Barons of Decision

by Cindy Roaf

The better element of our citizenship should realize the dangers that confront every community and organize to combat them. The disturbing element should be treated with a firm hand; other communities will send them on their way and less protected places will suffer. If allowed to go on without any restraint we shall soon find our working people and business will suffer in what should be the most prosperous year of our history.

The disturbing element the Mason County Journal is referring to were the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a radical union condemned by other unions for their insurmountable wall of prejudice they created between capital and labor. To appreciate the impact the IWW had on the lumber industry, one must understand the demographics of their recruits and the antagonistic style this union used to organize. The members of the IWW were mainly migrant workers from lower socio-economic levels. Using tactics such as work stoppages and violent attacks on nonmembers, this radical union spread their message of revolution against the capitalist society and promoted the “dictatorship of the proletariat”.

The Industrial Workers of the World brought trouble to the Mason County area as a lawless element into this small logging community unprepared for such agitators. As World War I loomed on the horizon, the IWW increased its presence while the US Government intervened with its own program which eventually would be the catalyst that helped change the face of the lumber industry in the Pacific Northwest.

The timber industry in the Olympic Peninsula during the early 20th century was rugged and violent. Loggers from the east migrated to the Northwest because the timber harvest was so abundant. Often faced with dangerous conditions, the men, known as timber workers and loggers, endured long hours, less than suitable living conditions and were isolated from civilization for long periods of time. Because the Northwest had an abundance of trees, land and men in the forest, the logging companies, like Simpson Timber Company earned immense profits but passed little on to the loggers. Many of the lumber workers did not have any particular ties to one place or area and frequently moved on whenever it suited them. The isolation and transient lifestyle of timber workers made union organizing extremely difficult.

Prior to the entrance into World War I, there was a surplus of labor due the increased number of new residents arriving in the Mason County. Those who were fortunate enough to have a job, would not protest against unfair wages and long hours giving the company the upper hand in the lumber industry. Union organizing in the timber industry was nearly nonexistent in the Olympic Peninsula prior to WWI. In the hostile environment created by the timber barons, many of the small unions were unable to last or make significant changes in wages and working conditions. Even unions such as the IWW tried to infiltrate the woods, sending in individuals to test the waters for organizing. This proved too be a very dangerous job, as seen here in a letter from the General Manager of Simpson Timber Co. 1911.

It is very difficult to eradicate this element entirely from our employees as they are certainly actively engaged in soliciting membership and stirring up discontent. For instance: Last week we had the misfortune to kill a man, and we had no idea until after he was dead that he was a member of this order, but found his membership card and by-laws among his effects.

The IWW was not welcome in the camps, and to provoke the timber barons could result in loss of life.

By 1917, the United States entered World War I. With the booming wartime economy, labor turned into a prime commodity. The IWW quickly focused its attention on the lumber industry when they saw the leverage the logger had on the timber barons due to the demands of war. For the overworked loggers, the IWW was a remedy to their fight against the poor working conditions and low wages. With its ability to bring together a union and organize a strike, the IWW created pro-labor propaganda in attempts to persuade the local communities to support their efforts. However, as a result of all the work stoppages precipitated by the IWW, many people including the local authorities and employers denounced the IWW for its un-American propaganda and radical behavior.

Due to the War, the US government needed warplanes and ships to fight in Europe but lacked the raw materials to build a strong air force. The Pacific Northwest was one of the few areas that produced the much-needed spruce lumber to build a powerful fleet of war planes and ships. With the government’s need for increased lumber production, labor troubles became complex. The draft and demands of wartime industries such as shipbuilding created a shortage of labor, which resulted in the recruitment of forest engineers and a number of experienced loggers and sawmill men to Mason County. This opened the door for the IWW to increase its organizing. They were able to take full advantage of the situation to create labor unrest in the Olympic Peninsula and throughout the Pacific Northwest.

The Simpson Timber Co., located in the small community of Shelton, Washington, had several logging camps in the old growth forest near the Olympic Mountains. Many of the residents in Shelton worked in the logging camps to support their families living in town. With the new demand of increased lumber production, the IWW increased its pressure on the workers to become members of this organization to build strength in numbers and to encourage loggers to strike for better wages and working conditions.

However, these soap-box agitators tried to force their influence upon an unsympathetic community during a time of extreme patriotism. The IWW’s fight created turmoil when the timber barons believed they were responsible for spiking saw logs at the mills, creating mysterious forest fires and stories of workers being beaten. This caused the timber barons to close the logging camps and sawmills, which put many men out of work. To the people of Shelton these unionist were anything but patriotic as recorded in the Mason County Journal July 27th, 1917,

The propaganda is appealing to men with no family ties and upon whom the duties of citizenship fall lightly, if at all: eight hours work for ten hours pay; then six hours; then no work, control of industry, and life without labor.

With the increased threats of violence and the impending strike from the IWW, all but one Simpson camp was closed down. The workers were relieved to be out of work during these tumultuous times. Though some loggers supported the IWW’s goals, others felt threatened by the organization’s tactics and left the camps on their own terms. The Mason County Journal, July 20th, 1917 reported,

"While less than half the men who have left the camps are members of the organization the others have been intimidated, or else have funds to prefer to take it easy until things quiet down or work is necessary again."

Unfortunately, the fight between the IWW and lumber barons would not come to an end so soon. When the lumber strike became inevitable in 1917, fear quickly spread across the community and the Olympic Peninsula. The IWW pushed for the lumber industry to give in to their demands for better working conditions, better pay and an eight hour work day.

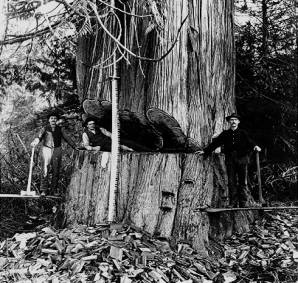

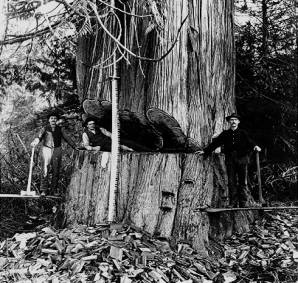

The loggers who cut down trees were called fallers. Using their axes, they cut notches in the trunk for springboards. They then stood on the springboards and felled the tree with a crosscut saw. Cutting above ground level was easier because the trunk was narrower, and there was less pitch to gum up the saws. Even so, it might take two days of hard work to cut down a large tree. Photo Credit: Darius Kinsey.

A Solution to the Lumber Strike

As the need for war materials increased the U.S. government felt the pressure to seek a solution to the lumber strike. Col. Disque, who had a long history with the armed forces and a reputation as being good with labor relations was assigned to bring an end to the lumber strike and “bring the lumber supply up to standards for the army”. As the new lumber czar, Disque was convinced the lumber barons “were genuinely interested in reform and the IWW was what stood in the way of a better life for workers and increased output of spruce”. Under Disque’s leadership, the creation of the Army’s Spruce Production Division was born. The program was responsible for building sawmills, railroads, recruiting laborers, and filling open positions with army soldiers. These woods soldiers were to remain neutral, neither favoring the lumber owners nor the unions, at times overseeing sawmills against the threat or reality of industrial sabotage by the IWW.

The labor relations continued to be an intense battle between the timber barons and the workers. Col Disque saw this as an opportunity to solve the labor disputes. Although Disque held anti-union beliefs, he did sympathize with some of the loggers’ desires for better working conditions. However, he deeply believed that, “All sides were selfish and neither shows any patriotism”.

After studying the situation and conferences with industry men, Disque concluded that some of the IWW demands would have to be met to improve production. Working with Mark Reed, General Manager of the Simpson Timber Company and a trustee of the United States Spruce Production Corporation, they both became convinced that the eight hour day should be accepted. In 1918, a meeting was called with the Mason County loggers to offer the eight-hour work day and reforms in camp conditions. Although it looked to be a victory for just the loggers, Disque would benefit from these changes as well. With the timber barons’ support, Disque created a grassroots organization in opposition to the IWW.

As the lumber strike continued through the fall of 1917, Disque changed his direction from fighting the union, to creating this new organization that would allow employers and employees come together for the common good.

The Creation of the 4Ls.

Image shown: "Detail view of riving 4056-foot log, showing use of Griffith jack, wedges and fibre-cutting iron, brush and timber back. Sept. 1918," Spruce Production Division operation.

In the spirit of patriotism, The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen (4Ls) was created. Local workers were put back to work, working side by side with the woods soldiers under a newly formed organization that would resemble a labor union. With the creation of the 4Ls, spruce production increased and the strength of the IWW all but disappeared. The tension and fear within the local communities had eased with the newly formed government union; unfortunately this would not last long.

The loggers who joined the 4Ls had to be anti-wobblies or they would not be hired. Col. Disque went even further and established a pro-American community to maintain American prosperity through nativism, patriotism and anti-communism. This was Disque’s solution for labor unrest and squashing the IWW. The anti-wobbly sentiment worked well in establishing the community by eliminating the radicals by persecuting anyone who held their beliefs. Ironically, the central focus of the 4L community was the ideals of democracy, equal rights, and patriotism.

This is a nice old WW1 Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen Badge. The badge features a forest, a ship, an airplane and a logger with Authorized by the Secretary of War. It symbolizes the need for spruce lumber for the war effort.

The 4Ls – saint or sinister?

Though most historical texts refer to Disque’s 4Ls union as a civilian organization that would outlast the war and bring industrial peace to the embattled Northwest, there were others who said that the 4Ls stood for “little loyalty and large loot”. Soldiers were placed in camps where lumber was not being produced which made it evident to the IWW that the real objective was to break the lumber strike. Army officers and woods soldiers were used to organize the newly formed union by increasing membership through terror tactics. All enrollees had to sign a loyalty oath and agree not to strike. Enrollees could be members of the IWW or AFL, but they had to promise not to organize workers into any union other than the legion. Anyone who would not join the 4Ls were accused of being a communist, a traitor and pro-German. These workers were immediately fired from their job and beaten by soldiers. Those who spoke out against the 4Ls, could be found hanging from nearby trees. Some would be threatened with a forceful airborne ejection from a speeding train they were riding if they declined to sign. Taking advantage of the state of public opinion during the war, Col Disque used the hatred of the IWW to continue his reign of terror under the disguise of military discipline. The local communities who feared the radical tactics of the IWW, now found themselves feeling uneasy with Col. Disque and his lumber dictatorship.

As the lumber production increased, Disque began to make enemies among the timber barons because of his power-hungry and selfish determination to be the victor in the labor dispute. He threatened to commandeer lands, mills or whatever else he deemed necessary for timber production. Despite the numerous accounts of terrorism and his power induced dictatorship of the woods, he was given credit for successfully urging the implementation of the eight-hour work day; medical facilities and food were made available to all timber workers.

These measures substantially increased spruce production in late 1917 and early 1918. However, after the war, timber executives tired of the Disque’s threats assumed leadership of the legion and turned it into a conservative, industry-wide company union.

In 1919, the United States Congress investigated charges of corruption, favoritism and that Disque and the legion had treated IWW and AFL (American Federation of Labor) members unfairly and spent too much money to accomplish limited results However, with the help of the United States Spruce Production Division Corporation, he was exonerated and awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

Permanent Mark on Industrial Relations

To the extreme disappointment of the IWW, and the timber barons, Disque took credit for the improved working conditions in the timber industry. However, there were some discrepancies as to who should take credit for the change in working conditions and the new 8 hour work day. The 4Ls took credit because they felt positive changes were made in working relations with the timber barons. The I.W.W. believed they should have received the credit because of the timber strike and the timber barons said they gave in to their demands as a gesture of good will.

Although membership in the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen declined after 1919, its constitution, by-laws, code of practice, and working methods continued as the controlling factor in the lumber industry in the Pacific Northwest until the Great Depression. Nearly fifteen years after the close of World War I, one writer observed,

The basis of operation which General Disque set up for emergency purposes developed into the classic agency of labor relations in the timber industry.

The long lasting effects of the lumber strike and the creation of the 4Ls had a huge impact on the lumber industry and lumber production. The residual efforts of the spruce army helped prepare companies such as Simpson Timber for large scale logging due to the hundreds of miles of permanent rail lines making spruce and evergreen accessible. Although because of the accessibility, after WWII timber became scarce. This eventually led to one of the biggest timber agreements in Washington State. In 1946, Simpson Timber Company signed an agreement with the United States Forest Service that placed the company’s lands and adjacent national forest lands under unified management. This agreement gave Simpson Lumber all sales from the reserved area through 2046, transforming the logging industry in one small town and making a permanent mark on the Pacific Northwest.

Works Cited

“Agitator Closes Bordeaux’s Camp: I.W.W. Visits Camp Six and Calls out Loggers Tuesday.” Mason County Journal. 20 July 1917. Print.

Avery, Mary W. Washington, A History of the Evergreen State. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1965. Pg.231 – 241

Brice P. Disque photographs, PH159-[item number], Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1299

Canterbury, Chris. “A History of the International Union of Timberworkers: 1911-1923”, Seattle General Strike Project. Web. 1999.

Ficken, Robert E. and LeWarne, Charles P. Washington, A Centennial History. Seattle, University of Washington Press. 1988. (pgs.92-97)

“Give Trouble-makers No Rope.” Mason County Journal. 20 July 1917. Print.

Holbrook, Stewart Hall. Green commonwealth; a narrative of the past and a look at the future of one forest products community, Seattle: Printed by F. McCaffrey at his Dogwood Press, 1945. Print.

LeWarne, Charles P. Washington State, Seattle; University of Washington Press. 1986.

Mabel, Joe. Photo: 13 January 2006. The object itself would be circa 1917. Http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LLLL_brass_button.jpg

Mickelson, Eric. “The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumberman: The origins of the world's largest company union and how it conducted business”, Seattle General Strike Project. Web. 1999.

Rowan, James. “Victory, but not the Final Victory”, Industrial Workers of the World; A Union for all Workers. Web.

Reed, Mark to Ames, Edwin. Edwin Ames Papers, accession 3820-1, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest. http://www.acadweb.wwu.edu/cpnws/.

Spector, Robert. Family trees: Simpson's centennial story. Bellevue, Wash.: Documentary Book Publishers Corp., 1990. Print.

Thomas, Berwyn B. Shelton, Washington: the first century, 1885-1985. Belfair, Wash.: Mason County Historical Society, 1985. Print.

“The Strike Situation.” Mason County Journal. 27 July 1917. Print.

United States Spruce Production Corporation. History of Spruce Production Division, United States Army and United States Spruce Production Corporation. Portland, Or.,192

Williams, Gerald. The Spruce Production Division. USDA Forest Service, Forest History Today, Spring 1999. www.oregonencyclopedia.org/entry/view/sitka_spruce

Wilma, David. Mason County Thumbnail History, HistoryLink.org Essay 7730. Web. 30, April 2006.

“Give Trouble-makers No Rope.” Mason County Journal. 20 July 1917. Print.

Holbrook, Stewart Hall. Green commonwealth; a narrative of the past and a look at the future of one forest products community, Seattle: Printed by F. McCaffrey at his Dogwood Press, 1945. Print.

LeWarne, Charles P. Washington State, Seattle; University of Washington Press. 1986.

Holbrook, Stewart Hall. Green commonwealth; a narrative of the past and a look at the future of one forest products community, Seattle: Printed by F. McCaffrey at his Dogwood Press, 1945. Print.

Reed, Mark to Ames, Edwin. Edwin Ames Papers, accession 3820-1, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Center for the Study of the Pacific Northwest. http://www.acadweb.wwu.edu/cpnws/

Mickelson, Eric. “The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumberman: The origins of the world's largest company union and how it conducted business”, Seattle General Strike Project. Web. 1999.

Holbrook, Stewart Hall. Green commonwealth; a narrative of the past and a look at the future of one forest products community, Seattle: Printed by F. McCaffrey at his Dogwood Press, 1945. Print.

“The Strike Situation.” Mason County Journal. 27 July 1917. Print.

Agitator Closes Bordeaux’s Camp: I.W.W. Visits Camp Six and Calls out Loggers Tuesday.” Mason County Journal. 20 July 1917. Print.

Avery, Mary W. Washington, A History of the Evergreen State. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1965. Pg.231 – 241

Mickelson, Eric. “The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumberman: The origins of the world's largest company union and how it conducted business”, Seattle General Strike Project. Web. 1999.

Ficken, Robert E. and LeWarne, Charles P. Washington, A Centennial History. Seattle, University of Washington Press. 1988. (pgs.92-97)

Williams, Gerald. The Spruce Production Division. USDA Forest Service, Forest History Today, Spring 1999. www.oregonencyclopedia.org/entry/view/sitka_spruce

Mickelson, Eric. “The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumberman: The origins of the world's largest company union and how it conducted business”, Seattle General Strike Project. Web. 1999.

Spector, Robert. Family trees: Simpson's centennial story. Bellevue, Wash.: Documentary Book Publishers Corp., 1990. Print.

Holbrook, Stewart Hall. Green commonwealth; a narrative of the past and a look at the future of one forest products community, Seattle: Printed by F. McCaffrey at his Dogwood Press, 1945. Print.

Thomas, Berwyn B. Shelton, Washington: the first century, 1885-1985. Belfair, Wash.: Mason County Historical Society, 1985. Print.

Brice P. Disque photographs, PH159-[item number], Special Collections and University Archives, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1299

United States Spruce Production Corporation. History of Spruce Production Division, United States Army and United States Spruce Production Corporation. Portland, Or.,192

Avery, Mary W. Washington, A History of the Evergreen State. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1965. Pg.231 – 241

Avery, Mary W. Washington, A History of the Evergreen State. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1965. Pg.231 – 241

Ficken, Robert E. and LeWarne, Charles P. Washington, A Centennial History. Seattle, University of Washington Press. 1988. (pgs.92-97)

Mickelson, Eric. “The Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumberman: The origins of the world's largest company union and how it conducted business”, Seattle General Strike Project. Web. 1999.

Rowan, James. “Victory, but not the Final Victory”, Industrial Workers of the World; A Union for all Workers. Web.

Williams, Gerald. The Spruce Production Division. USDA Forest Service, Forest History Today, Spring 1999. www.oregonencyclopedia.org/entry/view/sitka_spruce

Wilma, David. Mason County Thumbnail History, HistoryLink.org Essay 7730. Web. 30, April 2006.