Drone? Clone? or SUPER-CITIZEN!

by Reuben Yancey

Would you like to go crazy? It's easy; just ask everyone you know to lie to you. Not all the time, just, let's say, half the time. Ask your friends and family to lie about your phone messages, how much gas is in the car, whose turn it is to wash the dishes, and even lie about how they feel about you. In no time at all you'll be certifiably insane.

Which is how many of us, myself included, would describe the condition of our

country and the world today. Poverty and wars, the lack of health care, the

creation of endless and wasteful consumer products while the environment is

being systematically degraded, all point to the inability of humanity to coherently

govern itself. If humanity were a single person they would be under the court

mandated care of mental health professionals (provided the funds were available,

otherwise they would be just another crazy homeless person).

Continuing this metaphor let us further imagine that this crazy person called "humanity" is

hearing voices in their head telling them to do stupid things; like buy a SUV,

or max out a credit card with a 23% interest rate, or work at a job that they

fundamentally dislike, ignore global warming, or vote for candidates that will

take their jobs away from them, or spend wads of cash on hair growth treatments.

Hegemony is the voice in the metaphorical crazy person's head; it is the internalized

agent of social dominance.

Hegemony: noun, leadership or dominance, esp. by one country or social group

over others: Germany was united under Prussian hegemony after 1871.

In the following paper I will describe an historical event, "The Great Steel Strike of 1919", and I will delineate the forces that were arrayed against the success of that strike, forces that, at that time, became consolidated in a new form and strategy (which has continued to be developed and refined), regarding the use of propaganda in a vast and compelling way to undermine labor rights and the rights of United States citizens to govern themselves and their country. 1

I will also explore the implications of the development of propaganda on democracy

and the question of scale: propaganda is usually related to a specific situation,

time, or event, but what happens when propaganda becomes the dominant form

of information distribution within a democratic society over a long period

of time?

The propaganda techniques that were initially developed at the beginning of

the 20th century by the large industrial combines have been adapted throughout

our capitalist consumer society, and has now become so pervasive that, I will

argue, it constitutes a willful, and dangerous, reconstruction of hegemony.

For this reason I would first like to provide an overview of hegemony and its

relationship to ourselves as individuals.

When the workers went on strike in 1919 they lived within communities that

believed that the striking workers deserved better pay and conditions. the

public at large supported the strike. Yet a comprehensive propaganda campaign

was able to turn these communities against the strikers, against their own

neighbors, and it was done with deceit and fear mongering.

This demonstrates a power over hearts and minds that has profound implications

and raises fundamental questions: Who are we? Where do our opinions come from?

Why do we hate one group and feel sympathy for another? Why do we go to war

against one country and deify another? Are we, as individuals, making these

decisions or are we simply being obedient to hegemonic influences? These questions

are more relevant now then they have ever been. We are surrounded with media

constantly, and the media itself has been gradually consolidated into the ownership

of larger and fewer corporations. Vast amounts of money are spent to influence

us to buy, vote, and generally behave, in a manner that supports these corporations

(and their parent corporations as well as their subsidiaries).

Successful hegemony is ubiquitous and profound. It must demonstrate it's "natural" power

(dominance) by inhabiting, or co-opting, public and private space. Money and

billboards, corporate logos on clothing and cars, commercials on television,

are all expressions, not only of the desire of a particular company to sell

its wares, but also, and perhaps more importantly, it is a demonstration of

the ownership or control of these venues. In fact advertising and all performance

takes place simultaneously on these two levels; the overt desire to push a

particular product, agenda, or vision, and the demonstration of power over

a particular venue. It is rather like playing piano in a small club or in Carnegie

Hall. If you are performing in Carnegie Hall then you are either an excellent

piano player, are very wealthy (you rented the venue), or you are very well

connected. One other possibility is that you are the janitor, it's 5 am, and

the hall is empty, this option does not really fit in to the hegemonic process.

Hegemony is everywhere, it exists where you are and it exists where you are

going. It is larger then you and it is larger then the span and distance of

your life, or at least that is the impression hegemony would like to convey.

But ubiquity is not enough. Weeds are ubiquitous, yet they do not dominate

our lives (unless we have a garden). Hegemony also must dominate the mythos

of a culture. It must co-opt existing mythologies and generate new mythologies.

Christmas was a pagan event (the Winter Solstice) co-opted by Christians into

the birthday of their messiah; Jesus Christ. This was an expression of Christian

hegemony, which has further evolved into an expression of the capitalist consumer

hegemony resulting in the orgy of credit spending called "The Christmas

Holiday". The populace spends a great deal more time in the mall then

in a church, and the major portion of their "tithe" is given to Toys-R-Us.

This is why I used the word "profound". The mythos of a culture is

the internalized symbology that is carried individually within all of us. It

is both a very intimate and personal part of ourselves, and a connection with

a larger social group. Culture exists as an aggregate of the beliefs and expression

of a mass of individuals, people creating their unique version of the prevailing

culture. By manipulating our personal and social symbology we are kept allied

with the dominant power structure.

So, while culture may appear to pour forth from some giant media machine, in

truth it is something that is being continually created by everyone within

the group. That is why hegemony must be both ubiquitous and profound; to be

effective it must reach each person individually on a personal and intimate

level. The media machine is essentially shaping, managing, and profiting from,

the cultural impulses and inclinations of millions of individuals.

In the Roman Empire the emperors exerted hegemony by having statues of themselves,

in particular garb and pose, built all over the place as well as having their

visage placed on the empire's coinage. Liberal or conservative could be expressed

by the formal (liberal) or military (conservative) garb worn by the statues.

Also a hand on a sword hilt or a pair of marching sandals could convey messages

regarding the intentions and management style of the emperor. All of this backed

up by the Roman Legions and their very real, and readily accessible, swords.2

In other words hegemony is not new and is an integral part of governance and

social organization. People instinctually align themselves within the pecking

order of social structure and part of that process is psychologically internalizing

the system, viscerally recognizing power and their relationship to it. We all

do this whether we like it or not, and that's the problem. Hegemony at its

worst places everyone in a box, unable to imagine viable alternatives, unable

to even speak of the possibilities. Second Wave Feminism is an example of the

successful resistance against the oppression of the hegemony of patriarchy.

This process (often referred to at the time as "consciousness raising")

required individual women to challenge their own perception of self as well

as to challenge the men and women in their lives in order to improve their

power relations within their society. In other words: for feminism to succeed

it had to get personal.

Casting coins

and statues are real tasks requiring significant resources. In these times

(the 21st century) the process of hegemony has become incredibly sophisticated.

The technology of mass communication and the advent of large democratic states

have combined to undermine the use of fear and intimidation as a tool of

governance. An authoritarian state does not require propaganda as a tool

to the degree that a democratic states does. A tyrant simply tells the people

what is going to be done, whereas a democratic state must influence the masses

to support their agenda. The "values" of the democracy

must appear to be supported by the actions of the rulers, whether or not those

actions are actually supportive or representative of the majority of the population.

This is a great deal more complicated then simply having military parades and

painting the benign yet severe visage of the leader on every large wall, as

well as sustaining a sizable secret police force. A democracy requires an extensive

propaganda apparatus that does not appear to be a propaganda apparatus.3 The

populace must trust in the information they are receiving from the various

media, including government pronouncements, and private media news sources.

In the United States we have this apparatus and it has primarily developed

over the last one hundred years. Prior to this time big business applied propaganda

as a specific tool for a specific group, it did not exist as a national structure

aimed at the population as a whole. This change occurred as the result of a

number of factors, the two most prominent being the United States entry into

WWI and the rise in immigration at the beginning of the 20th century.

In the early 1900s there was a huge wave of immigrants that arrived from Europe.

Between the years 1900 and 1910 8,024,000 immigrants entered the United States.4

In 1910 14.6% of the US population was foreign born, compared to 8.5% of the

population in 1990.5 Many of these immigrants walked off the dock and straight

into the factories and mines. The vast majority did not speak English nor did

they have any real understanding of the culture and economic structure they

were entering into. And, worse yet, some of them brought political ideas that

were inimical to the owners of the factories and mines.

In 1907 a group of conservative business leaders got together and formed the

North American Civic League for Immigrants (NACLI).6 It was intended to teach

immigrants English and to promote the idea that it was best to trust your bosses,

trust the government, hate communism, and stay away from those troublesome

unions. They called this the Americanization Program.

Its methodology was to investigate the conditions of immigrants and to direct

the attention of charitable organizations to the immigrants needs, in the hope

that this would diminish the influence of radicals within labors ranks. In

other words the NACLI was formed to do two things: resist the union movement

that was gradually gaining ground, and to offset the growing (and accurate)

sense in the general population that capitalist were greedy monsters. In 1910

the League undertook an investigation of the industrial conditions in the New

England textile cities of Lawrence, Lowell, Haverhill, and Manchester, which

were showing increasing labor unrest.7 In particular the success of the International

Workers of the World Union (IWW) to organize in the area created real consternation

among the industrialist. The League encouraged the investment of funds into

the area. This proved prescient yet was unsuccessful.

In 1912 25,000 textile workers went on strike. They immediately invited the

International Workers Union (IWW) to assist in organizing the strike against

the Woolen Trust, represented chiefly by the American Woolen Company in Lawrence,

Mass. The workers had not been unionized and were striking out of sheer desperation:

"The Lawrence workers earned 'destitution' wages. They had for years been forced to live in slums... with as many as 17 people to five rooms. One in six children died before their first birthday. Those who survived had rickets and diseases of malnutrition."8

The strikers decided after the strike had gone on for several weeks to move their children out of Lawrence, for their safety and support. While a group of children and their mothers were waiting at the train station, company mercenaries with fire hoses and clubs attacked them. The company owners were angry at the sympathetic publicity that moving the children had created for the strikers and decided to stop it from taking place. Yet the brutality exhibited by the goons created even more publicity and public sympathy moved strongly to the strikers. Shortly thereafter the owners gave in and the strike was won.9

Five days after the end of the Lawrence strike the NACLI met and decided to

expand their Americanization program by contacting and gaining the cooperation

of Chamber of Commerce and other business organizations across the nation.

The limitation of NACLI was that they were attempting to propagandize the workers

themselves through the Americanization program. Yet they lost the strike due

to public outcry against the industrialists. In other words it was the public

perception of injustice and brutality that won the strike for the workers,

not the numbers of workers who were successfully brainwashed.

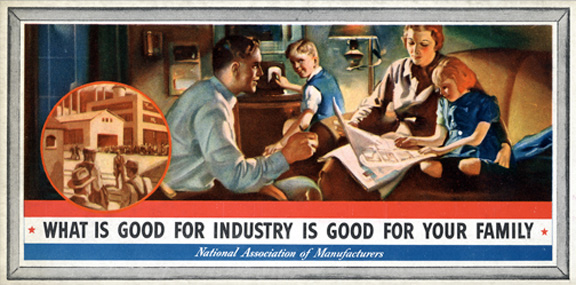

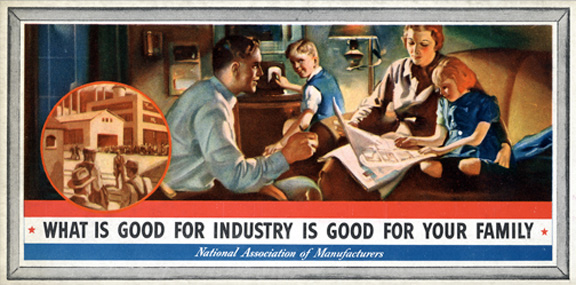

Corporations were already engaging in large-scale propaganda with the intention

of influencing local, state, and national, legislation and the election of

individuals who would favor their agenda. In fact, in 1913 a committee of the

US Congress was formed to investigate the use of propaganda by the National

Association of Manufacturers (NAM). It reported: "That the aspirations

of the NAM were so vast and far-reaching as to excite at once admiration and

fear - admiration for the genius that conceived them and fear for the effects

which the... accomplishments of all these ambitions might have in a government

such as ours. (Lane 1950:58)"10

This report's release coincided with the beginning of WWI. Propaganda campaigns

were gaining in popularity among the powerful.

In 1916 it became clear to Wilson that it would be, he felt, in the interests

of the United States to enter into the war, but the majority of the population

did not agree. To the American people the war seemed like another European

quagmire, a war based on a complex of treaties (some secret) and the greed

of industrialists. There seemed to be few issues of justice or any compelling

advantage to the US. In fact the US was making a good deal of money staying

neutral, importing an increasing amount of goods to England and France due

to the war. Also many Americans were of recent German ancestry, so there was

a good deal of ambivalence regarding whose side to support. The American people

had little desire to enter the fray.

Yet there were business and political interests that strongly supported a military

intervention on the side of the allies. Many of the ruling elite felt that

it was time for the United States to enter onto the world stage, to become

a major international player, economically and politically, and by intervening

on the side of England and France the US would have a major influence on the

postwar reconstruction.11

President Wilson agreed, and during 1917 he created the "Committee on

Public Information" (CPI), which would oversee the first extensive national

propaganda campaign in order to stimulate support for entering the war. This

included the employment of 75,000 "Four-Minute Men", who would give

pro-government and pro-war speeches at any public gathering, including movie

theatres where they would stand and speak while the reels were being changed,

also 75 million pamphlets were printed and distributed, "war expositions" were

sponsored in over two dozen cities (attended by 10 million people), 6000 press

releases were issued to influence newspapers to support the war, and they produced

movies with titles like; "The Prussian Cur" and "The Kaiser:

the Beast of Berlin" (and presumably Four-minute Men were leaping up and

speaking while the reels were being changed).12

They also placed full-page ads in mass magazines exhorting people to report

anyone who spoke against the government or the war. Kennedy describes the effects

of this propaganda:

"The American experience in WWI (as indeed the experience of many other belligerents in that war) darkly adumbrated the themes Orwell was to put at the center of his futuristic fantasy [1984]: overbearing concern for "correct" opinion, for expression, for language itself, and the creation of an enormous propaganda apparatus to nurture the desired state of mind and excoriate all dissenters."13

The campaign was successful, patriotism and loyalty blossomed, bringing with it a "rank nativism"14 and anti-radicalism. With certain inevitability the pro-war campaign of "preparedness" (for war) would combine with the Americanization program.

"To a significant degree, the concern for preparedness and the concern for forced assimilation [of immigrants] flowed from the same anxiety about the flabbiness of American society in a hostile world. It was not surprising that the two campaigns had commingled."15

Government and the Industrialists were cooperating to support our intervention in the war, to eliminate "radical" (pro-labor) influences, and in a militant and nativistic assimilation of immigrants. All of which, in one-way or another, supported the interests of Big Business. This cooperation, and repression, would continue throughout the war.

During the war, labor had made modest gains in wages and working conditions.

After the war the industrialists wanted to reverse those gains. This created

conflict with the workers and a number of huge strikes took place. Typically

at that time the factory owners would lock the workers out of the factories,

bring in the Pinkertons (a private security force) and if necessary, the state

or national militia, and hire scabs, usually brought from another region and

of a different ethnicity (thus undermining solidarity with the strikers). The

strikes were violent and of long duration and usually involved the death of

numbers of people, mostly strikers.

Business leaders in the US had watched with interest Woodrow Wilson's pro-war

propaganda campaign. Its success, both in terms of scale and in shifting public

opinion was impressive. There was also a growing awareness by business leaders

that strikes that were supported by the general population, both the local

community and nationally, tended to win. This sympathy included a growing perception

by the public that large businesses were often greedy and exploitive. This

perception was supported by the wages and conditions that actually existed

at the time, hence it could be considered accurate, and that is an important

point. The public, prior to these national propaganda campaigns, had a greater

perception of the truth; that workers in factories and mines were underpaid

and their living conditions were often deplorable.

It was through these campaigns that a distorted and threatening image of workers,

and in particular immigrant workers, became dominant. These images played to

the interests of the industrialists (to keep labor rights suppressed), and

to the government (to keep progressive, particularly socialist, activists in

check, and the small businessman, represented by his Chamber of Commerce, who

also wanted to keep wages low. It also encouraged a paranoia that supported

racist and anti-immigrant beliefs.

In the 1919 Steel Strike 350,000 workers walked off the mill floor:

"The central issue of the strike was, in the words of Samuel Gompers,

'the right of steel workers to bargain collectively' (Murray 1955:149). At

the outset public opinion favored the strikers, who worked an 84 hour week

under deplorable conditions."16

Five days after the strike began the Steel Corporation launched a campaign of full page advertisements; "which urged the strikers to return to work, denounced their leaders as 'trying to establish the red rule of anarchy and bolshevism' and the strike as 'un-American', and even suggested that the Huns had a hand in fomenting the strike."17 The strike was monitored by a remarkable church group; The Interchurch World Movement, which concluded that the strike was lost by:

"...the strike breaking methods of the Steel companies and their effective mobilization of public opinion against the strikers through the charges of radicalism, bolshevism, and the closed shop. None of which were justified by the facts, and through the 'hostility of the press giving biased and colored news.' Under the influence of the steel companies the press built up false charges to make the public lose sight of the real issues. Historian Robert Murray (1955:152) sums up the consequences: 'When the strike ended in 1920 the men had gained not a single concession... twenty lives had been sacrificed and... $112,000,000... lost in wages. Backed by a favorable public opinion which was based on an exaggerated fear of bolshevism, this corporation proved that not even 350,000 striking workers could prevail against it."18

The Steel Corporation had proven that corporations could defeat strikes by the use of propaganda. From this point on strikes would become less violent, which had been the previous methodology, and depend more and more on influencing the public's opinion of the strike.

The public, having been prepared by Wilson's propaganda campaign to fear bolshevism

(or communism), and the immigrants that brought these radical and atheistic

ideas from central and eastern Europe, were easily frightened by the idea that

the entire country was threatened and teetering on the edge of disaster. The

anti-communist movements of the early twenties and later in the McCarthy era

would prove useful for eliminating the left wing of the labor movement (in

many cases the same people that had fought for and founded the union), all

of this based on the fear that communist were fatally undermining our country.

The truth is the 'reds' never constituted any real threat to the government

of the United States at all, never, ever. The numbers of members of the communist

party couldn't have overthrown the government of Toledo, Ohio. What was actually

taking place was the gradual construction of a vast and sophisticated propaganda

apparatus.

The effect of propaganda on the steel workers of 1919 was direct and disastrous.

It not only lost them the strike but it alienated them from their communities.

Not only did they continue to work an 86-hour week at difficult and dangerous

work, they also had been branded as bolsheviks. The communities that were inundated

with this propaganda were also damaged, in that their own perception of their

community, of their neighbors, had been distorted. Their trust in their own

sense of what was and wasn't dangerous had been lessened. They had transferred

some of their ability to discern and discriminate over to the Steel Corporation.

There are two crimes that the Steel Corporation committed: The first involves

the intentional exploitation and abuse of their workers, and the second involves

the equally intentional distribution of lies and fear mongering. The second

crime acted to cloud the nature of the first crime, and the degree of seriousness

of the first crime determined the degree of seriousness of the second. In other

words the degree of mistreatment that the Steel Corporation had committed upon

its workers requires the same degree of propaganda to hide their mistreatment,

a big crime requires a lot of propaganda.

If they had treated their workers with the respect that they deserved they

would not have needed to engage in propaganda. It is rather like Richard Nixon;

if he hadn't been such a sleazy jerk he would not have had to work so hard,

and break so many laws, to prove he wasn't.

Nevertheless, it is one thing for a large and powerful institution (either

private or governmental) to use propaganda to fulfill its aims; it is another

thing when a whole slew of large and powerful institutions (both private and

governmental) work together to promote propaganda. If they are in sufficient

numbers and power, their propaganda becomes all encompassing, dominant, and

hegemonic.

It has been said that capitalism finds its integrity through competition. The

invisible hand of the market will bless or curse a particular enterprise depending

on its ability to create profits for the owners and investors. Competition

keeps the system healthy, killing off the sick and obsolete and leaving the

healthy and adaptable to expand and prosper. This brings to mind the image

of Roman gladiators fighting to the death with the strongest and most effective

warrior surviving. It is a compelling and even seductive concept; a system

that continually rewards the best; the most innovative, the most successful,

and weeds out the ineffective and the weak.

This is a myth. A myth promulgated within our hegemonic system.

The truth is that capitalism encourages the consolidation of capital, since

capital consolidation (profit) is success, and the consolidation of capital

encourages capitalist enterprises to become larger and more diversified in

order to secure the ability to make ever-greater profits. The larger an enterprise

becomes the more necessary it becomes to acquire political power, to accommodate

the ever-larger economic and social footprint of the expanding enterprise.

In this dynamic political power takes on the characteristics of capital, it

becomes something that must be acquired (to be competitive) and in turn must

be sequestered and sustained, it must also be consolidated.

But there are no banks within which you can deposit political power. Political

power, in a democracy, is held within the hearts and minds of the citizenry.

Which greatly disturbs large capital enterprises. It directly threatens their

power to insure a continued growth of profit to their owners and investors

if the political power required to dig more mines, build more factories, compete

with foreign enterprises, eliminate factory and mine waste, insure a supply

of cheap labor, etc. etc. is held hostage to the whims of the general populace.

This problem of how to sequester political power within a democracy was solved

by the construction of a huge propaganda apparatus that would essentially co-opt,

through brainwashing, the political power of the individual, and this apparatus

had to reach the entire population in order to guarantee the necessary majority

of believers, since their will always be some who resist the brainwashing.

The construction of this apparatus reveals another powerful element in this

history: the consolidation of common aims amongst a vast assemblage of corporate

entities, the ability on the part of the Steel Corporation in 1919 to recognize

the need to form cartels with "competitors" and other manufacturers,

specifically designed to sustain and acquire political power. One of the most

glaring examples of this process is the creation of the "National Association

of Manufacturers" (NAM). At its founding in 1895 it had as its agenda:

- The construction of a canal in Central America.

- The retention and supply of home markets with US products and the extension

of

foreign trade.

- Development of reciprocal trade agreements between the US and foreign governments.

- Rehabilitation of the US Merchant Marine.

- Construction of a canal in Central America.

- Improvement and extension of US waterways.19

These were the common interests of US manufacturers in 1895. In 1912 NAM acted as the liaison between the textile interests and the government regarding the Lawrence Strike.20 At this point they opened a "labor department" that would study the issue of the "open shop", in other words, how to resist the unions. Since then NAM has produced, with mounds of spin and deceit, endless "think tank" documents and advertising to support the corporate agenda. Truth is not required. And when it comes to political power corporations do not compete, they cooperate.

In summary: Within the last 100 years a propaganda apparatus has been developed on such a scale as to be considered hegemonic. This apparatus has no respect for the truth; it only cares for what will be most effective to sustain corporate power. The use of propaganda on this scale is damaging both to the individual and to our democracy. The consolidation of propaganda parallels the consolidation of capital (as a necessary congruency), and will continue to strive to expand its control as corporations become larger and gain an ever increasing "footprint" in our society and lives.

And last, but definitely not least, that we as individuals must reflect upon

the source of our beliefs, assumptions, and opinions. If they were acquired

through hegemony, through "groupthink", then we should reevaluate

those beliefs and search for better and more credible sources of information.

It is more important then ever to not be brainwashed drones but to be informed

and educated citizens.

1 Alex Carey, Taking the Risk Out of Democracy, (University of Illinois Press,

Chicago, 1997) This excellent book provided my basic thesis for this paper:

That corporate propaganda endangers democracy, as well as some of the historical

material. Everyone who can read should read it.

2 This information was acquired by listening to a lecture by the Historian

Michael Parenti.

3 Alex Carey, Taking the Risk Out of Democracy, (University of Illinois Press,

Chicago, 1997), 21.

4 Susan Cotts Watkins, introduction to After Ellis Island, (Russell Sage Foundation,

New York, 1994), 1.

5 ibid

6 David M. Kennedy, Over Here, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1980), 64.

7 Alex Carey, Taking the Risk Out of Democracy, (University of Illinois, Chicago,

1997), 41.

8 Ibid, 42.

9 Ibid, 43.

10 Ibid, 21.

11 David M. Kennedy, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1980) 49-53.

12 Ibid, 61.

13 Ibid, 62.

14 Ibid, 67.

15 Ibid, 66.

16 Alex Carey, Taking the Risk Out of Democracy, (University of Illinois Press,

Chicago, 1997), 22.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Information obtained from the National Association of Manufacturers website.

20 Alex Carey, Taking the Risk Out of Democracy, (University of Illinois Press,

Chicago, 1997), 26.