Casey Kirpes

History

in Painting: Jacob Lawrence

“If at times my productions do not express the conventionally beautiful, there is always an effort to express the universal beauty of man’s continuous struggle to lift his social position and to add dimension to his spiritual being.” (Wheat, 47).

African Americans had many hardships to deal with during the American Revolution. When people came to America to build their lives, the Europeans brought Africans here by force to create a better economy for themselves. Through the progression of the American economy the minorities started to feel that they needed to be treated like equals in the “land of the free.” Jacob Lawrence was of African descent and he too believed in equal civil rights for all. He became interested in art and delivered his messages through paintings that he created throughout the twentieth century. Lawrence was a painter, drawing and mural artist. He created his works throughout a time in America when it was hard for the black man to come up ahead. He went through the depression and the end of the American progressive era; he also witnessed the great migration of African Americans traveling north, the Jazz Age and the Harlem renaissance. He also created many of his works relating to the Civil Rights movements and focused on great leaders such as Harriet Tubman, John Brown and Frederick Douglas. Jacob Lawrence was a witness to so much of American reconstruction and his artwork is rich with ideas that he had a first hand insight on. He sets a style all of his own by using real life images in an abstract way; he uses brilliant colors and creative detail in his paintings. There is a lot of movement in his work with the change of the decades and his messages are clear.

Jacob was born in New Jersey in 1917. He lived with his parents until they separated

in 1924, then ended up in foster care. He was eventually moved to Harlem where

it was hard for African Americans to attend any regular art schools. His early

interest in artwork led him to be one of the first black artists to be trained

by the African-American community in Harlem. After public school Lawrence attended

a daycare called Utopia Children’s House, where he met his first art instructor

Charles Alston, who taught him about non representational drawings. Alston wanted

Lawrence to use his own artistic ideas by making personal decisions about composition

and space; this would allow him to create a style of his own. Lawrence continued

throughout high school taking art classed from Charles Alston at the Harlem

Art Workshop. This art house for African Americans also became a forum for their

exhibitions, social, cultural and political events, which was very important

for this community at the time. As Lawrence’s artwork progressed he developed

his visual relationships and certain shapes he liked to use. Regarding his artwork

Jacob explains, “Our homes were very decorative, full of pattern, like

inexpensive throw rugs, all around the house. It must have had some influence,

all this color and everything. Because we were so poor the people used this

as a means of brightening their life. I used to do bright patterns after these

throw rugs; I got ideas from them, the arabesques, the movement and so on.”

(Hammond,27).

During his teen years, Lawrence visited many art museums on a regular basis

and became very interested in African American art and abstraction. He was very

inspired by the Harlem community where he grew up and did many of his works

based on the people and the community. He always used bold, bright colors and

elemental shapes. “This is Harlem” was one of his paintings done

to represent the black community where he grew up. The colors and shapes are

very brilliant and the painting is very busy. You can almost see it moving.

Lawrence was growing up in the 1930’s during the depression, he says “

the depression was actually a wonderful period in Harlem although we didn’t

know this at the time. Of course it wasn’t wonderful for our parents.

For them, it was a struggle, but for the younger people coming along like myself,

there was a real vitality in the community” (Hammond,49). His works during

this time revealed a lot of the poverty, crime, racial tensions, and police

brutality in Harlem at the time. Lawrence attended college on a scholarship

during 1937-1939. He attended the American Artists School in New York. He received

recognition for his paintings of Harlem at a solo exhibition in the Harlem YMCA.

Immigration is when you go from one’s native land to another country in

order to settle there permanently. Migration is when you go from one country,

region or place to settle in another. During the civil rights movements there

was a lot of migration going on in America. African Americans from the south

were moving into the north in hopes of gaining more equal civil rights. Harlem,

New York was one of the main destinations for many of these people and Harlem

housed over a quarter million African Americans. Between 1890 and 1910 the populations

doubled in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Illinois and tripled in New York (Turner,55).

The NAACP and the Urban League associations argue that during the migration

period that socioeconomic integration of black communities are perceived as

normal and not tainted by the massive gathering of black folks (Turner,55).

Another intriguing factor is that during 1920-1930 118,000 white people left

the Harlem area, yet 80 percent of businesses were still owned by whites. James

W. Johnson is quoted saying, “Negro Harlem is situated in the heart of

Manhattan and covers one of the most beautiful and healthful sites in the whole

city. It is not a fringe, it is not a slum, nor is it a ‘quarter’

consisting of dilapidated tenements.” (Turner,62)

African Americans really had to show the white American culture that they could live peacefully together and integrated together. Lawrence was a witness to the innovative and improvised lifestyles created by this migration. Lawrence states, “I was part of the migration, as was my family: my mother, my sister, and my brother…I grew up hearing tales about people ‘coming up,’ another family arriving. People who’d been in the north for a few years, they would say another family ‘came up’ and they would help them to get established…by giving them clothes and fuel and things of that sort…I was only about 10,11 or 12. It was the 20’s…And of course there was a great deal of tension throughout the country-the ethnic tension and so on-I guess you have a similar situation today.” Lawrence goes on to say, “But this was all new to me. I was a youngster and I heard these stories over and over again…I didn’t realize what was happening until about the middle of the 1930’s, and that’s when the Migration series began to take form in my mind” (Turner,64).

The people migrating north weren’t accustomed to the high speed close

knit urban communities as they were of the more rural areas. During 1940 and

1941 Lawrence created 60 paintings called “The Migration of the Negro.”

It was first exhibited at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery and traveled

for two years on display at other galleries across the nation, including white

owned. Lawrence’s artwork was now being accepted within the white community

and he found it hard to play two different roles because of his experiences

with being an African American (Sims,33).

Lawrence

recalls, “the endlessly fascinating patterns of cast-iron fire escapes

and their shadows created across the brick walls. The variegated colors and

shapes of pieces of laundry on lines stretched across the back yards…

the patterns of letters on the huge billboards and the electric signs”

(Sims,45). In his artwork Lawrence always showed the black community’s

role in society and his developments into a man and an artist. He painted what

he saw as well as what he heard. With the Jazz age he tried to incorporate the

tunes that he heard with the strokes of his paintbrush. During 1942 and 1943

he created 30 paintings of his Harlem experiences including, black working women,

leisure time, health concerns and roles religion played in their lives.

Lawrence

recalls, “the endlessly fascinating patterns of cast-iron fire escapes

and their shadows created across the brick walls. The variegated colors and

shapes of pieces of laundry on lines stretched across the back yards…

the patterns of letters on the huge billboards and the electric signs”

(Sims,45). In his artwork Lawrence always showed the black community’s

role in society and his developments into a man and an artist. He painted what

he saw as well as what he heard. With the Jazz age he tried to incorporate the

tunes that he heard with the strokes of his paintbrush. During 1942 and 1943

he created 30 paintings of his Harlem experiences including, black working women,

leisure time, health concerns and roles religion played in their lives.

Lawrence was drafted into the United States Coast Guard and served for four

years between 1942 and 1946. He started as a Stewards Mate in a segregated regiment

because he was African American, but was eventually promoted to Coast Guard

Artist, whose job was to document the war throughout Italy, England, Egypt and

India. There were 48 paintings he created during the war, which have been lost

so when he received special permission he was able to recreate his “War

Series” paintings. This series, which Lawrence completed during World

War II, includes 14 compositions. They were all completed in one-year’s

time between 1946 and 1947. These include titles such as; Prayer, Alert, How

Long?, and Victory. The paintings tell his story of war and how men felt during

times of war (Nesbett, 98).

Lawrence tells about the “War Series” by saying, “I tried

to capture the essence of war. To do this I attempted to portray the feelings

and emotions that are felt by the individual, both fighter and civilian.”

(Wheat, 74). He goes on to say, “A wife or a mother receiving a letter

from overseas, the next of kin receiving a notice of casualty. The futility

men feel when at sea or down in a foxhole just waiting, not knowing what part

they are playing in a much broader and gigantic plan.” (Wheat, 47). He

really captures these emotions in all of his work and his life experiences give

him the motivation to create such powerful and emotional work.

Because Lawrence had been witness to many elements, all which are influential

of his artwork, during the 1950s his works seemed to be created with larger

psychological depth (Sims). The way he used layers of patterns and shadows and

lighting express the depth of the works. Social protest was definitely a theme

he used throughout his artistic career and more so in the 1960s when he was

witnesses to the lunch counter sit-ins by African Americans and stories of the

Freedom Riders for civil rights.

Lawrence did document a lot of the civil rights movement through his work. His

“Harriet Tubman” series depicts a lot of the earlier fights against

slavery. He liked to document fascinating people whom he admired for standing

up for their civil rights. He stated in 1945, “The human subject is the

most important thing. My work is abstract in the sense of having been designed

and composed, but it is not abstract in the sense of having no human content…I

want to communicate. I want the ideas to strike right away.” (Wheat, 24).

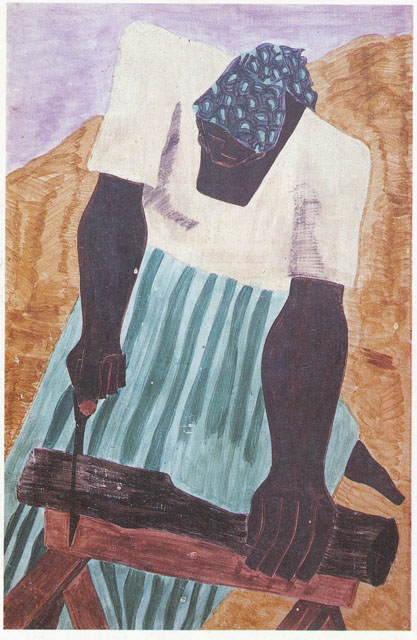

The Harriet Tubman series includes a painting of her as a water girl, one of

cotton pickers and water girls slaving away and another of a man who looks like

he is hanging by the sky from his wrists with his back turned towards the audience.

Below this last painting the caption reads, “I am no friend of slavery,

but I prefer the liberty of my own people to that of another people, and the

liberty of my own race to that of another race. The liberty of the descendants

of Africa in the United States is incompatible with the safety and liberty of

European descendants. Their slavery forms an exception to the general liberty

in the United States,” Henry Clay (Wheat, 57).

These paintings are very real and

you can see the pain in them with the darker background coloring and the strokes

of the brush. Tubman was born a slave and escaped to her freedom while helping

others to do the same. Lawrence proclaimed, “This is one of the great

American sagas…Exploring the American experience is a beautiful thing…the

building of America, the contributions all of us have made, which is part of

the experience. The Negro woman has never been included in American History.”

(Wheat, 47).

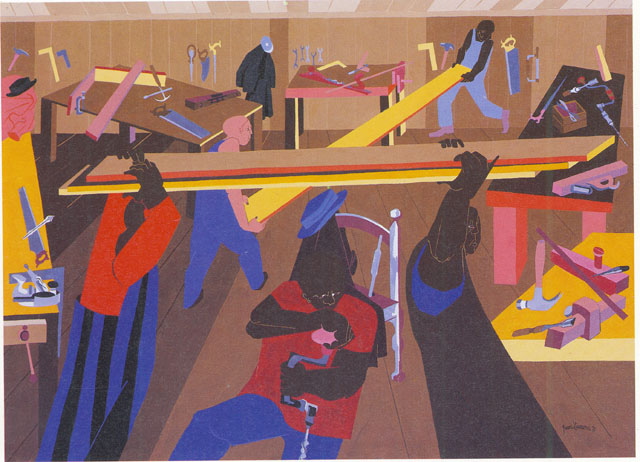

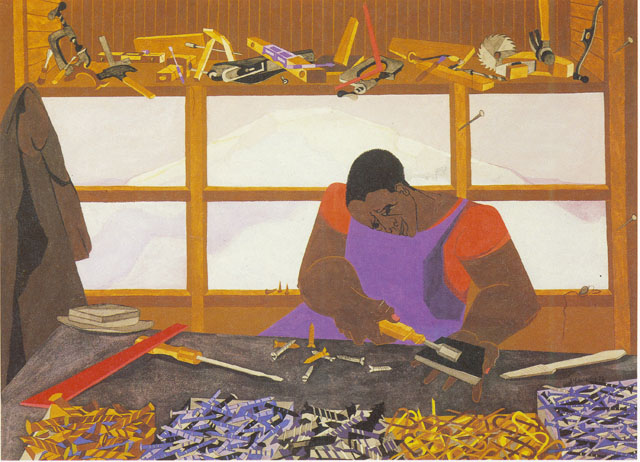

Lawrence moved west to begin teaching in California, he only stayed a few months until he was appointed the “Visiting Artist” at the University of Washington here in Seattle. Later he was accepted for a full time position teaching painting, drawing and design. He and his wife, also an artist, ended up settling permanently in Seattle. While in Washington he created a later series of paintings called “The Builders Series.” It was to focus on carpenters, cabinetmakers and men with jobs of the like.

Lawrence describes the builders as more of a theme, “The Builders came

from my own observations of the human condition. I like the symbolism, I think

of it as a man’s aspiration, as a constructive tool-man building.”

(Wheat, 143). In this series you see the brilliant colors and the detailed tools.

The way the men look so dedicated to the work they are doing. He uses new stylistic

features in these paintings by using Mt. Rainier as a background or presenting

it in a bird’s eye view. The larger objects are played off against the

smaller more detailed ones in the front of the composition and you see more

detail in the hands and faces of the subjects. He kept this style with other

work he composed for; an example is the Bumbershoot poster he was asked to create

for the Seattle music event held in 1976. You see the detail and the greenery

used in the background.

In Seattle Lawrence has received many awards and has been asked to create many

compositions relaying a certain person or theme. He was awarded the Spingarn

Medal in 1970, which is the highest honor award given by the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People. He has been asked to create posters for

many Seattle events, such as the Bumbershoot poster. The state of Washington

also asked Lawrence to create a small series on George Washington Bush, a black

explorer, to exhibit in the State Capital Building. The Whitney Museum of New

York asked him to compile a massive one-man exhibit, which traveled to five

US cities. His work has even been presented to the Pope at the Vatican, which

they decided to keep as part of the permanent collection displayed there.

His work has inspired and delighted many kinds of people and has told many stories

of growing up through the 20th century in America. Through the African American

Civil Rights movement to his first hand combat during World War II, Jacob Lawrence

has had many experiences and feelings to back up his brilliant artwork. He has

paved a way for others like himself by being one of the first artists of color

to be accepted into the white world of early America.

Works Cited

Johnson, Mark M., African American

Works on Paper. Artists Activities. Oct. 2003. Vol

134. Issue 2.

King-Hammond, Leslie, “Inside-Outside, Uptown-Downtown, Jacob Lawrence

and the

Aesthetic Ethos of the Harlem Working-class Community. Seattle University

Press. 2001.

Nesbett, Peter T., Jacob Lawrence: Paintings, drawings, and murals. University

of

Washington Press in association with Jacob Lawrence catalogue Raisonne’

Project. 2000.

Nesbett, Peter T., Jacob Lawrence, Thirty years of Prints. Seattle. Francine

Seders

Gallery in association with University of Washington Press. 1994.

Sims, Lowery Stokes, The Structure of Narrative, Form and Content in Jacob Lawrence’s

Builder Paintings, 1946-1998,” Seattle. University of Washington Press.

2001.

Turner, Elizabeth Hutton. Jacob Lawrence the Migration Series. Washington DC.

Rappahannock Press in association with the Phillips Collection. 1993.

Wheat, Ellen Harkins. Jacob Lawrence, American Painter. University of Washington

Press in association with the Seattle Art Museum. 1986.

www.whitney .org/jacoblawrence/art/migration.html

Pictures Cited

Title Page; Jacob Lawrence’s Self Portrait. Found at www.whitney

.org/jacoblawrence/art/migration.html.

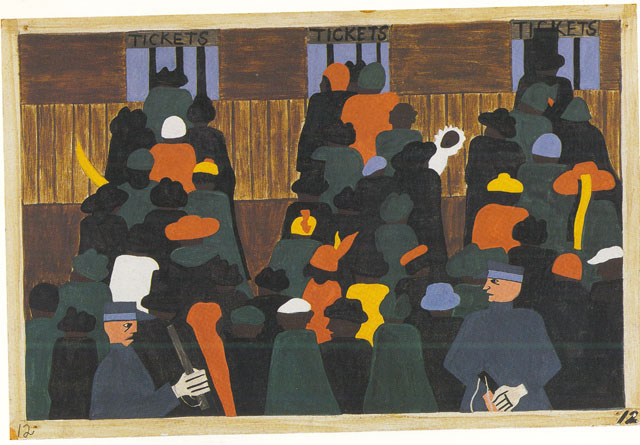

Picture One; “This is Harlem,” number one of Harlem series. Displayed

at Hishhorn

Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washigton, D.C. Found

from Ellen Harkins Wheat’s Jacob Lawrence, American Painter.

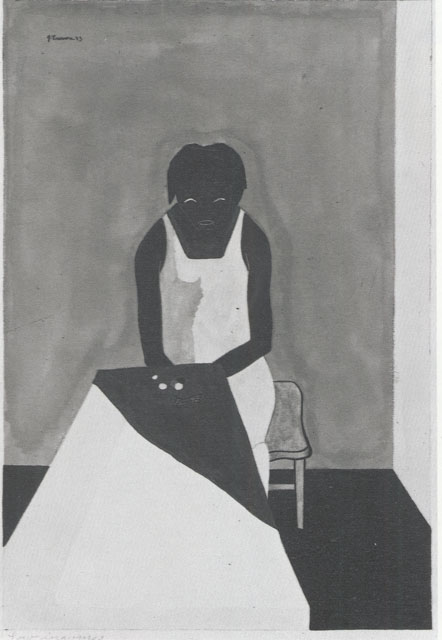

Picture Two; “Most of the people are very poor. Rent is high. Food is

high.” Number

two of the Harlem Series. Collection of Pietro Belluschi. Found from Ellen

Harkins Wheat’s Jacob Lawrence, American Painter.

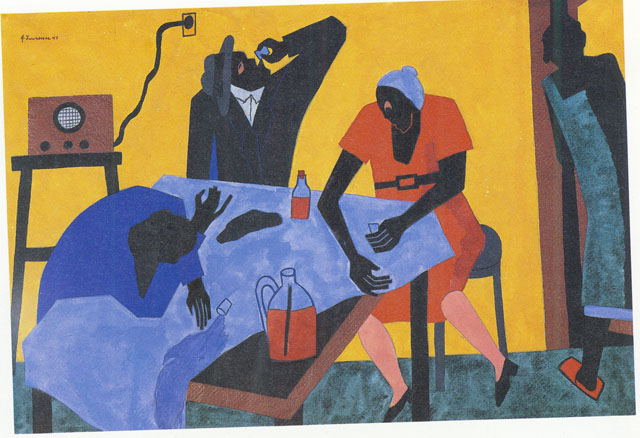

Picture Three; “You can buy bootleg whiskey for twenty-five cents a quart.”

Number 15

of the Harlem Series. Can be found at Portland Art Museum, Oregon. Found

from Ellen Harkins Wheat’s Jacob Lawrence, American Painter.

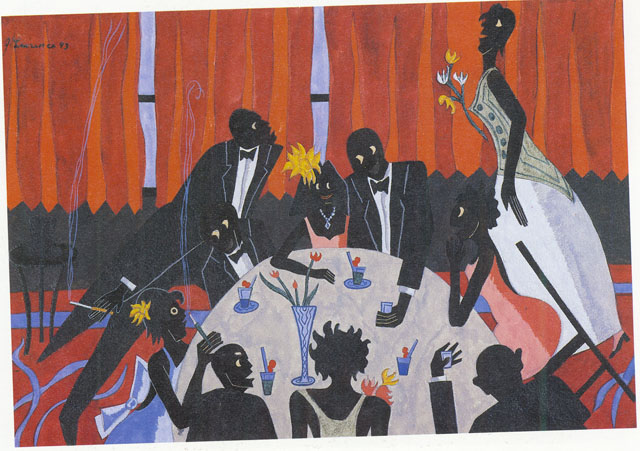

Picture Four; “And Harlem Society Looks On.” Number 19 of the Harlem

Series. Can be

found at Portland Art Museum, Oregon. Found from Ellen Harkins Wheat’s

Jacob Lawrence, American Painter.

Picture Five; “And the Migration Spread.” Number 23 of the Migration

Series. Can be

found in the Ohio State University Museum. Found in Peter Nesbett’s Jacob

Lawrence.

Picture Six; “The railroad stations were at times so over-packed with

people leaving that

special guards had to be called in to keep order.” Number 12 of the Migration

series. Found in Peter Nesbett’s Jacob Lawrence.

Picture Seven; “The railroad stations in the South were crowded with people

leaving for

the north.” Number 32 of the Migration Series. Can be seen at the UCLA

Art

Galleries, Dickson Art Center, Los Angeles, CA. Found in Peter Nesbett’s

Jacob

Lawrence.

Picture Eight; “Going Home.” Number 12 of the War Series. Can be

seen at the Whitney

Museum of American Art in New York. Found in Ellen Harkins Wheat’s Jacob

Lawrence, American Painter.

Picture Nine; “Shipping Out.” Number 2 of the War Series. Can be

seen at the Whitney

Museum of American Art in New York. Found in Ellen Harkins Wheat’s Jacob

Lawrence, American Painter.

Picture Ten; “Casualty- The Secretary of War Regrets.” Can be seen

at the Whitney

Museum of American Art in New York. Found in Ellen Harkins Wheat’s Jacob

Lawrence, American Painter.

Picture Eleven; “Subway, 1938.” Can be seen at Schomburg Center

for Research in

Black Culture Art and Artifacts Division, New York Public Library. Found at

www.whitney .org/jacoblawrence/art/migration.html

Picture Twelve; “Harriet Tubman worked as a water girl to cotton pickers;

she also

worked at plowing, carting and hauling logs.” Number 7 of the Harriet

Tubman

Series. Can be seen at Hampton University Museum in Virginia. Found in Ellen

Harkins Wheat’s Jacob Lawrence, American Painter.

Picture Thirteen; “I am no friend of slavery.” Number 2 of the Harriet

Tubman series.

Can be seen at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Found in

Ellen Harkins Wheat’s Jacob Lawrence, American Painter.

Picture Fourteen; “With sweat and toil and ignorance he consumes his life,

to pour the

earnings into channels from which he does not drink.” Number 1 of the

Harriet

Tubman Series. Can be seen at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New

York. Found in Ellen Harkins Wheat’s Jacob Lawrence, American Painter.

Picture Fifteen; “Builders number 1,1969.” Part of a private collection

found in Ellen

Harkins Wheat’s Jacob Lawrence, American Painter.

Picture Sixteen; “Builders number 1,1970.” Part of a private collection

found in Ellen

Harkins Wheat’s Jacob Lawrence, American Painter.

Picture Seventeen; “Bumbershoot ’76 Poster, 1976.” Collection

of Gwendolyn and

Jacob Lawrence. Found in Ellen Harkins Wheat’s Jacob Lawrence, American

Painter.