http://dschwa.glogster.com/davids-glogester/

A Hand Up

by Cindy Raves

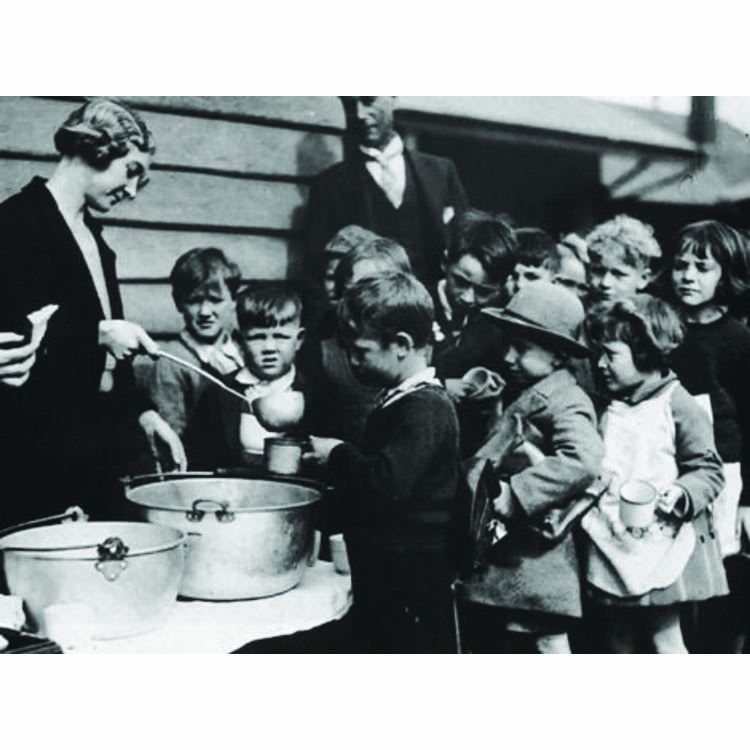

“I was so jealous of my friend Shirley,” my mother, Sally Baxley, said. “Her family had mustard and onion sandwiches for dinner. I thought they must be so rich. We usually had watered-down potato soup.” During the depression, my mother’s life changed overnight. One minute she was living a comfortable, middle-class life and the next she was learning what it was to be hungry. An estimated 50% of children during the Great Depression did not have adequate food, shelter, or medical care and many suffered rickets.

“An exciting day in our neighborhood was the day that a neighbor who worked at the Los Angeles County jail brought home a huge pot of beans,” my mother said. “All the neighbors went to his porch with pans and he filled them up. It seemed like we were having a feast.”

http://dschwa.glogster.com/davids-glogester/

The Great Depression was a dark period in America’s history. “On “Black Tuesday,” October 29, 1929, the stock market lost $14 billion, making the loss for that week an astounding $30 billion. This was ten times more than the annual federal budget and far more than the U.S. had spent in WWI. Thirty billion dollars would be equivalent to almost 4 trillion dollars in 2009.

During this time, one in four employable people were out of work and there was no hope of finding a job. These statistics, along with the heartbreaking stories of poverty, make what I used to see as just an esoteric notion of “The Depression” for my parents more concrete. Now, in my lifetime, the country is again facing an economic crisis. The problem may not be as severe as the one my parents and grandparents lived through, but again our government is faced with a failing economy and an astounding unemployment rate.

Photo from the San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library, Creative Commons.

Unemployment was the major problem during the 1930s. Not only was the jobless rate 25%, but also another 25% had to take wage cuts or were only working part-time. As a result, the gross national product fell by almost 50%. This lasted until 1941, when World War II was underway and the unemployment rate officially fell back below 10%.

The jobless rate during the current economic crisis is not as severe; still, the government is taking measures to avoid a repeat of the tragedy of the 1930s. In February 2009, Congress passed an economic stimulus package to try and help our ailing economy. The bill includes more than $150 billion in public works project for transportation, energy and technology.

When I heard about the President’s proposal, I remembered my father telling me that his family made it through The Depression with the help of a federal program called the Civilian Conservation Corps (Corps or CCC). The current jobs portion of the economic stimulus package is reminiscent of the CCC.

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a small but important part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. President Roosevelt began proposing the idea of the Civilian Conservation Corps during his campaign against Herbert Hoover. He was a strong nationalist who traced the depression to domestic causes.

It's ironic that the first "C" in the CCC refers to the "Civilian"

www.livinghistoryfarm.org

Touted as a “hand up, not a handout”, the CCC was an agency “created by Act of Congress on March 9, 1933 to furnish employment, vocational and citizenship training and educational opportunities for unemployed youth, to enable young men enrolled in the CCC to provide aid for their dependent families, and to advance a nationwide conservation program on forest park and farmlands.” These programs helped many families, including my own, survive during these destitute times of The Great Depression. President Roosevelt used progressive techniques to try and overcome the economic emergency by creating social programs to combat poverty. A small but important part of the New Deal, the Corps gave young men the opportunity to work, receive on-the-job training and further their education. The benefits to the National Parks and infrastructure are still evident today. For example, many bridges, dams and recreational areas all over the country.

It was the most popular of the New Deal programs with the American public. The CCC was “the third piece of emergency legislation to be sought by President Roosevelt to deal with the financial situation, authority for the Federal government to begin extensive public improvements.” The plan was to establish camps for young (18-25 year old) men to “receive in addition to their pay, quarters, food, clothing, medical attention and hospitalization.” The young men were paid a salary that was divided between a savings account, their family at home, and cash for their pockets.

Not everyone was on board with President Roosevelt’s plan to create the CCC. Organized labor worried about jobs being taken away from union employees and contracts being denied to public companies. William Green, the president of the American Federation of Labor, criticized the plan because he worried that it would “threaten the standard of labor.”

In addition, many in Congress opposed the plan. The bill that included the Corps was sponsored by both Republican and Democratic leaders; however it was “met with strenuous objection immediately after the plan was promulgated.” North Carolina Senator Josiah W. Bailey, among others, opposed the New Deal and the formation of the Corps. The opponents were upset that $20 million would be taken away from regular public works. Both labor and some members of congress were concerned that the Corps would drive down wages for regular workers.

Congress and other groups around the country were also worried that the programs had socialist aspects. The CCC received harsh criticism from conservative congressmen, who labeled it socialism. The American Liberty League felt the CCC was a scheme to mold youth into the “raw manpower for a colored shirt fascist army of Roosevelt the Dictator." Ironically, army officers attributed the problems with recruits at one of the first camps in Fort Dix, New Jersey, to “Communist agencies outside the camp”.

Even some local communities opposed the CCC coming to their towns. They feared that "bums" and "delinquents" would pollute the water, disturb the wildlife, drink, and ravage women. To calm these fears, the CCC established a publicity campaign, which sent camp officials to speak at Rotary Meetings and other local civic organizations. Enrollees were also encouraged to write essays for local newspapers to talk about their positive experiences in the program. Even with all of the anti-New Deal sentiment, the fact remains that many American families would not have survived without these programs.

Before the stock market crash, my grandfather was a successful contractor. His company was responsible for improving the highways between Florida and Georgia. He had two partners, but when the economy took a turn for the worse, one partner committed suicide and the other partner ran off with his share of the money. My grandfather paid the company debts and the salary owed to each employee and was left with nothing. His daughter (my aunt), who worked at a grocery store during The Depression, she would sometimes steal cans of soup, and stretch them into multiple meals by adding water, because food was so scarce.

My uncle and father both were chosen to work for the Corps and were able to send money home to help feed their family. My uncle went to California to help with the National Forests and my father went to Connecticut to pick tobacco. He told me they would not have been able to survive without the program. My father also attributed to his later successes later in life to the CCC.

The United States Army ran the civilian camps, even though the program was part of the Department of Labor. It was the only agency equipped to handle the residential needs the Corps would require. The recruits were on a strict schedule, up early in the morning, exercising and work all day. Not everyone in the camps enjoyed the experience. Some camps had bad cooks, or staff who would skimp on supplies and pocket the money saved. The “living quarters were also spartan, being open bay barracks the central feature of which would be a large pot bellied stove. Cold weather would be hard felt as would the heat of the summer month.”

Many different agencies were involved in the running of the camps. For example the Army ran the camps and the Department of Interior help determine what projects would be completed. Five hundred camps belonged to the Soil Conservation Service. These workers were responsible for erosion control. They were able to stop erosion on more than twenty million acres. The CCC also made incredible strides in developing recreational facilities in national, state, county and metropolitan parks.

Some recruits couldn’t handle the primitive living conditions and the military structure, so the desertion rate was a steady 8 percent. This jumped to 20 percent toward the end of the program, when other jobs became plentiful.

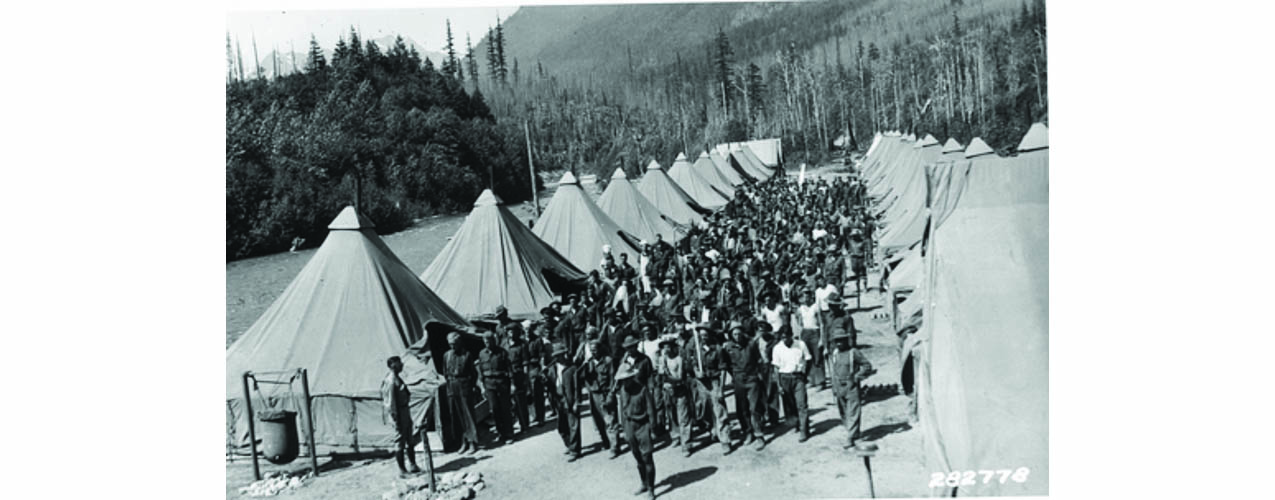

Skagit CCC camp, Mt. Baker National Forest, Washington

http://community.artofmanliness.com/profiles/blogs/manly-lessons-from-the-greatest-generation

To raise morale, as well as for publicity, some of the camps published a newspaper called “Happy Days.” Along with the news, the men contributed stories and poems. When I read excerpts I found it ironic that many of the submissions weren’t really that uplifting. For example, the following poem was written by D.E.M. from Arcadia, Rhode Island:

STUMPS

I hope that I shall never see,

A stump outside the CCC;

A stump whose wiry roots are found

Deep in the earth’s tenacious ground,

A stump at which I slave away,

All during a torrid summer day,

Stumps are dug by guys like me

And other in the CCC.

Based on my reading, digging stumps was a small part of the work that the men had to do.

The government had little trouble finding projects for the CCC to do. Most of the work was environmental. Corps members built fire towers and fire roads, they fought fires, and they planted more than three billion trees in the national parks. The Park Service has estimated that by 1935, the CCC had advanced forestry and park development by an estimated 10 to 20 years. The national parks in the United States would not be what they are today without the work of the Corps.

The CCC created the first state parks for Virginia, West Virginia, South Carolina, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Montana and New Mexico. In seventeen other states, parks were expanded. The conservation efforts of the program are estimated to have saved millions of dollars from annual losses caused by forest fires, tree diseases, insects, rodent infestation, and soil erosion.

The projects that the Corp completed were important to the count, but the fact that all of these young men learned marketable skills was equally beneficial. Many of the recruits had never worked before and had little if any education. They also acquired a disciplined work et hic. The camps gave them the opportunity to learn new skills, and when the work was done, they could advance their education. According to the director of the CCC, in 1941, “5,176 enrollees completed the elementary grades and received their eighth grade diploma while in camp.”

In addition to the economic and environmental benefits, the camps also had a positive impact on the justice system. Judge M. Broude of Chicago estimated that the CCC was largely responsible for a 50 per cent reduction in crime in that city, because it took boys off the streets and inculcated in them a sense of values. The New York Commissioner of Corrections attributed a similar decrease in juvenile crime to the beneficent effect of the Corps. This is in stark contrast to the fears of local communities at the beginning of the program.

I think the most amazing accomplishment of the program was that “250,000 young men were working within three months of its establishment.” The men arrived at the camps malnourished and the government was able to feed them, give them healthcare and enable them to send money home to their families. There was a push to make the CCC a permanent agency within the National government, but the program lost support.

The Corps came to an end in 1942 because the war effort for World War II was increasing employment opportunities, many states fought to keep the program. In fact, one legacy of the camps is the collection of state-run programs, modeled after the CCC, that continue to employ youth in community service, training and educational activities as well as some federal programs. One example of a federal program modeled after the CCC is Americorps. In the Vista handbook from Americorps, the organization explains its mission partially by describing the importance of the CCC. I wonder if President Roosevelt knew that his plan to help the country and the environment would have such a lasting and far-reaching effect.

In an effort to explain his reasons for creating the CCC, Franklin Roosevelt said, “First, we are giving opportunity of employment for a quarter of a million of the unemployed, especially the young men who have dependents. Let them go into forestry and flood prevention work. That is a big task because it means feeding and clothing and caring for them. And we added twice as many men as we had in the regular army itself. And in creating the Civilian Conservation Corps, we are killing two birds with one stone. We are clearly enhancing the value of our natural resources. And, at the same time, we are relieving an insatiable amount of actual distress.” The personal stories of the positive effects of the program are heart warming.

A World War I veteran, when asked how his family had benefited from the CCC, said, “I have a stepson who was just eighteen when the first call came in 1933 and he went.” His step-son dropped out of high school in his junior year to join the Corps to help his struggling family because the veteran was out of work. When the boy joined, he barely passed the physical, but when he returned, “He came back a strong, healthy young man, full of fire and vigor, to finish school…all due to the magnificent training of the CCC.” Another legacy of the CCC was getting young men back into physical shape to be able to work in the private sector. Many came to the camp undernourished and left as healthy contributing citizens.

The program was not perfect by any means. More than 200,000 African-American enrollees were segregated after 1935 but received equal pay and housing. Black leaders lobbied to secure leadership roles. After receiving criticism from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People the camps were desegregated in the Northern states but remained segregated in the South. I am appalled at the policies that were in place and hope these recruits and their families benefitted as my family did.

My father, a CCC veteran, went on to join the Army as a clerk typist. When he was discharged, after the Korean War, he married my mother and began working at the Los Angeles Times as a pressman on the night shift. He became involved in the push to unionize. There were phone calls to our home with death threats, but my father and his co-workers did not back down and were successful in unionizing. This experience led him to go to law school. He worked the night shift and went to school in the day. He attributed his strong work ethic to his experience in the CCC. Eventually, in 1979, Governor Jerry Brown appointed my father- the hungry boy from the depression- judge. This might have never happened if it weren’t for the Corps. The camp benefitted many generations of my family.

In 2010, with the failing economy and an astounding unemployment rate, the present administration’s stimulus package makes sense.

Baxley, S. (2010, October 25). (C. Raves, Interviewer)

Dawley, A. (2003). Changing the World: American Progressives in War and Revolution. Princeton: Princeton Univeristy Press.

Economic Stimulus (Jobs Bills). (2010, December 15). Retrieved February 5, 2011, from New York Times: www.nytimes.com

Economist Discusses 2009 vs. the 1930s. (n.d.). Retrieved February 5, 2011, from Augustana College Web site: www.augustana.edu

Emergency Conservation Work. (1934). Second Report of the Director of Emergency Conservation Work for th Period September 30, 1933 to March 31, 1934. Washington, D.C.: GPO.

Emergency Conservation Work. (1934). Second Report of the Director of Emergency Conservation Work for the Period Extending April, 1933 to June 30, 1935. Washington, D.C.: GPO.

Feinstein, S. (2006). The 1930s: From the Great Depression to the Wizard of Oz. Berkeley Hieghts, NJ: Enslow Pulishers, Inc.

Freedman, R. (2005). Children of the Great Depression. New York: Clarion.

Gower, C. W. (1976). The Struggle of Blacks for Leadership Positions in teh Civilian Conservation Corps: 1933-1942. Journal of Negro History , Vol. 61, No. 2.

Hill, E. G. (1990). In the Shadow of the Mountain. Pullman: Washington State UP.

Justin, J. (2009). James F. Justin, Civilian Conservation Corp Museum. Retrieved October 26, 2010, from www.justinmuseum.com/famjustin/c.c.c..hit.html

Lacy, L. A. (1976). The Soil Soldiers: The Civilian Conservation Corps in the Great Depression. Randor, PA: Chilton.

Leuchtenburg, W. E. (1993). The Perils of Prosperity 1914-1932. Chicago: Uniiversity of Chicago.

McEntee, J. J. (1941). The Civilian Conservation Corps. What It Is and What It Does. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Director.

Merrill, P. H. (1983). Roosevelt's Forest Army: A History of the Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-42 Montpelier, VT: Perry H. Merrill.

Paige, J. C. (1985). The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Nation al Park Service 1933-1942: An Administrative History. Retrieved February 25, 2011

Points of First Roosevelt Bill Aimed at Unemployment Relief. (1933, March 22). New York Times , p. 7.

Roosevelt Defers Public Works Bill. (1933, March 11). New York Times , p. 6.

Willis, B. (2008). Americorps Washington: Washington Reading Corps. Vista Member Handbook. Retrieved February 5, 2011, from Americorps: www.americoprs.gov/help/vistahandbook

Wolfskill, G. (1962). The Revolt of the Conservatives: A History of the American Liberty League, 1934-1940. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

“Economist Discusses 2009 vs. the 1930s.” Augustana College – Home. Web. 05 Feb. 2011. (http://www.augustana.edu).

Hill, Edwin G. In the Shadow of the Mountain: The spirit of the C.C.C. Pullman, Wash: Washington State UP, 1990. Print.

Feinstein, Stephen. The 1930s: From the Great Depression to the Wizard of Oz. Revised Ed. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers, Inc. 2006. Print.

“Economic Stimulus (Jobs Bills).” New York Times. 15 Dec. 2010. Web. 5 Feb. 2011. (www.nytimes.com). Print.

Leuchtenburg, William Edward. The Perils of Prosperity 1914-1932. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1993. Print.

McEntee, James J. The Civilian Conservation Corps: What It Is and What It Does. Office of the Director. Washington, D.C. January 1941. Print.

Dawley, Alan. Changing the World: American Progressives in War and Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003. Print.

Merrill, Perry H. Roosevelt’s Forest Army: A History of the Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-42. Montpelier, VT: Perry H. Merrill, 1981. Print.

“Roosevelt Defers Public Works Bill.” Special to the New York Times. New York Times 11 Mar. 1933: 6. Print.

“Points of First Roosevelt Bill Aimed at Unemployment Relief.” Special to the New York Times. New York Times 22 Mar. 1933: 7. Print.

Wolfskill, George. The Revolt of the Conservatives: A History of the American Liberty League, 1934-1940. Boston. Houghton Mifflin, 1962. Print.

Paige, John, C., The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History, 1985. Web. 25 Feb 2011. (http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/ccc/index.htm)

Justin, John. James F. Justin, Civilian Conservation Corp Museum. 2009. Web 26 Oct. 2010. Web. (www.justinmuseum.com/famjustin/C.C.C..hit.html).

Lacy, Leslie Alexander. The Soil Solidiers: The Civilian Conservation Corps in the Great Depression. Randnor, PA: Chilton, 1976. Print.

ECW, Second Report of the Director of Emergency Conservation Work for the Period Extending April, 1933 to June 30, 1935. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1934. Print.

ECW, Second Report of the Director of Emergency Conservation Work for the Period September 30, 1933 to March 31, 1934. Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1934. Print.