"Well, Lady, Here's One Woman You Don't Represent"

by Cassie Andreotti

You are walking down a city street and handed a small leaflet. Looking down, you see the profile of a middle aged woman, framed by a simple black dress, and white bonnet. She sits in a rocking chair, hands resting on her lap, eyes absently gazing out of the picture as if waiting for someone or something. The caption surrounding the picture reads: “WHICH GETS YOUR VOTE? MOTHER OR THE SALOON? VOTE DRY. Ask the first ten mothers you meet if they would vote for the saloon and govern yourself accordingly.” This is the roaring twenties; the Prohibition Movement is in full effect.

You are walking down a city street and handed a small leaflet. Looking down, you see the profile of a middle aged woman, framed by a simple black dress, and white bonnet. She sits in a rocking chair, hands resting on her lap, eyes absently gazing out of the picture as if waiting for someone or something. The caption surrounding the picture reads: “WHICH GETS YOUR VOTE? MOTHER OR THE SALOON? VOTE DRY. Ask the first ten mothers you meet if they would vote for the saloon and govern yourself accordingly.” This is the roaring twenties; the Prohibition Movement is in full effect.

The image of the stern mother, begging wife and neglected daughter were all common depictions strategically used during prohibition. According to David E. Kyvig in Women Against Prohibition, “American women (now fully enfranchised) could be counted upon for nearly unanimous support of prohibition.” Ironically the picture of a suited, strong, objective woman is also the image behind the repeal of the same amendment they had once advocated. Although overshadowed by their male counterparts, women played a substantial role in the collapse of Prohibition.

Going back to the late seventeenth century the prohibition of distilled liquor has been a relevant subject. Some might even say it is the oldest movement in American history. Prior to the Civil War churches, primarily Methodist and Protestant, strongly encouraged abstinence from the ‘demon rum.’ Not long after the war the first—all male—prohibition organization was formed, the Prohibition Party. Still in action today, they are considered the oldest “third party” in America, and continue to stand firmly against the commercial sale of alcohol, gambling, pornography, the ‘homosexual agenda,’ and abortion.

Going back to the late seventeenth century the prohibition of distilled liquor has been a relevant subject. Some might even say it is the oldest movement in American history. Prior to the Civil War churches, primarily Methodist and Protestant, strongly encouraged abstinence from the ‘demon rum.’ Not long after the war the first—all male—prohibition organization was formed, the Prohibition Party. Still in action today, they are considered the oldest “third party” in America, and continue to stand firmly against the commercial sale of alcohol, gambling, pornography, the ‘homosexual agenda,’ and abortion.

Another male-dominated organization better remembered for building the groundwork of the prohibition era was the Anti-Saloon League of America. Established in Ohio in 1893, the league as, Holland Webb in Temperance Movements and Prohibition wrote “soon took the driver seat of the prohibition cause.” By 1908 they had organized a League in every state except four, spreading their propaganda throughout the nation via the American Issue Publishing Co., which they conveniently happened to own. While men were in the limelight, utilizing prohibition for power and political platforms, Carrie Nation, Susan B. Anthony, and Francis Willard (to name a few) were diligently doing their part to organize the other half of the nation—women.

Even before the Anti-Saloon League appeared on the scene, women found the ‘demon rum’ responsible for high crime rates, prostitution and intoxicating children. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union was organized in Ohio in 1874, twenty years before the League. The WCTU developed from what began as the ‘Women’s Crusade.’ During the Crusade, women would roam the streets, praying in front of saloons and singing hymns, in hope that the saloon owners would shut their doors. Some protesters were attacked by bar owners dogs or had beer dumped on their bowed heads. Despite threats and harassment, the women’s attempts to close saloons worked, and many people signed pledges (i.e. Lincoln—Lee Legion) assuring they would refrain from drinking.

By 1892 the WCTU had 150,000 members; mind you, this was an entire year before the Anti-Saloon League had been activated. The group was headed by Frances Willard, a young, middle class, devoutly religious woman who, after traveling overseas, decided to give her life to the prohibition of alcohol. As stated in Temperance Movement and Prohibition, she declared, “I believe that in this simple change of personal attitude, from passive to aggressive, lies the only force that can free this land from the drink habit and the liquor traffic.” Willard also helped create the National Temperance Hospital which she said “demonstrate[d] that practical and successful treatment of diseases was possible without the use of alcohol.” Although many peaceful reformers were associated with the WCTU, some were determined the peaceful approach was not getting results.

The ‘aggressive’ switch Willard describes can be seen in the actions of an infamous WCTU member, Carrie Nation. Nation, pictured below with hatchet in hand, was a large woman, standing six feet tall and weighing 175 pounds. I suppose it was only logical she chose violent tactics as opposed to the passive prayer and songs of sobriety. She was well known for “leveling saloons” throughout Kansas with rocks, rods and broken bottles avenging the death of her drunkard husband.  Although jailed on numerous occasions, Nation was always released, as the saloons she was demolishing were, in fact, illegal. Ironically, her antics produced the reverse effect. Several bar owners wrote to Nation, inviting her to break up their saloons because it was actually good for business. Also at this time, literature was taking on the topic of temperance.

Although jailed on numerous occasions, Nation was always released, as the saloons she was demolishing were, in fact, illegal. Ironically, her antics produced the reverse effect. Several bar owners wrote to Nation, inviting her to break up their saloons because it was actually good for business. Also at this time, literature was taking on the topic of temperance.

Female authors wrote stories of women and children who were the victims of alcohol, primarily from a drunken husband or father. Titles such as Bessie’s Mother, Poor Bennie, and The Sick Girl, inspired Willard and Nation. Temperance poetry and songs also became popular methods of protest and were used as women crusaders marched past saloons. One famous hymn sung by Nation goes as follows:

Who hath sorrow? Who hath woe?

They dare not answer no?

They whose feet to sin incline,

While they tarry at the wine.

There were other notable singing temperance groups, one was the Hutchinson Family. Made up of thirteen children, they traveled the country singing “Lament of the Widowed Inebriate,” and “Drink Nothing Boys, but Water.” Films also became a medium for the prohibition position, but many members of the WCTU refused to go theaters as they were seen as immoral.

Another female prohibitionist of the time was Susan B. Anthony. For over a century women had been fighting for equal rights, specifically the opportunity to have their voices heard in the political arena. Susan B. Anthony, an advocate of prohibition and the Women’s Liberation Movement, agreed that women would certainly be in favor of Prohibition but could do nothing without the vote. Attempts were made to join the Prohibition Party with the hope of gaining a greater majority of support for both planks. Unfortunately, at the time the Party opposed women’s suffrage and turned their backs on, what could have been, one of their greatest allies. However, the Anti-Saloon League took notice of the importance of women voters and did in fact support their right to go to the polls. By 1920, the nineteenth amendment had been passed, creating a voice for women who in turn made up 60.7 per cent of the voters for prohibition. Ironically, some of the same women whom helped promote prohibition would eventually be participants of its demise.

Women, in the 1920’s, were beginning to play significant roles in social and political reform. As noted by Betty Friedan in the Feminine Mystique, “The feminists had only one model, one image, one vision, of a full and free human being: man.” The first voices to speak out for women’s rights in America were that of Fanny Wright, and Ernestine Rose. They were not received with open arms and as Friedan said, were referred to as “woman a thousand times below a prostitute” and the “red harlot of infidelity.” To be a feminist was to violate the “God-given nature of woman.” Ladies were to keep quiet and do as they were told by their husbands. Just as whites feared Black Supremacy during the Civil Rights Movement, men now feared women would “destroy the home and make slaves of [them].”

Thus, the thought of women voting frightened some men. Friedan describes how they saw them as “unsusceptible to bribery, more militant and bent on disturbing reforms.” As women began to speak out for fair employment, and equal wages, they also wanted to partake in a cold beer at the end of the day with their male colleagues. After all shouldn’t they be able to enjoy the fruits of their labor with a cocktail? However, saloons were considered ‘male institutions’ as Mary Jane Lupton wrote in Ladies’ Entrance: Women and Bars, “it was not simply a place where men went, but part of the system of privileges and freedoms which men enjoyed and which women did not.” Women, if they were allowed, had to use a side door and sit by themselves in another part of the saloon. Drinking was not only a matter of equality but was also a matter of culture and class.

Alcohol was not merely a means for getting drunk, but was a heritage brought from overseas by immigrants who migrated to the U.S. According to Friedan, “drunkenness was an issue among Catholic women, [but] total abstinence was out of the question in a culture where wine and beer watered the cycle of life from christenings, and weddings to funerals.” Not only were immigrants and Catholics “intemperate,” but the middle class American woman were fond of Lydia Pinkhams’s Vegetable Compound, a medicine containing 21 per cent alcohol, to get rid of their headaches. In fact, France Willard, President of the WCTU, admitted to drinking while abroad, after a physician from Copenhagen recommended wine instead of water! Some women even set up breweries in their kitchens as a means of income. It is no wonder then that a women’s coalition against prohibition would soon emerge on the scene.

The eighteenth amendment had been ratified after a connection was made between ‘saloons life,’ prostitution, gambling and alcoholism. But as the twenties progressed under the outlawing of booze, crime rates soared instead of dropped, speakeasies replaced saloons and children were more susceptible to drinking. Women started to take notice of the downward trends perpetuated by prohibition.

The eighteenth amendment had been ratified after a connection was made between ‘saloons life,’ prostitution, gambling and alcoholism. But as the twenties progressed under the outlawing of booze, crime rates soared instead of dropped, speakeasies replaced saloons and children were more susceptible to drinking. Women started to take notice of the downward trends perpetuated by prohibition.

Regrettably, women’s names are not the first, or the second for that matter, to appear when one researches the anti-prohibition movement. Iconic men such as John D. Rockelfeller and Alfred P. Sloan (president of General Motors) are mentioned as lead advocates against the prohibition of alcohol. Their letters discussing the failure of prohibition to the President appear to be the catalysts for the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment, along with such male-dominated organizations as the Moderation League of New York, the Constitutional Liberty League of Massachusetts, and the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment. Charles Sabin, treasurer and member of the AAPA is another predominant figure whom advocated the repeal of prohibition. However, his wife, referred to as Mrs. Charles H. Sabin in articles such as the Movement Against Prohibition, is rarely given credit.

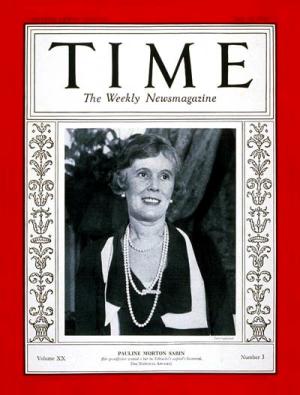

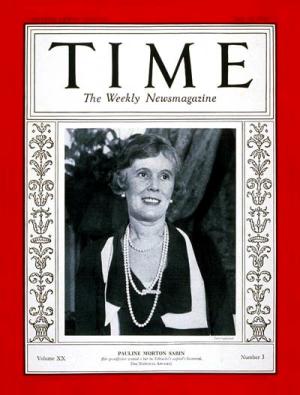

Pauline Morton Sabin, founder of the Women’s National Republican Club and member of the Suffolk County Republican Committee, began her political career siding with prohibitionists. She felt, as a mother, a world without liquor would be beneficial for her sons. As many mothers, she explained, “had believed that prohibition would eliminate the temptation of drinking from their children’s lives.” Unfortunately, prohibition had the reverse effect on children and politics. Sabin witnessed the hypocrisy firsthand of her fellow politicians supporting more sever prohibition laws, and later that same day sipping a cocktail.

In 1929, Sabin coordinated what would be known as the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR). Her decision to do so stemmed from a claim made by, then WCTU president Ella Boole, when she said “I represent the women of America!” Sabin thought to herself, “Well, lady, here’s one woman you don’t represent.” The WONPR held their first meeting at the Drake Hotel in Chicago and was attended by twenty-four women from eleven states. The conference drew national attention boosting the membership to 100,000, and in two years claimed one million members, more than any other anti-prohibition organization.

The WONPR’s influence not only came from the upper-class, white women who began the group, but the housewives, working-class and foreign-born women who joined because of their shared maternal concern. During the 1920s there were distinct barriers between race and gender. Many bourgeois, white, ladies associated with women’s liberation did not believe the poor, black, working-class women had much of an opinion on social and political movements. However as David Kyvig explains in Women Against Prohibition, “[a] noticeably higher percentage of WONPR members were working women…” This acceptance  of women of all classes considerably helped the WONPR increase their numbers and thus their voting power.

of women of all classes considerably helped the WONPR increase their numbers and thus their voting power.

In 1932 Time Magazine wrote an article about Sabin and the other women of the WONPR. The ladies had met to discuss the vote for presidential candidate as their platforms had changed; the Republican, Hoover, now advocated prohibition and the Democrat, Roosevelt, did not. Although Sabin and other members of the WONPR were firm Republicans, they were also adamant about the repeal of the eighteenth amendment and sided with the Democratic Party. Approximately sixty-four members of the WONPR resigned due to the swing from Republican to Democrat. This, mind you, is only a mere fraction of the one million members nationwide.

Opponents of the women’s group often stated the WONPR was nothing more than the AAPA’s puppets, or as Kyvig wrote, “a clever advertising devise.” Nothing could be further from the truth. Members of the WONPR so far exceeded those of their male counterparts it was incredible to say that the women were not acting of their own freewill. This can be seen by Sabin’s republican affiliation, although married to a prominent democrat, and then her disapproval and departure of Hoover, whom she had strongly supported prior to his dry announcement. Another attribute that separated the women’s organizations from the men’s was their proposed solutions for the repeal of the eighteenth amendment.

Although agreeing with the AAPA’s arguments and studies, the WONPR went beyond the men’s organization and suggested political strategies to solve the alcohol dilemma. As written in the Times magazine the organization was willing to:

- assist in framing temperate state liquor laws

- insist that national prohibition remain effective until such laws are operative

- conduct a campaign of temperance education throughout the nation’s schools, churches, and welfare.

With certain ground rules and a foundation to stand upon, the WONPR was not just fighting against the eighteenth amendment because others were, or because they wanted the right to drink, but because they knew prohibition had not worked. It had always been assumed that women were dry and would cast their vote for prohibition. But as time went by and the country outlawed booze, crime rates soared instead of dropped, speakeasies replaced saloons and children were more susceptible to drinking.

While the article written in Time states, women were given “[f]ull credit for helping to bring about national Prohibition,” where is it written that women were given any credit for its repeal? The women of the anti-prohibition movement deserve some recognition. They were brave enough to step out of their traditional role of religious Crusader and silent servant of the household in order to voice their political agenda to the public. So remember this when you unconsciously drive to the local liquor store or visit your regular watering hole; it was women who helped make it possible for you to kick back, relax and crack open a cold one.

Notes

Burt, Elizabeth. “Conflicts of Interest.” Journalism History. Vol. 26 (2000): p94-107

Currier, Nathaniel. The Drunkards Progress. From the First Glass to the Grave. 1846. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Image p2

Rice, Stuart A. “Prohibition and Statistics.” The Journal of Social Forces. Vol. 2 (Nov. 1924): p654-657

We Want Beer 1933. 28 Oct. 1932. Newark, NJ. Image p7

Anti-Saloon League. Which Gets Your Vote. 1920s westervillelibrary.org. 1 Dec 2010.

Kyvig, David E. “Women Against Prohibition.” American Quarterly. Vol. 28 (1976): p465-482. Print.

“Values of the Prohibition Party.” prohibition.org. n.d. Web. Jan. 15 2011

Holland, Webb. “Temperance Movement and Prohibition.” International Social Science Review. Vol. 74 (1999): p61-69. Print.

Davidson, Nichols and. Carry A. Nation. 1901. Kansas Museum of History.

Gebhart, John C. “Movement Against Prohibition.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Vol. 163 (1932): p172-180. Print

Friedan, Betty. Feminine Mystique. New York, NY: Norton and Company Ltd., 2001. Print.

Lupton, Mary Jane. “Ladies’ Entrance: Women and Bars.” Feminist Studies. Vol. 5 (1979): p571-586

“Prohibition: Ladies at Roslyn.” Time 18 June 1932. Online.

You are walking down a city street and handed a small leaflet. Looking down, you see the profile of a middle aged woman, framed by a simple black dress, and white bonnet. She sits in a rocking chair, hands resting on her lap, eyes absently gazing out of the picture as if waiting for someone or something. The caption surrounding the picture reads: “WHICH GETS YOUR VOTE? MOTHER OR THE SALOON? VOTE DRY. Ask the first ten mothers you meet if they would vote for the saloon and govern yourself accordingly.” This is the roaring twenties; the Prohibition Movement is in full effect.

You are walking down a city street and handed a small leaflet. Looking down, you see the profile of a middle aged woman, framed by a simple black dress, and white bonnet. She sits in a rocking chair, hands resting on her lap, eyes absently gazing out of the picture as if waiting for someone or something. The caption surrounding the picture reads: “WHICH GETS YOUR VOTE? MOTHER OR THE SALOON? VOTE DRY. Ask the first ten mothers you meet if they would vote for the saloon and govern yourself accordingly.” This is the roaring twenties; the Prohibition Movement is in full effect.  Going back to the late seventeenth century the prohibition of distilled liquor has been a relevant subject. Some might even say it is the oldest movement in American history. Prior to the Civil War churches, primarily Methodist and Protestant, strongly encouraged abstinence from the ‘demon rum.’ Not long after the war the first—all male—prohibition organization was formed, the Prohibition Party. Still in action today, they are considered the oldest “third party” in America, and continue to stand firmly against the commercial sale of alcohol, gambling, pornography, the ‘homosexual agenda,’ and abortion.

Going back to the late seventeenth century the prohibition of distilled liquor has been a relevant subject. Some might even say it is the oldest movement in American history. Prior to the Civil War churches, primarily Methodist and Protestant, strongly encouraged abstinence from the ‘demon rum.’ Not long after the war the first—all male—prohibition organization was formed, the Prohibition Party. Still in action today, they are considered the oldest “third party” in America, and continue to stand firmly against the commercial sale of alcohol, gambling, pornography, the ‘homosexual agenda,’ and abortion. Although jailed on numerous occasions, Nation was always released, as the saloons she was demolishing were, in fact, illegal. Ironically, her antics produced the reverse effect. Several bar owners wrote to Nation, inviting her to break up their saloons because it was actually good for business. Also at this time, literature was taking on the topic of temperance.

Although jailed on numerous occasions, Nation was always released, as the saloons she was demolishing were, in fact, illegal. Ironically, her antics produced the reverse effect. Several bar owners wrote to Nation, inviting her to break up their saloons because it was actually good for business. Also at this time, literature was taking on the topic of temperance. The eighteenth amendment had been ratified after a connection was made between ‘saloons life,’ prostitution, gambling and alcoholism. But as the twenties progressed under the outlawing of booze, crime rates soared instead of dropped, speakeasies replaced saloons and children were more susceptible to drinking. Women started to take notice of the downward trends perpetuated by prohibition.

The eighteenth amendment had been ratified after a connection was made between ‘saloons life,’ prostitution, gambling and alcoholism. But as the twenties progressed under the outlawing of booze, crime rates soared instead of dropped, speakeasies replaced saloons and children were more susceptible to drinking. Women started to take notice of the downward trends perpetuated by prohibition.  of women of all classes considerably helped the WONPR increase their numbers and thus their voting power.

of women of all classes considerably helped the WONPR increase their numbers and thus their voting power.