We've Got to Get Ourselves Back to the Garden

by Heather Seymour

Forty years have come and gone, yet Woodstock is still celebrated as the most important music festival in history. Hundreds of thousands of people from all walks of life joined together for this unique gathering of three days of peace and music from August 15 through 18, 1969. Even though the creation of the festival didn't go as planned, today, Woodstock has become a social and cultural phenomenon for multiple reasons. This includes the time and place it happened, the people who attended, the dedication of the promoters and organizers and the bands that played. But what ultimately proved to make it unique was the interest in public welfare over profit.

Leading up to that summer in 1969, the world experienced, and was experiencing, countless changes. Issues of racial tension throughout the country were still prevalent. Though strides had been made, things were becoming more turbulent after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination in 1968. Moreover, the war in Vietnam was on everyone's mind. Protests against the war and other social issues had taken people into the streets, most notably at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. For many it was hard to be hopeful with what was looming on the horizon. Jon Pareles, a journalist and Woodstock attendee, noted that "expectations about large gatherings of young people were low."

Not everyone was hopeless however. During the infamous Summer of Love in 1967, the "hippie subculture" had showcased itself and made the country aware of its presence. In 1969, it was "still largely self-invented and isolated. There were pockets of freaks in cities and handfuls of them in smaller towns, nearly all feeling like outsiders." However, it was only a matter of time before all of these "freaks" joined together into something bigger. Then, they would realize they were not "some negligible minority, but members of a larger culture."

Michael Lang, co-creator of the Woodstock festival, started out in one of these small 'hippy' communities. In 1966, he moved to Florida and opened a head shop, which became a center for the movement that was going on in the Miami area. Eventually, he got the idea for the Miami Pop Festival, which was a two day event that resulted in the largest festival crowd to date.

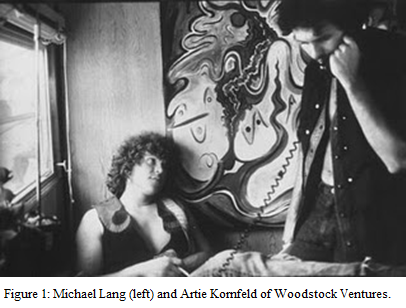

Lang later moved to New York after his shop was closed by Miami police. He then tried his hand at managing musicians. Through this endeavor, he met Artie Kornfeld, who was vice president of Capitol Records at the time. Kornfeld ran the East Coast "Contemporary Production." "I think I was the first company freak," he confessed.

Lang and Kornfeld became friends and eventually had the idea of opening a recording studio, as there were many popular artists in that region, including Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin. Lang and Kornfeld knew they would need financial backing for their idea. Through their attorney, they met with John Roberts and Joel Rosenman. Roberts and Rosenman were two "young men with unlimited capital looking for interesting, legitimate investment opportunities and business propositions." (Or so their advertisement in the local paper said). However, their idea of a recording studio would soon be pushed aside for something much bigger.

Through much consideration, Roberts and Rosenman felt that the recording studio would not be financially successful. Instead they were interested in a music festival. They figured they could use the revenue gained from the concert to build the recording studio later if they still desired. The four men formed Woodstock Ventures in which they were all equal partners.

Woodstock Ventures had a strong idea and the capital to back it. Now was the time to find a venue, book bands, and spread the word. Early in the festival planning process, Lang felt that they were on to something: "I had a feeling about it. I thought it was going to be more spiritual and special. I had grown up in the midst of the whole sixties movement...I knew that the people who were going to come were in the same frame of reference." However, anyone who knows even a little about the Woodstock festival knows that things never went as planned and the journey to this unique event would be a long one.

The young men decided on a location for the festival, Howard Mills Industrial Park in Wallkill, New York. But, before things even began, the citizens of Wallkill protested. They cringed at the idea of 'dirty, hippy kids' coming into their town. On July 2, 1969 the town passed a law that actually banned the festival from Wallkill. With the festival a little over a month away, the lack of venue was starting to make the event seem like a lost cause. And the panic wasn't only felt by the promoters. Negotiations with potential artists became difficult and even the locations selling tickets refused to continue.

Lang and the organizers began looking for another location frantically. Lang put ads in the paper and called just about everyone he knew, trying to find a replacement venue. Through various references, the organizers ended up in Bethel, New York on Max Yasgur's 600-acre dairy farm. After hard negotiations with the Yasgurs, Lang was able to convince them to hold the festival.

Lang knew this was the perfect location. "It was made in heaven," he confessed. In regard to the original location, he explained that the change in venue was meant to be. "It never felt comfortable . . . never felt friendly. The town itself and the surroundings were kind of hostile, to say the least."

Tirelessly, day and night, night and day, the organizers worked to construct the site. However, as the festival drew closer, it seemed that they had truly underestimated what was going to happen that weekend. Two days before the beginning of the festival, Wednesday, August 13, there were over 20,000 people camping near the stage. The crew had not been able to construct enough gates at that point, allowing the crowd to just walk right in. It was clear a serious issue was occurring. What would the promoters do about the amount of people already on the farm? How would they prevent more attendees from entering the field when there were no gates to keep them out?

The problems didn't stop there. On Friday, the first day of the festival, the amount of people pouring into Bethel caused a severe traffic jam. Many abandoned their vehicles and walked to the farm on foot. Musicians had to be flown in by helicopter. And by the time the show was supposed to begin, the first band had not received their instruments or gear. Frantic, the promoters tried to find a replacement, as they feared the crowd would become restless and partake in rioting. Eventually, the promoters found an artist to go onstage.

Richie Havens became the opener of the Woodstock Festival. At first he was reluctant, most likely due to the sudden change in set time or perhaps the size of the crowd, which had astonished him and many artists as they arrived. Regardless, he began to play and the crowd received him warmly, disregarding the late start and line-up change. Time went on and still no other artists were able to arrive to the site, forcing Havens to continue to play the remainder of his catalog. The crowd didn't seem to mind his multiple encores, but Havens was running out of songs to play.

Havens eventually had to start improvising. Right there on the Woodstock stage, he created the song "Freedom." He explains that it was what he felt. "The vibration was freedom." And the attendees could feel it too. More and more were arriving to the site, further shocking Lang and the other organizers.

Early on in the festival, the promoters realized they had to make a tough decision. The capital received for this festival was crucial to future Woodstock Ventures projects, including the recording studio. However, the amount of people flocking to the festival, in addition to those that had already arrived days before, was making it impossible to check tickets. And if they turned people away there surely would be violence. Lang and the organizers decided it would have to be a free concert. That the cost of violence, rioting and possible death was much higher than the needs of the financial backers. One of the promoter was not so pleased, "you're now giving the world's greatest three day freebie!" he exclaimed, upset about the loss of money. However, he when taken aside by Lang, he was forced to change his mind. Lang and Kornfeld wanted their dream to be a success and knew this was what had to be done.

"It's a free concert from now on. That doesn't mean that anything goes. What that means is we're going to put the music up here for free. What it means is the people who are backing this thing, who put up the money for it, are going to take a bit of a bath. A big bath...But what that means is these people have it in their heads that you're welfare is a hell of a lot more important, and the music is, than a dollar," shouted Woodstock's announcer to a sea of fans.

It was shocking to see the promoters and financial backers make a decision like this. They surely could have found ways to corral the crowd or stop those from entering without tickets. From the Woodstock documentary, you are able to see Lang and Kornfeld make this decision almost instantly. It was as if it was the only option. When asked about the situation, Lang and Kornfeld called it a "financial disaster," but that "it's hard to think on those terms when you have something like this." "This"indeed was becoming a beautiful sight where people were coming to experience a peaceful society and ultimately discover that they were part of a culture, a bigger society, and definitely not outcasts.

From that point on Lang and the organizers put the people first. They continued to spend more money to keep the attendees fed, healthy, and happy. And not only did it make for an interesting documentary, but it shocked the media who went on to chronicle the festival throughout the weekend, giving the world a play by play of the most important concert in history.

All throughout the festival, the theme was “togetherness”. Even when it rained the announcer coaxed them through it, telling them to take care of themselves and that things would get better. In spite of the terrible weather, the crowd stayed optimistic and even embraced it, sliding down muddy hills and frolicking with one another. If a concert was interrupted by rain today, most people would leave or become angry, however crowd was still happy to be on Yasgur's farm.

Due to the traffic, weather, lack of food and the number of people, it didn't take long before Sullivan County took notice. New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller ultimately declared Woodstock a disaster area. This resulted in more assistance for the attendees.

At one point, helicopters flew over the crowd, dropping dry clothes and flowers. More food was also arranged to be brought in. "We're all feeding each other," exclaimed one of the announcers, "there's always a little heaven in a disaster area."

Many doctors were brought in as well to service those who had overdosed on drugs or plagued with exhaustion. Ultimately, there were deaths at Woodstock. Different sources vary in their counts, but the majority agrees on three: one from a heroin overdose, one from a ruptured appendix, and another who was run over by a tractor while sleeping. Overall, the lack of violence in what was New York's second biggest city was statistically shocking.

The townspeople were also intent on helping the attendees. One town resident remarked that he felt it was his duty, that these kids were hungry and he was going to feed them. Why were the townspeople so generous to the individuals invading their neighborhood that had a negative reputation?

Over and over, the "kids" that attended were described as polite and friendly, frequently using words like "Sir" and "Ma'am." Many of the residents found their perspectives change, including the town's police chief: "I was very, very much surprised and I'm very happy to say, we think the people of this country should be proud of these kids... They can't be questioned as good American citizens."

Throughout the festival, Lang and Kornfeld were in awe of what they had created. From the lack of violence and overall compassion expressed by half of a million people in one place was remarkable. During the festival, Lang reiterated his feeling that something special and important was taking place: "This culture and this generation, away from the old culture and the older generation, you see how they function on their own. Without cops, without guns, without clubs, without hassle. Everybody pulls together and everybody helps each other and it works."

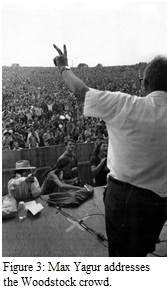

Even Max Yasgur, a man who was a member of that 'older generation', agreed that Woodstock was significant. At one point during the festival, he climbed on stage and addressed the audience:

"I'm a farmer. I don't know how to speak to twenty people at one time, let alone a crowd like this. But I think you people have proven something to the world... a half million young people can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but fun and music, and I God Bless You for it!"

Woodstock continued despite the chaos, with bands playing throughout the night on Sunday and into Monday morning. Jimi Hendrix was the final performer. By this time, much of the crowd had dissipated. Only about 25,000 were left to experience the most celebrated performance of the entire festival. His rendition of "The Star Spangled Banner" became one of the most famous and talked about moments of Woodstock.

"'The Star-Spangled Banner' just filled the air. It just sounded like the Vietnam War. It sounded like a firefight. It sounded like helicopters...He made it sound like everything that was going on in our country, and around the world at that moment," explains rock critic Billy Altman. Many thought it was unorthodox, even offensive. However Jimi had no ulterior motives, just to play something that he thought was 'beautiful.' At the time, it was controversial, but, to many, it redefined patriotism. It showed that just because you don't agree with the way things are doesn’t mean you are any less of an American.

Days after Woodstock ended it became apparent that the festival would never be forgotten. In 1970, a documentary was released, Woodstock: Three Days of Peace and Music, that chronicled the crowd, promoters and unforgettable performances. The film allowed those not present to feel like they were there and allowed those that were there to experience the entire weekend again.

There were many that wanted to go to the festival, but were unable to do so for various reasons. Joni Mitchell, who was advised by her manager not to play Woodstock , was one of these people that regretted missing this important event. After watching coverage of the festival on television she wrote a song, Woodstock. The song is heard in the documentary credits and was even covered by actual Woodstock artist, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. The song expresses what was felt by not only Woodstock attendees but by those with the realization that things were changing:

"I came upon a child of God/He was walking along the road

And I asked him where are you going/And this he told me

I'm going on down to Yasgur's farm/I'm going to join in a rock 'n' roll band

I'm going to camp out on the land/I'm going to try an' get my soul free

We are stardust/We are golden

And we've got to get ourselves/Back to the garden

Then can I walk beside you/I have come here to lose the smog

And I feel to be a cog in something turning/Well maybe it is just the time of year

Or maybe it's the time of man/I don't know who I am

But you know life is for learning...

By the time we got to Woodstock/We were half a million strong

And everywhere there was song and celebration

And I dreamed I saw the bombers/Riding shotgun in the sky

And they were turning into butterflies/Above our nation

We are stardust/Billion year old carbon

We are golden/Caught in the devil's bargain

And we've got to get ourselves/back to the garden."

The documentary was a commercial success. Its revenue, along with that obtained from other Woodstock merchandise, such as live recordings, covered all the expenses for the festival, and then some. It took nearly a decade to this, but there was no doubt in the promoters' minds just how iconic the name 'Woodstock' had become. But it didn’t stop there. Even the attendees were found to be a new target audience. At Woodstock, "hippy capitalism" was found all over in various types of concession stands and other products. Jon Pareles of the New York Times explains that while the festival was an escape for the reign of capitalism, afterwards the crowd was "quickly recognized as a potential army of consumers that mainstream merchants would not underestimate again. There was more to sell them than rolling papers and LPs."

All of these factors proved the need for more festivals of the Woodstock name. They could call them 'anniversaries' thus exciting people for the opportunity to experience their own Woodstock. However, in the end it would prove these festivals were not as much held for the fans as they were for making a profit, something that we had come to appreciate Woodstock disregarding decades earlier.

The first major Woodstock anniversary was in 1994. Simply called "Woodstock '94," it also was held at an outdoor farm-like location, close to the original site chosen by Lang. Some of the original Woodstock artists performed, including Joe Cocker. Even Bob Dylan decided to come, exciting the crowd and promoters due to his declined invitation 25 years earlier. The festival also proved to provide a who's who of popular artists of that era, including Green Day, Metallica, Nine Inch Nails, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

Although aspects of the festival, including the farm-like location, showed the festival was much like the original, there were many extra measures the promoters took this time around. As Karen Schomer of Newsweek described, prior to the festival, "plenty more capital-raising plans are in place: an album and a film, a CD-ROM, a $49.95 pay-per-view broadcast, scores of T-shirts, programs, posters and other merchandise." In addition, the tickets were $135 each and had to be purchased in sets of four. Not surprisingly, many of the original Woodstock generation criticized the new festival for "being too commercial and for squandering the spirit of '69."

Indeed, the original festival became famous for putting aside financial gain for the welfare and experience of the attendees. It was obvious that this time around Lang wanted to have the best of both worlds. He wanted to have a peaceful event but to make a substantial profit. And why couldn't he with a fresh new generation that had only heard of Woodstock from their parents or the movie? "The baby boomers had their Woodstock; now let's do one for those poor, alienated Generation Xers who get picked on all the time," explained Lang.

The actual concert is best remembered for its excessive rainfall. Two out of three days of rain caused a massive sea of-mud covering the attendees and even the artists, resulting in the festival's nickname, Mudstock . During Green Day's performance, the singer started a mud fight with the audience that resulted in fans jumping on stage. Things got heated and a security guard assaulted the bassist, assuming he was an audience member. Unfortunately moments like this overshadowed the rest of the concert, which was more or less similar to other festivals that had occurred to date.

Perhaps the baby-boomers were right. The festival was too commercialized and too hyped to ever live up to the unique three days of peace and love that occurred on Yasgur's farm. Not even the bands were into the Woodstock message. Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails admitted that the prospect of $250,000 to play a 90-minute set was too hard to pass up. "This way we can fund the rest of our tour." Henry Rollins of Rollins Band put it harsher: "It's going to be fun and everything...But it's nothing but these ex-hippies, or whatever they are now, making money that they were too high to make the first time. For the kids? They're doing it for themselves." If the artists were detached from the Woodstock ideals, how would their fans relate?

Not ready to throw in the Woodstock anniversary concert towel however, Lang and the festival organizers decided to hold a 30th anniversary festival, Woodstock 1999. Despite grumbles from the Woodstock generation, Woodstock 1999 did come to life. While it was sure to be an economic success, it proved to be at the worst costs.

Woodstock 1999 was held at Griffiss Air Force Base in Rome, New York. Reporter Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone, who covered the festival over the duration of the weekend, described the location as a "grim and depressing Cold War relic, a slab of concrete and barbed wire designed as a home for nuclear warheads." Already it was clear that the '99 festival would have a much different tone.

Once the festival actually began, it was wrought with problem after problem. The organizers realized there were many issues they failed to address or consider. For one, that weekend was unbearably hot, and there was no place from attendees to rest in the shade. On top of that, the crowd was not allowed to bring in water. Once inside the attendees realized that concessions were very highly priced with water bottles at $4 and food double that. As the weekend progressed, the attendees became more and more tired. All day they were forced to walk long distances around the venue in a muddy mess. Although this time it wasn’t rain that caused the mud. Leaky sinks and toilets created a soggy lagoon of human excrement that ultimately made the "air pungent and the mud toxic." Pair that with the heat and discomfort was sure to be felt by all.

Two of the era's most aggressive bands, Limp Bizkit and Rage Against the Machine, were some of the more popular acts at Woodstock 1999. During both artists' sets, the crowd became increasingly uncontrollable. Fred Durst of Limp Bizkit, during their song "Break Stuff," "actually asked the crowd to be violent," chanting "C'mon ya'll! C'mon ya'll!" After their set, the crowd was begged to part so that the injured could be retrieved.

Later, Rage Against the Machine took the stage. At the end of their performance, they infamously burned the American flag, further setting the tone and foreshadowing the true anti-establishment sentiment that was to emerge full force.

Things took a serious turn for the worse during and after the Red Hot Chili Peppers' performance. On Sunday night, while dozens of bonfires were already lit, the Red Hot Chili Peppers performed "Fire" as an homage to Jimi Hendrix. Meanwhile, the crowd proceeded to ignite just about anything they could find, setting the concert site ablaze. They also looted and vandalized concession stands and overturned cars. Many described the scene as a war zone. Kurt Loder of MTV described the scene: "There were just waves of hatred bouncing around the place."

At face value, it seemed the bands had been key in the violence that arose. Not only were their lyrics composed with aggressive messages, but their actions and statements on stage were equally as shocking. However, to accept this as a reason, while possibly viable, seems too easy. If we blame the music, we are ignoring the situations under the surface that caused such as different outcome over 30 years.

As Doug Vandenboom stated, the most striking aspect of the festival was not the violence, rioting or looting, but the hypocrisy surrounding the actual event itself. He explained that concert itself was the problem:

"The irony in Lang's and the rest of the sixties 'Peace-Love-and-Understanding' generation is that Woodstock 99 was the establishment. This concert was a capitalist machine. It exploited every single person that purchased a ticket, bought a bottle of water, bought a CD of the concert, or even performed for that matter."

The concert had turned into what the original attendees in 1969 were trying to escape. They were against capitalism and its effects. They entered Yasgur's farm without tickets, dressed how they wanted, did what they wanted and shared with one another. By looking at these aspects, we are able to see that the attendees in 1999 did the same thing. "The kids at Woodstock 99 acted the same way that the original Woodstockee's against capitalist oppression."

This can be seen not only by the 'kids' however, but from the bands as well. They too felt exploited by the promoters and organizers, who wanted the day's biggest acts to perform in order to draw in revenue, not only during, but after the concert. The bands sympathized with the concertgoers. From overpriced tickets and concessions, to poor facilities and apathy by the promoters to all of these issues, "the performers began to associate with the fans' sense of betrayal," explains Vandenboom. "The performers began to encourage the crowd to get excited, to get angry, and most importantly, to subtlety fight back against anything."

After the 1999 festival, Lang was asked if he would hold another Woodstock concert. He responded that it was unlikely. "It cost a fortune and it didn't make its money back." How pathetic of an ending to one of the most celebrated cultural events in our history. It is sad to see how much Lang has changed from his confessions backstage at the original Woodstock. He told the world that money didn't matter anymore when you had a gathering that special. It was sad that subsequent generations could no longer join together for three days of peace and music without being exploited by anyone and everyone trying to make a dollar. Most of all, it is sad to see the name 'Woodstock' continuously be tied to projects and merchandise that are, and were, nowhere close to expressing the ideals of those who made the journey to Yasgur's farm over decades ago. What began with the 1994 festival, excessive marketing and products, came to life full force in 1999. To many, Woodstock 1999 was a disaster and those who attended were a disgrace. But when looking at the festivals side by side, it is apparent that '99 did have a message and did express a new counterculture's views. They were unwilling to suffer for the profit of the promoters.

There may be a resurgence of Woodstock merchandise, and even concerts, with the impending 50 year anniversary of the festival on the horizon. Many of the original artists may still be around and will perhaps join together on Yasgur's farm to play once more for peace and love. None of the past reunions on the farm have included Woodstock Ventures and have gone relatively unnoticed. Many have been free. However small the audience that gathers, it shows that there is still hope for a resurgence of what happened at the garden.

The 1960s were wrought with political and social turmoil, however somehow a half a million people found the energy to trek to a random dairy farm in Bethel, New York and ultimately change the world. They didn't really come for the bands, they came for the experience. They came to be with people like themselves, who felt alienated by society. At subsequent Woodstock festivals, their kids did the same. Although, they found that their Woodstock was not like that of the prior generation, but a warped version bent on exploiting them, most notably in 1999. Though the events in '99 were shocking, it is unlikely it will ever take away from the legacy of Woodstock 1969. It was legendary and truly exemplified a society where peace, unity, love and understanding were possible.

Works Cited

"1969: Woodstock Music Festival Ends." BBC News - On This Day. Web. 01 Mar. 2011. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/august/18/newsid_2760000/2760911.stm>.

Baber, Cassaundra. "A Whole Different World." Utica Observer-Dispatch. 19 July 2009. Web. 10 Jan. 2011. <http://www.uticaod.com/news/x1885902783/A-whole-different-world>.

Coin, Glenn. "A Return to the Site of Woodstock '99 a Decade Later." The Post-Standard. 2009. Web. 27 Feb. 2011. <http://blog.syracuse.com/entertainment/2009/07/a_return_to_the_site_of_woodst.html>.

Eppridge, Bill. "LIFE: Members of Woodstock Ventures, Inc. " Life. Web. 05 Feb. 2011.

Fornatale, Pete. Back to the Garden: the Story of Woodstock. New York: Touchstone, 2009. Print.

Gaps, John. "Trent Reznor." Comcast.net Music. AP. Web. 01 Mar. 2011. <http://www.comcast.net/slideshow/music-woodstock/31/>.

Gordinier, Jeff, and Nisid Hajari. "This mud's for you." Entertainment Weekly 237/238 (1994): 108. MasterFILE Premier. EBSCO. Web. 30 Jan. 2011.

Makower, Joel. Woodstock: The Oral History. New York: Doubleday, 1989. Print.

Mitchell, Joni. "Woodstock." 1969. Audio.

Pareles, Jon. "Woodstock: A Moment of Muddy Grace." New York Times 5 Apr. 2009. Print.

Schoemer, Karen, and T. Trent Gegax. "Woodstock '94: Back to the garden. (cover story)." Newsweek 124.6 (1994): 44. MAS Ultra - School Edition. EBSCO. Web. 30 Jan. 2011.

Sheffield, Rob. "Rage against the latrines. (cover story)." Rolling Stone 820 (1999): 52. MasterFILE Premier. EBSCO. Web. 27 Jan. 2011.

Vandenboom, Doug Vandenboom. "Woodstock 99: A Marxist Analysis of What Went Wrong." 2003. Web. 27 Feb. 2011. <http://www.class.uidaho.edu/pop/Woodstock.htm>.

Weiner, Rex, and Deanne Stillman. Woodstock Census. New York: Viking, 1969. Print.

Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace & Music (Director's Cut). Dir. Michael Wadleigh. Warner Bros., 1970. DVD.

Woodstock '69 Photos from Bettmann Archive." San Francisco Bay Area — News, Sports, Business, Entertainment, Classifieds: SFGate. Web. 05 Feb. 2011.

"Former Syracuse Newspapers Columnist Recalls Woodstock '69, '94, '99 (audio Slideshow)." Blogs on News, Sports, Entertainment and Life in Central New York - Syracuse.com. 27 July 2009. Web. 27 Feb. 2011. <http://blog.syracuse.com/entertainment/2009/07/former_syracuse_

newspapers_columnis.html#incart_mrt>.

Makower 113.

Figure 1: Eppridge, Bill. "LIFE: Members of Woodstock Ventures, Inc. " Life. Web. 05 Feb. 2011.

Fornatale 17.

Figure 2: “Woodstock '69 Photos from Bettmann Archive.” San Francisco Bay Area — News, Sports, Business, Entertainment, Classifieds: SFGate. Web. 05 Feb. 2011.

Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace & Music (Director's Cut). Dir. Michael Wadleigh. Warner Bros., 1970. DVD.

"1969: Woodstock Music Festival Ends." BBC News - On This Day. Web. 01 Mar. 2011. <http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/august/18/newsid_2760000/2760911.stm>.

Gordinier, Jeff, and Nisid Hajari. "This mud's for you." Entertainment Weekly 237/238 (1994): 108. MasterFILE Premier. EBSCO. Web. 30 Jan. 2011.

Schoemer, Karen, and T. Trent Gegax. "Woodstock '94: Back to the garden. (cover story)." Newsweek 124.6 (1994): 44. MAS Ultra - School Edition. EBSCO. Web. 30 Jan. 2011.

Figure 4: Gaps, John. "Trent Reznor." Comcast.net Music. AP. Web. 01 Mar. 2011. <http://www.comcast.net/slideshow/music-woodstock/31/>.

Schoemer.

Sheffield, Rob. "Rage against the latrines. (cover story)." Rolling Stone 820 (1999): 52. MasterFILE Premier. EBSCO. Web. 27 Jan. 2011.

Vandenboom, Doug Vandenboom. "Woodstock 99: A Marxist Analysis of What Went Wrong." 2003. Web. 27 Feb. 2011. <http://www.class.uidaho.edu/pop/Woodstock.htm>.

Baber, Cassaundra. "A Whole Different World." Utica Observer-Dispatch. 19 July 2009. Web. 10 Jan. 2011. <http://www.uticaod.com/news/x1885902783/A-whole-different-world>.

Vandenboom.

Figure 5 "Former Syracuse Newspapers Columnist Recalls Woodstock '69, '94, '99 (audio Slideshow)." Blogs on News, Sports, Entertainment and Life in Central New York - Syracuse.com. 27 July 2009. Web. 27 Feb. 2011. <http://blog.syracuse.com/entertainment/2009/07/former_syracuse_newspapers_columnis.html#incart_mrt>.