, wars were fought, social movements were sparked, and both of these themes are very present in Darger's work. The historical impact that seems most influential, though, is still the experience he had as a difficult child. When one compares Darger to someone like Daniel Johnston, it is quite obvious where he was stifled by his historical context. In earlier human history the tendency of people to lock up anyone who thought outside of the box or challenged "normal" behavior was far greater than it is today. One can't help but wonder that if Henry Darger had been born in the time of Daniel Johnston, could he have also possibly, in his lifetime, found an audience for his artistic vision?

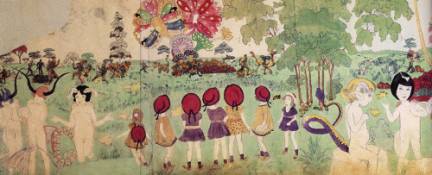

Judith Scott with one of her untitled works, 1998 photo: Leon Borensztein.

Judith Scott, unlike Daniel Johnston and Henry Darger, has had practically no say in the directions her life has taken. Judith was an unexpected twin, and at the time of her birth (1943) parents were encouraged to just give up their mentally handicapped offspring. Luckily for Judith she was able to spend the first seven years of her life with her family. Although she showed a marked difference in development, Judith's parents treated her just as they did her fraternal twin sister Joyce, dressing them alike and encouraging them both to participate in childhood experiences as equals. This allowed Judith to at least start off her life with a strong bond to her sister. When it came time to start school though, Judith was found to be "ineducable,"6 too difficult even to be in the class qualified for children with learning disabilities. At this time, October of 1950, she was sent to the Columbus State School, an institution for the mentally retarded. Her Clinical Record states that "She does not seem to be in good contact with her environment. She does not get along well with other children, is restless, eats messily, tears her clothing, and beats other children. Her presence on the ward is a disturbing influence."6 This may seem as though Judith was really a problem, but in reality it is a reflection upon the poor quality of her care in this facility. While her Downs Syndrome was apparent, it took almost thirty years for anyone to realize that Judith was also deaf.

In 1986 Joyce Scott, Judith's twin, a woman of above average intelligence who had lived a normal life in California for the thirty plus years that they'd been separated, had an epiphany and called for Judith to be sent to California to live under her care. Judith was put on a plane to San Francisco; having never flown before and not knowing where she was going at all, this was a terrifying experience for her. "Joyce remembers how, 'She arrived looking lost and terrified. There were dark rings under her eyes. She fell into my arms and sobbed. I am not sure she knew who I was. She was just glad to have someone there to look after her.'"7 Once in California, a state that guarantees the availability for ongoing education for the mentally retarded, Joyce enrolled her sister in the Creative Growth Art Center. For the first few months Judith showed little interest in creating and Joyce considered taking her out of the program, but when she started taking a fiber arts class with artist Sylvia Seventy, Judith began making sculptures in her own radically unique style. The concept is simple enough; she wrapped objects in yarn or string. Judith would wrap sticks, cardboard, things she found in the trash, objects stolen from her classmates or teachers, anything she could get her hands on, in pieces of yarn and string creating cocooned vessels. Judith's sculptures are oddly arresting, giving the viewer a feeling of a search for security and warmth. Having lived most of her life in a sterile institutional setting and given no options for really communicating with others one can understand where Judith may want to be wrapped in yarn herself. Or maybe she feels as though she already is, wrapped up in her disabilities and distinctly closed off from the larger world.

When Henry Darger

managed to escape his institutionalization he was completely alone, luckily

for Judith she had someone there who could help her to create a fulfilling

life for herself. Being born with Downs Syndrome in the time period in which

she was made Judith Scott "also the product of a still more limiting

and disturbing condition, the syndrome resulting from prolonged exposure to

the empty and manipulative existence characteristic of life in custodial institutions."7

The dormant bond that she had created as a child with her twin sister, though,

somehow revived in the mid-eighties, was Judith's saving grace. The actions

taken to further the quality of life of mentally retarded individuals with

documents such as Declaration on the Rights of Mentally Retarded Persons, created

in 1971, made it possible for a woman like Judith Scott to share her artistic

vision with the world. This declaration said, among other things, "The

mentally retarded person has a right to proper medical care and physical therapy

and to such education, training, rehabilitation and guidance as will enable

him to develop his ability and maximum potential."8 And the world is quite

thankful for it, "her pieces, including works exhibited in galleries in

SoHo and Chelsea in New York City this spring, have sold for up to $15,000."9

Scott, Judith. Untitled doll. Ricco Maresca Gallery, New York. Raw Vision 38 (May 2002): 40. Photo by Charles Brechtold.

The question of exploitation has been raised with Daniel Johnston, and in Judith Scott's case it must be raised again with more consideration. Judith did not speak, hear, read, or write; she was really in no way involved in the buying and selling of her art except in the money that she received from it, which is hardly close to the amount that other people made from it. "Gross sales from her art have come to $150,000 [in 2001], but with the 50 percent gallery commission and the art center's 50 percent cut of the remainder, she has made about $35,000, which is put in a trust."9 Does this qualify as exploitation? She is obviously consumed by her craft; almost as arresting as her finished piece is the process of stealing an object, and meticulously wrapping it in her corner at the Center for Creative Growth. She seems to have lived a contented life in a supported living home with 14 other disabled adults; according to the house supervisor, Judith only ever became upset was when she was kept home from the center for a doctor's or dentist's appointment.9 Is exploitation negated when the exploited lives happily unaware of it? This question could raise a huge debate, especially in the case of Judith Scott and other mentally handicapped people who have little control over their lives. Had she lived in an earlier time, or had her sister not saved her from institutionalization she would have died an anonymous inmate in isolation. Instead she has been allowed to live and work in an art world where she, along with plenty of others, can make money off of her beloved cocoons. Which would you rather?

After looking

at these three artists and their three very different situations one is left

with a unique view of what it means to be an outsider artist and the different

ways the outsider artist is encouraged by, hindered by, or even exploited

by his or her historical context. It seems, in fact, that their very status

as social "outsiders" compels them towards creating as "artists." Daniel

Johnston, Henry Darger, and Judith Scott each have given a unique artistic

vision to the world of art. Daniel envisions himself as a crusader against

the forces of good and evil that pervade over all of our lives. Similarly,

Henry could be seen of a champion of the cause of children oppressed in a world

built for adults. Judith's diligent wrapping gives her an outlet for expression

despite the limitations of her disabilities. This similar strain of fighting

against oppressive or detrimental forces seems to unite many outsider artists,

as well as many crusaders of American social history in the twentieth century.

Imagine if Darger had published his epic tome during his lifetime. What sort

of impact on the world of social change might it have had? He experienced in

his own life adult control and adult refusal to even try to understand his

childhood expression. The world could possibly learn a lot from the minds of

children if only they were given a voice and taken a little bit more seriously.

Works Cited

Anderson, Brooke Davis. Darger: the Henry Darger Collection at the American Folk Art Museum. New York: American Folk Art Museum/Harry N. Abrams, 2001.

"Daniel Johnston." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 13 Mar. 2007 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Johnston.

Darger, Henry. Henry Darger: Art and Selected Writings. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2000.

The Devil and Daniel Johnston. Dir. Jeff Feuerzeig. With Daniel Johnston, Jeff Tartakov, Bill and Mabel Johnston. Sony Home Video, 2006.

Dubuffet, Jean. "Place à l'incivisme." Art & Text 27 (1987): 36.

"Henry Darger." Wikipedia,

The Free Encyclopedia. 13 Mar. 2007

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Darger.

Johnston, Daniel. The Late Great Daniel Johnston: Discovered Covered: Disc 2: The Originals. Gammon Records, 2004.

Johnston, Daniel. Songs of Pain. Stress Records, 1987.

"Judith Scott." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 13 Mar. 2007 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Judith_Scott.

MacGregor, John M. "Metamorphosis." Raw Vision 38 (May 2002): 38-42.

MacGregor, John M. Henry Darger: In the Realms of the Unreal. New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 2002.

MacGregor, John. Metamorphosis: The Fiber Art of Judith Scott. Creative Growth Art Center: Hong Kong, 1999.

Nieves, Evelyn. "Artist Emerges With Works in 'Private Language.'" New York Times 25 Jun. 2001, natl. ed.: D1+

Rexer, Lyle. How to Look at Outsider Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2005.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Declaration on the Rights of Mentally Retarded Persons. States Members of the United Nations, General Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland, December 20, 1971.

1 Dubuffet, Jean. "Place à l'incivisme." Art & Text

27 (1987): 36.

2 Rexer, Lyle. How to Look at Outsider Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,

2005.

3 Johnston, Daniel. "Devil Town." The Late Great Daniel Johnston:

Discovered Covered: Disc 2: The Originals. Gammon Records, 2004.

4 Johnston, Daniel. "Go." The Late Great Daniel Johnston: Discovered Covered: Disc 2: The Originals. Gammon Records, 2004.

5 MacGregor, John M. Henry Darger: In the Realms of the Unreal. New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 2002.

6 MacGregor, John. Metamorphosis: The Fiber Art of Judith Scott. Creative Growth Art Center: Hong Kong, 1999.

7 MacGregor, John M. "Metamorphosis." Raw Vision 38 (May 2002): 38-42.

8 United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Declaration on the Rights of Mentally Retarded Persons. States Members of the United Nations, General Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland, December 20, 1971.

9 Nieves, Evelyn. "Artist Emerges With Works in 'Private Language.'" New York Times 25 Jun. 2001, natl. ed.: D1+.