Deserting the Deserters

By Sandy Robertson

"There was a more serious problem. He lay in his bunk pondering upon

it. He tried to mathematically prove to himself that he would not run from

battle."1

In times of war, there occur a number of situations that are intolerable to

some soldiers, who resolve their situation by deserting their posts. We know

that deserters were part of World War I; unfortunately, government and society

have opted to minimize their existence as a part of the process of war and

military service. The military history of the United States is incomplete because

there is little documentation about those who deserted. By ignoring and eliminating

the discussion on desertion, we are essentially changing military history and

the history of our country. We are suppressing their story and their contributions;

we are deserting the deserters.

1917 was the first year of draft registration under the Selective Service Act. Uncle Sam took the youngest soldiers first, likely because of their high level of energy and excitement, but perhaps because they were viewed as the most expendable age group (not yet fully mature and less likely to be married with families of their own). Reasons and rationale for much of the government actions in wartime are purposefully difficult to find. With that in mind, an exploration and discovery on the occurrence of desertion in World War I is both complicated and challenging; some assumptions must be made due to the lack of information available.

The best way to tell the story is to create a hypothetical journey for a fictional

veteran of World War I...

Registration and Induction

Jimmy Daniels grew up in Olympia, with his parents and five siblings. Jimmy's

father worked in the lumber mill just down the road from their small house.

Jimmy's mother provided laundry and sewing services to some of the wealthy

families in the area. To help his family financially, Jimmy left school in

the ninth grade to work in the lumber mill with his father.

On May 18, 1917, the Selective Service Law established a draft for the Great

War. At age 21, Jimmy was sure his name would be called to register and he

was incredibly excited about it. He wanted to fight for his country and make

his family proud. He waited impatiently for the call to service. And so, when

he was contacted by the Local Board of Exemptions for Thurston County, Jimmy

was ecstatic! He hurried to the downtown office in the winter of 1918 and completed

the paperwork. Jimmy was classified as a 1A, which meant he was "available

for unrestricted military service."2 The local draft board directed him

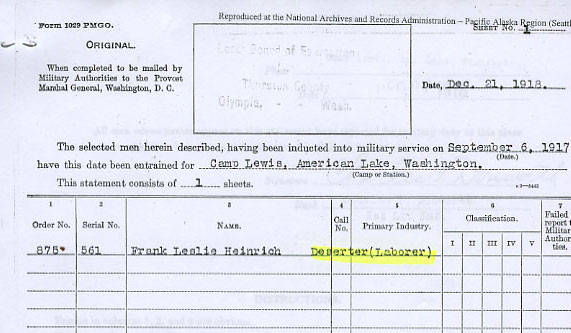

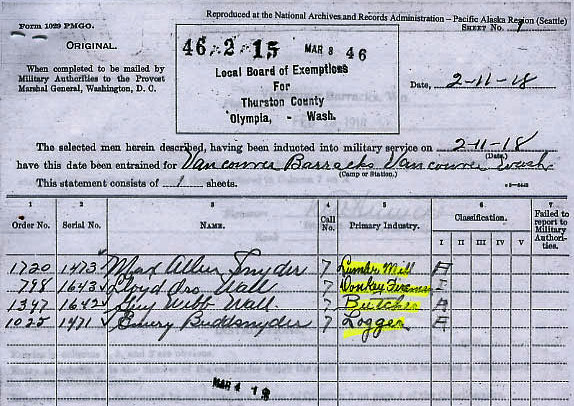

to prepare for departure. The induction Form 1029 listed several local residents

who were accepted for service; they were to report for military duty at the

Vancouver Barracks on February 19, 1918.

Private Daniels Reports for Duty

With a new title, Private Daniels learned how to be a soldier - he thought

his aim wasn't half bad, but the Sergeant said he needed to work on his speed

and accuracy. Private Daniels traveled overseas and was sent to the front

lines of the war. He wasn't feeling quite so sure of himself anymore, but

knew in his heart that he was doing the right thing. He followed the directions

he was given and killed several German troops on his first day at the front

line.

That evening, Private Daniels' losses weighed heavy on him. Two comrades were

killed in the day's battle. He had found the killing of another person to be

a most difficult task that shook the foundations of his soul. But the most

difficult event of that day was seeing a fellow soldier, Hank Jacobs, leave

the battlefield, deserting his friends and his country at a critical time.

Private Daniels thought about the reasons Hank might have deserted. He at first

thought Hank to be a coward, but juxtaposed against his feelings of grief for

his own actions that day...perhaps in deserting, Hank had actually done something

rather noble. His absence likely resulted in a number of people (albeit, the

enemy) being saved from death; on the contrary, perhaps Hank's absence from

the front line was the root cause of the death of fellow soldiers. Private

Daniels was exhausted trying to sort out the morality of desertion; it was

just too complicated an issue.

One week later, Hank arrived back in camp. He wasn't readily welcomed by his

former friends and fellow troops; rather, he was looked at with disgust and

loathing. Private Daniels learned that this was the first time Hank had ever

been away from the small town where he grew up and he was incredibly homesick.

Hank panicked at the gunfire and chaos that he saw on the front line. As Hank's

story became known, the other soldiers slowly and reluctantly welcomed him

back, although they didn't know if they could count on him in battle. If the

truth were known, the other soldiers were just as afraid as Hank had been.

Thus ends the fictional experience of Private Jimmy Daniels.

Functionality of Records

The story of Private Daniels provides a glimpse into the processes of registration

and induction, as well as a potential military view of desertion. A closer

look is needed to fully understand the registration and induction process,

which appear to have been unorganized and inconsistent.

The registration process was a huge undertaking by the U.S. Government and

began with the establishment of a system of draft boards. District draft boards

had jurisdiction over a multitude of smaller, local boards. Each local board

was tasked with the registration and classification of draftees; additionally,

local boards kept track of the status of each registrant via induction forms,

which recorded the name and primary industry of each draftee. A very narrow

sampling of induction forms from the Local Board of Exemptions in Olympia,

Washington, revealed a variety of names and industries, and also identified

two different stations for inductees - Camp Lewis, American Lake and the Vancouver

Barracks, Vancouver.3

As Jeanette Keith so easily explains it, "the historical record does not tell us much about John Smith, just that he was a deserter, a husband, a father, and a son and that his family desperately wanted him to stay home."4 Nevertheless, the historical record does shed additional light on who the deserters might have been -- a researcher might discern from the historical requests for deferments what the special needs and circumstances were that weighed heavily on those deserters who had been denied deferment.

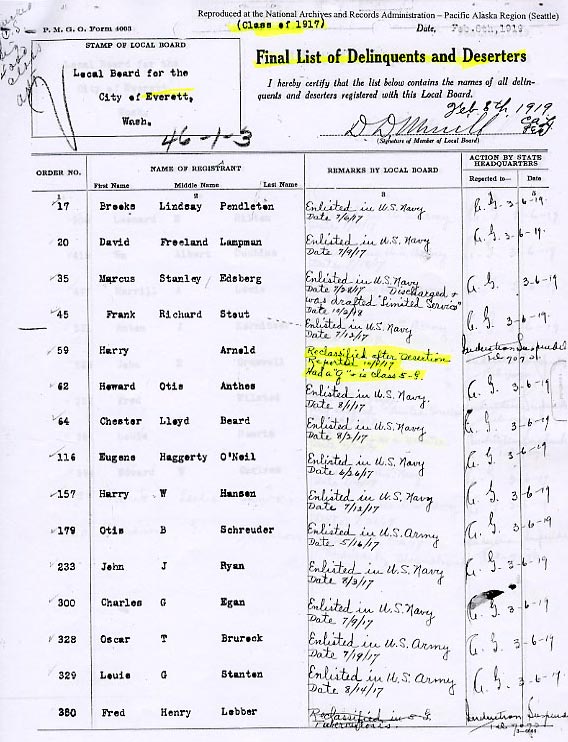

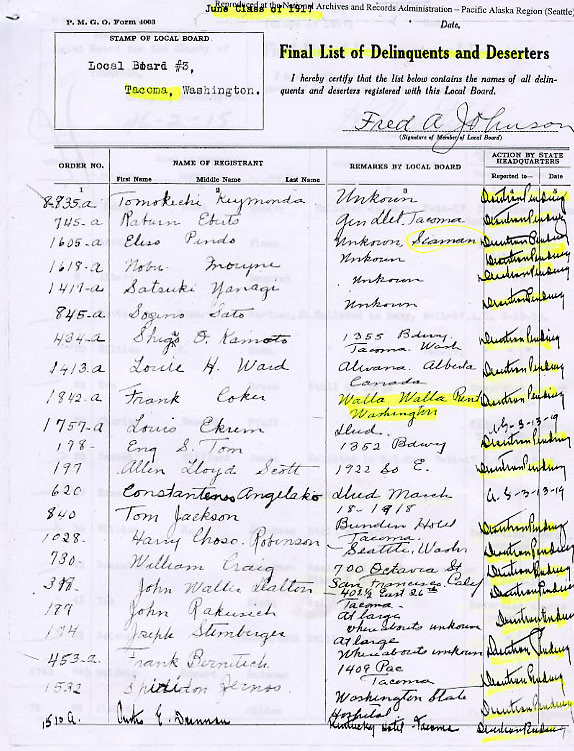

At the end of World War I, it appears that each district board was tasked with "balancing

the books," in terms of accounting for the registrants and inductees from

their assigned geographic area. Government Form 4003, Final List of Delinquents

and Deserterswas apparently one of the tools by which local boards tracked

this information. The use of this form does not seem consistent, either by

a specific board or by a specific district. The section on the form titled "Remarks

by Local Board" sometimes reflects the name of a country, or it may indicate

the person has enlisted in a specific branch of the military, or it may indicate

a reclassification. Following are two examples of the disparate use of Form

4003 in Everett and Tacoma Washington.

Example #1: A sample listing from The Class of 1917, Local Board for the City

of Everett, February 8, 1919, shows 85 registrants, with 32 of those noted

as having desertion charges pending. The local board remarks for this sampling

include:

Reclassified after desertion reported

Sent to camp as a deserter

Norway

Sweden

Sent to camp as a "wilful" deserter

Sent to camp as a "non-wilful" deserter

Discharged by camp commander as a "wilful" deserter"

Page one of this sampling shows that most draftees had enlisted in the U.S.

Navy or Army and one was reclassified after desertion:5

Example #2: A sample listing from The Class of 1917, Local Board #3 for Tacoma,

shows 22 registrants, with all but two having pending desertion charges against

them; although the writing is difficult to read, it appears these two have

board remarks indicating their dates of death. It should be noted that many

of these specific registrants appear to be of foreign descent. 6

Newspapers served as a multipurpose tool for the military. The names of deserters were often published in local newspapers with the intent of garnering assistance in locating deserters; however, this practice was also a deterrent to soldiers, who did not want the embarrassment of being on a public list of deserters. An article in The New York Times in May 1921 points to the inaccuracies of some of the published lists of deserters in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Reportedly the lists had been reviewed and approved by the local draft board; however, the lists still included the names of war veterans who had served honorably. One such list included the name of a man who had been killed in October 1917 by "boy bandits"; another list included the names of soldiers killed in combat. The Pennsylvania Draft Director was outraged at these injustices against war veterans whose reputations should not be tarnished by such incorrect information.7

Records and forms were obviously not kept or used in the same manner, nor with

a high degree of accuracy. With the apparent dysfunctional record-keeping on

the home front, it would seem that a significant amount of time would pass

between the declaration that a soldier had deserted and the receipt of that

information in the United States by the local district board. Without knowing

how much time that relay of information would take, perhaps the deserter would

be caught and re-assigned or sent to re-training before the local board even

knew the person had deserted.

A Deserter Is...

Jeanette Keith offers a variety of potential reasons for desertion in World

War I: religious beliefs that did not agree with war; conscientious objection

to the war; family obligations (children/wife or elderly parents); anger

over the social injustice of deferments being given to the wealthy, but not

the poor; political opposition to the war; and poor treatment of soldiers.

Keith provides the example of Robert Marks of Mississippi, who worked the

Selective Service System to his advantage:

Also a married man, Marks had first tried to get out of the army by claiming

dependency; that failing, he had filed an agricultural deferment; that failing,

he had showed up for his induction at Camp Pike, in Little Rock, with medical

affidavits claiming that he was too ill to serve. Complaints that Marks had

bought his way out prompted a Bureau of Investigation inquiry, but the provost

marshall general's office decided, in February 1918, to let the matter go:

Marks would be reclassified anyway when he filled out the Selective Service

System's elaborate new questionnaire.8

Keith states that of the 95,308 southern deserters in 1918, the majority were

black men.9 With great concern over this information, the Provost Marshal General

contacted southern governors and asked for their thoughts regarding the high

number of black deserters; one responded that the black deserters were ignorant

and migratory. Authorities latched onto the idea of ignorance, thinking that

by explaining desertion as being a misunderstanding, the soldiers (and government)

would save their reputations. To lure some of the deserters back, one county

in Arkansas held "what amount to a deserters' fair", encouraging

their return for immediate re-training; 110 deserters showed up and most were

sent to camp.10 It should be noted that the issue of race has been carefully

studied by Campbell C. Johnson, who reported two reasons for the high rate

of desertion among Negroes -- ignorance and/or illiteracy and their need for

better job opportunities that were available in the industries of the North.11

One group of forty deserters was ready to fight efforts to be arrested. These

men, hiding in Ashe County, North Carolina, caused the government much frustration.

The Adjutant General was sent to assess the situation; he subsequently requested

the Governor provide an organized force. The sheriff of Ashe County supported

the deserters and so would not help the government officials in any way. And

so, Governor Bickett traveled to Jefferson to address the citizens; he believed

they deserted because they didn't know the truth about the war, which he proclaimed

to share:

If in the face of this defiant and contemptuous challenge our Government had

folded its arms, then today Old Glory would float to the breezes in lonely

isolation as the one flag on this earth that no other nation loves, no other

nation fears, and no other nation respects. We had to go in to preserve a single

vestige of our self-respect and the respect of others.12

Yet another variety of deserter was described in 1918 by The New York Times, "the

monotony of military life in years of peace, its aimlessness and idle hours,

have been considered by competent observers as a chief cause of desertion."13

For those troops who were not on the front lines during war-time, perhaps boredom

might have been a desertion factor.

Punishment -- Execution, Prison, or Re-Training

The 1911 War Department policy for desertion was strict, although leniency

was given under special circumstances, such as youth. "There are now

additional means of saving men to the colors - men whose offenses are thoughtless

acts due to youth or inexperience or committee under some special stress, and

for these reasons have in them less of the element of culpability."14

For those deserters that did not have a youthful defense, there was little

sympathy. Regarding the deserter:

His engagement, supported by an oath of allegiance, is that the Nation may

depend upon him for such service during the fixed period, whatever may be the

emergency. When this engagement is breached a high obligation to the Nation

is disregarded, a solemn oath of allegiance is violated, and the Government

is defrauded in the amount of its outlay incident to inducting the soldier

into the military service, training, clothing, and caring for him while he

remains in that service, and transporting him to the station from which he

deserts. Desertion is thus seen to be, not simply a breach of contract for

personal service, but a grave crime against the Government; in time of war

perhaps the gravest that a soldier can commit, and at such times punishable

with death.15

While many deserters were sentenced to execution, all such sentences had to

be referred to President Wilson for review. According to a 1918 article in

The New York Times, the President always "saw fit to order commutation".16

Imprisonment was typically the alternative, with the routine sentence being

between ten to twenty years' confinement. Long-term confinement of at least

one year was usually at a federal or state penitentiary, while shorter-term

confinement was at disciplinary barracks; at the United States Disciplinary

Barracks at Fort Leavenworth some deserters received intensive practical training

so they could re-enlist for service.17

The Numerical Picture

Annual Reports from the various military service branches and the War Department

provide an interesting lens by which to look at the prevalence of desertion.

| Service Branch | Status of Deserters |

1917 |

1918 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Army 18 | Charged |

2,818 |

3,358 |

Convicted |

1,718 |

1,553 |

|

| Navy 19 | Deserted (details below) | 1,985 | 2,203 |

| --at large | 1,692 | 1,697 | |

| --Convicted | 426 | 516 | |

| --Mark of conviction removed | 33 |

10 |

There seems to be little comparison with the above statistics and Keith's statement

that there were 95,308 southern deserters in 1918. Many reports and sources

indicate that the military reviewed each case of desertion and often changed

the status. It is assumed that, by changing/upgrading the status, the number

of reported desertions was dramatically reduced, which in turn made the problem

of desertion less prevalent. The War Department reported in the 1917 Annual

Report that the number of actual desertions occurring during the year is unknown:

...because it is impossible at this time to even estimate the number of men

now regarded as deserters that will come under military control and be acquitted

of the charge or be convicted of the lesser offense of absence without leave

before the statute of limitations will apply in their cases. Under the law

now in operation the trial of the men who enlisted and deserted during the

fiscal year 1917 will not be barred by the statute of limitations until some

time during the fiscal year 1920. Unless it can be assumed that all men reported

as deserters during the year who do not return to military control or have

not been tried before the annual report for that year is published can be classed

as deserters, the actual number of desertions during the year can not be stated

in the report for that year. As cases have arisen in which men have been convicted

of absence without leave after having been absent more than two years from

the date of their reported desertion, no such assumption is possible.20

Limitations on Disclosure

Prior to World War I, desertion was already a concern. In September 1910,

The Cosmopolitan Magazine published a story titled "The Shame of Our Army" about

a deserter and the deplorable conditions and dishonorable practices within

the U.S. Army. The article was prefaced with a note from the editor addressing

criticism received from petty officers about an article on desertion. The

Cosmopolitan Magazine defended its decision to publish the article:

...in bringing to public attention one of the greatest weaknesses of our

military organization a real benefit was conferred, for if the system is

not the highest efficiency in respect to its treatment of recruits it is

time it was made so...That the present methods of dealing with the deserter

are both stupid and short-sighted is the opinion of many well-informed military

officers of high rank, including the commander-in-chief of the army, President

Taft.21

The Cosmopolitan Magazine's article was then used by The New York Times as

the foundation for a follow-up article in 1911, in which the same deserter

provided the details of his desertion and subsequent prison sentence. It appears

that media coverage of desertion before World War I was not well-received by

the military; whether the government encouraged the petty officers to complain

is unknown, but it is conceivable.

Further limitations are seen within historical government documents, which

contain sparse information. Apparently, the history of war is being shaped

by the disappearance, unwillingness to disclose, or inability to find the documents

that would explain the occurrence of desertion. There are significant documents

available, although they are reportedly in various states and facilities; accessibility

and availability is questionable, as is the ability to complete such research

without extensive travel.

Another source of historical information is the media. A review of newspaper

clippings from the Tacoma News Tribune revealed a noticeable absence of stories

on desertion. Was a conscious decision made by the media to ignore news about

deserters, or was this a demand placed on the media by the government? Another

possible explanation is that the selection of clippings from the Tacoma News

Tribune did not include stories on desertion - a decision made by an archivist,

perhaps.

In Conclusion

Most military draftees completed their service and returned home from World

War I; others were listed as casualties. A number of military registrants

were identified as deserters, having abandoned their military assignment.

There is no known survey or government statistical report that helps us understand

why military personnel chose to desert their post. Speculation is rampant and

perhaps unreliable. Information, records, and history are noticeably absent

much information on military desertion. There are many vague suggestions in

the writings and sources that the government and military leadership purposefully

chose not to release desertion information or discuss the subject, lest a negative

shadow be cast upon the military and the government.

Without the details, this gaping hole in history will remain. We have deserted

the deserters.

Works Cited

Crane, Stephen.

Red Badge of Courage. http://www.redbadgeofcourage.org/text.html>.

10 March 2007

Johnson, Campbell C. "The Mobilization of Negro Manpower for the Armed

Forces." The Journal of Negro Education 12 (1943): 298-306.

Keith, Jeanette. Rich Man's War, Poor Man's Fight: Race, Class, and Power in

the Rural South During the First World War. Chapel Hill: The University of

North Carolina Press, 2004.

United States. A Manual for Courts-Martial: Courts of Inquiry and of Other

Procedure Under Military Law. Washington Government Printing Office. 1918.

United States. War Department: Annual Reports, 1918. Washington Government

Printing Office. 1919.

United States. Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy For the Fiscal Year.

Washington Government Printing Office. 1918.

United States. War Department: Annual Reports, 1917. Washington Government

Printing Office. 1918.

University of North Carolina, "The Ashe County Case: Electronic Edition.

Bickett, Thomas Walter, 1869-1921", <http://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/bickettashe/bickett/html> 28

Jan. 2007. This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at

Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and

personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the text.

"Deserter's Story Stirs Army Officers: Rigid Investigation Ordered of

Abuses in the Service Described in a Magazine Article: Seek to Trace the Author;

Man Who Gave Millard His Information Thought to be Member of a Prominent Family." The

New York Times 2 Jan. 1911.

"Disputes Defense of Slacker Lists: Pennsylvania Draft Director Cites

Instance of Army Declining Checking-Up Aid. More Injustices Shown. Bronx Man

Slain in Brooklyn Oct. 29, 1917, Named as Deserter - Sergeant, Who Enlisted,

Another." The New York Times May 1921.

"Punishing the Army Deserter: So Far America Has Not Inflicted the Death

Penalty - Even Those Who Slept at Posts Have Escaped, but Severer Retribution

is Ahead." The New York Times 16 June 1918.

"Record Group 163." National Archives and Records Administration.

Pacific Alaska Region (Seattle).

"Selective Service." Wikipedia. 2007. 10 March 2007 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selective_Service#Classifications>

"Uncle Sam." Wikipedia. 2007. 10 March 2007 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncle_Sam>

1 Stephen Crane, Red Badge of Courage, <http://www.redbadgeofcourage.org/text.html>, Chapter 1, 10 March 2007.

2 Wikipedia, <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selective_Service#Classifications>,

10 March 2007.

3 "Record Group 163," National Archives and Records Administration,

Pacific Alaska Region (Seattle)

4 Jeanette Keith, Rich Man's War, Poor Man's Fight: Race, Class, and Power

in the Rural South During the First World War (Chapel Hill: The University

of North Carolina Press, 2004) 1

5 National Archives and Records Administration. The local board incorrectly

spelled "wilful"; however, their choice of spelling was consistent

throughout this specific record.

6 National Archives and Record Administration

7 "Disputes Defense of Slacker Lists: Pennsylvania Draft Director Cites

Instance of Army Declining Checking-Up Aid. More Injustices Shown. Bronx Man

Slain in Brooklyn Oct. 29, 1917, Named as Deserter - Sergeant, Who Enlisted,

Another." The New York Times May 1921.

8 Keith 178.

9 Keith 179.

10 Keith 181.

11 Campbell C. Johnson, "The Mobilization of Negro Manpower for the Armed

Forces," The Journal of Negro Education 12.3 (1943): 300.

12 University of North Carolina, "The Ashe County Case: Electronic Edition.

Bickett, Thomas Walter, 1869-1921", <http://docsouth.unc.edu/wwi/bickettashe/bickett/html>.

28 Jan. 2007. This work is the property of the University of North Carolina

at Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching

and personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the

text.

13 "Punishing the Army Deserter: So Far America Has Not Inflicted the

Death Penalty-Even Those Who Slept at Posts Have Escaped, but Severer Retribution

Is Ahead." The New York Times 16 June 1918.

14 A Manual for Courts-Martial: Courts of Inquiry and of Other Procedure Under

Military Law, Washington Government Printing Office (1918) 157.

15 A Manual for Courts-Martial: Courts of Inquiry and of Other Procedure Under

Military Law, 158.

16 "Punishing the Army Deserter: So Far America Has Not Inflicted the

Death Penalty-Even Those Who Slept at Posts Have Escaped, but Severer Retribution

Is Ahead."

17 A Manual for Courts-Martial: Courts of Inquiry and of Other Procedure Under

Military Law 158.

18 War Department: Annual Reports, 1918, Washington Government Printing Office

(1919) 237.

19 Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy For the Fiscal Year, Washington

Government Printing Office (1918) 448.

20 War Department: Annual Reports, 1917, Washington Government Printing Office

(1918) 173.

21 "Deserters Story Stirs Army Officers: Rigid Investigation Ordered of

Abuses in the Service Described in a Magazine Article. Seek to Trace the Author:

Man Who Gave Millard His Information Thought to be Member of a Prominent Family." The

New York Times 2 Jan. 1911.