The Emergence of Earth Day among the Social Movements of the Later 20th Century

by Jennifer Inman

What has become Earth Day started out as a demonstration, a grassroots effort to bring political attention to environmental concerns. Although Vietnam was front and center during the late 1960’s, the degradation of the environment was creeping its way onto the political stage. The Vietnam teach-in, which was popular on college campuses, proved to be a potent way to focus public concern through a grassroots movement. Though the idea of Earth Day was born into a time of napalm and social unrest, it was the political activism of the 60’s civil rights and Vietnam movements that laid the foundation and created a knowledge base perfect for a successful environmental movement.

Gaylord Nelson, senator of Wisconsin during the 60’s, had earned the reputation of the ‘conservation governor’ due to the many environmental reforms he enacted in his home state . However, he was troubled by the fact that these environmental issues were not on the national political agenda – as if clean air and water were of no concern to the rest of the nation. After being elected to Senate in 1962 , he struggled to bring the plight of environmental degradation to the attention of Washington D.C. with little success. It occurred to Nelson that if he could bring media and political attention to these environmental issue, that could all change. His strategy was to convince the president to go on a national conservation speaking tour. He discussed this with Attorney General Robert Kennedy who liked the idea. As it turns out, so did President Kennedy. The following year, Kennedy embarked on a five day, eleven state tour. Although this 1963 tour was not successful in putting the environment in the forefront of the political agenda, it was successful in creating “the germ of the idea that ultimately flowered into Earth Day”.

![]()

It would be six years before Nelson came up with a new idea, one that was wildly successful. In the mean time, society still struggled through political conflict. The civil rights movement had started in 1954 and had come a long way by the time Nelson was ready to fight his battle. By 1964, the Civil Rights Act was passed . This accomplishment was a major blow against segregation and racial injustice, but there was more work to be done. It was this same year that lunch counter sit-ins and boycotts launched all over the south, lead by James Lawson who is credited as the leader of the sit-in movement. As the southern field secretary of FOR (Fellowship of Reconciliation), he held workshops and traveled to college campuses to teach the idea of non violent protest. These lunch counter sit-ins were originally staged events as part of Lawson’s workshops. Participants were being trained to sit quietly and avoid confrontation while other participants acted the role of segregationist and taunted, poked and spit on the demonstrators. Non violent demonstration “was not for the faint of heart… it required discipline” .

This stand for non violence was not isolated to sit-ins. Martin Luther King Jr. believed in non violence and his voice was well heard in the civil rights movement. During the Freedom Rides of ’61, black bus riders were routinely assaulted for sitting in the front of the bus and using the front doors , but they were strong willed and held true to the non violent nature of the demonstration. Racial violence was particularly strong in the south, presumably because white southerners were unwilling to change, unwilling to give up their way of life, but most of all, unwilling to give up their power. When school segregation was challenged in the south, mobs were not uncommon, and even supported by government officials. One such example is The Little Rock Nine. Just nine black students were to be admitted to Central High, yet the Governor agitated the public so much against desegregation that mobs formed and the public supported him for calling on the National Guard to prevent the nine students from entering the school .

Little by little the civil rights movement collected victories. In 1965, the agenda held black voting rights. Selma, Alabama would be the stage. Once again however, the government was on the side of white southerners. A voting campaign to encourage black voters in Selma was so disliked by the government and white southerners that five hundred school children were arrested under the new anti-congregation law when they marched to the courthouse after Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested . As the situation in Selma escalated, King proposed a march from Selma to the capital city of Montgomery. This march would cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, but not on its first attempt. The mayor of Selma ordered the local police to block the bridge. The end result was a brutal assault on the marchers and became known as Bloody Sunday. After several attempts to cross the bridge a court ruling declared the marchers had a constitutional right to participate in the Selma-Montgomery march. They crossed the bridge on March 21, 1965 and the march swelled to 25,000 people by the time it reached Montgomery. President Johnson signed The Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965 .

All these major accomplishments were achieved under the practice of non violence. The goal was to draw attention to the issues and raise awareness of injustice in an effort to force change on a legal scale. The early 1960’s were full of social activism, not just for civil rights but also for the anti-war and peace movements. The Vietnam anti-war movement began to grow in power and importance. Although the U.S. had been involved in Vietnam since the 1950’s, it was during the mid 1960’s that the anti-war movement really kicked off. Like the Civil Rights movement, student led marches and demonstrations were prominent. In 1962, the largest peace  mobilization on Washington D.C. to date was lead by four thousand college students representing fifty seven colleges from seventeen different states. They marched from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to the Washington Monument . Although this march was

mobilization on Washington D.C. to date was lead by four thousand college students representing fifty seven colleges from seventeen different states. They marched from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier to the Washington Monument . Although this march was ![]() of little interest to Congress and other officials, the same would not be said for future marches. On Easter Saturday 1965, twenty thousand people circled the Whitehouse and then moved to the Washington Monument in the largest single anti-war demonstration that had yet been organized in the United States. This demonstration integrated black civil rights activists along with antiwar leaders. This union of protestors marched down the monument singing “We Shall Overcome” .

of little interest to Congress and other officials, the same would not be said for future marches. On Easter Saturday 1965, twenty thousand people circled the Whitehouse and then moved to the Washington Monument in the largest single anti-war demonstration that had yet been organized in the United States. This demonstration integrated black civil rights activists along with antiwar leaders. This union of protestors marched down the monument singing “We Shall Overcome” .

By April 15th 1967, the Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam was launched with the goal of match the ’63 march on Washington for civil rights . The mobilization marched with fifty thousand in San Francisco and two hundred thousand in Central Park and boasted an extreme diversity of attendants. It was during this mobilization that the new draft resistance movement was christened. During a ceremony at Sheep Meadow in Central Park, one hundred and fifty young men burned their draft cards . Although draft cards had been burned previous to this demonstration, the numbers had been small. For example in New York City, four days after demonstrator Norman Morrison burned his body in protest to the war, fifteen hundred people rallied as five pacifists burned their draft cards .

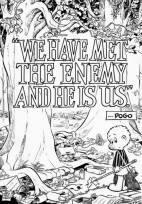

As public opinion for the Vietnam War dwindled, the government began to focus more strongly on boosting the image of American involvement with Vietnam, in an effort to walk the thin line of maintaining positive public opinion regarding the war. Public support fell from its pinnacle in 1965 with 57% approving the handling of the war to 42% in 1966 and 32% in 1968. Although these ratings were affected by the presidential election, they remained low even after Nixon was elected; just 43% approved of Nixon’s handling of Vietnam in 1973. As one would imagine, once Nixon announced withdrawal, opinion of his control of the Vietnam War skyrocketed to 75% . While the Vietnam War was actively being protested against the public became so disheartened that even the Vietnam Vets were against the continued struggle and demonstrated this by returning their decorations and purple hearts. One such event occurred on April 23, 1971 when seven hundred veterans threw their medals on the steps of the capital while solemnly stating their name and unit . “Quite simply the veterans had ‘identified the enemy. He is us’ the phrase was adapted from Walt Kellys comic strip character Pogo who had used it to describe the problem of environmental pollution. But it was especially poignant coming from soldiers who had found it so very difficult to identify the enemy in the field. ” This comic strip not only appealed to soldiers, but was adapted for use as posters on the first Earth Day in 1970 .

As public opinion for the Vietnam War dwindled, the government began to focus more strongly on boosting the image of American involvement with Vietnam, in an effort to walk the thin line of maintaining positive public opinion regarding the war. Public support fell from its pinnacle in 1965 with 57% approving the handling of the war to 42% in 1966 and 32% in 1968. Although these ratings were affected by the presidential election, they remained low even after Nixon was elected; just 43% approved of Nixon’s handling of Vietnam in 1973. As one would imagine, once Nixon announced withdrawal, opinion of his control of the Vietnam War skyrocketed to 75% . While the Vietnam War was actively being protested against the public became so disheartened that even the Vietnam Vets were against the continued struggle and demonstrated this by returning their decorations and purple hearts. One such event occurred on April 23, 1971 when seven hundred veterans threw their medals on the steps of the capital while solemnly stating their name and unit . “Quite simply the veterans had ‘identified the enemy. He is us’ the phrase was adapted from Walt Kellys comic strip character Pogo who had used it to describe the problem of environmental pollution. But it was especially poignant coming from soldiers who had found it so very difficult to identify the enemy in the field. ” This comic strip not only appealed to soldiers, but was adapted for use as posters on the first Earth Day in 1970 .

Each of the movements of the 60’s had its own demonstrations and protests, its own successes and failures. What makes this period of time especially interesting was how much progress was occurring, how so many issues were being tackled all at once. One issue just emerging into the public consciousness was environmental degradation. Leading up to the 1968 presidential election, environmental issues were of little concern. Both candidates focused on issues such as the war and the economy, with hardly a shout-out to environmental issues. In White House polls 1969 registered just a measly 1% of people who felt the environment was an issue to be concerned about and the Gallup polls logged public concern for air and water issues in 10th place . This was soon to change.

The environmental consciousness of the American public had been awakened with the 1962 publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. It took almost a decade before a mass movement was rallied behind environmental degradation, and Carson has been heralded as bringing “worldwide attention to the harm to human health and the environment.” Her book came out during the same timeframe that Senator Gaylord Nelson approached Kennedy to go on a national conservation tour. As the nation was struggling with civil rights and the Vietnam War, the young people were learning to be a generation of activists. Although the first conservation tour was unsuccessful, it was the knowledge and skills of these activists that helped pushed the environment onto national agenda and helped Earth Day to evolve from a single grassroots demonstration to an annual day of observance. By 1969, Nelson had found the niche to get the ‘germ of the idea’ out to the public and proposed a nationwide teach-in.

After touring the major oil spill of ’69 in Santa Barbara, Nelson read an article about the newly popular Vietnam teach-ins which were being held on college campuses. To Nelson this concept seemed an effective way to communicate the growing public concern to Washington D.C.. Nelson hoped to “tap into the environmental concerns of the general public and infuse the student anti-war energy into the environmental cause,” His goal was to “generate a demonstration that would force the issue onto the national political agenda. "

![]() By 1969, environmental problems were becoming hard to ignore. Air pollution was being linked with death in New York, huge fish kills were rampant in the Great Lakes with Lake Erie reported to be in its death throes, and the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland spontaneously combusted (for the third time!) as a result of the high levels of oils and chemicals it carried . The public was concerned and wanted change; the environmental movement was indeed underway.

By 1969, environmental problems were becoming hard to ignore. Air pollution was being linked with death in New York, huge fish kills were rampant in the Great Lakes with Lake Erie reported to be in its death throes, and the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland spontaneously combusted (for the third time!) as a result of the high levels of oils and chemicals it carried . The public was concerned and wanted change; the environmental movement was indeed underway.

It has been argued that the environmental movement gained importance mainly due to affluence. The U.S. became very prosperous over the 20th century and this prosperity translated into an American culture full of labor saving inventions (the dishwasher anyone?) and reduced work hours such as the 40 hour week and paid vacation time. This combination of “spare money and spare time created and ambiance for the growth of causes that absorb both money and time. ” In addition to this newly created ambiance, the activist emerged as a newly established ‘mass elite’. One that is “upper middle class – college-educated and youthful for its financial circumstances. ” This new activist had the means and the desire to create change and intended to be involved politically. With a generation of willing activists, and a public concerned with its environment, Nelson was ready to move forward with his efforts. During a Seattle conference later that fall, Nelson announced that there would be a nationwide grassroots demonstration to bring public awareness to the environment. It would take place in the spring of 1970.

Nelson was lucky to have many volunteers and organizers who had already “cut their teeth on other political issues of the 1960’s ” and were well prepared for this kind of a movement. Several weeks after the Seattle conference, Nelson created Environmental Teach-In Inc which was a non-profit, non-partisan organization aimed at coordinating a series of nationwide teach-ins on the environment during the spring of ‘70. This organization rapidly received monetary pledges from many organizations including the United Auto Workers, AFL-CIO, The Conservation Foundation and the Senator himself .

Nelson was lucky to have many volunteers and organizers who had already “cut their teeth on other political issues of the 1960’s ” and were well prepared for this kind of a movement. Several weeks after the Seattle conference, Nelson created Environmental Teach-In Inc which was a non-profit, non-partisan organization aimed at coordinating a series of nationwide teach-ins on the environment during the spring of ‘70. This organization rapidly received monetary pledges from many organizations including the United Auto Workers, AFL-CIO, The Conservation Foundation and the Senator himself .

Nelson chose former president of the Stanford student body, Denis Hayes, to be the national coordinator for Environmental Teach-in. Hayes had a very limited budget to plan a nationwide demonstration but he rented an office and selected a group of volunteers to help him. The country was split into regions, with especially promising volunteers each in charge of a different region. Even this early in the game, they received masses of mail and phone calls every day . Early on in the planning, Nelson and Hays agreed that the teach-ins should not be focused on college campuses, that wherever possible, they should be held in public spaces and that active participation should be sought from labor unions, the League of Women Voters and other social organizations. Even though many of the teach-ins did end up on college campuses, the effort was still successful in including the local community.

In an article published in November 1969, this environmental teach-in was described as a way for universities and local communities to come together to discuss “mutually shared environmental problems.” The article also described the versatility of the movement, with symposiums, conventions, rallies and panel discussions all focusing on the environmental issues pertaining to each region and school. The importance of the college educated youth is highlighted by Nelson when he was quoted stating “This generation of youth is vitally concerned about the environment, because it will inherit the disaster of years of wanton, indifferent waste and destruction of the natural resourced of the country. If something isn’t done soon, there may be nothing left for their children.” In addition to the wide support from students and educators, this day included “Labor union members, housewives, farmers, scientists, and politicians of all stripes—from Barry Goldwater to Edward Kennedy—made up the mosaic of faces in Earth Day crowds.”

Similar to other social movements of the 20th century, Earth Day gained prominence from the social diversity of the members who participated. The power of middle class women was utilized through the efforts of The League of Woman Voters (who have supported anti-pollution measures since the Progressive era) and other women’s groups such as the newly formed G.A.S.P. (Gals Against Smoke and Pollution). The United Auto Workers was active in mitigating the harmful effects of working conditions even before 1970, so when the national movement took off, it was not long before other labor unions such as the AFL-CIO joined in. Other major supporters were churches and religious groups (which also played a key role in supporting the civil rights movement), the science community which utilized the newly focused attention on ecological issues to showcase current research, and other professional and conservation groups such as the Sierra Club .

![]()

Several colleges had independently planned campus teach-ins, and Nelson’s idea to unite them proved genius. His staff announced the demonstration would take place on April 22, 1970 (chosen to fit into a college schedule between spring break and finals week) and would be called a ‘National Teach-In on the Crisis of the Environment’. This grassroots idea appealed to the new activist youth and far  exceeded Nelson’s expectations. It was in a full page ad placed by Environmental Teach-In Inc in the New York Times that the term Earth Day was born , a term that later became an annual holiday. The very first Earth Day drew an estimated 20 million Americans. Across the nation ten thousand K-12 schools, two thousand colleges and one thousand communities participated in demonstrations to raise awareness for the environmental problems plaguing the nation.

exceeded Nelson’s expectations. It was in a full page ad placed by Environmental Teach-In Inc in the New York Times that the term Earth Day was born , a term that later became an annual holiday. The very first Earth Day drew an estimated 20 million Americans. Across the nation ten thousand K-12 schools, two thousand colleges and one thousand communities participated in demonstrations to raise awareness for the environmental problems plaguing the nation.

Public support for a day dedicated to bring awareness to ecological issues was overwhelming. One shining example was New York City. The mayor supported the idea of Earth Day and lent his full power to closing down the city’s two main streets to motorized traffic in order to provide space for demonstrations, speeches and entertainment. Twenty NY City colleges and hundreds of K-12 schools held their own teach-ins while Manhattan expected a gathering of two hundred and fifty thousand. The city had over two hundred environmental groups which were united with the creation of the Environmental Action Coalition. The coalition worked to attract big names from the science, entertainment and business industries to participate in the day’s activities. Across the nation other activities ensued. In Seattle there was a planned environmental scavenger hunt to collect various samples of pollution and waste which were then to be presented to the legislature in Olympia. In California, a month long ‘survival walk’ from Sacramento to Los Angeles was planned and Detroit hosted a student picket of GM with a model transit system made of Volkswagen buses .

Nelson’s goal for Earth Day was to create a voice for the public’s concern about ecological issues and to use that voice to draw attention from Congress and Washington D.C. He succeeded. Not long after the April demonstration, the Environmental Protection Agency emerged and many environmental acts were passed. Earlier in the year, Nelson prepared a speech to his fellow Senate members advocating for an amendment to the constitution, an amendment to guarantee a decent environment for all. In his speech, Nelson proposed sweeping policy changes to include alternative energy, education, pollution control, recycling and public advocacy .

Of the twenty bills Nelson spoke of, more than half had made it through Congress by the mid ‘70s. The passing of NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) in 1969 set a national standard for “productive and enjoyable harmony between man and his environment” while the creation of the EPA in 1970 worked to enforce and maintain environmental policies. These political changes proved to be of great importance as they are still both very active today. The Clean Air Act and Clean Water Acts were both passed in 1972 and the Endangered Species Act that was passed a year later. None of these would have been proposed or passed if not for the public demand for a healthier environment. In order to conform to these new policies, stricter regulations were placed on many industries. Unleaded gasoline, a minimum MPG standard and the catalytic converter are all standards on vehicles today as a result of the stricter regulations. By the end of this ‘Environmental Decade’ twenty eight pieces of legislations were passed , creating the base of today’s environmental policy.

Of the twenty bills Nelson spoke of, more than half had made it through Congress by the mid ‘70s. The passing of NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) in 1969 set a national standard for “productive and enjoyable harmony between man and his environment” while the creation of the EPA in 1970 worked to enforce and maintain environmental policies. These political changes proved to be of great importance as they are still both very active today. The Clean Air Act and Clean Water Acts were both passed in 1972 and the Endangered Species Act that was passed a year later. None of these would have been proposed or passed if not for the public demand for a healthier environment. In order to conform to these new policies, stricter regulations were placed on many industries. Unleaded gasoline, a minimum MPG standard and the catalytic converter are all standards on vehicles today as a result of the stricter regulations. By the end of this ‘Environmental Decade’ twenty eight pieces of legislations were passed , creating the base of today’s environmental policy.

![]()

Earth Day started off as a political demonstration, a way to bring attention to a seemingly unloved topic. However, it has evolved into much more than just a demonstration. “What began in 1970 as a protest movement has evolved into a global celebration of the environment and commitment to its protection.” Though Earth Day celebrations have never matched those of 1970, the spirit lives on through the annual observance of Earth Day and the spread of the idea to Earth Week and even Earth Hour celebrations. For all the success attributed to the Earth Day movement, the highest success was the foundation laid by the civil rights and anti-war movements because it was this foundation that paved the way for Earth Day. When members of society band together, great things can happen.

Earth Day started off as a political demonstration, a way to bring attention to a seemingly unloved topic. However, it has evolved into much more than just a demonstration. “What began in 1970 as a protest movement has evolved into a global celebration of the environment and commitment to its protection.” Though Earth Day celebrations have never matched those of 1970, the spirit lives on through the annual observance of Earth Day and the spread of the idea to Earth Week and even Earth Hour celebrations. For all the success attributed to the Earth Day movement, the highest success was the foundation laid by the civil rights and anti-war movements because it was this foundation that paved the way for Earth Day. When members of society band together, great things can happen.

WORKS CITED

“A diverse coalition of supporters.” www.nelsonEarth Day .net. NA. Web. 12 Feb 11.

“A proposal reprinted across the country.” www.nelsonEarth Day .net. NA. Web. 12 Feb 11.

Bird, David. “Earth Day Plans Focus on City.” The New York Times 20 April 1970: 1. Print.

“Choosing not to be in Charge.” www.nelsonEarth Day .net. NA. Web. 12 Feb 11

DeBenedetti, Charles. An American Ordeal the Antiwar Movement of the Vietnam Era. New York: Syracouse University Press, 1990. Print.

“Earth Day Recollections: What It Was Like When The Movement Took Off.” www.epa.org. Whitaker, John. Web. 31 Oct. 2010.

“How the First Earth Day Came About.” www.envirolink.org. Nelson, Gaylord. WEB 31 Oct. 2010.

“Introduction: the Earth Day story and Gaylord Nelson.” www.nelsonEarth Day .net. NA. Web. 12 Feb 11.

King, Wayne. “Pollution Protests in April to be varied in Militance.” The New York Times 8 March 1970: 50. Print.

“Nelson’s Environmental Agenda.” www.nelsonEarth Day .net. NA. WEB. 13 Feb 2011.

“Rachel Carson: Pen Against Poison.” America.gov. n.p. WEB. 26 May 2008.

“The Iraq-Vietnam Comparison.” www.gallup.com. Carrol, Joseph. WEB 4 Feb 2011.

“The Living Tradition of Earth Day .” www.nelsonEarth Day .net. NA. WEB. 13 Feb 2011.

“The spirit of the first Earth Day .” www.epa.org. Lewis, Jack. WEB. 31 Oct 2010.

“What is Earth Day ?” www.america.gov. NA. WEB. 31 Jan 2011.

Williams, Juan. Eyes on the Prize Americas Civil Rights years 1954-1965.New York: Viking Penguin Inc., 1987. Print.