Kathleen Booth

What About Us?

Relief help, employment, vocational training, soup kitchens, promises of better

days to come and glimpses of hope were all that kept the fire burning in the

hearts of America’s youth, so wrongly caught up in the madness of the

world they were born to, in the 1930’s.

The “Great Depression” hit American youths like a ball of spiked

steel, it rolled across the country with all the force and destruction of

a battalion of war tanks, smashing and obliterating families in its all powerful

and deliberate path. The depression left tens of thousands of families so

torn apart that no patching, no government agency, or emergency program could

ever put them together again.

While the government went to work

developing programs (Works Progress Administration, Roosevelt Administration

19) to assist the millions of adults affected by the depression, few saw the

need to address the plight of the youths.

American youths between the ages

of 16 and 25, economically and socially challenged, often had no other choice

but to leave home to find employment. But with no marketable skills, no high

school diplomas, and no place to seek help and guidance, they often found

themselves, along with 54,000 others, living in transient camps moving from

state to state, working in filthy conditions clearing roadside ditches, sweeping

disgusting city streets, or working in unsafe and unsanitary conditions of

rural dumps. With yet another promise of employment these youths found themselves

being paid with less than nutritious food, and at the end of a long hard work

week all these people had to show for their efforts were parasites and sore

backs. Many of these youths would never find their way back home; they would

never again see parents, brothers, sisters, or grandparents. They would go

on to someday have families of their own and build futures, futures without

pasts.

Depression brought with it the

most heartbreaking, turbulent, and terrifying times that American youth would

ever experience. Young people had no idea what the government had done to

cause this awful transformation of their lives, but they did know that they

would have to hold fast to their belief in a once stable fair and pure democracy,

a democracy that they had hardly known before their world was turned up side

down. Poor or working class American youth had often been depicted as products

of their environment of poverty ignorance and a sorry upbringing. Before the

depression youths strived for what their parents had, jobs, homes, means of

being valuable members of a family and a community, When all that was gone,

there was nothing to look forward to, nothing to strive for, but staying alive

at all cost.

In June of 1935 the National Youth

Association was implemented as a program within the Works Progress Administration

to see the needs of poor American youth. Eleanor Roosevelt was very instrumental

in Persuading the President that the plight of America’s youth was a

cause to be dealt with as soon as possible. Social decline among youths was

accelerating. More then ever, young boys and men were being jailed for crimes

that rarely existed before the decline in the economic status of the country.

These youths were seen by many social groups and state government agencies

as idle troublemakers, who didn’t want to find work or try to get into

school; they were taking advantage of the currant situation to be bums. When

the problem was researched by a sociologist working for the New York Times

(Jonathan Mc Holland) he said that “The problem with Americas youth

is not the youth but the lack of support from America” his finding was

not in support of the general public. Eleanor Roosevelt took note of this

response and began working closely with the organizations leaders.

In 1935 Charles W. Taussig chairman

of the National Advisory Committee of the National Youth Administration thought

that the problems with youth during the depression were as follows:

“1. There are not jobs enough to take care of the youth

who need them and want them.

2. Our educational system is not adequate, in size or character, to prepare

multitudes of youth for the work opportunities that are available.

3. Nationally speaking, there is not equal opportunity for education systems.

There are not enough free schools to take care of the youth population, and

millions of youth and children are too poor to attend free schools and colleges

even where they exist.

4. There is a gap measured in years between the time a youth leaves school

and the time he finds a job. During this period society completely abandons

him. Most of our criminals are to be found in this social no-man’s land.”

These four points were the reason that the National Youth Administration was

created to work together to finding solutions for these problems. In June

1935, by national order of President Roosevelt, NYA was allocated $50,000,000

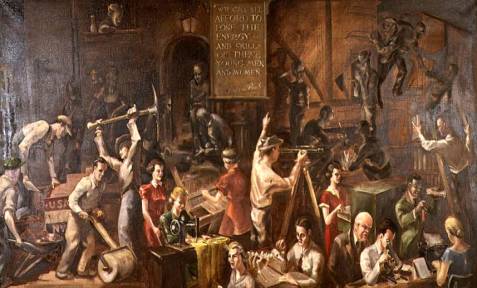

in relief funds. Roosevelt declared that, “we shall do something for

the Nation’s unemployed youth, because we can ill afford to lose the

skill and energy of these young men and women.”

Much of this funding was earmarked for families on relief, to aid youths in

furthering their educations. With this general funding, some 404,700 secondary,

college, and graduate students in urban areas would live out their dreams

of attaining a degree and go on to a long and prosperous career. This was

a great effort on the part of the NYA but still not enough to reach those

that were in the greatest need. The program fell short of meeting the needs

of rural youths on relief in getting them into school because the schools

simply did not exist. in southern states, rural counties did not offer black

communities schools at all, so much of this funding was also given to white

families not on relief but still could not afford to pay for schooling.

Vocational job training was offered

to youths in almost every aspect of job services work experience was not high

on the depression youths list of qualifications. In a majority of cases these

youths lied to gain the opportunity to learn a skill. It was either lie or

stay unemployed and un-skilled; most employers were looking for someone with

finely honed skills. It was fairly certain that the adult unemployed would

not be taking these jobs because they were looking for something that they

could support a large family of five or more. The majority of youths in southern

states gained work building schools; black youths were offered opportunities

to build their schools by turning old buildings into usable rooms to house

students. Vocational job training was offered in a variety of fields, including

carpentry, home economics, public service jobs, domestic training, seamstress,

building playgrounds. For about six months of their lives these youths trained

hard at becoming the best at their jobs, the job market was going to be tough

and so would they have to be.

Youths that were lucky enough to

stay in school also participated in work projects these jobs helped fund their

educations while they contributed to society, again these were youths who’s

families were not on relief but could not afford schooling.

In the rural areas of our nation, families suffered such hardships spent on

them by the current economic situation. Life was but a passing of days filled

with chores that made the difference in their very survival. Finding enough

food to feed a large family was a job, people often had to walk miles to a

neighbors or a small store to trade a few eggs for finer staples (flour, salt,

and cornmeal) that would stretch into bountiful meals. Children were sent

out to hunt for wild game and herbs, the forest they hunted in became their

playgrounds and learning to do this chore well was their education. The choice

to attend a real school and play on developed playgrounds was not theirs.

These possibilities were not even a thought in the minds of thousands of rural

youths.

NYA found it most challenging to

meet the needs of rural youths. In 1936 in an effort to meet theses needs

a new project was contrived, called NYA Resident Project. The project took

young men out of their rural homes and put them in low cost co-operative situations.

One such program started by Southwestern Louisiana Institute, a state engineering,

teachers, and agricultural college at Lafayette. The idea was that for $1.00

a month for room and $12.00 a month for food and living communally these young

men would work in the college partnered with regular college students in hopes

to learn a skill or trade. While not attending regular classes, groups of

young men rotated through the agricultural, animal husbandry, auto mechanics,

kitchen and ground keeping departments learning skills to someday use in their

own farming enterprises.

A

total of $40,000 was spent on building two dormitories, the young men were

paid $23.00 a month with $13.00 of these dollars went back to the school for

room and board. They took over maintenance of all buildings and grounds. No

monies were spent on curriculum or extra faculty. A curriculum that was specific

to the work that they were doing was all that was offered.

A

total of $40,000 was spent on building two dormitories, the young men were

paid $23.00 a month with $13.00 of these dollars went back to the school for

room and board. They took over maintenance of all buildings and grounds. No

monies were spent on curriculum or extra faculty. A curriculum that was specific

to the work that they were doing was all that was offered.

A similar program was offered to young women at the University of Louisianan, in home economics, a curriculum of meal planning, sewing and domestic work was offered, for those with good reading and writing skills there were typing and shorthand classes offered once a week.

The NYA may have had some good

ideas on how to meet the needs of America’s poor youth, but failed to

realize that once home with these upgraded skills, poor American youths still

did not have the education that could launch then into brighter economic future.

Rural farms were not big enterprises,

they supported one family at a time, and they sold or traded with local families

and markets. There were no mechanic shops or big farm equipment repair garages

to work in and animal husbandry was a natural phenomenon that was given very

little notice.

Once back home, finding a job to show off these newly acquired skills was not an easy task. There were not many hotels or huge mansions to clean and certainly no public or municipal offices needing skilled secretaries.

Many of the youth’s one in

particular, 22 year Arnold Craig stated in an interview with and NYA representative

following up on a few graduates of the resident Projects Program said that,

“he was not able to find a job anywhere.” He was trained to build

cabinets, but did not know how to read a blue print, “They never taught

us that part”. Poor American young people would return home with high

hopes and big dreams, dreams that they would be able to use their newly learned

skills to begin new lives, become independent and proud of their successes.

Instead they soon realized that their hopes would again be swallowed up by

the crushing wave of economic injustices that so ruled their lives. The NYA

resident program failed to educate young people on the possibilities of finding

jobs in the communities they came from, they failed to inform them that they

may have to reach outside their familiar surroundings and look into the world

for bigger possibilities.

Money spent on programs to job

train poor youths, could have been spent on building rural schools, and hiring

teachers to educate the young people that lived in theses communities. They

needed more then to just learn a trade that was not marketable at home, they

needed to participate as college students in classes with teachers that taught

more then life skills to improve a standard of living that was seen by many

middle class Americans as living in ignorance.

NYA failed to meet the educational needs of America’s poorest youth for many reasons, one being financial which always seems to be the main contributing factor, when a government agency fails. Dividing the NYA program among other government agencies (Federal Security Agency 1939 War Manpower Commission 1942) was another step in the failing direction. State agencies were also lacking in the strength to keep NYA programs available to poor youth’s. Funding was never enough and support from state representatives was little.

Then came another war World War

II, young men and women in training programs at the onset of WWII would go

on to work in private industry filling defense contract quotas, the rest of

America’s poor youth would stay poor: The NYA program was phased out

and America’s most prize possession was again forgotten.

Why has America left so many of

its citizens behind? The failure to provide quality educational and training

programs that meet the needs of Americas poor is going to be the failure of

America’s economical, social and political government.

Young people are the backbone of

our society, when this backbone becomes week from to much pressure it will

begin to erode away. In the process of this erosion, a landslide of social

and economic ruptures will come.

It can be seen so clearly in today’s

society as it was seen in the 1930’s, young people are restless, impatient

and angry because there is no place for them. They blame societies problems

on the past leaders blunders and mistakes as did the youth’s in the

1930’s

Young people just want a chance

to be educated, earn a living wage and be counted as a valuable informed citizen

of their country.

How can this problem of America’s youth be solved?

Annotated Bibliography

Lindley, Bety (Grimes) and Earnest Lindley. A New deal for Youth: the Story

of the National Youth Administration. New York: The Viking Press Publishers,

1938.

Lorwin, Lewis L. Youth Work Programs Problems and Policies. Washington D.C.:

The American Council on Education, 1941.

This book is a comprehensive attempt to present and discuss the major issues

which focus around the operation of a new social institution, and the public

youth work program.

Melvin, Bruce Lee and Elna Smith. Rural Youth: Their Situation and Prospects.

New York: DA CAPO Press, 1971

This book explains the New Deal for youth during the depression. It gives

a good over view of how the National Youth Administration helped fund education

programs and work projects for impoverished youths.

Reiman, Richard A. The New Deal and American Youth: Idea, ideals in a Depression

Decade. Athens, Georgia: Georgia press, 1992.

This book covers social conditions for 1933 to 1945 of the National Youth

Administration and its programs, progress. This book is about the intellectual

origins of the NYA the planning behind the creation.

Stanley, Payne L. Thirty Thousand Urban Youth Social Problems Series Number

6 of 6. Washington D.C: United States Printing Office, 1940.

This document will show how employment, wages, and other features of labor

market activity vary among young people of different ages.

Stouffer, Samual Andrew and Paul F. Lazarsfeld. Studies in the Social Aspects

of the Depression. New York: Arno Press, 1972.

The family in the depression economic pitfall of the United States how these

pitfalls affected the social climate of youths.