River

Osborn

Well, I’ll Be Dammed

Phillip Hyde, renowned landscape photographer, describes so well what many have

felt during the drawn out battle over the damming of desert canyons. While on

a trip through Glen Canyon shortly before being closed off to the public for

construction, he proclaims:

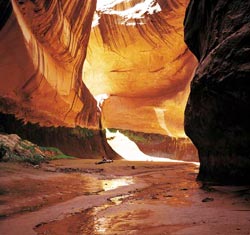

“I needed more time to digest what I saw in the arid lands…In my

memory of the river trip, nights on rocks radiating too much heat for sleeping

are mingled with days of growing awe of the strange forms of this stone country.

My awareness of water as a miracle was born in the shining trickles in the canyon

bottoms and the sudden springs that gushed out of rock as though piped through

the waterbearing Navajo sandstone. These imprints went deep. This landscape

took hold of me.”

This is the story of the confrontation and battle between the people in favor

of building dams and the conservationists. People who were committed to transforming

the West in the name of progress and development for humankind, so that it could

be something more than a “wasteland”. “The West’s water

wizards--politicians, farmers, cash-register entrepreneurs--saw the construction

of the dams as symbols of pride and prosperity”, says Russell Martin in

A Story That Stands Like A Dam. On the other side were the people who were equally

committed to the idea that this space, which was wild and undisturbed, was a

resource to the soul that must not be destroyed. They contended that the dams

and the power they would produce were not needed being that they were being

built in such isolated places. Places so unique to the planet they should not

be bothered. This is the story of compromise and loss for Echo Park Canyon and

Glen Canyon.

The controversy began just after World War II, with the nation teeming with

returning veterans. To get these veterans back into the workforce, part of President

Truman’s “Fair Deal” involved federally sponsored development

projects. One of these was the Colorado River Storage Project (CRSP), (Sproul).

The CRSP was passed by The House of Representatives, with the total estimated

cost at $756 million, one of the largest reclamation projects ever proposed

(Bradley). This was a multipurpose plan undertaken by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

in 1956 to control the flow of the upper Colorado and its tributaries and to

aid in the development of the upper Colorado River Basin, which includes Wyoming,

Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico (Farmer 7). The CRSP stemmed from the

Colorado River Compact of 1922, which states in its first article:

“The major purposes of this compact are to provide for the equitable division

and apportionment of the use of the waters of the Colorado River System…and

to secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial development of the Colorado

River Basin, the storage of its waters, and the protection of life and property

from floods”

This was a time when long-term effects were not largely thought out. No one

argued that the ecology of the region would forever be changed with the building

of the dams; in fact there was not an Environmental Impact Assessment, because

they didn’t exist yet. Development was the key motivation (National Research

Council).

The Federal Government had big plans for the Colorado River and the appropriations

of its waters long before the dams of Glen Canyon and Echo Park Canyon were

even a twinkle in the eye of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamations staff. Both canyons

had been potential dam sites since 1916.

The CRSP was aimed at not only developing natural resources but also at securing

water rights for the Upper Basin states. The Bureau of Reclamation, whose motto

was “Our Rivers: Total Use for Greater Wealth”, proposed that it

and the Upper Basin states construct a series of nine dams, two of which included

sites at Glen Canyon and Echo Park Canyon (Sproul). The dams were to play a

crucial role by regulating the flows of the river, holding during floods, and

releasing during floods, thus constantly delivering water to high-country farms,

ranches, and even to Salt Lake City (Farmer 134).

However, the dam planned in Echo Park Canyon just happened to be located in

Dinosaur National Monument. Despite what one may think, environmentalists didn’t

seem to attack the proposal right away.

In 1949 the Sierra Club was a very regional organization, compared to the national

lobby it has since become. As Martin describes, Sierra Club members at that

time were “a confederation of conservative businesspeople and academics”.

All in all they were not that radical or interested in a conservation cause

that did not involve either the Sierras or general wilderness. In fact, former

club president, Walter Huber, had visited the proposed dam site at Echo Park,

and said that the place was nothing more than “rocks and sagebrush”.

Club director Bestor Robinson argued that the responsible position for the club

to take would be to support the dam. The club’s official response to the

proposals for the dams was to ignore them altogether (Martin 51).

Two years would come to pass before someone else took an interest in the situation.

Sierra Club member Edward Mallinckrodt had been disappointed and confused as

to why the club hadn’t originally taken action and spoken out against

the dam. Whether the land was just “rocks and sagebrush” or not,

the dam site was within the boundaries of a National monument and thus should

be protected. Mallinckrodt brought his concerns to the new executive director

David Brower, who had also had similar feelings (Martin 58).

They believed that the integrity of the National Park Service must be upheld,

keeping commercial and civil resource development out. Their job was to maintain

the pristine wilderness already protected. They backed their argument with the

1916 National Park System Organic Act, which had a specific mandate. In its

“statement of purpose” the Act declared that the purpose of a national

park was to “conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects…and

to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as

will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” (Sproul

4)

David Brower, along with Olaus J. Murie and Howard Zahniser of the Wilderness

Society, launched a public relations assault on federal and state leaders using

letter writing campaigns (and thousands of letters did they instigate), publishing

books on Dinosaur National Monument, and organizing direct pressure whenever

it was possible. Brower began taking key people, such as politicians, from the

communities down the river and through the canyon so that they could see for

themselves the beauty that would be forever destroyed, in hopes that they, too,

would push for the protection of the park (Martin 52). This proved to be a good

tactic.

For the next four years, the environmentalists waged an all-out war against

everyone who was in support of building the Echo Park Dam. In truth, the dam

was popular among residents of both Utah and Colorado, which made the Sierra

Club and Wilderness Society draw needed help from all of their members nationwide.

During the struggle over Echo Park, conservationists created the philosophy

that concern did not solely depend on one’s personal geographic location

but on the principles behind the very idea of protection (Sproul). It was at

this time that the Sierra Club lived up to its self-proclaimed slogan of being

a “Guardian to the West’s National Parks” (Martin 50).

Echo

Park, Dinosaur National Monument

Brower

and Zahniser had never testified before Congressional committees, but they put

the challenge before themselves. They argued not so much against the building

of dams in the Upper Colorado Basin, or the Colorado River Storage Project itself.

They argued that it was not wise water use, or legal, to be building in Dinosaur

National Monument. Brower also disproved some of the Bureau’s engineers’

evaporative statistics. Using his own “simple, ninth-grade variety”

math he showed them that they had forgotten to add and subtract some vital information

surrounding the evaporation concerns. This turned out to be an embarrassment

to the Bureau. Up until that point they had considered themselves heroes. They

had constructed great dams that added to the progress of the nation after the

slump of the depression, and now their authority and professionalism was being

challenged. (Martin 58-59).

Brower

and his colleagues argued that the dam should be built somewhere else for maximum

efficiency. Brower even went on not only to support the building of the Glen

Canyon Dam, but argued that its height could even be raised. It could hold more

water and compensate for water evaporation. Up until that point, Brower had

never visited Glen Canyon, and had a life changing experience on the waters

of the Green River, and couldn’t imagine that any place could be more

beautiful and wondrous than Dinosaur. This was his personal motivation behind

the battle.

After more than half a decade of fighting, debates, hearings, and compromise,

the environmentalists planned an attack from a different angle. They paid for

a full-page ad in the Denver Post, an “open letter” stating that

if Echo Park was not irrevocably eliminated from the CRSP plan, they would launch

an all-out attack against the whole upper-basin project. Congress, not wanting

to call their bluff, finally conceded and agreed to dismiss Echo Park as a dam

site, instead making Glen Canyon the focus of the CRSP (Martin 72). Environmentalists

whooped their victory cry, but not for very long.

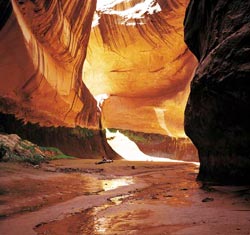

Cathedral in the Desert, Glen Canyon

Up

until this point, Glen Canyon, which was at the time on the Navajo Indian Reservation,

was a fairly unknown refuge for silence and exploration. Other than Reclamation

survey crews and a few boatmen escorting paying customers, the canyon was pretty

much untouched.

Without much consideration, the Government enacted a land exchange with the

Navajos so the dam could be built at the chosen site. The leaders of the Navajo

nation were more than happy to comply at the time, concerned more with the immediate

economic benefits than long-term effects of the dam. Martin reports, “Tribal

leaders sent a telegram to Washington, D.C., explaining that the tribe had completed

a preliminary survey of its lands surrounding the dam site and “LOCATED

IDEAL TOWN SITE ON COOL SOILED MESA SOUTH OF DAM.” And the message assured

the men in Washington that the “TRIBE WILL COOPERATE TO MAXIMUM WITH PLANS

TO LOCATE TOWN SOUTH OF RIVER.” This was because the dam promised the

tribe a significant opportunity. Long plagued with unemployment, lack of power,

resources, and economic income, the tribe found the chance they had been waiting

for--for a long time. Glasser says,

“Congress approved the Navajo Indian Irrigation Project (NIIP) as part

of CRSP in 1962, but never realized that the original plans called for a power

plant at Navajo Dam to pump water onto NIIP’s farmlands. However, the

following year, the tribe entered into a contract with the Utah Construction

Company, one part of the “Big Six” Companies that had built Hoover

Dam, to set aside a 24,000 acre area for strip-mining coal at fifteen cents

a ton. Utah received sale profits, while the tribe received royalties. This

important arrangement would bring power closer to Navajos, provide Navajo labor,

training, and housing improvements, and possible funding for the reservation’s

own coal power generating plant in the future.”

Though very few people had seen the canyon, Brower and the Council of Conservationists

had a general understanding that the heightened dam size, which they originally

encouraged, was going to be so great that the backed up waters might encroach

on the boundaries of Rainbow Bridge National Monument, home to Rainbow Bridge,

the world’s largest natural bridge and home to sacred rituals of the Navajos.

Early on, Secretary of the Interior, Douglas McKay, wrote to Brower to assure

him that the Bureau of Reclamation and the National

Park Service would take all necessary precautions to make sure Rainbow Bridge

was protected. After all the fuss that had occurred with Echo Park Canyon, officials

wanted to avoid triggering the conservationists at all costs.

During 1955 there was an ongoing discussion on what should be done regarding

Rainbow Bridge. Leslie P. Arnberger and Harold A. Marsh, both employees for

the National Park Service wrote to the General Superintendent for Southwestern

National Monuments, suggesting that the Bureau either move the location of the

dam downstream, or lower the level of the dam to the point where Rainbow Bridge

would no longer be at risk. The Bureau of Reclamation was not willing to budge

on the location of the dam; luckily the Park Service was dedicated to protecting

Rainbow Bridge (Sproul 4).

Bureau of Reclamation assured there would be funds available in the dam’s

budget for protective measures. These would include a barrier dam below the

bridge, a diversion tunnel above the bridge, and a catch basin at the tunnel

outlet. (Sproul 5)

Despite the fact that Rainbow Bridge would be safe, from harm’s way, some

of the key conservationists began to wonder why they didn’t fight the

whole of the CRSP. Even after the victory at Echo Park Canyon, Brower had wanted

to keep up the opposition to the dams. The Bureau of Reclamation’s uncertainty

about the dam’s specifications and the cost of the whole project seemed

like enough ammunition to use against them. However, the Sierra Club board reminded

him that their fight had been the one over Echo Park Canyon, and since they

had won, the fight was finished (Martin 72).

***********

Ken Sleight, who had a small business taking kids, Mormon youth groups, down

the river in Glen Canyon, had differing ideas about the dam. He was familiar

with Echo Park Canyon yet couldn’t understand who in their right mind

would ever trade it for Glen Canyon. Sleight was not only a desert rat river

guide, but was also the president of the Escalante Chamber of Commerce, and

had helped his friends form the Western River Guides Association (WRGA). The

WRGA was working to protect their commercial interests, and didn’t understand

why the conservationists didn’t just attack the CSRP as a whole (Martin

171).

Sleight, some of his river buddies, and some of the outdoor activists from the

University of Utah decided to form Friends of Glen Canyon. Their name proclaimed

their mission, yet they didn’t have a clue of how to tackle it. The conservation

groups who would have been their allies had pushed for the dam, and it seemed

everyone accepted that the canyon would be flooded—politicians, chambers

of commerce, civic and church groups, and wildlife organizations (Martin 171).

With all the support for the dam, the challenge seemed daunting.

Friends of Glen Canyon worked out of Salt Lake City, searching for funds and

trying to make headway with the politicians. They tried their best to remind

everyone they could that just over a decade earlier, FDR was on the verge of

making the Glen Canyon country the largest national monument in the nation (Martin

172). How had people forgotten that so quickly?

They also tried to make a case regarding the overwhelmingly abundant history

of the area. From the Anasazi to the Hole-in-the-Rock pioneers, to Powell’s

expeditions and the gold-crazed miner—this place had major history. To

address water issues, they argued that it may be more beneficial to have many

smaller water-storage facilities located in the upper valleys where people actually

resided instead of a huge dam way out in the middle of nowhere (Martin 172).

Brower, who had a change of mind in 1955, also began to fight in the name of

Glen Canyon, to the dismay of the Sierra Club. It wasn’t so much the beauty

he was worried about, he still hadn’t paid the canyon a visit, but it

was the unreliable evaporation data from the Bureau of Reclamation and the cost

of building the dam. However, with the Sierra Club victory with Echo Park Canyon,

Brower would now have to fight alone (Farmer 144). This time he was not up to

the challenge, and later on said that not fighting against the Glen Canyon dam

was his biggest regret in life.

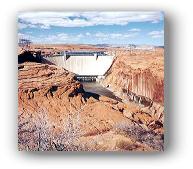

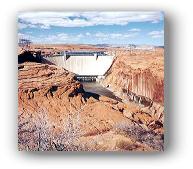

In the end, their cries of injustice were not heard, and the Glen Canyon got

its death sentence. On October 15,1956 the echoing sounds of the first blast

were heard and felt in the souls of all those who fought for and against the

dam. The dam continues to be a hot topic to this day, people fighting for and

against its decommission.

“It is so dim…so eerie…so quiet and humanless…so cool…that

only a photograph could explain it…we feel creation all around us, deep

in the womb of Mother Earth. We touch her scars and now and then, with the wonder

of it, there are tears in our eyes. We feel we have been let in on a great secret-and

we have! When I think ahead, I begin to choke…this will all be under water”,

writes Katie Lee on October 10, 1956 while exploring Dungeon Canyon, just four

days before the blasting of the Glen Canyon Dam in northern Arizona began.

The dam took ten years of construction and over seventeen years to completely

fill creating “Lake” Powell.

The Bureau of Reclamation finally won the chance to build “the big one”.

Due to the passion it drew from many people near and far, who had and hadn’t

seen this raw natural beauty, the Bureau may never have a chance to construct

such projects without the battle of a lifetime.

Many environmentalists took this story to be a good lesson and warning for future

compromises: do not trade something away of which you do not already know.

Glen Canyon Dam, Page Arizona

“Oh Desert, yours is the only death I cannot bear.”

-Edward Abbey