v

The Color of Home

by Katherine Lansdowne

He was a black solider in the segregated United States military. After fighting a war for a freedom and democracy which had never been extended to him, Eugene Burnett returned to the states with over a million other Black GIs and started looking for a home to settle down in. "I went up to the salesman, we're interested in your home, we're interested in buying one, and, uh, what is the procedure? Is there an application to be filled out?" So forth. _So he looked at me. Looked around and he said to me. He says, "Listen, it's not me, but the owners of this development have not as yet decided to sell these homes to Negroes. [Mrs. Burnett] It was as though it wasn't real. You can't imagine - but for someone to come out and actually tell you that they can't sell to you - you know, I, I was really on a - oh, man look at this house! Can you imagine having this? And then for them to tell me because of the color of my skin I can't be a part of it?"i

As a veteran of World War II, Eugene was eligible for benefits provided by the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, otherwise known as the G.I. Bill, and should have had access to a federally backed home loan, but without a home to spend it on, what good did that do him?ii After fighting to protect freedom and democracy in a jim crow military, he had come back to live in a segregated nation.

This interview with the Burnetts tells a familiar story about young African American families that attempted to buy or rent homes in Levittown, a housing development which began on Long Island in New York in 1947. Levittown started by Abraham Levitt and his sons-William and Alfred.iii The development enjoyed a success so immediate that two days after the announcement of the Levitts' plans, fifty percent of the homes had already been rentediv. Levittown was a community built as commercial enterprise and, as such, the appeal to new customers was a driving force for its creators.

v

The Levitts felt that in order to continue to draw in the ideal customers- young, white, families, generally renters or purchasing on the G.I. bill; they had to prevent anyone of a different racial background from moving into the community. So, they decided not to allow non-white families to live in Levittown. It should be mentioned, however, that they did accept resident of Jewish background; who were not, at the time, considered to be members of the Caucasian race. This is presumably because the Levitt family was Jewish.

Despite a nationwide civil rights movement, and the enactment of Federal laws prohibiting segregation, the Levittown polices of racial discrimination continued. "The Negroes in America are trying to do in 400 years what the Jews in the world have not wholly accomplished in 600 years. As a Jew I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice.. But...I have come to know that if we sell one house to a Negro family, then 90 or 95 percent of our white customers will not buy into the community. This their attitude, not ours....As a company our position is simply this: We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem but we cannot combine the two" Levitt said in the early fifties.vi

And the way they solved that housing problem, was through the creation of racially restrictive housing covenants, which firmly prevented the arrival of any demographically undesirable members of society. These covenants were fully supported by the Federal Housing Administration, so fully in fact that the practice of using them was adopted as the appropriate solution to the real estate community's problems with societal mixing.

The Federal Housing Administration adopted a practice of color coding the most preferred, or homogeneously white, areas of a community and the more diverse, or less desirable, areas. White areas were coded as green, and the minority areas were coded red-this was the origin of a real estate practice that would come to be know as "redlining". In reaction to this method of quantifying property value, white residents along Eight Mile Road in Detroit, Michigan built a six foot wall to separate themselves from their black neighbors in a successful attempt to improve their FHA ratings and raise their property values. vii

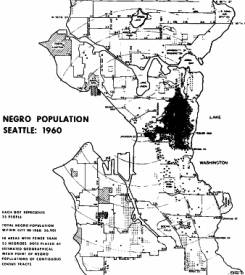

And right here in Seattle, most neighborhoods "north of the ship canal" were populated with the use of racially restrictive covenants. This passage from a 1928 housing contract in Ballard, references not just the sale to, but the mere presence of Jews, African-Americans, or Filipinos. "No part of said property hereby conveyed shall ever be used or occupied by any person of the Ethiopian, Malay, or any Asiatic race, and the grantee, his heirs, personal representatives or assigns, shall never place any such person in the possession or occupancy of said property, or any part thereof, nor permit the said property, or any part thereof, ever to be used or occupied by any such person, excepting only employees in the domestic service on the premises of persons qualifying hereunder as occupants and users and residing on the premises."viii

What motivated the property owners who used these covenants, was not just a desire that relationship between blacks and whites should remain far from neighborly, they had concerns of a financial nature as well. Real estate agents felt that inclusion of other races, specifically African-Americans, would not only lower property values through their presence alone, but that they would drive out the existing white homeowners.

ix

The Federal Housing Administration was strongly opposed to the idea of racial mixing. It feared that if "inharmonious racial or nationality groups" were allowed to occupy the same areas. it would result in a loss of property value. The FHA warned Americans about the dangers of a failing to maintain segregation. "If a neighborhood is to retain stability, it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied that the same social and racial classes,' the Underwriting Manual openly recommended 'subdivision regulations and suitable restrictive covenants' that would be 'superior to any mortgage." x

From 1934 to 1950, this prospective loss in property values covered the full scope of the FHA's interest in the position of race in housing matters. FHA Underwriting Manuals released in 1938 and 1947 did not specifically endorse the use of racial covenants, but the practices were still clearly condoned by action of not by written word. The restrictive covenants produced during this time banned an person of African descent from living on the property except as a domestic servant or laborer."xi

The deepest wound caused by these kinds of housing practices was not necessarily their immediate effect. An African-American family turned away from a purchasing their home of choice was humiliated and missed out on the benefits that community had to offer. But they also missed out on something much bigger-the future which came with that investment in a home.

If two families, one black and one white, both tried to buy homes at Levittown in 1947, and the black family was turned away, what would happen? The black family ends up renting a similar home in neighboring community. On the surface, their living conditions might seem comparable, even equal. However, the white family is building equity and increasing their net worth while the black family is remaining static. Over time, with the inflation of real estate prices growing faster than the general economy, this imbalance increases, eventually reaching a point where the two families are now in completely separate economic classes. The white family can now afford to send its children and grandchildren to college, passing on that financial advantage to future generations, a wealth gap that widens every year.

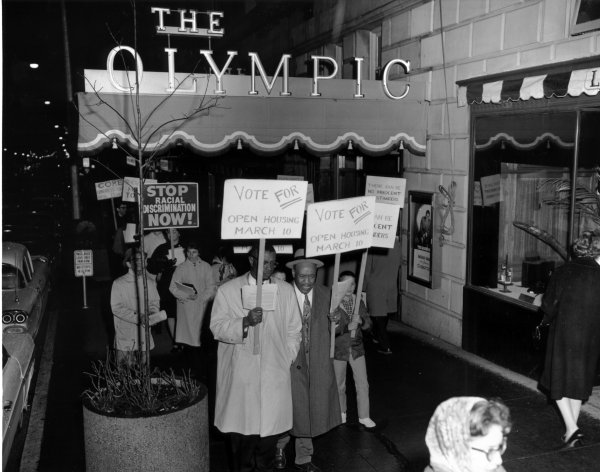

African Americans civil rights activists, often alongside whites, have fought to narrow that gap through protest, civil disobedience, and other efforts to change the unfair laws. In Seattle, in July 1963, a sit-in was held in the mayor's office to focus attention on anti-discrimination housing legislation, which had been languishing in inactivity for a year at that point. They were able to force the issue onto a ballot, but the vote was not scheduled until March of the following year. On March 10th1964, the fair housing ordinance was outvoted 115,627 to 54,448.

Despite this defeat, the anti-segregationist community in Seattle worked together to develop grassroot organizations like the Fair Housing List Service which provided avenues for racial minority buyers to locate sellers that were willing to work with them. These types of groups, in combination with the major Supreme court cases which were being won, helped to alter public opinion. Three weeks after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King JR, on April 19, 1968, the ordinance passed; making it illegal to discriminate based on racial or ethnic background. In 1975, this was expanded to include people of different gender, sexual orientation, marital status, or politics.

xii

On May 3, 1948 the Supreme Court case of Shelley v. Kraemer produced a landmark decision in the struggle for civil rights and fair housing. Although the court did not ban the use of all restrictive covenants, stating that private parties could enter into similar arrangements by choice, it was decided that these restrictions could not be legally enforced, as such an action would be considered a state action and would therefore be illegal under the fourteenth amendment.xiiixiv

In February of 1949, the FHA announced official changes in policy which banned the use of racially restrictive housing covenants. Or, more specifically, would withhold insurance (the main purpose of the FHA being to provide insurance for housing-related financial transactions) from agreements where such language existed. This change in course was celebrated in the press, although its limitations were clear from the start. For instance the policy would not go into effect for over a year, and many realtors in the southern states declared almost immediately that it had no bearing over them.xv

However, after a long civil rights struggle for fair housing practices, the practice of blatant and purposeful redlining has become widely seen as an unethical (not to mention highly illegal) practice. It lives on, however, as minorities continue to reside in the neighborhoods they have been assigned, and affluent white citizens designate the areas where the grass is greenest-using their money as a protective barrier.

The disparity in wealth between whites and blacks is still an active problem, despite the removal of government sanctions for these racist practices. One of the causes of this persistent inequality is that white Americans have always retained the largest percentage of the countries wealth. They are running off a head start so large that the minority populations have not had a chance to catch up yet. It has been estimated that up to eighty percent of a person's wealth accumulated over their lifetime originates as some form of gift from past generations of family. The wealthy breed more wealthy, making it difficult to close that gap.xvi

Because we shut out such a large percentage of our population at a time when so many families were out to buy up homes.; we set in motion the economic class distinctions, along racial lines, which we are reaping the consequences of today. The grandchildren of those families are butting up against the same barriers to wealth, and we have not yet created a way to climb over them.

It is important that racially prejudiced real estate practices not be supported by the government, but it most important that they not be supported by its citizens. The concept of redlining, or any form of property value assignment which accounts for racial demographics, would be useless as tool for segregation if the white community members didn't buy into them. Every time a white family moves for fear that their new black neighbors will reduce their net worth, they are making that fear a reality.

We have the opportunity to resist these newer and more subtle forms of segregation by being actively aware of the demographics of the places we call home. Move into a section of your town which is predominantly populated by people of a different race than yourself. Welcome diversity into your neighborhood. And, most especially, read the contracts associated with your property and refuse to accept any language which excludes another group of people.

i Race: The Power of an Illusion. California Newsreel. Videocassette. 2003.

ii GI Bill History (U.S. Department of Veteren's Affairs). 2007. <http://www.gibill.va.gov/GI_Bill_Info/history.htm>

iiiWikipedia; Levittown, New York <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levittown,_New_York>

iv Wikipedia: Levittown, New York.. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Levittown,_New_York>

v < http://www.sialis.org/images/levittown2.jpg>

vi page 141 Halberstam, David. The Fifties. New York: Villard Books, 1993

vii Race: The Power of an Illusion. California Newsreel. Videocassette. 2003.

viii Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. 2004-2006. James Gregory. <http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/>

ix < http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/segregated.htm>

x page 208 Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier. New York: Oxford University

Press, 1985

xipage 365 Note 54 Jackson, Kenneth T. Crabgrass Frontier. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1985.

xii < http://clerk.ci.seattle.wa.us/~public/doclibrary/OHousing/1964Mar2.shtml>

xiii Wikipedia; Shelley v. Kraemer<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shelley_v._Kraemer>

xivFindlaw.com "Shelley v. Kraemer" <http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=US&vol=334&invol=1>

xv Page 225-227 Vose, Clement E. Caucasians Only. Berkely, University of California

Press, 1959.

xvi The Nation.com. March 8, 2001. <http://www.thenation.com/doc/20010326/conley>