Adam

Lawrence

FROM WOODY TO WOODSTOCK

There

was a rhythmic clatter that a man came to appreciate when he spent his days

hitching rides on railroad freight cars. A guy could set his watch by it, if

he could afford one. He could imagine it was an active voice in a conversation

that kept him company while he tried to quiet the voice that kept demanding,

“What went wrong?” For one man, the clacking served as a metronome,

keeping time as he wrote literally hundreds of songs, each one a perfect snapshot

of life in the worst depths of the Depression.

In

1969, on a dairy farm in upstate New York, another cadenced tone dominated the

ear. It wasn’t music, but rather the blades of a helicopter flying in

musicians from several miles away because the tiny highway leading to the site

of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair was choked with cars and only allowing foot

traffic. Somehow, the twenty-somethings who were in charge of the affair wrangled

a chopper to fly back and forth to the hotel where the acts waited for news.

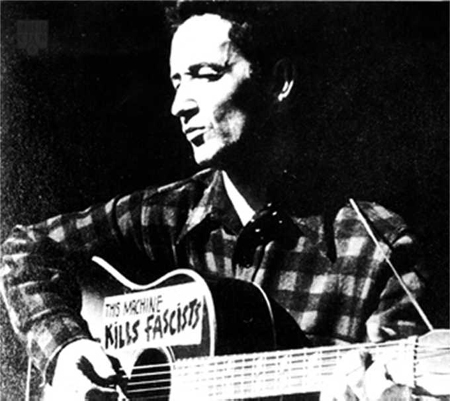

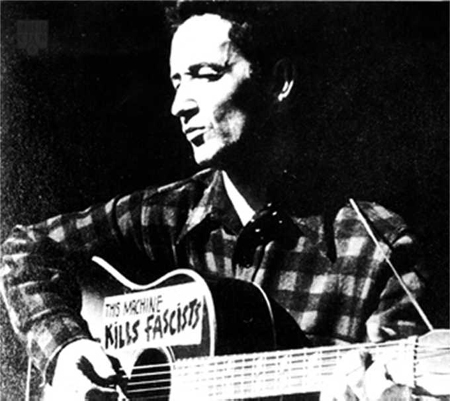

There’s

a certain pull from these cultural touchstones that is unlike any other. Woody

Guthrie is our last real cowboy, only he never shot Black Bart in front of the

saloon for stealing his horse. Guthrie is closer to the townsfolk, wearing a

white hat for exploited labor and the downtrodden. Instead of six-shooters,

he sported a guitar with the words “This Machine Kills Fascists”

scrawled along the bottom. He was astoundingly prolific, penning somewhere around

1,000 songs, each able to be sung by anyone. His catalog is the stuff of Americana

– “This Land Is Your Land,” “So Long, It’s Been

Good To Know Yuh,” “Dear Mrs. Roosevelt,” ”Roll On Columbia,”

“Do-Re-Mi,” “Pastures of Plenty,” and “Tom Joad.”

Woodstock

is another story. Originally intended to be a large showcase for up and coming

rock bands in 1969, it became a much bigger occurrence than its organizers could

ever have imagined. For four days in August, 1969, an estimated crowd of 300,000

to 450,000 people occupied Max Yasgur’s farm while the outside world watched

with bemused smiles on their faces. For those few days, a generation was certain

that a great battle had been won, their cause was fortified and Bethel, New

York was their capital. What emerged out of this particular weekend was the

idea of Woodstock as much less than a concert, but rather a final gasp of idealism,

holding music that Said Something above all other forms of social expression.

Its roots spread far and wide, but the turn of the century was the most fertile

ground for the most important players.

What

binds a Dust Bowl songwriter and a hippie utopia together is not just the music,

the idealism, or the vibe. Although they would never know it, the Woodstock

concertgoers were participating in the last gasp of socially relevant music.

1969 meant many things in the decades afterward, but by the end of the year,

Vietnam was bloodier than ever, Nixon was beginning his first term, and a mirror

festival on the West Coast named Altamont ended in murder and confusion. Those

four days in August meant more to anyone who believed in the power of music

than any single event since.

By

the end of 1970, four protesters on the campus of Kent State University were

shot dead by the National Guard, the secret war in Laos was uncovered, the Beatles

released their final album, and Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, both predominantly

featured in the previous year’s festival, were dead. To say that 1970

brought huge changes to the relationship between music and social movements

would be quite an understatement.

The

last great protest song of the golden era was “Ohio”, a biting indictment

of an American president written by a Canadian. “Tin soldiers and Nixon’s

coming / We’re finally on our own / This summer I hear the drumming /

Four dead in Ohio.” Neil Young was an auxiliary member of the late 60’s

supergroup Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. They had performed for the first

time in front of the Woodstock audience to close the third night. For many,

their set was a coda for the festival. Thousands flocked out by the time Hendrix

closed the festival the next morning.

All

four members of the group were stalwarts in the folk-rock movement of the late

60’s. Both Young and Steven Stills were members of Buffalo Springfield,

whose “For What It’s Worth” could be the prime example of

the pop protest song. Graham Nash cut his teeth in the Hollies, a British Invasion

band with many hits, and David Crosby provided the pitch perfect harmonies in

the Byrds. Once Ohio hit the airwaves, just one week after the killings, it

quickly shot to #14 on the charts. It would be the last time in 18 years the

quartet would release new music.

Similarly,

it would be the last time a song based on American atrocities would do so well

on the charts. The last notes of the Woodstock nation would never again sound

so loud. The golden age of American folk/folk-rock/protest music was over.

Six years later, a small movie was released starring an aging David Carradine

as Woody Guthrie in a cinematic treatment of Guthrie’s autobiography,

Bound For Glory. Guthrie was 10 years dead, but it gave a nation an opportunity

to re-examine its roots.

Born

in 1912, on a tiny Oklahoma farm, Woody Guthrie was a product of his times.

His full name, Woodrow Wilson Guthrie, came from a presidential candidate, a

man who would later be a wartime president. Wilson was the last of a dying breed

of progressive politicians. After World War I, Okemah, Guthrie’s hometown,

experienced an oil boom after the discovery of the crude in Oklahoma. Although

this meant prosperity for the little town, it would not last. Guthrie’s

family would soon plummet with the rest of the country into the Depression.

When

Guthrie was born, Joe Hill was in the middle of his prolific career as a Wobbly

Union songwriter. Hill became a legendary figure, with a reputation of being

at every single Wobbly meeting. He certainly wasn’t able to accomplish

such a feat, but his songs became synonymous with the movement. As a Swedish

immigrant who experienced the poor working conditions in American factories

first hand, Hill made an excellent poster child for the Everyman, the same ideal

figure the Industrial Workers of the World needed to increase membership and

sustain the possibility of “One Big Union”.

Hill

understood the power of song over the printed word from the beginning. In a

letter to a friend, Hill wrote, “A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never

read more than once. But a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over.”

Hill’s songs never reached beyond the converted, predominantly featured

in the Wobbly Little Red Song Book, and he’s most famous for two things:

coining the term “pie in the sky” in his song, “The Preacher

and The Slave,” and his death as a convicted murderer in Utah in 1915.

His death sentence even drew the attention of Woodrow Wilson, who urged clemency

for Hill with Utah Governor William Spry. Wilson’s request was denied

and Hill was shot to death in front of firing squad on November 19, 1915.

Hill’s

body was quickly shipped to Chicago for a funeral. Over 30,000 attendees lined

the streets to mourn the IWW’s most visible member. The murder he was

convicted of never really escaped scrutiny, but it was Hill himself who sealed

his own fate. His decision not to testify in his trial, a circus from the beginning,

meant that Hill would forever be remembered in death. His final words telegraphed

to IWW President “Big Bill” Haywood were, “Don’t mourn,

organize!” Woody Guthrie was three years old.

Guthrie’s

childhood is a marked by remarkable suffering. His father was a real estate

speculator, successful in his early days, but later, during the Oil Boom, more

cut-throat speculators moved in and destroyed his business. Woody’s childhood

home burned down within a month of being built. It would not be the last fire

to touch the Guthrie family.

Woody’s

sister, Clara, set her clothes on fire in order to get back at her mother for

keeping her home to help with housework. She intended to give her mother a fright

and then put out the fire, but of course the flames had other ideas. She was

consumed and died the next day.

Woody’s

mother, Nora, suffered from Huntington’s chorea, a disease of the nervous

system which manifested itself in bizarre behavior, eventual loss of control

over one’s body, and eventual death. After a series of financial failures,

Nora Guthrie set her husband, Charley, on fire. He survived and Nora spent the

rest of her life in an asylum, dying in 1929. Nora Guthrie was an indelible

influence on her son’s life. He frequently sat at her feet while she played

songs at the piano. It was because of her that his musical interests were cultivated

from a very early age. And mother and son would both die early under the cloud

of a very macabre disease.

Once

Nora was institutionalized, Woody’s father decided to relocate to Texas.

In Texas, Woody began his first band, the Corncob Trio, in which he played with

the brother of the woman who would later become his wife. When the Dust Storm

hit in 1935, Woody went west, encountering the same hardship Steinbeck wrote

about in “The Grapes of Wrath”. This was a fruitful time for Guthrie,

however, as his travels gave him the opportunity to pick up songs from all over

the nation, indeed the world, as many men who rode the rails and lived transient

existences brought songs with them. Woody’s repertoire grew.

He began to appear on the radio, delighting farm workers who had settled in California, with his songs. Soon after his radio success, Guthrie fell in with the Communist party, a suitable home for a man who was disillusioned with concepts like private property and the continuing exploitation of the American labor. Eventually, the Party tried to take advantage of Guthrie’s growing fame, hoping to attach his name to their cause. Woody replied, “Left wing, right wing, chicken wing…I don’t care as long as I get to sing my songs. “ It was this very statement that defined Guthrie’s attitude toward organized political parties and authority figures. Woody didn’t work for people, he worked for causes and in 1940, he signed on to perform at a benefit for the John Steinbeck Committee of Agricultural Workers, also known as “A Grapes of Wrath Evening.”

It

would take a music historian from New York to bring Woody to nationwide attention.

When he and his father scoured the American landscape to find musicians and

styles largely ignored, Alan Lomax made the first ever recordings of Woody Guthrie

in 1940. In association with the Library of Congress, the Lomaxes became the

preeminent force behind field recordings and a nationwide re-awakening of the

folk music tradition. Among the Lomax discoveries were Leadbelly, Cisco Houston,

and scores of obscure blues musicians buried in obscurity in the south.

Guthrie’s recordings would become the backbone for the folk movement of

the 50s and 60s. The sheer volume of songs he wrote would go on to fill out

the pages of Broadside, the folkie bible of songs and news within the folk community.

Folk acts were always part of the landscape, but Guthrie, with his down-home

colloquialisms and relaxed attitude, really became a kind of folk hero.

He

had survived the Dust Storm, he couldn’t be tied down, and he tasted financial

success near the end of the depression and told the fatcats to stuff it. He

lived life on his own terms, providing a sometimes contradictory picture. He

ardently supported the communist party, yet refused to renounce his religion

in order to officially join their ranks. He sang of utopian left wing ideals,

yet served in the Merchant Marines and even the regular army at the end of World

War II. He wrote and sang scores of children’s songs, yet left many the

scores of his own children neglected and without a father. And for many Americans,

Woody is the author of one of the most patriotic songs ever written, “This

Land Is Your Land,” but few schoolchildren have ever heard the ardently

left leaning lyrics of the later stanzas. His greatest success was enjoyed after

he was long debilitated by Huntington’s Chorea, the very same malady that

killed his mother. But without him, the music of the 50’s and 60’s

might not have been as ground shaking or as important as it proved to be.

The

Lomax recordings of the early 40’s began a renewal in American folk music

that would continue for nearly two decades to follow. For many, the folk revival

was little more than a larger interpretation of campfire sing-alongs. There

was a willing and able commercial demand, though, for traditional songs played

by non-threatening artists who could capture the original spirit of the folk

tradition. The songs that were prominent in this wave were based on gospel songs,

spirituals, and centuries old European tunes brought over by millions of immigrants.

Acts like Joan Baez, Judy Collins, Burl Ives, Mitch Miller, and The Almanac

Singers were noticed by the record buying public who acquiesce to the rising

tide of Rock n’ Roll.

For

the most part, folk acts were clean cut white people who took cues from the

black roots of Blues and Gospel music. Soon, the folk tradition was adopted

by the rising tide of college protesters who demonstrated against the Vietnam

War. Early footage of the free speech movement at campuses in Madison, Wisconsin

and Berkeley, California featured fresh-faced white kids in shirt sleeves, ties,

and horn rims singing spirituals like “All My Trials” and “We

Shall Overcome”. Folkies were derided as chronically out of touch, innocuous

and naïve, hoping to change the world with an acoustic guitar and sweater

vests. The story of the Weavers illustrates the contradictory universe in which

folk musicians lived.

Pete Seeger was a child of musical and radical parents. His mother trained at Julliard, his father was an administrator at Berkeley at the turn of the century. By the time he met Woody Guthrie, in 1940, Seeger was a veritable folk music historian, able to whip out any song requested of him. He was also a staunch communist. Years later, he was the backbone of the Weavers, a hard-working authentic folk band that wowed crowds in the clubs who were tired of the same old stories. Each member had dabbled in communism, but when the gigs kept selling out, and the record contracts were signed, their politics never once found its way into their act. In fact, it was almost as though a conscious decision was made to sterilize the group for easy consumption. Their most popular songs, “Goodnight Irene”, “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine”, and “Wimoweh” could hardly be called subversive.

Yet

as their success grew, and the records sold, McCarthyism took root in the American

psyche. Soon the Weavers’ past would destroy their reputation. The CIA

put them on their watch list and the records stopped selling, the bookings dried

up and four years after they formed, and despite their best efforts to keep

their politics away from their image, the Weavers broke up. In their attempts

to straddle the line between the left and right wings, they had alienated their

communist brethren and had agitated the right wingers who were sniffing out

every last communist party member who ever existed.

A

few years later, after Vanguard Records became the preeminent folk music label,

the Weavers were reunited and gave a shot at recording again. Their reunion

concert was released in two volumes and sold very well, exposing new fans to

their music after McCarthy had been exposed as a paranoid paper tiger. It was

1955 and the Weavers had a new lease on life. They lasted well into the 60’s,

although never reaching the success they enjoyed in their early days. Clearly

there was a sea change – eventually the Weavers became subversive despite

their best efforts and were being hailed in much the same way that Woody Guthrie

was. They survived the witch hunt of the McCarthy era, only by breaking up and

riding out the storm. Their offspring, bands like the Kingston Trio, Peter,

Paul & Mary, and the Limelighters were able to build upon their legacy and

become part of the wave of progressive movements of the 60’s. Pete Seeger

would continue to perform well into his 80’s, just as true to his convictions

as ever. Beyond his best known song, “Where Have All The Flowers Gone?”,

Seeger was instrumental in bringing the world’s attention to a 20 year

old Guthrie acolyte from Minneapolis.

By

the time Robert Zimmerman hung up his red James Dean jacket headed east to New

York City in 1960, he had discovered the music of Leadbelly, Odetta, and above

all, Woody Guthrie. Dylan devoured Woody’s autobiography, Bound For Glory,

and he changed his focus from being the second coming of Buddy Holly to worshipping

at the altar of Guthrie. He dressed like him, sang like him and, after dropping

out of the University of Minnesota, headed east to New York City to visit his

idol in the Brooklyn State Hospital. In the years that followed, Zimmerman changed

his name to Bob Dylan

and became the most famous folk singer/songwriter in the burgeoning folk scene

in Greenwich Village. To the faithful, he was little more than a Guthrie impersonator,

using the same high nasal singing style Woody was forced to adopt when performing

without amplification. He shamelessly sang Woody’s songs, occasionally

sprinkling his own tunes into the set. Before he became famous, Dylan frequently

visited Guthrie in the hospital on many occasions. Wracked with disease, Guthrie

had long since given up recording and performing, but he still wrote plenty

of songs.

Being around his idol and mentor gave Dylan even more confidence to pursue his

own songwriting. More and more of his songs made the pages of folk music magazines

like Sing Out! and Broadside Ballads, sometimes even before Dylan had a chance

to record them himself. Such was the case with “Blowin’ In The Wind,”

an old school folk ballad of the highest degree. Before it was a landmark tune

that would become the pinnacle of the 60’s folk revival, it was simply

a page of typewritten lyrics in a folk music magazine. By the time Dylan released

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan in 1962, gone were the traditional ballads

that filled out his debut. Instantly, Dylan became the top songwriter in any

genre. Two acoustic folk albums followed, including The Times, They Are A-Changing,

and Another Side of Bob Dylan. At the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, Dylan and

the Butterfield Blues Band brought out electric instruments and amplifiers and

“plugged in,” changing the face of rock n’ roll forever. There

are many secondhand accounts of that day, not least of which is Pete Seeger

trying desperately to find the power switch, all the while holding his ears

in pain. Dylan didn’t play his best set that day. In fact, the band suffered

for being woefully unrehearsed. This doesn’t change the myth of the day,

the one that has Dylan deliberately dismantling the status quo, knowing exactly

what would happen. Dylan’s first single for Columbia Records in 1962,

“Mixed-Up Confusion,” featured an electric backing band. Also, Dylan’s

Newport set was preceded by the release of Bringing it all Back Home, an album

with an entire side of electrified songs. Surely, Newport was simply the natural

progression of Dylan’s career.

Regardless

of whether or not it was to be expected, the folk community ate Dylan alive,

claiming he had used them all the while on a crusade to become a rock star.

Dylan spoke of simply becoming tired of being asked what he stood for, choosing

instead to go where his music took him. From 1965 through 1966, Dylan released

three classic rock n’ roll albums (Bringing It All Back Home, Highway

61 Revisited, Blonde On Blonde), calling all his own shots and shattering expectations

of what rock n’ roll mixed with some folk ideals could do. As the counterculture

began to emerge, Dylan became their patron saint, supplying the emerging hippies

with lines that could be uttered with a few questions about hidden meanings.

In “Ballad Of A Thin Man,” Dylan sings of Mr. Jones, a completely

out of touch Man in a Gray Flannel Suit who just doesn’t understand the

world around him - “Something is happening here/but you don’t know

what it is/Do you Mr. Jones?” “Like A Rolling Stone” asks

“How does it feel/To be without a home/With no direction home?”

And “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35,” which referenced the drug scene

and told of being hassled by The Man – “They’ll stone you

when you’re trying to be so good/They’ll stone you just like they

said they would/But I would not feel so all alone/Everybody must get stoned.”

Dylan

blazed his own trail, never conforming to the authority figures who said he

wasn’t a good enough singer to be popular, was too heady to get on the

radio, or too ambitious for his own good. In 1967, Dylan was riding his Triumph

motorcycle at his home in Woodstock, NY. He hit a rock in the road and took

a header over the handlebars. He remained in critical condition for a week.

Dylan’s friend Richard Farina had died a year earlier in a similar fashion.

Dylan would stay a recluse for several years, content to let speculation swirl

around his condition. He wouldn’t tour again until well into the 70’s.

In 1969, something would happen to make the myth of Woodstock would grow larger

than ever.

The

Woodstock Festival was originally supposed to be a celebration of the Woodstock

Nation. In years prior, the small town that had long been an artist’s

hideaway had several high profile residents. Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Janis

Joplin, Van Morrison, Tim Hardin, and the Band had all moved there, and the

town had a rich history of art schools that fostered the image. Four men from

lower New York, two of whom were independently wealthy, would transform the

name of the city to become synonymous with the hippie movement in an attempt

to blend unabashed capitalism with the counterculture movement of the late 60’s.

All

of the four principle names behind the festival were quite young. The oldest

among them was 26 and each man, Artie Kornfeld, John Roberts, Michael Lang,

and Joel Rosenman, possessed the requisite youthful hubris needed to pull off

what would become the largest rock festival of its time. Roberts had the money,

being a trust fund heir to a large toothpaste fortune, and he and his friend

Joel Rosenman originally wanted to be television writers. Lang was the manager

of a marginal rock band and Kornfeld was a hip executive at Capitol Records.

Together they began to think big.

Lang had been at the Miami Pop Festival, a two day event that was the largest

concert of its kind with 40,000 attending. All the men had appreciation for

Bob Dylan and they all knew he lived in Woodstock, New York. They envisioned

an outdoor festival that would fill a summer, like the folk festivals of the

early 60’s. Using connections within the industry and previously unheard

of payouts, they soon had a roster full of late 60’s folk artists, California

rock bands, and up-and-coming unknowns. They had enough to fill four days, they

just had to find the land.

Woodstock,

New York was always the intended site. About 100 miles north of Manhattan, it

provided the pastoral, back-to-nature image the guys were looking for. There

was talk of building a recording studio with the money made from the festival,

then described as a “party” . Soon the numbers grew and the Woodstock

Ventures Inc. partners set out to procure a site.

For

$10,000, they could have had their Woodstock site. Lang vetoed it, saying “the

vibes weren’t right. It was an industrial park.” Soon the focus

shifted to a town called Walkill, just off of a major highway and zoned for

large exhibitions. Soon, however, the locals urged the zoning board to ban large

concerts in their city limits. Woodstock Ventures once again was forced to look

for a home.

They

still needed the country setting – ads had been promising it in major

newspapers and radio stations nationwide. A resort owner from Bethel came to

the rescue, offering to talk to his friend Max Yasgur, who owned a dairy farm.

Woodstock Ventures assured Yasgur they expected 50,000 attendees tops. For $75,000

they rented the 600 acres By the time the permits went through, the Festival

was going to happen, whether they had the right paperwork or not. They were

just cutting it too close. The stage needed to be built and somehow they needed

to build a sound system that would be heard by hundreds of thousands, an unheard

of feat. Plus, the Hog Farm and Merry Prankster communes had been recruited

to bring as many people as possible to the site. A lawsuit was filed a week

before the festival, but it was settled by the promoters agreeing to add more

portable toilets. A small faction of the townsfolk organized a human chain to

block the roads, but concertgoers started coming in the night before. Woodstock

was going to happen, and no one really knew what to expect.

The

only people who paid for Woodstock had bought advance tickets. The rest just

showed up. Ticket booths had been left until the last minute and by the time

people arrived in earnest, the organizers could only get two or three in place.

Not only that, but the concessionaires, Food For Love, quickly realized they

were in over their heads, the state police refused to help with traffic, and

security officers from the city were ordered by their chief to return to work.

By the time the first hundred thousand attendees were in the grounds, the hired

ticket takers were trying to get everyone to leave and come back through so

they could get their tickets. Wavy Gravy, the leader of the Hog Farm in San

Francisco, decided that was the time to take the fence down. Soon, Michael Lang

found his way to the house mic and stated the obvious, “It’s a free

concert from now on.”

Richie

Havens was the first performer that day, really because he was the only one

who was ready. The day’s acts were spread out miles from the site in hotels

and the contracted helicopters hadn’t arrived yet. Havens was a well-known

holdover from the Greenwich Village days and had plenty of songs that the crowd

would know, like “Handsome Johnny” and “Just Like A Woman.”

Around the third hour, he ran out of songs and improvised “Freedom”,

which was reminiscent of “Motherless Child,” an old spiritual. He

left the stage to wild cheers.

The

helicopters still hadn’t arrived with the scheduled bands, so a tripping

Country Joe McDonald was recruited to keep the audience from getting bored.

He walked out to the middle of the stage and yelled, “Gimme an ‘F’!

Gimme a ‘U’! Gimme a ‘C’! Gimme a ‘K’!”

then launched into “I Feel Like I’m Fixing To Die Rag” an

antiwar ditty that had been around since 1966. It was perfect satire for the

times – “Well come on mothers all throughout the land/Pack your

boys off to Vietnam/Come on fathers don’t hesitate/Send ‘em off

before it’s too late/Be the first parents on your block/To have your boy

come home in a box.” The crowd was used to hearing the song as a full

on psychedelic band experience, but McDonald was pushed onstage with a borrowed

guitar and a matchbook for a guitar pick. Nevertheless, the ever growing crowd

ate it up. McDonald’s side comment during the song showed everyone what

the ultimate goal of gathering so many kids in one place – “Listen

people, I don’t know how you expect to ever stop the war if you can’t

sing any better than that!”

Soon

the rain started to fall. Joan Baez closed the night well past midnight during

a driving thunderstorm. Five inches of rain fell within three hours, but Baez

braved the weather to sing a song from days gone by. Before she ended her set

with “We Shall Overcome”, she talked about her husband, David Harris,

an antiwar activist who was jailed at the time for evading the draft. Instead

of taking on the war head on, Baez chose to sing one of Harris’ favorite

songs, which she introduces as an “organizing song.” It was written

as a poem in 1930 and included these lines – “I dreamed I saw Joe

Hill last night/Alive as you or me/Said I, ‘But Joe you’re ten years

dead’/’I never died,’ said he”

Joe Hill lived on in the Woodstock Nation, his legend retold to thousands of

twenty-somethings who probably had no idea who he was. Perhaps this was the

culmination of the Joe Hill mystique, used to provide a link to the past for

an estimated “half a million strong” who needed a leader in the

wake of recent assassinations of King and Kennedy. Who knows what Baez meant,

if anything by resurrecting the long-dead union leader. Perhaps she was moved

by the sheer numbers, or the growing feeling of community that took over the

festival in the early hours. There was a sense that those at Woodstock were

part of a Happening, a counterculture revolution that showed that hundreds of

thousands of like-minded people could gather in one place, under a common thread

and at least feel like they were accomplishing something.

Woodstock artists understood the value of the gigantic stage on which they were

playing. It was a perfect time to get out the message, and predictably, there

were plenty of anti-establishment sentiments expressed on the stage.

Jeffery

Shurtleff joined Joan Baez on stage for a condemnation of then Governor Reagan,

before launching into “Drug Store Truck Driving Man.” There was

of course Country Joe and the Fish, Richie Havens’ “Handsome Johnny,”

Sly and the Family Stone’s “I Want To Take You Higher” and

on and on. Perhaps the moment which perfectly set up the tenuous blending of

politics and rock n’ roll came during the Who’s set. They were performing

“Tommy” in its entirety when Abbie Hoffman stormed the stage and

grabbed the mic, and angrily proclaimed, “I think this is a bunch of shit,

while John Sinclair rots in prison.” That was all Hoffman was able to

get out before getting whacked in the head by Pete Townsend’s guitar.

At that very moment, rock n’ roll and politics forever splintered.

Woodstock

would go on for four total days, ending on a Monday morning with Jimi Hendrix

playing to a thinned out crowd. He also provided one of the most memorable moments

– a tripped out and nearly unrecognizable version of “The Star Spangled

Banner” which provided a nice exclamation point to the festival.

Just

110 days after the festival ended in Bethel, the Rolling Stones tried to do

the same thing on a speedway in California. The lure of creating another Woodstock

was too great, but unfortunately Altamont was even less organized than Woodstock

ever was. Woodstock got by with 150 volunteer police officers for security.

Altamont hired Hell’s Angels, and paid them in beer. The Aquarian ideal

lasted less than 4 months.

A

year later, Woodstock Ventures had splintered and both factions were suing each

other. It would be years until the corporation ever made money. If not for the

semi-wild idea to film the whole thing, Woodstock may never have made money.

There was more myth surrounding the festival than fact it seemed in the decades

that followed. Yes there was one, one child born at Woodstock. Most of the sets

at Woodstock were fair at best. It was, after all, a makeshift venue with a

poor sound system. The estimated crowd in attendance varies anywhere from 150,000

to 700,000. It wasn’t even in Woodstock, NY. But for all its flaws, its

hear was in the right place, and if the 4 guys from Woodstock Ventures hadn’t

done it, someone else would have. 25 years later, Michael Lang organized a 25th

anniversary show in Saugerties. It was a little more successful financially,

complete with Pay Per View and corporate sponsorships. Bob Dylan finally came

home to roost and performed an inspired set. Five years later, the Woodstock

name was attached one more time to a fated project. Charges of arson and rape

marred what should be the final Woodstock concert ever. Fans complained of outrageous

concession prices, a far cry from “breakfast in bed for 400,000”

that Wavy Gravy promised in 1969.

In

1974, “Tangled Up In Blue” was released. Five years had passed since

the last notes faded out at Woodstock. Bob Dylan sang of “Music in the

cafes at night/Revolution in the air.” The revolution that so many thought

were certain to come after 400,000 hippies gathered on a dairy farm in Bethel,

NY never happened. Nixon stayed in the White House, the Vietnam War would rage

on for another several years, and many of those who had tuned in, turned off

and dropped out had to find ways to support their new families and pay their

rent. The Woodstock nation was well on its way to becoming Yuppies.

It’s

been a while since Joe Hill and Woody Guthrie were at the top of their game.

One thing can be said about both men and the Woodstock festival – often

more myth surrounds them than fact, but each are cultural touchstones which

serve to remind us of the uniting power of music.

Works

Cited

1. Bogdanov, Vladimir, et al., All Music Guide. New York: Backbeat Books, 2002

2. Dylan, Bob. Blood On The Tracks. Columbia Records, 1974

3. Dylan, Bob. Lyrics: 1962-1985. Harper Collins Publishers, 1988

Festival. New York: Viking Press, 1989.

4. Gill, Andy. Don't think twice it's all right : Bob Dylan, the early years.

New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1998

5. Guthrie, Woody. Bound For Glory/Woody Guthrie: Illustrated with

sketches by the author; with an introduction by Studs Terkel. New York: E.P.

Dutton, 1943

6. Guthrie, Woody. Dust Bowl Ballads. 1940. Reissue. Cambridge, Mass.:

Rounder Records Corp., 1988.

7. Partridge, Elizabeth. This Land Was Made For You And Me: The Life and

.Songs Of Woody Guthrie. Viking Children’s Books, 2002.

8. Spitz, Bob. Barefoot in Babylon: The Creation of the Woodstock Music

9. Tiber, Eliot. “How Woodstock Happened.” The Times Herald-Record

1994

10. Various Artists. Woodstock: Three Days of Peace and Music; 25th Anniversary

Edition. Atlantic Records, 1994.

11. Verodia, Ken. “Joe Hill’s Story.” Joe Hill: The Man Behind

The Martyr.

http://www.pbs.org/joehill/story/index.html

12. Woody Guthrie: This Man is Your Myth: This Man is My Myth. American

Studies, University of Virginia. http://xroads.virginia.edu/~1930s/RADIO/woody/woodyhome.html

13. Young, Neil. “Ohio.” So Far. Atlantic Records, 1974:::your text

goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your

text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes

here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your

text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes

here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your

text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes

here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your

text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes

here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your

text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes

here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your

text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes

here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your

text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes

here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your

text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes here:::your text goes

here:::your text goes here:::