“A toast to the American Union -- to the forty-seven

states

and the soviet of Washington.”

Postmaster General, James Farley (1936)

Joanna

Goltz

The Soviet of Washington

Washington has long since buried its radical past in old books on dusty library

shelves or reduced it to a few pages in the middle school textbooks that I once

read from. Many people moved here in the late 1800s, brought here by the images

of a “New Eden” in pamphlets circulated in the eastern United States

(Radical 8-11).

These people came in search of a better life than they had known. In groups, they created towns where people could live collectively. Logging and the mining industries had brought many people here to work, and by the early 1900s, workers began to fight to create a better life where they were. During the Great Depression, lives were shattered by unemployment. In Washington, the unemployed organized to make the best life possible and organizations were formed to help lift the economy out of the depression. Throughout the period between the 1880s and the 1930s socialism and radical thought permeated through Washington, so much that in a visit in 1936, the Postmaster General, James Farley called the state “the soviet of Washington”.

Expansion of the Northwest

In the late 1800s real estate and other businesses tried to gather people from

all over the United States to move to the Pacific Northwest. They produced pamphlets

enticing people with descriptions of a Northwest with “vast and inexhaustible”

natural resources and a “land of exceptional promise” (The Pacific

Northwest 329 & Radical 8-9). One citizen of Boston noted that the pamphlets

“somehow left the impression that one could have a decent living in Oregon

and Washington simply by eating the gorgeous scenery” (Radical 7). It

was these ideas that led people streaming into the Pacific Northwest. Between

1850 and 1910, four million people immigrated to the west to extract the natural

resources that were apparently pouring from the land in the Northwest. Seattle’s

population grew over 1,000 percent during the 1800s (The Pacific Northwest 288

& Radical 15).

Some people believed that through their hard work, they would be able to live

virtuous lives and prosper unlike they had in the eastern part of the country.

They believed that working in the west was somehow better than working in the

east. (White 117)

The myths of endless resources and opportunities led many people to make Washington

their home, some for creating a perfect society and some for opportunities in

an unskilled labor force.

Utopian Experiments

Utopian colonies showed up in Washington in the mid-1800s. A Christian communist

group established the first colony on Willapa Bay in 1855. They had traveled

from Missouri under the leadership of Wilhelm Keil but soon had decided to move

on to the Willamette Valley to establish the Aurora Colony. The first modern

communitarian colony was the Puget Sound Cooperative Colony set up in Port Angeles

in 1887 by George Venable Smith. (The Pacific Northwest 353 & Utopias 11-12)

The goal was to establish “a separate community of collective industry,

means, utilities, public and private, and of persons under a single management

and responsibility for health, usefulness, individuality and security of each

and all” (Utopias 18).

The Pullman strike in 1894, which landed many working men and their leader Eugene

V. Debs in jail, led people to try to find a way of life better than that under

capitalistic greed. Out of this sprung the Brotherhood of the Cooperative Commonwealth

with plans to “colonize some state or state, so as to have a majority

therein of Socialists, then inaugurate Public Ownership of all means of production

and distribution as far as can be done within State lines”. With this

done, they would have influence nationally. (56-57) The Brotherhood sent Ed

Pelton to search for a perfect place to set up the ideal society. He found 280

acres for $2850 on the Puget Sound.

The surrounding area was densely forested and the closeness to the water provided the colony with a source of food. The soil was rich and good for farming. (O’Connor 4-5) It was on this land and one-decade after the establishment of the Puget Sound Cooperative Colony that Equality was founded. A constitution was written down and contained the goals of the colony:

(1) to educate the people in the principles of Socialism (2) to unite all Socialists

in on fraternal association; (3) to establish co-operative colonies and industries,

and so far as possible, concentrate these colonies and industries in one State

until said State is socialized. (Utopias 58)

Several other colonies formed over the next few years, scattered around Washington

State. None lasted longer than Home, which was considered more of an anarchist

colony than a socialist one. A visitor to Home wrote down what he had seen and

not seen at the colony:

…I found no church, no saloon, no gambling den, no butcher

shop, no house of prostitution, no one with a billy [club], …no extreme

poverty or almshouse, no prison or lock-up, no bitter criticism of their fellow

mortal—not being so very good themselves, … I found perfect freedom

of thought and action, and as a consequence a high degree of naturalness. …Plain

common sense people seemed to predominate. There are no rich and no poor, nor

does the dollar appear to be the main motive for activity. They seem to love

their books, and music and social intercourse more than the chase for the lucre.

(Washington State 185)

In 1922, the Seattle commune was established with a membership of eighty-seven

people. The members gave equipment, other supplies and a donation of $500 each.

This commune became the largest and most successful of the colonies and in the

1930s it became recognized as a collective farm. (Utopias 229)

Land in these colonies was commonly owned, although in Home, land was leased

and in Freeland, land was sold. Colonists set up cooperative stores and shared

in farming, lumbering, milling and other industries. Each colony had its own

newspaper.

The downfalls of these colonies were plentiful. They all had failed to achieve their original goals and maintain their existence. Some colonies evolved away from their communitarian ideals. The founders of the colonies did not have the managerial skills to run their experiments nor did they “understand human nature and psychology”. The governments of the colonies were too rigid to make room for any restructuring that needed to occur once the communal idea was put into practice. As a whole the colonies were not able to reform the country. For that, they would need to actively participate in politics. (Utopias 231-239)

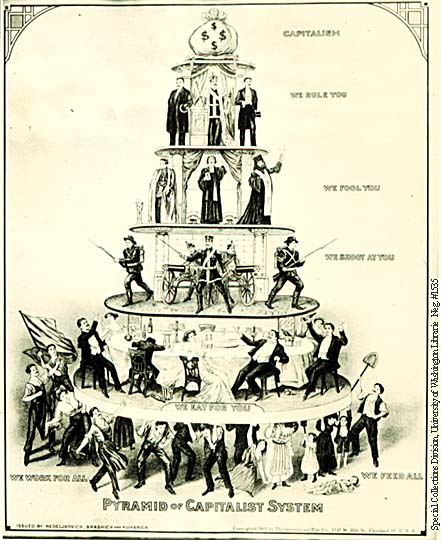

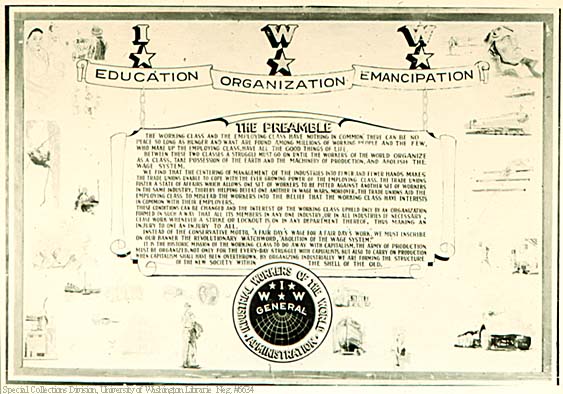

Labor Movement

Resource extraction was a major industry in Washington and it attracted many

people for unskilled labor. Conditions and circumstances of the work were nowhere

near desirable. Agencies in Spokane recruited workers for many jobs. The potential

worker arrived in Spokane and would have to pay a dollar to receive information

about a job. Many times they would arrive at a job site and discover that their

job had already been filled or did not exist and they would have to go back

to Spokane to pay another dollar to find another job. This incited the Industrial

Workers of the World (I.W.W. or Wobblies) to take action, which accumulated

into a fight for free speech in Spokane. (Findlay)

Once a worker got a real job and arrived at a logging camp, he would first see

what he was in for. The living conditions were horrendous. In the Report of

the Commission on Industrial Relations in 1916, J.G. Brown in response to being

asked to compare the treatment of horses and humans states:

…the beds are always made for the horses, the other fellows have to make their own beds, if they are made. Usually these men are tired out, and have no chance to, or care or desire to improve their conditions.

They just come in and sleep. Nearly all of these camps are infested with bedbugs, some of them have fleas, and some of them are lousy. One camp down on Grays Harbor – the men last summer went out and slept out doors in the woods, rather than tolerate the conditions in the bunkhouse. They would take their bed and go out and sleep on the ground in the woods. They did that for quite a period of time to get rid of the bed bugs. (The Pacific Northwest 332)

These conditions made it easy for unions to form and gain strength. The unions would play on the men’s prior belief that the west was a place to prosper and used the idea that the men did not want to be reduced to the status of an eastern worker by being treated so poorly by their bosses. (329)

It was in 1916 that “the bloodiest single episode of labor-related violence

in Pacific Northwest history” occurred in Everett (342). Everett was a

company town so the lumber company hired the police. The lumber company’s

deputies brutally beat several Wobblies and expelled them from town. This incited

over two hundred Wobblies, and at least a couple of Pinkerton spies, to come

to Everett on November 5th by way of a steam ship, the Verona.

Rumors had circulated that the Wobblies were out for revenge and planned to burn the city. Deputies and curious citizens were waiting at the dock with some deputies inside the surrounding buildings when the ship arrived. Before the passengers could leave the ship the sheriff approached and asked who their leader was. The response from the passengers was, “We’re all leaders”. At this point exactly what happened is up for debate. The I.W.W. claimed that there were no shots fired from the ship, whereas the deputies claimed that the first shots were fired from the Verona. Five Wobblies and two deputies died from gunshots, but many more union members died from jumping or falling overboard in an attempt to get away from the gunfire. At least twelve people died during this event and fifty more were wounded. Seventy-four I.W.W members went on trial in Seattle for first-degree murder several months later. The judge declared that the deputies that were killed were most likely killed by their own bullets ricocheting in the buildings. No member of the company’s deputies was ever charged in this incident. (See Clark 194-214, The Pacific Northwest 343 & Thompson 106-7)

In 1917, the lumber workers went on strike. The I.W.W. and the A.F.L. demanded

a minimum wage of $60 per month, sanitary bunkhouses, laundry and bathing facilities

nutritious food, and an eight-hour workday with no work on Sundays or holidays

(Thompson 115). When the lumber companies did not back down the unions decided

to “take the strike to work”. This meant that everyone would return

to their jobs but act as if their eight-hour workday was granted. At the end

of eight hours they went home. The workers continued to harass their employers

and restricted production by sabotage and “ca’ canny”. They

also would stand idle, play dumb and create accidents on the job. (Tyler 438)

However, the I.W.W. states that there was never any conviction of sabotage in

the union’s history (Thompson 81).

With a war going on, the United States needed lumber to build airplanes for

the Army. The lumber industry had convinced the government that their spruce

was the best wood for these planes and thus vital towards the success of the

war (The Pacific Northwest 357). The strike had come at a bad time for the government.

The Wobblies and the strikers were considered unpatriotic and thought of as

risking the lives of U.S. soldiers. Rumors soared around about the Wobblies

in cahoots with the Germans. The government finally stepped in and created the

Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen or the 4Ls. They worked directly with

the company bosses and received every one of the I.W.W.’s and the A.F.L.’s

demands. (Tyler 444)

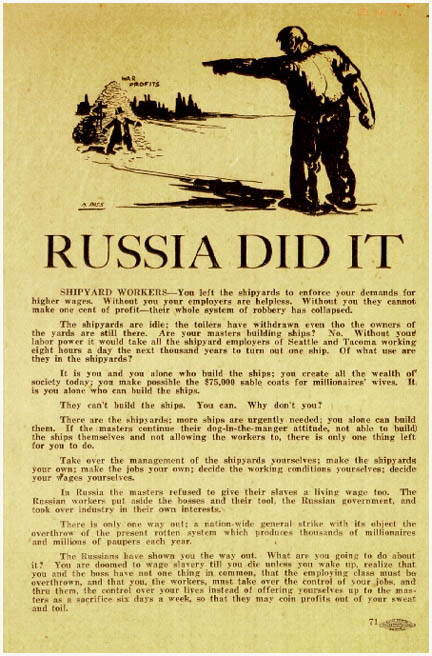

Nothing made it clearer that Washington was a radical state than the general

strike in Seattle in 1919. In the aftermath of the Great War, Seattle was still

struggling. The cost of living was high in the city and wages had not kept up

with inflation from the war. The northwest had long thought of themselves as

a colony that was being exploited by the big business in the east. (O’Connor

125-126)

In February of 1919 unions voted to use labor’s “most powerful weapon”, a general strike in solidarity with the shipyard workers. A committee was formed to plan out the strike. There were concerns of how people were to get food and what kinds of businesses should be kept in place to keep up public safety and health. On Tuesday the fourth of February an editorial written by Anna Louise Strong was published in the Union Record. It announced the strike would take place at 10:00am on that Thursday and told of what actions were to take place to insure public health and safety. Milk would be delivered for children and to hospitals, which would also receive their laundry service. The people would all be fed at low costs. Strong’s editorial stated that a strike probably would not be of much concern to the industries in the east for

“they could let the whole northwest go to pieces, as far as money alone was concerned” but that when it is shown that the workers are organizing to take care of the well-being of the city’s population “this will move them, for this looks too much like the taking over of power by the workers”. (132-133)

The Seattle Star urged the strikers to stop before the general strike occurred.

They claimed that the majority of the city was against the strike and likened

it to the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. The workers controlled the city. Milk

and hospital linen were being delivered, people were still getting food and

even prohibition was being enforced by the I.W.W. better than the government

had enforced it, but the shipyards in the East and in California remained open

and it was becoming apparent that “Seattle was expendable”.

Although the mayor told the workers to end the strike “or else”, it was the international unions who threatened to revoke the local charters that really had an impact on the decision to end the strike. (O’Connor 139-40) After shutting down the city for five working days, the strike ended on the eleventh. The Mayor of Seattle, Ole Hanson, had proclaimed that he single handedly ended the strike and stopped a Bolshevik revolution from taking over the city. The Seattle Daily Times stated that he was revered over the entire country for keeping the peace during the strike. His sentiments inflamed the fear that Communism had reached America. (The Pacific Northwest 360)

Unemployed Movement

In the midst of the Great Depression, the Unemployed Citizen’s League

was founded in 1931. Seattle claimed between 20,000 and 30,000 residents unemployed

at this time and their savings were running out, bringing hunger to the area.

The League became the first self-help organization of unemployed workers in

the United States. They advocated for the city and the county to employ people,

self-help, unemployment insurance and direct relief. The cities and counties

budgets were hurting, along with individuals. There was no money in their treasuries

to give any aid to the unemployed. Therefore the League turned to helping themselves.

They cut down “useless timber” to be used as firewood and were offered

food that had not been sold by farmers. They set up kitchens for canning and

preserving food and exchanged services amongst other unemployed workers for

supplies and other services. (O’Connor 218-220)

Politics

Throughout Washington’s history there was radicalism in politics. In 1897

Washington elected a governor from the Populist Party, John R. Rogers, and became

one of three states to ever elect a Populist governor. Part of the platform

of the Populist Party was the reduction of railroad and utility rates and an

issuance of a state income tax. Only a few of their goals were ever achieved,

but as the Populist Party was dying out, the Socialist Party of America was

formed in 1901. (Washington State 183-184)

Voters began to elect socialists to office, such as the mayors of Pasco and

Edmonds, and the city commissioner of Spokane. Members of the Washington State

legislature were even elected under the Socialist Party. When Eugene V. Debs

ran for President in 1912 he received 12 percent of the popular vote in Washington

State, which was over the national average (Utopias 238). By 1915, Washington

ranked second in the number of members of the Socialist Party per capita. (O’Connor

28)

A group within the Democratic Party, called the Washington Commonwealth Federation,

was formed in 1935 and campaigned for production to be for use, not for profit.

To bring some relief to the people hit by the Depression, the federation campaigned

for government ownership of banks, utilities and natural resources. In Revolutions

in Seattle O’Connor states that this “was a genuine people’s

movement, built by the hard work of the old-timers and the hopes of the newcomers

on the debris of a faltering economic system – perhaps the most genuine

people’s movement the United States had ever seen since its Revolutionary

days”(225). The federation claimed to have 30,000 members and led to the

Democratic national chairman and Postmaster General James Farley’s “toast

to the American Union”. (The Pacific Northwest 388-389 & Washington

State 213)

Conclusion

Radicalism comes when people are so desperate to make a better life that they

would do almost anything to make it possible. Washington was a land where a

better life seemed possible for many people and for some creating a socialist

community was the answer. For others who came here to work, found that their

labor was unappreciated and they fought for things people today take for granted.

The Seattle general strike made the nation fear of a revolution to overthrow

capitalism in the United States but it was the idea of government ownership

of utilities, natural resources and banks that made this state “the soviet

of Washington”.

Annotated Bibliography

Clark, Norman H. Mill Town: A Social History of Everett, Washington from Its

Earliest Beginnings on the Shores of Puget Sound to the Tragic and Infamous

Event Known as the Everett Massacre. University of Washington Press. Seattle,

WA. 1970.

This is a detailed history of the city of Everett, Washington. I used it primarily

for detailed information on the Everett Massacre.

“East Acclaims Seattle Mayor As Man of the Hour”. The Seattle Daily

Times. February 11, 1919.

A front page newspaper article that includes letters from people across the

country telling the mayor of their appreciation for him.

Findlay, John. History of Washington and the Pacific Northwest. [updated 1998;

cited August 25, 2003] Available from http://www.washington.edu/uwired/outreach/cspn/hstaa432/lesson_18/hstaa432_18.html

This is a lesson plan of a Pacific Northwest History class at the University

of Washington. This particular one follows the I.W.W. activities through the

early 1900s in Washington State and the events that brought about its downfall

in the region.

Le Warne, Charles Pierce. Utopias on Puget Sound 1885-1915. University of Washington

Press. Seattle, WA. 1975.

This book described the utopian settlements around Washington from the earliest

one in 1855. It describes the most noted five colonies that were set-up and

dissipated between 1885 and 1915.

Le Warne, Charles P. Washington State. University of Washington Press. Seattle,

WA. 1986.

This is a middle school text book that gives a general history of Washington

State. There were about two pages on the utopian colonies and information on

every subtopic that I have discussed in this paper.

O’Connor, Harvey. Revolution in Seattle. Left Bank Books. Seattle, WA.

1964.

A memoir and supplemented by several sources about the radical thought and action

in and around Seattle from the 1890s through the depression. This also was useful

in every section of this paper.

Schwantes, Carlos Arnaldo. The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History. University

of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, NE.1996.

A history of the Pacific Northwest which includes Washington, Idaho and Oregon.

This book includes a brief geography of the region and little detail on the

general strike and socialism. It does include many exerts on lumbering, utopias

and the I.W.W.

Schwantes, Carlos Arnaldo. Radical Heritage: Labor, Socialism, and Reform in

Washington and British Columbia, 1885-1917. University of Washington Press.

Seattle, WA. 1979.

This book went into the mythology of Washington State and British Columbia and

the socialist thought and actions that came to the area.

“Stop Before It’s Too Late”. The Seattle Star. Seattle, WA.

February 4, 1919.

A front page newspaper article urging the Seattle shipyard workers to not begin

the general strike.

Thompson, Fred & Murfin, Patrick. The I.W.W.: Its First Seventy Years (1905-1975).

Industrial Workers of the World. Chicago, IL. 1976.

This book describes the I.W.W.’s activities at the beginning of the organization.

It told of their activities around the country from the labor union’s

perspective. It was useful in the labor section of this paper especially for

the Everett Massacre.

Tyler, Robert L. “The United States Government as Union Organizer: the

Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen”. The Mississippi Valley Historical

Review. Vol. 47 Iss. 3. December 1960. 434-451.

An article describing the United States War Department’s involvement in

unionizing loggers to end a strike during the Great War.

White, Richard. Land Use, Environment and Social Change: The Shaping of Island

County, Washington. University of Washington Press. Seattle, WA. 1980.

I used a short chapter from this book that described the myths of coming to

the Northwest and what the reality was when they got here. It focused primarily

on farming and the idea that a virtuous life could be led in the country as

opposed to the city.