THE ROAD TO FREEDOM WAS PAVED IN SOUL

by Travis Vertuca

Keep that beat rolling and keep those feet moving. Music can stir the soul and ignite a fire, surpassing distance and moving generation to generation. Time and again the drums have been struck, the strings have been strummed and the voice has been heard. Between the shadow of slavery and the world of today, African Americans and their music have spoken to the nature of the human experience. This music has evolved, yet remains to reflect upon the shape of American thought and culture. During the 1960's, R&B and Soul captured the minds of the youth and strived to achieve social change.

THE BEAT OF EVOLUTION

Rhythm has been the means of expression since the first caveman beat on rocks.

The beat is what drives emotion, and emotion is what drives the body. Songs

can be an article of history, or can relate to modern times, but all in all,

the song has always been there. As language formed, tone and pitch taught the

voice to act as an instrument. Walton states a heightened musical sensibility,

the result of tonal language and education to pitch value, was readily transferred

to instrumental music and in some cases led to 'talking' instruments - drums.1

As with language, music varies with geography and certain scales and tones

are more common in certain areas. When slavery cast its shadow upon Africa,

a new music made a transatlantic voyage and came to the United States. At first

African music was outlawed by slave owners, but the oppression could not stop

the slaves from singing and eventually making their own instruments (it is

said that during this inventive period the banjo was born).

Our story takes us from the perils of the Atlantic to the soil of the southern

states. The heart of soul was anchored in the sweltering heat of the delta

blues. In terms of stanzas and bars, soul music is a derivative of blues. The

chords and structure are nearly identical, as is the lyrical content (a standard

three-line stanza followed by a musical response).

Slavery had ended but left the oppression and the ex-slaves had become the

lower class. New means of inhumanity swept through the south and passion of

melody was beginning to expose itself. The smuggling of music was made possible

by the conversion of pain and frustration into code, thus confusing outside

listeners, allowing the slaves to speak their minds without repercussions.

Ortiz Walton, author of Music: Black, White and Blue describes the blues as

a representation of collective yearnings and feeling, but the personal life

of the Artist becomes the prototype of the collective. Thus one of the principal

features of African music, collective representation, was preserved while the

form and apparent content changed.1

Blues started in Louisiana and Mississippi as a means of expression for African-Americans.

Although untrained, there were many musicians who formed the belt of the blues.

Usually borrowing from gospel, blues had the spirit of the working class combined

with the heartbreak of the lower class. If the music of the church was meant

for God, than blues was meant for man (and maybe the devil). For the disfranchised

citizens of the south, songs of cheating women, hard working and long hot days

were easily identifiable, keeping collective representation intact.

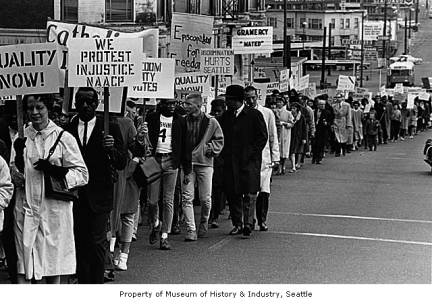

One of only two photos ever taken of Legendary Bluesman Robert Johnson

Some songs and

artists are clouded in folklore, only giving them a deeper meaning. Robert

Johnson, one of the most influential bluesman by modern standards, claimed

to have sold his soul to the devil to be able to play the guitar. His phenomenal

ability and short life span (there were only two known pictures, dead at

twenty-nine having recorded twenty-nine songs) only made him more popular.

The legends of the original bluesman traveled by word across the south. Most

seeds of the genre went unnoticed until the mid-twentieth century when the

songs were documented for the library of congress. It was discovered that there

were standard songs that traveled by word of mouth and had many different interpretations.

An example of this would be the song Country Farm Blues by Eddie James "Son" House

Jr. Considered to be prewar delta blues, House created a song understanding

of the wealth and the soul of the insolvable problems of life.

Down South, when you do anything, that's wrong

Down South, when you do anything, that's wrong

Down South, when you do anything, that's wrong

They'll sure put you down on the country farm1

Put you down under

a man they call "Captain Jack"

Put you under a man called "Captain Jack"

Put you under a man they call "Captain Jack"

He'' sure write his name up and down your back

Put you down in a ditch with a great long spade

Put you down in a ditch with a great long spade

Put you down in a ditch with a great long spade

Wish to God that you hadn't never been made

On a Sunday the boys be lookin' sad

On a Sunday the boys'll be lookin' sad

On a Sunday the boys be lookin' sad

Just wonderin' about how much time they had2

Songs spread and became anthems to the disheartened, creating a base audience

of people who were socially aware due to the morally unjust ideals imposed

by society. Music was not recorded on sheets, but memorize, often altering

its structure. These songs were the truth, they were not sugar coated (or at

least they weren't meant to be, I'm talking to you Eric Clapton) nor were they

meant for the mainstream. The songs were meant to keep hope alive, to have

something to look forward to at the end of a hard day, or to tell stories of

important values. The cotton fields, loading docks, riverboats and plantations

held within them a sound all their own. This sound was a desire to love but

only a cold and empty world to embrace.3 Sympathy for the working class was

coming. Songs were moving like winds through the south and soon would spread

across the hate that had bound them. This is how forms of art make their way

into the public eye.

THE DISC JOCKEY

In the early nineteen thirties, the disc jockeys made their unfriendly debut

into the music timeline. Beginning as a way to use the radio as a means of

a market, disc jockeys were the commentary between the songs. Over time, DJ's

took control of the song selection and were able to deem what was playable

on the radio. Far from welcome, disc jockeys were at first shunned for their

misuse of power. Performers such as Bing Crosby and Fred Waring had labels

bearing the words "NOT LICENSED FOR RADIO BROADCAST," in hopes to

deter consumers from promoting the radio. This was to become a temporary fix.

By 1935, the disc jockey took credit for the increase in sales for sponsors

as well as record sales, which had plummeted during the depression. This increase

was obviously due to the ending of the depression, but at the time the broadcast

companies saw this as a chance to make their move. After World War II, radio

attempted to captivate audience by using big names, including both Duke Ellington

and Ted Husing, to spin records. Throughout the forties and fifties, the fire

was on and the disc jockey was a controversial figure, regarded by some and

hated by others. In time, the musical selection was tamed and radio station

managers began to think of the local airwaves.

SETTLE DOWN, STREAMS OF SOUND

The dysfunction of the radio hierarchy gave the airwaves back to the public.

The people made a decision and the radio was now a means of expression. The

path of available music was ready to expand and shape the world as well as

future generations.

As the nineteen fifties came to an end, the culture line was starting to come

into focus and Rhythm and Blues emerged to become synonymous with soul. As

a faster paced, blues oriented genre, the artists of R&B realized they

were onto something. The new genre gave room for pop sensibilities to combine

with African-American culture. The message of the music was only apparent to

the creators and very aware members of the public. At first the genre was considered

to be a passing fad, but as the winds of rhythm grew stronger and louder, they

touched the souls of young white America.2 White audiences began listening

to black artists, which softened some minds during a tense time, yet also made

for some angry parents. Society deemed the youth of America was not to be dancing

to the tribal beats of African music that was Rhythm and Blues, but it blossomed

despite its bad reputation.3

After a short period of time, the record executives found there was a profit

to be made of Rhythm and Blues. Dollar value of the black consumer market rose

from $3 million in 1940 to $11 million a decade later and $20 million by 1961.4

Seeing as it was impossible to neglect the black audience, white executives

began to create rosters of black musicians. From 1955 to 1959, Mercury, Capitol,

Decca and the then recently formed ABC-Paramount were among the ten most successful

producers if black chart hits5

The link between white audiences and R&B was often seen as a rebellion

against white radio but also symbolically represented a revolt against the

social norm and expectations of the adult white middle-class as encoded and

disseminated through church, school and the work place. To listen to R&B

required a certain amount of enterprise and individualism according to the

white consensus and it was considered common for "deviant" lifestyles

to form around the genre. White teens traveled to the other side of the tracks

to hear musicians outside of the dominant culture, but eventually imitations

of soul found their way into the white mainstream.

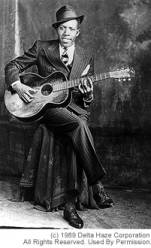

White

Audiences Dancing to R&B

White singers

began to use songs performed by black artists in an attempt to "legitimize" and attract the white audience. These imitations

as a whole varied with geography, class and gender developing into a conventional

set of white stereotypes about blacks and their culture. Whites habitually

reduced R&B, a richly diverse musical genre which embraced every aspect

of human experience, to the hypersexual, sensual and instinctual characteristics

they had associated with and projected onto blacks for centuries.3 For a portion

of the white audience R&B was a critique of mainstream America and class,

gender and social order, but this conclusion was made through the lens of racism

and race wars. Atlantic Records, trying to corner the black market away from

Capitol Records, cultivated a clean, well-mannered infusion of Rhythm and Blues,

fusing elements of blues alongside traditional white pop. Popular culture was

again trying to suppress black culture.

Members of the white music industry initially had hopes to lessen public concerns

by hiding the racial origins and propriety of new music styles. In 1951, Alan

Freed, a DJ for WJW-Cleveland and WINS-New York, made a deliberate attempt

to cover the origins of the recent "fad" by calling black R&B

by the name of "rock and roll." Not all society was thrown off by

this change in vocabulary, many white youths found this cynical foray of renaming

a sound reason to promote the allure of the forbidden world of black culture.

Far from being accepting of the outrageous view harbored by whites, groups

such as SNCC and SCLC were not exactly accepting of the thought of black youth

as being a rambunctious culture fit for white teens looking for a thrill. Martin

Luther King Jr. outlined his thought of modern musical trends and their similarity

to Gospel, saying the profound sacred and spiritual meaning of the great music

must never be mixed with the transitory quality of rock and roll music.6

The American songwriter had long been trying to harness the dollar value of

black people, but during the mid-1950's in Memphis, a young man by the name

of Elvis Presley would shake the box. Recorded at Sun Records, Elvis' "All

Shook Up" and "Don't Be Cruel," both written by black musician

Otis Blackwell, topped charts and captivated audiences. Retaining songwriting

credits now became a new ideal for black musicians. The market for traditional

R&B expanded yet again into a new field, and eventually black musicians

gained the ability to secure better legal protection of copyrights in order

to receive royalty payments. Although this was better than nothing, one still

has to remember that the fight against oppression still lingered in the air.

Henry Glover, a writer who provided many hits for Federal-King, found that

in 1950 publishing company who managed his songs grudgingly paid him one cent

(half of the average rate) per recorded side. After rallying for a more profitable

and fair publishing deal, Glover had increased his wage from one cent to fifty

cents, a large leap for blacks in the music industry.

THE BRITISH INVASION

The year 1964 brought in visitors from overseas. The Beatles had begun to make

their way into American culture and, along with many other act from abroad,

crossed the Atlantic to serenade the states. The refreshing side to the British

invasion was the broadening of American societal construction into the global

scale. White youths were again listening to music that was inspired by black

R&B, but this time the performers encouraged white American exploration

and patronage of black music as opposed to reforming and recording black songs

to fit the white stereotype. Along with the Beatles, many other prominent foreign

groups of the 1960's, including Them and The Animals, cut their teeth on traditional

Rhythm and Blues. High priestess of Soul Nina Simone noted that her travels

in Europe resulted into her discovering children and youths playing and singing

Negro Rhythm and Blues.4 Receiving credit and respect from abroad was a drastic

difference from the attitude of white America.

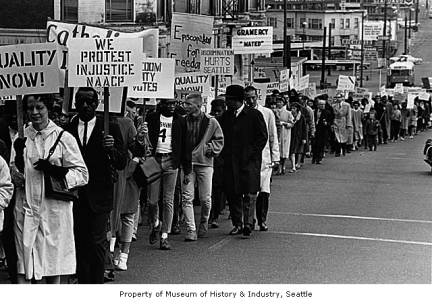

On one level, progress was being made with national media covering a genre

created by black culture, yet on another level a radical change with law making

officials was progressing. Transforming equal rights into a national issue

against federal authorities was an uphill battle. Legislation slowly made its

way through the government and tension was rising. Society was beginning to

reach is limit as brother was set against brother. The heat of the summer boiled

the blood of the movement a change was soon to be on its way. In June of 1963,

President John F. Kennedy first publicly advocated his civil rights legislation,

creating a frenzy of emotion that spread like wildfire.

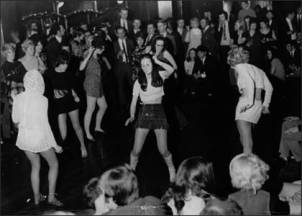

Sam Cooke Performing in 1962.

A CHANGE IS GONNA COME

On September 16th, 1964 a new program made its debut on the ABC television

network. Entitled Shindig, this was a show that premiered shortly after Billboard

had published an article explaining that rhythm and blues was on its way to

the grave. Shindig was based on the studies of interracialism amongst audience

as well as artists, and became a product and a reflection on both black and

white cultures. A long list of rhythm and blues acts graced this stage, but

its debut performer caught the eye of the public.4

Figureheads of the black pop era emerged slowly but surely. Male R&B balladeers

such as Gene McDaniels, Sammy Turner and Wade Flemons started to record in

a much more soulful vein, presenting the radio with a new avenue for black

performers, but the key singer in this era was the one and only Sam Cooke.

A crossover from Gospel, Cooke initially found himself to be a pop singer who

appealed to white audiences. Hits such as "You Send Me" climbed the

charts and with the help of (obnoxious) white studio producers, Sam gained

a base white audience while also appealing to black culture. Many songs graced

the black R&B charts and few made a marks on the pop charts, yet it was

not his early songs but rather his persona that made him a star. Considered

to be one of the most influential black artists of the time, Cooke gained more

control of his career his professional peers, white or black. With the partnership

of his road manager Cooke founded his own publishing company (KAGS), Production

Company (Tracey) and two record labels (SAR and Derby). Using his enterprise,

he signed only black recording artists to his label in order to give adequate

royalties and provide a better means of production outside the dominant white

spectrum.

Up until his death in late 1964, Cooke had not been publicly associated with

the civil rights movement, but with the release of his song "A Change

is Gonna Come," Sam made his way into the public limelight with his civil

response to Jim Crow laws and oppression in America.7 Reflecting on the inevitability

of change in the roles of black in society, this song was a direct look into

the inner turmoil of Sam Cooke as a recording artist as well as a black man

in a white man's world. 8

I was born by the river in a little tent

Oh and just like the river I've been running ever since

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change is gonna come, oh yes it will

It's been too hard living but I'm afraid to die

Cause I don't know what's up there beyond the sky

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change is gonna come, oh yes it will

I go to the movie and I go downtown somebody keep

Telling me don't hang around

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change is gonna come, oh yes it will

And I say brother help me please

But he winds up knockin' me

Back down on my knees

There been times that I thought I couldn't last for long

But now I think I'm able to carry on

It's been a long, a long time coming

But I know a change is gonna come, oh yes it will 9

The second to last verse was originally edited for radio broadcast because of its social implications, but was reintroduced for the record. This song was a departure from Cooke's previous work. Upon recording it, Sam Cooke decided that it was necessary to release, casting away concerns of losing his white fan base. Although only peaking at #34 on the Billboard charts, the exposure of this song reached as far as The Tonight Show. The song's moderate success on the pop charts was only a footnote to its success. Appearing in many films and the subject of many articles, "Change" is best known for its appearance as an anthem for the civil rights movement as well as acknowledgement by Rolling Stone as #12 on the magazine's 500 Greatest Songs of All Time list. 10

KEEP THAT BEAT ROLLING

The chain of evolution can't be deterred, but the soundtrack that accompanies the progression of the masses will also keep the spirit alive. Throughout history, art and culture have been the creative outlets that become the social commentary. From the science of language to the raw emotion of blues, the song can capture a time and allow future generations to understand a movement. The youth of America may not fully understand the turmoil and oppression that dominated the 1960's, but by using a progressive lens, not set on race and stereotype, it will be possible to appropriately view the work of musicians and artists who were the flag carriers for black culture. If you can hear the beat created by the footsteps of a march, progression can't be too far ahead.

1 Walton, Ortiz. Music: Black,White and Blue. W. Murrow. New York, NY. 1972.

A sociological survey of the use and misuse of Afro-American music.

1 Walton, Ortiz. Music: Black,White and Blue. W. Murrow. New York, NY. 1972.

A sociological survey of the use and misuse of Afro-American music.

2Eddie James "Son" House

Jr. Country Farm Blues. Alan Lomax. Library of Congress. 1941

3 Redd, Lawrence N. Rock is Rhythm and Blues (The Impact of Mass Media). Michigan State University Press. 1974.

4 Ward, Brian. Just My Soul Responding. University of California Press. Los

Angeles, CA. 1998.

5 New York Times, 28 January 1978, pp. D2-3. George, Death of Rhythm and Blues,

p. 157.

6 M.L. King, "Advice for Living," Ebony

(April 1958), p. 104.

7 Guralnick, Peter. Dream Boogie:; the triumph of Sam Cooke. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company, 2005.

8 Werner, Craig. A Change is Gonna Come: Music, Race and the Soul of America.

Plume. New York, NY. 1999.

9 Cooke, Sam. "A Change is Gonna Come."Keep Movin' On. New York:

Tracey Records, p 2001.

10 Wolff, Daniel

J., S.R. Crain, Clifton White, and G. David Tenenbaum. You Send Me: The life

and Times of Sam Cooke. William Morrow & Co. Chicago,

IL. 1995.