Fish-in for Civil Rights

by Blake Matthews

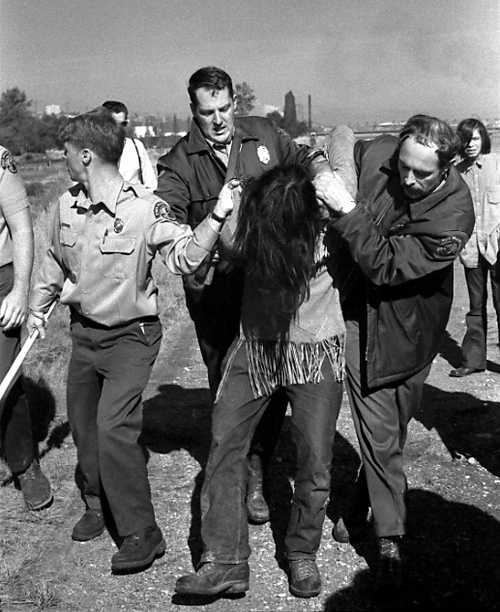

Arrests at a Puyallup fishing protest, 1970

http://www.stephenlehmer.com/puy_fish/Puy_fish_pages/Puy17pg.html

Let us take a metaphorical step back in time to perhaps six to ten thousand years before the present, the luh-shoo-seed speaking Natives, in particular, spent much of their lives on the banks of the East-side of what is now called the Puget Sound watershed, thriving from a subsistence way of life. Clean fish were caught from clean waters and were caught in ways that did not destroy the salmon populations, dam the rivers, or pollute them. However, during the 19th century bands of Puget Sound Natives were lumped together for the purpose of signing away their land in their first legal contracts with the United States: the Medicine Creek Treaty of 1854, and the Treaty of Point Elliot of 1855 being the most applicable to this paper. Furthermore, along with the colonization of the United States of Americas’ Pacific Northwest, came sometimes violent restrictions on the Native subsistence way of life. If anything positive, from the Native perspective, came from these treaties it was the guarantee of the government’s protection of Native right to fish in “usual and accustomed grounds and stations” (Morriset 2) yet, curiously enough, not in usual and accustomed methods. The violence brought against Native folks during the 20th century who were either unaware of the need to, or flatly refused to get “state fishing licenses” and follow “state seasons or take limits” (Wilkinson 30) as well as the use of the usual and accustomed methods of Native fishing, like gill nets, is curious. Time and again Natives have proven that the usual and accustomed methods of fishing were not harmful to salmon populations which, in modern times, have become threatened due, in large part, to dams, commercial fishing, and anthropogenic pollution—a stand-alone subject not addressed here. Let us take that step back in time and think about the closest approximation of the typical subsistence way of life for pre- and slightly post-contact Puget Sound Natives in order to gain a sense of their context; we will look at treaties made with Natives during the creation of Washington state, which got the Natives out of the way of Westward expansion; we will examine the controversy that surfaced, mainly, from 1964-1974 when groups of Native fishermen and their families practiced illegal fishing sometimes causing violent altercations between Puget Sound Natives, game wardens, and state law enforcement officials. Furthermore, in “Indian Country” at the least, these altercations have been called wars and should be officially and equally acknowledged in educational systems as a part of, and in its own right, a civil rights movement.

Northwest Coastal Natives of the North American continent, and the indigenous historically luh-shoo-seed speaking Salish people of the East side of the Puget Sound watershed being no exception, were and are people of the cedar and the salmon. In other words, the Northwest Coastal Natives extensively refined the use of wood, mainly cedar, into large beautifully carved fish hooks with sharpened bone functioning as the hooks’ spear-point, hand-woven lines/ ropes, carved spears, hand-woven nets, fish traps and weirs to catch abundant fish (Stewart). Cedar was ingeniously and artistically fashioned into a great many utensils like ladles, boxes, bowls, baskets, and tools—the handle for an adze, a carving tool, comes to mind—just to name a few examples. Cedar planks and posts formed the structure of longhouses, which were the common dwelling for Northwest Coastal Salish Natives. A longhouse could be anywhere from 10’ to 60’ wide and 30’ to 100’ long depending on the status of the families living there; chiefs had the largest longhouses as they had large families and did most of the entertaining. Longhouses were typically the seasonal dwellings during fall and winter; Native folks would go upriver or generally travel more to temporary dwellings during the warmer, more fruitful months for the obvious reason of taking advantage of blooming nature. The people traveled by water in cedar canoes pulled by cedar paddles to catch fish in the Sound or on the rivers, as well as to journey to another village sites for gatherings or potlaches. Cedar bark was very important and stripped from both red and yellow cedar trees in spring and summer when the sap is flowing, making it easy to separate from the tree in such a way as to not destroy the tree. Then the inner bark is separated from the outer bark and dried. Cedar bark is then processed and shredded with stone tools and oiled usually with fish, or bear oil which could then be intricately woven to form garments and hats (Stewart).

However, and once again, the importance of the use of cedar to procure fish as a primary dietary staple cannot be emphasized enough. The Natives had ingenious methods for catching fish, like creating artificial tide pools at the mouth of a river, for example. The tide would go out leaving water and fish in the tide pool and the fish were simply speared (Stewart). Salmon and other fish were trolled for while a canoe puller travelled. Bag nets were used to simply scoop into a school of fish (Stewart). A gill net, part of the controversy caused later during the fishing wars, was traditionally constructed out of braided cedar rope, weighted with rocks and buoyant from seal-skin floats.

The luh-shoo-seed-speaking Puget Salish people have mythologies surrounding salmon and their life cycle. One story in particular is “The Legend of the Humpy Salmon” told by Ray Paul at Swinomish in 1981 translated and reprinted in Vi Hilbert’s Haboo: Native American Stories from the Puget Sound. This tale tells of “an old Humpy” (Hilbert 118) salmon who is a pink or humpback salmon, aptly named because of their humped back, who begins going upriver with his young female partner who abandons him shortly after leaving the ocean due to his weakening physical condition the further he goes upriver. In other words, the further along he goes the more weak he becomes because the fresh water washes off his salt water slime and the more he becomes unattractive to female salmon. The story is unlike a typical modern American children’s tale with happy endings and rainbows, the old salmon does not make it to the spawning ground, turns around, floats back to the ocean and dies shortly after reaching the salt water. This story is a clear example of the term “traditional environmental knowledge” (Good Striker 147) cleverly disguised but usually present in the storytelling from many individual indigenous American cultures. The reality is that an aged salmon, no longer strong enough to make it to spawning grounds, or keep a mate, becomes weaker fighting the current despite his or her biological drive to do so until he or she has no other choice but to float down stream and out to the ocean where he or she passes. The point being that it is no stretch of the imagination to assert that fishing was, and still is, extremely important to the indigenous people of the Puget Sound watershed. Yet, with the appearance of non-Natives in the luh-shoo-seed-speaking Puget Salish Natives’ territory in the nineteenth century their lifestyle of the past six to ten thousand years started ending. In generations to come federally appointed treaty-makers, their papers, the increase of fenced-off and settled traditional territories and all the nuances that came along with Manifest Destiny caused the Natives much confusion, subjugation, and even harm.

Franklin Pierce was the President of the United States from 1853-1857 and encouraged the settlement of the 350,000 square miles of the newly acquired Oregon Territory from Britain (Schwantes 124). His newly appointed governor of Washington Territory, Isaac I. Stevens arrived in Olympia in November 25, 1853 (Eckrom 11). In so many words, part of Steven’s assignment as the new governor of Washington territory was to survey for railroad routes and act as an Indian agent going along “intimidating and cajoling Indian people into signing away most of their land in exchange for a variety of goods and promises” (Schwantes 125). Further shifting the power to Isaac Stevens away from the Natives was his insistent use of Chinook Jargon, “a mish-mash of French, English, and various Indian tongues. It worked well enough for the trading of beaver pelts, but it was a poor tool for something as complex as the making of a treaty” (Eckrom 4). Once again we are referring to Puget Salish Natives who spoke luh-shoo-seed which has a 46 character alphabet, and therefore, is a highly refined phonetic-language with a complex grammar system that uses around 5,000 words, unlike Chinook Jargon which employs only about 500 words all with phonemes equivalent to those found in English. Furthermore, Stevens did not negotiate any article of the Medicine Creek treaty: the first article had twelve provisions but primarily dealt with allotting tribal land away from traditional territories to be occupied by the Natives who were to reduce their “horse herds to 500 head and castrate the bulk of their stallions” (4); relinquish slaves and not take any new slaves; cease intertribal war(s); recognize the Federal Government as Native internal affairs director; cease trade outside of the U.S., namely Vancouver Island; cease using or having alcohol on reservations; recognize the right of the President to whimsically remove any band/ tribe from their reservation “to any other suitable location within said territory” (5). Article two promised $32,500 in exchange for 2,240,000 acres of land to help with starting Natives with the non-Native version of societal operations to be used for things like farm equipment, and clothing which was to be trickled out to the Natives over twenty years; or $3,500 to help with Native relocation to one of three 1,280 acre reservations; the building of free-to-children agricultural and industrial schools which the government would maintain for twenty years; “A smithy, carpenter shop, and white instructors were to be provided along with a doctor” (6). However, and most pertinent to this paper, is article three of the Medicine Creek treaty that, in Eckrom’s opinion: “has haunted whites and Indians alike down to the present day. Article three of the treaty guaranteed the Indians the right to take fish and game ‘at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations in common with all citizens of the territory’” (6; American Friends Service Committee 23-24). It is unfortunate and true that Chinook Jargon did not accurately convey complexities like “sovereignty, land ownership, fishing rights, assimilation, freedom” (Wilkinson 11).

Natives were about to be washed in the tidal wave of restriction on their ways of life, yet an “X” appeared beside any Native name on the document, forged or not. And because of the unfair treatment that Natives, shortly thereafter, began realizing that they were receiving, revolts and skirmishes began breaking out across Washington territory after 1855 between the Federal government and, primarily, the Yakamas of eastern Washington, the Snoqualmies, and the Puyallup-Nisquallys. The government acted quickly to intern some 4,000 Natives to temporary reservations on “Fox Island, Point Monroe, Whidby Island, Squaxin Island” when rumors of war spread leaving somewhere around 300 Native warriors to fight for their rights (Eckrom 44, 45; American Friends Service Committee 25).

At this time it is necessary to introduce you to a Nisqually man named Leschi as an example of the kind of controversy that befell Native people during this time. It is historically true that Leschi and his brother Quiemuth were often men of influence in their community but there is, however, controversy as to their status as tribally-recognized “chiefs” for the people; to Stevens that might not have mattered. According to Eckrom, witnesses testify that on the one hand Leschi did, perhaps arbitrarily, put his “X” next to his name on the treaty document, but there is opposing testimony that claims he refused offered gifts and refused to sign the Medicine Creek treaty on December 26, 1854 (12; American Friends Service Committee 25). The fact is Leschi was angry with the small parcels of land far removed from the Nisqually river (Wilkinson 12) and that because of his oratory skills, his diplomacy, and wisdom he was from then on seen as a leader of the Nisqually people and a trouble-maker by whites. It has not been definitively proven, however, that he was ever a warrior. Leschi led his people into the foothills of the Cascades; a conflict between U.S. Rangers and Nisqually warriors went on for eight months (15). A sad event was Maxon’s Massacre at the Nisqually village site of Leschi’s birth where the Mashel River and Ohop Creek merges with the Nisqually River. In April 1856 Captain Hamilton J.C. Maxon came across this encampment and ordered his men “to charge the defenseless Nisqually families. They slaughtered some seventeen Nisqually and wounded many more” (17). Leschi was eventually brought in to Stevens by his own nephew on charges of murder of Abraham Benton Moses. Once again testimony differs on his whereabouts at the time of Moses’ death, and Moses, a colonel on active duty, was killed during battle and was, therefore, not murdered. In any case Leschi, a well-respected man, was hung on February 19th, 1858. Leschi was officially exonerated in 2004. Surprisingly President Pierce, in 1857 expanded the Nisqually reservation to 4,700 acres that “straddled the Nisqually River” perhaps out of empathy for the government inflicted plight upon Natives, but probably more like appeasing them so they’d stop revolting (19). So what does this have to do with tribal fishing rights in the 20th century?

A context for the 20th century fishing rights wars begins in 1916 when the United States military and the city of Tacoma moved to create a 60,000 acre base, Fort Lewis, which required about 2/3 of the 4,700 acre Nisqually reservation. A Nisqually fisherman, Billy Frank Sr. was able to buy 6 acres from Wint Bennett, a local farmer, along the Nisqually river which became Frank’s Landing (Wilkinson 26-28). “By the mid-1960s Frank’s Landing, along with demonstrations led by Bob Satiacum, Ramona Bennett, and other Puyallups on the Puyallup River in Tacoma, had become the focal point for the tribal assertion of treaty rights in the Northwest…The drama at Frank’s Landing began in earnest in January 1962” (Wilkinson 34).

The Frank family, like many other Native families throughout time, are subsistence fishers: that’s their life; that’s what they do every day to feed their faces. Yet with Congress-approved funding, the State Department of Fish and Wildlife began plotting and executing seasonal raids on Nisqually fishermen when the salmon were running (34); many of these raids have been documented and are “ugly, heartrending brawls” (38). Images of women fishers being dragged out of canoes by the nets they’re holding onto for dear life; images of folks being tear gassed and arrested all appear in Carol Burns’ documentary which is gripping, moving (Burns).

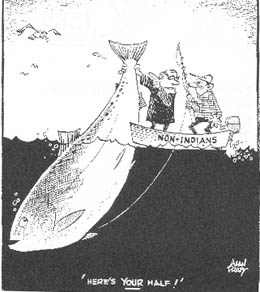

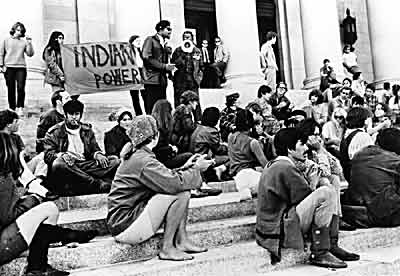

Adding to irony, Billy Frank Sr. and “other Nisqually fishermen had obtained a federal court injunction against state interference with their fishing, back in 1937”… “they had faith that the federal judiciary would honor the treaties” (40). In any case, the attention already drawn to Frank’s Landing during the 1960’s kicked off even more with the presence of actor Marlon Brando, “Canadian Native folk singer Buffy Saint Marie”, historian Richard White, future Oregon Congresswoman Elizabeth Furse, and black comedian Dick Gregory all lending their celebrity to the cause (Wilkinson 40; Burns; Ryan). Hank Adams, activist and member of the National Indian Youth Council, joined the fishing rights fight and garnered media attention from CBS’s Charles Kuralt, for example, by organizing a 2,000 person demonstration on the steps of Olympia’s capital building in 1964; Adams also raised funds for a report done by the American Friends Service Commission in 1967 named An Uncommon Controversy (Wilkinson 44; Burns). In 1968 Billy Frank Jr. demonstrated in Olympia’s Budd Inlet the inefficiency of outlawed gill net fishing yet was still arrested (Wilkinson 38; Burns). A few years later a major event that got national media attention was the violent arrests all of the 62 occupants at the encampment along the Puyallup River in 1970 by 300 police officers (Wilkinson 37; Burns).

Efforts for Natives to enforce Stevens’ treaties “meant establishing three fundamental points: tribal fishers could fish free of state regulation; tribes, as sovereign governments, had primary regulatory authority on reservation and at off-reservation sites; and the tribes had the right to harvest a substantial part of the runs” (Wilkinson 49). This brings us to the Sohappy v. Smith case in which decorated army veteran Richard Sohappy and his nephew David were arrested in 1968 for using gillnets in Oregon. This presented an opportunity to try a fishing rights case in federal court, so aforementioned Hank Adams conjured up funding for the litigation from the NAACP, and the case was filed in Portland’s United States District Court by Professor Ralph Johnson “on behalf of the Sohappys and twelve other Yakama tribal members” (49).

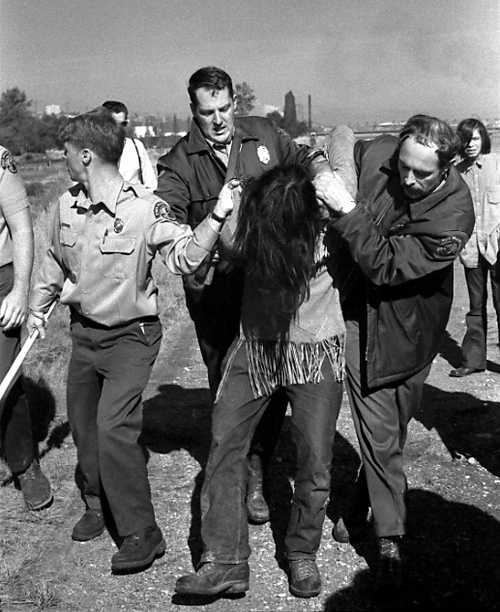

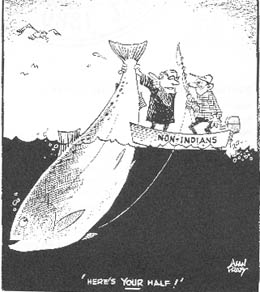

The case was assigned to Judge Robert C. Belloni who, in 1969, ruled in favor of the tribes who have federally granted “rights, outside of state law. Judge Belloni also ruled that the tribes had the right to an allocation of fish”… “‘a fair share’ of harvestable salmon” (50). Yet, what constitutes a “fair share”? To some the 1970 filing of United States v. Washington assigned to Judge George H. Boldt who, in 1974, ultimately and famously, ruled for a 50-50 allocation of harvestable salmon between treaty and non-treaty fishermen, was logical and ecologically conservative given that Natives, being about 1 percent of the population were taking about 5 percent of the harvestable fish (56). Judge Boldts’ ruling is furthered by acknowledging tribes’ own sovereign governmental powers outside of state regulation; tribes must roster their members and provide them with an identity card compensatory of off-reservation fishing; tribes are to follow regulations for salmon conservation. Out of this fishing war came the establishment of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, a confederation of Puget Sound and Olympia Peninsula tribes with Billy Frank Jr. as chairman since 1977 and each of the treaty tribes establishing their own natural resource departments.

It seems that the fishing wars were won; cedar and the salmon people got their recognition for being long-standing fishers. Long gone are the Medicine Creek days, but the effects have been long lasting and violent at times. Furthermore, there is still a battle out there and it is the status of salmonoids becoming endangered species. Long gone is the time when Natives fished outside of the context of the existence of the United States and perhaps fast approaching is the time when even the best fisheries commissions, hatcheries, and pollution control won’t be able to stop salmon populations from dwindling. “What good is the right to a share of the fish if there are no more salmon in the rivers? What good is the state’s right to regulate if it threatens a way of life that has existed since time immemorial” (Landau 63)?

Works Cited:

Anderson, Ross. “River Watch: Divided Interests Make A Deal”. Seattle Times/ Seattle Post Intelligencer. 17th May, 1987.

American Friends Service Committee: An Uncommon Controversy: an inquiry into the treaty-protected fishing rights of the Muckletshoot, Puyallup, and Nisqually tribes of Puget Sound. National Congress of American Indians. (1967).

Bates, Dawn; Hess, Thom; Hilbert, Vi. Lushootseed Dictionary. (1994). University of Washington Press Seattle and London.

Burns, Carol. “As Long as the Rivers Run”. Film on CD-ROM. Produced by Survival of American Indians Association 1968-1970.

Cone, Joseph and Ridlington, Sandy. The Northwest Salmon Crisis: A Documented History. (1996). Oregon State University Press Corvallis, Oregon.

Eckrom, J. A. Remembered Drums: A History of the Puget Sound Indian War. (1989).

Pioneer Press Books Walla Walla, Washington.

“Evan’s Aide Blames Police for Raid” Tacoma News Tribune 17 Feburary 1971.

Good Striker, Duane; Weaver, Jace. “TEK Wars: First Nations Struggle For Environmental Planning” Defending Mother Earth. (1996). Orbis Books Maryknoll, New York.

Hannula, Dan. “Blood Flows in Indian River Fight”. Tacoma News Tribune. 14, October 1965.

Hilbert, Vi. Haboo: Native American Stories from the Puget Sound. (1988). University of Washington Press Seattle, and London.

Landau, Jack L. “Empty Victories: Indian Treaty Fishing Rights in the Pacific Northwest.” Native Americans and the Law: Recent Legal Issues for American Indians, 1968 to the Present. (1996): 68-106. Garland Publishing, Inc. New York & London.

Lane, Bob. “Nets Confiscated Along Nisqually”. Tacoma News Tribune. 28 December 1971.

Mayne, Jack. “Treaties on Indian Fishing Rights Bolstered by U.S. Court Decision”. Seattle Post Intelligencer 4 March 1974.

MacNey, M. “Mixed Reactions Greet Fishing Suit”. Tacoma News Tribune. 19 Sept. 1970.

Morisset, Mason D. Pacific Northwest Indian Treaty Fishing Rights: A Survey of Recent Developments. Pirtle, Morisset, Schlosser & Ayer Seattle, Washington (1994).

Ryan, Jack. “Marlon Steals Lead In Mutiny on the River” Tacoma News Tribune. 2 March 1964.

Schwantes, Carlos Arnaldo. The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretative History. (1996). University of Nebraska Press.

Stewart, Hilary. Cedar. (1995). University of Washington Press.

Stewart, Hilary. Indian Fishing: Early Methods on the Northwest Coast. (1977).University of Washington Press.

Wilkinson, Charles. A Message From Frank’s Landing: A Story of Salmon, Treaties, and the Indian Way. (2000). University of Washington Press Seattle & London.

Wilkinson, Charles. Blood Struggle: the Rise of Modern American Nations. (2005): 157-173; 198-205. WW Norton & Company New York and London.

http://www.nwifc.org. Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission website; continually updated by various authors. (2010).

http://www.tolerance.org/activity/against-current. (2010).

Bob Satiacum (Puyuallup fishing rights activist) on right and actor Marlon Brando on the left.

Image from http://www.historylink.org/db_images/DWW226.JPG

Puget Sound Native Fishing rights demonstration at the capitol building in Olympia http://news.theolympian.com/150th/96249-32411.jpg

Political cartoon poking fun at the Boldt Decision of 1974 from http://www.historylink.org/db_images/Toon153.JPG

Demonstraters and police at intertribal encampment on Puyallup River September1970

http://www.stephenlehmer.com/puy_fish/Puy_fish_images/Puy1im_fw.jpg

http://www.stephenlehmer.com/puy_fish/Puy_fish_images/Puy1im_fw.jpg