1

1The Organized Persistence of A. Philip Randolph: A Blueprint for Positive Social Change

by Chris Carter

Civil rights for African-Americans did not magically appear one day while racists weren’t looking- African-Americans suffered for them in unimaginable ways. No one gave blacks permission to vote or to have equality in the workforce. No one gave African-Americans the right to equal education or to go freely into any establishment. African-Americans did not wake up one day able to sit anywhere they wanted to on the bus or able to live in area they chose of a city or to even use any bathroom they chose. There is a false notion among many people that the civil rights movement was comprised of a few marches that happened in the sixties and the death of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In their view, just a few notorious events resulted in equality for African Americans. This is a dangerous notion for the simple fact that, if the blueprints for positive social change are lost, what recourse can there be to injustices by those in power?

The foundation of the civil rights movement was laid in the beginning of the twentieth century and still goes on today. One man who represented and led a great deal of that foundational part was A Phillip Randolph. His work as a civil rights leader and labor organizer spanned seven decades and helped change the course of American history.

1

1

With determination and planning, Randolph was able to develop particularly effective blueprints for social change. An understanding of his determined attitude can be seen when, prior to the United States’ entrance into WWII, he met with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt- who had offered to call up war industry leaders and tell them to hire blacks. “We want you to do more than that, we want something concrete something tangible, definite, positive and affirmative.“ When asked what he meant, Randolph presented his radical proposal: “Mr. President we want you to issue an executive order making it mandatory that negroes be permitted to work in these plants.”2 Though Randolph is credited with forcing Roosevelt’s hand equal importance must be placed on what he did to help create these changes so that his steps, alongside other African-American civil rights leaders, might be figuratively retraced to create future social change.

The first step in every plan that Mr. Randolph executed was to point out social problems and inform people about the possibility of change. He co-founded a radical magazine in 1917 called The Messenger with Chandler Owen. This magazine was not only an anti Jim Crow and anti lynching magazine it also spoke against Marcus Garvey, who wanted Blacks to go back to Africa . The Messenger, which was edited by Randolph, denounced this idea as farfetched and exposed Garvey and his ideas as unpractical while also accusing him of taking energy and resources from the movement for practical change in America. Randolph spoke sarcastically of Garvey’s supposed achievements in and essay Reply to Marcus Garvey ; “See what I have done; see what we have got! Down with the traitors and agitators who point out my faults! Down with all the negro leaders but me! Hurrah! For the Klu Klux Klan! Up with Kleagle Clark! Up with Marcus Garvey!” Will be the effusive ejaculation of this black Don Quixote.” 3

While the magazine editorialized against to the United States entering WWI, Randolph also used the magazine as a platform to speak out against blacks fighting in World War I. After all, what was there to gain for an African-American to defend democracy that was not their own? What The Messenger spoke for was that which could be accomplished: African-American equality in the work force and “a way up and out.” The magazine also took a solid stand on social issues like segregation. The F.B.I took Randolph in for questioning, mainly because of his ties to the Socialist party, but also because he was anti war and spoke against African-Americans fighting in the Great War. In another of his essays The Negro in Politics Randolph thoroughly explained his support of the Socialist Party:

“I maintain that since the Socialist Party is supported financially by working men and women, and since its platform is a demand for the abolition of this class struggle between the employer and the worker, by taking over and democratically managing the sources and machinery of wealth production and exchange, to be operated for social service and not for private profits; and further, since the Socialist Party has always, both in the United States and Europe, opposed all forms of race prejudice, that the Negro should no longer look upon voting the republican ticket, as accepting the lesser of two evils, the Republican and Democratic parties and select a positive good-Socialism.”4

For people to rally to a cause they needed to understand what was at stake and why an issue was worthy of attention and effort. Randolph understood that and used The Messenger to inform them.

Informing people of the injustices going on, such as unfair employment practices for blacks including low wages, was not enough. Randolph felt that action had to be taken, but how? The answer would lie at the door of the largest employer of blacks at the time: The Pullman Company. Randolph supported blacks’ entrance into the house of organized labor. He was approached by Ben Webster to help the Pullman Porters organize a union. He quickly agreed. Organization of the labor force was the next logical step for Randolph, so why not go for the largest black labor force? This was an attractive situation for the porters of the Pullman Company because Randolph was not employed by the company and could not be threatened or fired. Previous attempts to organize a union had been quashed by firing or isolating any workers included in the activity.

Using the major hubs of the company itself, Mr. Randolph organized The Brotherhood Of The Sleeping Car Porters. It was created in secret at first until it could gain enough strength to be a formidable power structure of organized workers. This was difficult, especially since The Pullman Company regularly donated to black churches. It was a long drawn out battle fraught with difficulties. They began with a tiny membership and lacked recognition by the American Federation of Labor. Worse yet, in the beginning half of the 1930’s, they had to fight against anti union legislation. Finally, in 1935 they received a charter with the AFL. Juan Williams pens this about the BSCP “ For many years, BSCP members acted as “Civil rights Missionaries on Wheels’”5

The mass organization of working people to effect a social change was to become part of Randolph’s arsenal in his fight for civil rights. The blue print for social change now included mass information and the organization of like minded people. This also meant that through persistence and perseverance A Phillip Randolph was now leading the most powerful African-American organization in the United States at the time. He would face the problems of equality in the workforce with a greater understanding of what it took to create change and the exponential growth of the civil rights movement. Randolph would not waste the power of this position; he was about to discover the third and possibly most crucial part of his tools for change-- direct action.

After informing his constituents about their cause and creating organizations, the next step was to take direct action. The Great Depression was more severe for African-Americans because of white supremacist society. Eugenicists had easily convinced whites they were superior to blacks. Ku Klux Klan activity had been sparked to kill or scare away black workers. In the depression “no job was safe for blacks,” wrote historian Harvard Sitkoff. “White women replaced black men as restaurant and hotel employees and elevator operators.”6

The more the depression worsened, the more whites demanded blacks be dismissed. Violence against blacks in the south was one of the main ways white supremacists to took away their often menial jobs. Southern African- Americans also suffered as unemployment regulations were stringent and paid less to blacks than to unemployed whites.

In the 1930’s huge steps were taken to create the foundation for the civil rights movement. Writer Paul Moreno says about the situation of African-American politics at that time, “In the 1930’s black Americans, although devastated by economic disaster, gained influence in national politics by means of a more mature Negro press, national organizations like the NAACP, and a greater union presence, and a measure of voting power in northern cities.”7 In the early 1930’s this voting power was focused by the NAACP and the black press by giving information on which candidates stood for black rights. In New York City, voters elected the first two black judges in Harlem as well as black state legislators. Rather quickly, the black vote shifted from the traditional Republican to the Democratic, as urged by The Courier, the largest selling black newspaper . “My friends go turn Lincoln’s picture to the wall”, wrote publisher Robert L. Van “that debt is paid in full.”8 With these hard earned civil rights building blocks in place all that was needed was an opportunity to present itself to spark change.

The opportunity for change did present itself in the form of the defense industry boom. With World War II in progress there was a huge demand for labor in the defense industry. The biggest problem was that African Americans were among the last to get hired if hired at all and their jobs were almost always menial. Due to the political and social building blocks set down by the defense industry and the employment opportunities that were opening up because of the war, it became evident to black leaders that the time had come to fight for equal employment rights. The main focus of their demands would be defense and government jobs.

Moreno who wrote From Direct action to Affirmative Action, writes about the period,

”when Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Defense Advisory Commission in May 1940, to advise him on manpower use, he appointed Robert C. Weaver to its staff, but the board only “recommended” nondiscrimination in the defense industries…black Americans were left out of the burgeoning defense boom and training programs, and remained segregated and held the most menial jobs in the armed forces.”9

The question that was on many African-American’s minds was how to bring about this change? How to organize in such away as to get government to act while the defense boom was going strong?

Many social theories point out the stages movements go through to produce results. Almost all social movements go through a bureaucracy phase. This is certainly indicative of the civil rights movement. Although there were many splits among black leaders on how things should be done, most agreed that previous success included organization and negotiation. Again at the forefront of the movement was A. Phillip Randolph, president of The Brotherhood Of The Sleeping Car Porters, who would demand presidential action to remedy discrimination in the defense industry and the armed forces. Randolph was fighting a war on two fronts. One front was within the labor movement itself: the many national unions still did not allow black representation. The second was political: the need to negotiate presidential action to end defense and military discrimination. The latter would come to a head at the White House on June 8, 1941, when Roosevelt met with Randolph and other civil rights leaders. Randolph had organized a movement that had held mass rallies in major cities and was ready to execute a massive march on Washington unless their demands were met. Roosevelt reacted by offering to make some calls to factory heads bu Randolph responded, as Ronald Takaki writes: ”people are being turned away at factory gates because they are colored. They can’t live with this thing. Now, what are you going to do about it?” 10 Roosevelt resisted, not wanting to forced into action. When Randolph revealed that the march would involve a hundred thousand African Americans marching in the streets of Washington, Roosevelt knew that with the kind of international attention that would draw he would have to issue an executive order. He issued Executive Order 8802, requiring an end to discrimination in defense industries.

The order did not, however, end segregation in the armed forces. When Randolph called off the march he received a lot of criticism for not having all of the demands met. In an article in the socialist newspaper, The Militant, Albert Parker wrote, ”Everything that Randolph and White said a week ago about the memorandum still applies today. It is not a proclamation or an executive order which would give assurance of discontinuance of discrimination. What the negro want now is action, not words.” Randolph said last week,” Let the masses speak!” But now he says, “I’ll decide the question not you.”11

The difficult decision to call off the march had to be weighed against what the movement did get, which was an executive order that met half the aims of the meeting. Although there was not really anything in place to enforce this order, it was there none-the-less. Randolph recognized this as a stepping stone to the next phase, which was to desegregate the armed forces.

It must be said that Randolph exercised amazing foresight when he kept the committees together that could organize such a march on Washington if ever it was needed. This would prove to be an invaluable part of Randolph’s blueprint to create social change. The fact that Randolph kept his word to President Roosevelt and called off the march demonstrated that he would keep his word. This would benefit him in future negotiations with the White House. After all, he had held up his end of a bargain and now had a history of being honest and fair in his negotiations. If he hadn’t called off the march, he would have lost almost all credibility as a leader and would not have had the later success with other executive orders and steps toward fighting discrimination.

Carlos Schwantes writes of changes for African-Americans in the wartime industry in the northwest:

“Tensions arose when black in the aircraft and shipbuilding industries applied for union membership. At Boeing the unions refused to admit them thus helping shape company policy Boeing never hired a significant number of blacks during the war. Kaiser who opposed racial discrimination, but many of his employees were members of the metal trade unions and had no desire to admit blacks to membership.”12

While the executive order was a powerful step in the right direction it lacked enforcement.

Randolph was already seeking the next opportunity to further the African-American civil rights cause. If nothing else, he was relentless and tenacious. Despite critical viewpoints he still negotiated the end of segregation in the armed forces. In 1948 Randolph was invited to the White House again along with Mary McLeod Bethune, Charles Houston and other African-American Leaders. Jervis Anderson writes of this encounter and how Mr. Randolph spoke forcefully to President Truman:

“ As Randolph remembers, the meeting had been proceeding smoothly and amicably, until he said to Truman,’ Mr. President, after making several trips to around the country, I can tell you the mood among the Negroes of this country is that they will never bear arms again until all forms of bias and discrimination are abolished.”13

Randolph again demanded that an executive order be issued to end segregation and discrimination in the armed forces. His demands were politely dismissed.

Randolph would have to use the possibility of nonviolent civil disobedience to end segregation in the armed forces. Non-violent civil disobedience would be drafted as part of Mr. Randolph’s blueprints for change. He would testify at the hearings for the universal military training bill, and once again he spoke to Senator Wayne Morse with unwavering determination. “We would participate in no overt acts against our government… ours would be one of non-resistance. Ours would be one of cooperation; ours would be one of non-participation in the military forces of the country…”14 He continued working his civil disobedience campaign advising black men to refuse induction into the armed forces. At the same time, Herbert Humphrey was pushing for a civil rights platform for Democrats, and once again the African-American voter would play a role. President Truman needed to retain the black voters and issued executive Order 9981, to end racial discrimination in the military.

When Randolph found that Truman’s interpretation of the bill ended segregation in the military, he congratulated the President on his “high order of statesmanship and courage.”15 Once again Randolph called off action because of presidential action, and once again he came under severe criticism for not following through with the civil disobedience campaign.

16

16

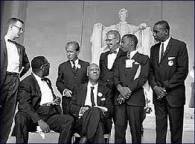

In August, 1963, Randolph’s social blueprints reached a s\pinnacle of accomplishment and completeness when over 250,000 marched on Washington. Juan Williams wrote of Randolph: “For Half a century Randolph was at the forefront of grass roots efforts to improve the lives of black Americans.”17 He had helped to lay the foundation for this occasion and was able to see his efforts come to fruition. He had become the elder statesman and advisor to the civil rights movement. He was one person among many who worked long and hard for change. He defied oppression and left a clear set of blueprints for positive social change. He informed, organized, negotiated ,planned direct action and civil disobedience. Change did come through organized struggle, which still continues. Most importantly he left behind a plan and deep footsteps for future leaders to trace- a set of blueprints.

18

18

Bibliography

1. Photograph A Phillip Randolph with President and Mrs. Roosevelt;

http://withintheblackcommunity.blogspot.com/2011/02/brief-history-of-black-people- speaking.html: March 1, 2011

2. Takaki, Ronald. Double Victory A Multicultural History of America in World War II.

Boston: Little, Brown , 2000. P. 41

3. Wilson, Dr. Sondra Katheryn, ed. The Messenger Reader: Stories Poetry & Essays

From The Messenger Magazine. New York: Randomhouse, 2000. p. 353

4. Ibid. p. 347

5. Williams, Juan. Eyes On The Prize Americas civil rights years, 1954 -1965. New

York: Penguin, 1987. p. 197

6. Sitkoff, Harvard. A New Deal For Blacks: The Emergence of Civil Rights As A

National Issue: Vol. I The Depression Decade. New York: Oxford University Press,

1978. p. 27

7. Moreno, Paul. From Direct Action to Affirmative Action. Louisiana: Louisiana

State University Press, 1997. p. 67

8. Sitkoff, Harvard. Op. cit. p. 65

9. Moreno, Paul. Op. cit. p. 67

10. Takaki, Ronald. Op. cit. p. 41

11. James, C.L.R., Breitman, George, Keemer, Edgar. Fighting Racism in World War II.

New York: Monad Press, 1980. p. 117

12. Shwantes, Carlos A. The Pacific Northwest An Interpretive History. Lincoln: The

University of Nebraska Press, 1989. p. 417

13. Anderson, Jervis. A. Phillip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait. Berkley: University

of California Press, 1972. p. 276

14. Ibid. p. 278

15. Ibid. p. 281

16. Williams, Juan. Op. cit. p. 197

17. A. Phillip Randolph at Lincoln Memorial, http://www.whitehousehistory.org/.whha

Classroom/images/classroom 9-055.jpg&imgrefurl. March 1, 2011

18. A. Phillip Randolph with Map, http://image1.findagrave.com/photos250/photos/2008/324/6137907_122719558207.jpg&imgrefurl=; March 1, 2011