Memory Collected:

"Introducing Americans to America"

by Meg Herber

“We are the facilitators of our own creative evolution.”

-Bill Hicks

There’s a treasure lying in this country’s capitol and it’s not the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution, nor any other revered document. It has nothing to do with the Department of Treasury and it’s certainly not to be found in the Federal Reserve. The treasure I speak of is a collection of the nation’s memories – now known to many as history – memories of one of its most trying eras, the Great Depression. These memories are recorded in an extensive photo album gathered by means and subject both public and private. The images exist thanks to a group of individual photographers and their director who worked for the Historical Unit of the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Between 1935 and 1944, the FSA team dispersed across the country to document the state of the nation. They photographed land cracked with drought; fields eroded and unusable after years of poor agricultural planning and harsh weather; farms and towns enclosed in dust and flooded by nearby rivers; and dotted here and there along the roads on the outskirts of towns – refugee camps filled with the families of dispossessed farmers, laborers, and migrant workers. The photographers captured images of people standing in bread lines, employment lines, and bus lines; on the sides of city streets as well as country highways and railroad tracks. They documented the lives of the private citizens who made up the American public – at work and at home, playing, suffering, and many of the mundane moments in between. The resulting pictorial collection, housed in the Library of Congress, includes about 107,000 black-and-white photographic prints made from some 171,000 black-and-white film negatives and transparencies and 1,610 color transparencies . While some critics have argued that the photographs were mere propaganda used to push government programs , the collection is actually much, much more. Not only is it a landmark in the history of documentary photography , but as Roy Striker, the director of the photography program, described it – “the collection is one generation’s image of itself with the reality of its own time and place in history” . Now, almost 80 years later, it preserves part of the collective memory of the United States – memory of the nation’s people, their culture, and the conditions in which they lived.

The Photo Album

“The FSA was many things to many people. To some of its foes, it was a dangerous, radical, and un-American experiment in governmental intervention, paternalism, socialism, or communism […]; a plaything created for the diversion of utopian dreamers; an organized conspiracy to undermine the status quo in rural America […]. To friends of the [FSA], on the other hand, it was an heroic institution designed to secure social justice and political power for a neglected class of Americans; a pioneering effort to strike at the causes of chronic rural poverty; a unique and largely successful experiment in creative government” .

“To humanists, the [FSA] was a courageous effort to fulfill the aspirations for improvement of the human condition, through the harnessing of the power of optimism, knowledge, and man’s capacity to direct and control his own evolution. And to militant champions of racial equality, it was little more than a step in the right direction, a disappointing and faint-hearted effort to right ancient wrongs” .

Part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, the FSA began as the Resettlement Administration (RA) in 1935 and was headed by Roosevelt’s economic advisor, Rexford Tugwell. As a member of FDR’s team of advisors known as the Brain Trust, Tugwell organized the RA to address the mounting economic problems faced by America’s farmers and to restore life to the exhausted people . Under Tugwell’s direction, the RA/FSA would provide rehabilitation loans and resettlement opportunities to farmers impoverished by drought, soil erosion, and the effects of the Great Depression. But before he was one of the President’s advisors, Tugwell was a professor of economics at Columbia University where he met and mentored Roy Stryker.

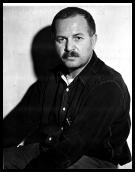

Roy Emerson Stryker was raised on a small farm near Montrose, Colorado, where he grew up with a great respect for the land and the people who toiled it – a respect instilled in him largely by his “Prairie Populist” father . The environment in which he grew up questioned the system as it existed and suggested that government could be used to improve people’s lives . After serving as a doughboy in World War I, Stryker studied and later taught economics at Columbia University. In December of 1935, he followed his mentor’s path to Washington, D.C. where Tugwell hired him as Chief of the Historical Section, in the Division of Information. According to Stryker, his job “was to collect documents and materials that might have some bearing on the history of the Farm Security Administration” and which would supply Tugwell’s field people “with tools to make the program clear [to local, state and federal officials]” .

Roy Emerson Stryker was raised on a small farm near Montrose, Colorado, where he grew up with a great respect for the land and the people who toiled it – a respect instilled in him largely by his “Prairie Populist” father . The environment in which he grew up questioned the system as it existed and suggested that government could be used to improve people’s lives . After serving as a doughboy in World War I, Stryker studied and later taught economics at Columbia University. In December of 1935, he followed his mentor’s path to Washington, D.C. where Tugwell hired him as Chief of the Historical Section, in the Division of Information. According to Stryker, his job “was to collect documents and materials that might have some bearing on the history of the Farm Security Administration” and which would supply Tugwell’s field people “with tools to make the program clear [to local, state and federal officials]” .

![]()

But Stryker ended up doing much more. From 1935 to 1943, with the help of the photographers armed with their cameras, his aim, he would say, was to “introduce Americans to America” . As he is described in the documentary, Documenting the Face of America by Jeanine Butler, the once assistant professor of economics became the unlikely instigator who would change the course of documentary photography by the sheer force of his personality . Stryker was ruthless in his efforts to get the FSA’s work seen by as many people as possible. He flooded newspapers and magazines such as Life, Focus, Survey Graphic, and US Camera with pictures, illustrated books free of charge, and organized public exhibitions. As Louise Rosskam, one of the FSA photographers recalls – “Roy was basically a teacher and he had really commenced the whole organization as a teacher, but on the other hand, he enjoyed a fight. […] If people were standing in his way, his greatest joy was to get them out of there” . For Stryker, it was all about feeding what he affectionately called “the file” .

“In the South, you had the tenant farmers’ problem, in the center, the Dustbowl problem, out in the west, the migrant farmer, and in the northeast, farm displacement – there really wasn’t a section of the country that you could afford to just ignore.”

– Roy Stryker

One of Stryker’s first and youngest recruits was Arthur Rothstein. Born in New York in 1915, and raised in the Bronx, the former Columbia student of Stryker’s first came to the FSA in the summer of 1935 to help organize the historical unit. He spent the first few weeks taking pictures of office space and official memoranda , but quickly became interested in trying his hand (and eye) out in the field. In 1936 – the same year as FDR’s reelection – Rothstein travelled to Pennington County, South Dakota on an assignment to document the persistent drought which had ravaged vast sections of the Great Plains. While driving along the road, he saw a steer scull lying in a patch of hummock grass . He stopped and snapped a picture of it and then he noticed a cracked, dried up pond. Placing the skull atop the cracks, Rothstein took a series of pictures which would be targeted by those in Washington who opposed Roosevelt and his New Deal programs and was criticized as blatant propaganda.

Another assignment took Rothstein to Oklahoma in 1936 in order to illustrate how the deadly combination of poor farming techniques and drought had devastated the land. In Cimarron County, Rothstein would take another iconic photograph, Fleeing a Dust Storm (Image 8) – a picture reproduced so often that the negative was worn out years ago . The image of a farmer and his son walking across their field about to be covered in dust also raised accusations of propaganda , never mind that the farmer and his situation were as real as the dust cloud looming in the horizon.

Another assignment took Rothstein to Oklahoma in 1936 in order to illustrate how the deadly combination of poor farming techniques and drought had devastated the land. In Cimarron County, Rothstein would take another iconic photograph, Fleeing a Dust Storm (Image 8) – a picture reproduced so often that the negative was worn out years ago . The image of a farmer and his son walking across their field about to be covered in dust also raised accusations of propaganda , never mind that the farmer and his situation were as real as the dust cloud looming in the horizon.

![]pis](meg_clip_clip_image004_0001.jpg)

In February 1937, Rothstein was in north-central Alabama photographing Birmingham's steel industry and some nearby resettlement housing projects when he received new instructions from Stryker to document a tenant community by the name of Gee’s Bend – which was about thirty miles southwest of Selma, Alabama – and the 700 or so African Americans who lived in what Stryker called “the most primitive set-up [he] had ever heard of” . While Rothstein showed the back-breaking work of cultivation and harvest in some of his pictures, he also attempted to show the dignity in which the people of Gee’s Bend lived their lives. The residents do not merely inhabit the substandard housing and living conditions, but engage in activities of home, school, church, labor, play – in short, their community.

Walker Evans was another photographer recruited by Stryker during the first year of the program. Evans already had a reputation as a documentary photographer for his work illustrating a book which exposed the evils of Cuba’s Machado regime and photographs of African sculpture for the Museum of Modern Art . He also did some part-time work for the Department of Interior, where Stryker was first introduced to his work. He was very influenced by Evans’ ideas regarding the systematic documentation of what he called the quintessential American material culture. According to Evans, he “called for images that would be a pure record – not propaganda” , composing lists of potential subjects which resembled the shooting scripts Stryker would later assign to the rest of the team. While Evans was one of the first photographers hired by Stryker, he was also the first fired. Though Stryker gave the photographers some creative autonomy, he was still a bureaucrat who demanded detailed accounts of their expenses and whereabouts. Evans’ tendency to run off without providing much of either was the cause of a good deal of friction between photographer and director.

Walker Evans was another photographer recruited by Stryker during the first year of the program. Evans already had a reputation as a documentary photographer for his work illustrating a book which exposed the evils of Cuba’s Machado regime and photographs of African sculpture for the Museum of Modern Art . He also did some part-time work for the Department of Interior, where Stryker was first introduced to his work. He was very influenced by Evans’ ideas regarding the systematic documentation of what he called the quintessential American material culture. According to Evans, he “called for images that would be a pure record – not propaganda” , composing lists of potential subjects which resembled the shooting scripts Stryker would later assign to the rest of the team. While Evans was one of the first photographers hired by Stryker, he was also the first fired. Though Stryker gave the photographers some creative autonomy, he was still a bureaucrat who demanded detailed accounts of their expenses and whereabouts. Evans’ tendency to run off without providing much of either was the cause of a good deal of friction between photographer and director.

In a 1974 interview, Evans admits that he was attracted to the South for its romanticism, history, and heritage . During the eighteen months he worked for the FSA, Evans took photographs in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Yet he is best known for the work he did with writer, James Agee in the summer of 1936. Evans and Agee went to Hale County, Alabama on an assignment for Fortune magazine to explore the lives of three tenant families. Though the magazine opted not to run the story, Evan’s stark photographs and Agee’s detailed narrative were published in the book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Many of the photographs Evans made during this time were later described by art critic, John Szarkowski as "poetic uses of bare-faced facts, facts presented with such fastidious reserve that the quality of the picture seemed identical to that of the subject” .

In a 1974 interview, Evans admits that he was attracted to the South for its romanticism, history, and heritage . During the eighteen months he worked for the FSA, Evans took photographs in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama, Arkansas, and Tennessee. Yet he is best known for the work he did with writer, James Agee in the summer of 1936. Evans and Agee went to Hale County, Alabama on an assignment for Fortune magazine to explore the lives of three tenant families. Though the magazine opted not to run the story, Evan’s stark photographs and Agee’s detailed narrative were published in the book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Many of the photographs Evans made during this time were later described by art critic, John Szarkowski as "poetic uses of bare-faced facts, facts presented with such fastidious reserve that the quality of the picture seemed identical to that of the subject” .

While Evans was known for keeping a particular kind of distance between himself and the people he photographed, which he felt was necessary in order to keep his records from becoming too sentimental and maudlin, he was also quite aware of it being a moment in time that would not come again . As he once remarked to a friend, “what I was seeing through the camera lens when I was down South, was something that was so exciting, it almost would make you go mad” .

During the Depression, up to six thousand migrants arrived in California from the Midwest every month, driven there by unemployment, drought, and the loss of farm tenancy. Dorothea Lange was already there documenting migrant farm workers in the Imperial Valley for the California State Emergency Relief Administration when Stryker invited her to join the FSA in 1935 . From then until 1940, Lange would work tirelessly to document the plight of sharecroppers, immigrant and migrant workers, and displaced farm families, following them and the harvest seasons through central California and Oregon, and into Washington’s Yakima Valley. Often accompanied by her husband, Paul Taylor, an associate professor of economics at UC Berkeley, Lange drove up and down the West Coast and to Washington, D.C.; to the South – Arkansas, Mississippi, and Alabama; and to the Dust Bowl – Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma . Everywhere she went she was constantly talking to people and taking pictures, living a hard, exhausting life which she thrived on.

During the Depression, up to six thousand migrants arrived in California from the Midwest every month, driven there by unemployment, drought, and the loss of farm tenancy. Dorothea Lange was already there documenting migrant farm workers in the Imperial Valley for the California State Emergency Relief Administration when Stryker invited her to join the FSA in 1935 . From then until 1940, Lange would work tirelessly to document the plight of sharecroppers, immigrant and migrant workers, and displaced farm families, following them and the harvest seasons through central California and Oregon, and into Washington’s Yakima Valley. Often accompanied by her husband, Paul Taylor, an associate professor of economics at UC Berkeley, Lange drove up and down the West Coast and to Washington, D.C.; to the South – Arkansas, Mississippi, and Alabama; and to the Dust Bowl – Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma . Everywhere she went she was constantly talking to people and taking pictures, living a hard, exhausting life which she thrived on.

In 1936, after her own long day in the field, Lange was driving down the road when out of the corner of her eye she saw a crudely made sign pointing the way to a pea-pickers camp. She almost didn’t stop. But after about twenty miles and a long internal dialogue convincing herself to turn around , she went back and found a woman and her children stranded alone at the edge of the camp. While talking to Florence Thompson and her children, Lange shot her iconic photograph, Migrant Mother (Image 10) – another picture subject to accusations of propaganda. Though the photograph did actually persuade legislators to create the first federally funded housing program for migrant workers entering California, by the time help did show Thompson and her family had already moved on.

In 1936, after her own long day in the field, Lange was driving down the road when out of the corner of her eye she saw a crudely made sign pointing the way to a pea-pickers camp. She almost didn’t stop. But after about twenty miles and a long internal dialogue convincing herself to turn around , she went back and found a woman and her children stranded alone at the edge of the camp. While talking to Florence Thompson and her children, Lange shot her iconic photograph, Migrant Mother (Image 10) – another picture subject to accusations of propaganda. Though the photograph did actually persuade legislators to create the first federally funded housing program for migrant workers entering California, by the time help did show Thompson and her family had already moved on.

Lange’s photographs for the FSA were intended to bolster support for the establishment of livable migrant camps in order to aid those wondering the countryside in search of work. But with the onset of WWII, the FSA was transferred – lock, stock, and barrel – to the Office of War Information (OWI), and the motivation behind the assignments shifted. In 1942, Lange was assigned to document what the government wanted to portray as the “fair treatment” of some 120,000 Japanese-Americans rounded-up and shipped off to internment camps. Soon after, she resigned.

Ben Shahn worked for the FSA as an artist, designer, and photographer from 1935 to 1938. Most biographers and bibliographers focus on Shahn’s achievements as a painter, muralist, graphic artist, and illustrator, but in those first years of the FSA program, he would make two important contributions to the newly formed Historical unit – the photographs he took which made up about one-third of the early collection and his council to Roy Stryker which helped the director clarify “the mission”. When Shahn joined the FSA, most of the images in Stryker’s file focused on the dry, eroded soil. Shahn informed him that while those images where fine, they wouldn’t sell anything without showing the people who lived, worked, and suffered on that land .

Ben Shahn worked for the FSA as an artist, designer, and photographer from 1935 to 1938. Most biographers and bibliographers focus on Shahn’s achievements as a painter, muralist, graphic artist, and illustrator, but in those first years of the FSA program, he would make two important contributions to the newly formed Historical unit – the photographs he took which made up about one-third of the early collection and his council to Roy Stryker which helped the director clarify “the mission”. When Shahn joined the FSA, most of the images in Stryker’s file focused on the dry, eroded soil. Shahn informed him that while those images where fine, they wouldn’t sell anything without showing the people who lived, worked, and suffered on that land .

Born in Lithuania in 1989, Shahn and his family immigrated to New York when he was six. Shahn brought a different spin to the situation than Walker Evans, who he shared a studio with in Greenwich Village at the time. According to biographer, Margaret Weiss, Shahn’s nature, manner and approach to taking pictures was such that he could reach out and into the people he photographed . As Shahn humbly explained –

Born in Lithuania in 1989, Shahn and his family immigrated to New York when he was six. Shahn brought a different spin to the situation than Walker Evans, who he shared a studio with in Greenwich Village at the time. According to biographer, Margaret Weiss, Shahn’s nature, manner and approach to taking pictures was such that he could reach out and into the people he photographed . As Shahn humbly explained –

“I talk to them… I like them. I like people – and maybe they knew I liked them.”

Shahn took over six thousand photographs in the South and Mid-West, often travelling with his wife, Bernarda. She recounts that “all the time that Ben was photographing, [quietly gathering statistics on how people were living], he not only saw the grimness of things he was photographing, he also saw the humor of it… he saw the pathos of it” . According to Weiss, the pictures he took convey that he related to the people and knew something about what was going on in their minds and troubled lives. The images project a sense of place, but not necessarily any particular locale – scenes in a town or in the country – yet all are part of a period which reflected an economic and social attitude born of hard times.

According to Shahn, his vision of the FSA’s photography program was very simple and direct – “We tried to present the ordinary in an extraordinary manner. But that’s a paradox, because the only thing extraordinary about it was that it was so ordinary. Nobody had ever done it before, deliberately. Now it’s called documentary… We just took pictures that cried out to be taken”. He believed that “it is the mission of art to remind man he is human” .

According to Shahn, his vision of the FSA’s photography program was very simple and direct – “We tried to present the ordinary in an extraordinary manner. But that’s a paradox, because the only thing extraordinary about it was that it was so ordinary. Nobody had ever done it before, deliberately. Now it’s called documentary… We just took pictures that cried out to be taken”. He believed that “it is the mission of art to remind man he is human” .

Marion Post Wolcott began working for the FSA in September of 1938. According to a biography written by her daughter, Linda, her mother would “spend the next three and a half years taking pictures in New England, Kentucky, North Carolina, Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi. [During which time], Wolcott survived illness, bad weather, rattlesnakes, skepticism about a woman traveling alone and the sometimes hostile reaction of her subjects in order to fulfill her assignments from the FSA” . According to another biographer, Sally Stein, Wolcott had been characterized as the atypical photographer hired by Stryker – a romantic “city girl” working in a predominately male group of seasoned social observers . As Jack Hurley, a historian of the New Deal and Depression Era, describes her, “Wolcott had a very serious disability – she was a beautiful young woman and it made it hard for [Stryker] and a lot of people to take her seriously. [Although Stryker would use her largely as a public relations resource], she was a marvelous photographer” . She also had, in both her manner and her photography, rebellious and fiercely critical tendencies which surfaced in countless letters to Stryker in which she would momentarily rail against the “moralism” of social workers, the bungling ineptitude of FSA regional bureaucrats and the complacency of the middle class .

Marion Post Wolcott began working for the FSA in September of 1938. According to a biography written by her daughter, Linda, her mother would “spend the next three and a half years taking pictures in New England, Kentucky, North Carolina, Florida, Louisiana and Mississippi. [During which time], Wolcott survived illness, bad weather, rattlesnakes, skepticism about a woman traveling alone and the sometimes hostile reaction of her subjects in order to fulfill her assignments from the FSA” . According to another biographer, Sally Stein, Wolcott had been characterized as the atypical photographer hired by Stryker – a romantic “city girl” working in a predominately male group of seasoned social observers . As Jack Hurley, a historian of the New Deal and Depression Era, describes her, “Wolcott had a very serious disability – she was a beautiful young woman and it made it hard for [Stryker] and a lot of people to take her seriously. [Although Stryker would use her largely as a public relations resource], she was a marvelous photographer” . She also had, in both her manner and her photography, rebellious and fiercely critical tendencies which surfaced in countless letters to Stryker in which she would momentarily rail against the “moralism” of social workers, the bungling ineptitude of FSA regional bureaucrats and the complacency of the middle class .

While many of the published selections from her FSA work concentrate on a limited group of images depicting fertile farms and quiet New England towns, many of her photographs show the recurrent concern with the difficult and persistently divisive issues of American class and race. Far from reducing these issues to rhetoric that can categorically reduce the nature of people and their experiences, Wolcott’s photographs bear profoundly on the seemingly smallest, mundane, and constant features of daily life. The picture to the left does not explicitly refer to racism – no rights are being obviously deprived – yet the racial tension is evident in the way the two black men move quickly in single file, cutting a wide arc so as to avoid close contact with either the white woman walking in the opposite direction or the stationary white man who seems to stare, perhaps suspiciously, at the photographer across the street.

While many of the published selections from her FSA work concentrate on a limited group of images depicting fertile farms and quiet New England towns, many of her photographs show the recurrent concern with the difficult and persistently divisive issues of American class and race. Far from reducing these issues to rhetoric that can categorically reduce the nature of people and their experiences, Wolcott’s photographs bear profoundly on the seemingly smallest, mundane, and constant features of daily life. The picture to the left does not explicitly refer to racism – no rights are being obviously deprived – yet the racial tension is evident in the way the two black men move quickly in single file, cutting a wide arc so as to avoid close contact with either the white woman walking in the opposite direction or the stationary white man who seems to stare, perhaps suspiciously, at the photographer across the street.

As Stein points out, though the New Deal included legislation which attempted to improve the conditions of the lesser known farm laborers, one group (among others) left unprotected was domestic workers. Nearly two million women were thus employed during the Depression, and of them, nearly half were African American . Faced with fewer job options, black domestics as a rule worked longer hours for lower wages. Among the messages Wolcott conveys in the picture shown to the right is the suggestion of a surplus of black women concentrated in domestic work and living in the margins of society – easily replaced and therefore easily exploited – and their assumption that their own presentation to the camera is of less importance than that of the child in the presence of an unfamiliar white photographer.

Gordon Parks was one of the last photographers to join the FSA. He was in Chicago photographing the poverty of African Americans living in the city’s south side at the same time members of the FSA team were there documenting the Great Migration of thousands of displaced southern Black Americans into the northern cities. In 1942, he travelled to Washington, DC, where he first met Stryker.

Gordon Parks was one of the last photographers to join the FSA. He was in Chicago photographing the poverty of African Americans living in the city’s south side at the same time members of the FSA team were there documenting the Great Migration of thousands of displaced southern Black Americans into the northern cities. In 1942, he travelled to Washington, DC, where he first met Stryker.

In an interview included in Butler’s documentary , Parks recalls that at their first meeting, Stryker asked him point blank what he knew about Washington, DC. Parks replied that he thought “it should be the seat of democracy”, that if there was anyplace where people were treated justly, it would be the nation’s capitol. According to Parks, Stryker just looked at him, smiled and sent him out on an assignment to get some lunch in a restaurant across the street and then review a film playing in a nearby theater. That “simple assignment” would enlighten Parks to the optimistic naiveté of his earlier statement as he recalls that what he experienced there was "discrimination and bigotry worse than any place [he] had yet seen”. When Parks returned to the office, Stryker asked him, “Well, how did it go?” To which Parks replied, “I think you know how it went.” Stryker said, “Yeah, I know how it went… What are you going to do about it?” Parks answered that he didn’t know. Then Stryker asked him, “Well, what did you bring that camera down here for?”

In an interview included in Butler’s documentary , Parks recalls that at their first meeting, Stryker asked him point blank what he knew about Washington, DC. Parks replied that he thought “it should be the seat of democracy”, that if there was anyplace where people were treated justly, it would be the nation’s capitol. According to Parks, Stryker just looked at him, smiled and sent him out on an assignment to get some lunch in a restaurant across the street and then review a film playing in a nearby theater. That “simple assignment” would enlighten Parks to the optimistic naiveté of his earlier statement as he recalls that what he experienced there was "discrimination and bigotry worse than any place [he] had yet seen”. When Parks returned to the office, Stryker asked him, “Well, how did it go?” To which Parks replied, “I think you know how it went.” Stryker said, “Yeah, I know how it went… What are you going to do about it?” Parks answered that he didn’t know. Then Stryker asked him, “Well, what did you bring that camera down here for?”

One night, Stryker pointed out a cleaning lady working in one of the government offices. Ella Watson, an African American woman with the same education and accomplishments as the white women who served in higher capacity there , was the subject of one of Park’s first essays. His portrait of Watson entitled American Gothic (Image 11), is as much an icon of his career as it is of the FSA/OWI collection. It is also one of the most unapologetic indictments of American government and culture to come out of the FSA photography program.

One night, Stryker pointed out a cleaning lady working in one of the government offices. Ella Watson, an African American woman with the same education and accomplishments as the white women who served in higher capacity there , was the subject of one of Park’s first essays. His portrait of Watson entitled American Gothic (Image 11), is as much an icon of his career as it is of the FSA/OWI collection. It is also one of the most unapologetic indictments of American government and culture to come out of the FSA photography program.

After that first experience in DC, Parks was determined to show the rest of the world what the supposedly greatest capitol in the world was really like by photographing scenes of injustice and portraits of bigots. But one of the greatest lessons he learned from Stryker, he recalls, is the effectiveness of photographing the victims instead of perpetrators – since bigots can have a way of looking like everyone else – and the importance of the words which accompany the images. For two years, Parks would use the camera as his choice of weapons against the evils of American society. But in 1944, Park’s left the FSA/OWI to fight on his own after the government stopped him from photographing the first black fighter pilot squadron to fly in WWII.

Conclusion

Roosevelt’s New Deal and the programs like the FSA, while they did bring some relief to some desperate people during the Great Depression, did not solve the problems of poverty, race, and class which exist in the United States. In the scope of the country’s history during the twentieth century, the FSA photographs barely whisper the social and economical state of its people during only one decade. But the thousands of photographs collected in this national photo album provide as honest an image of the American public as any scrapbook containing the memories of a single family. As for the question of the photographs being propaganda – as photographer Louise Rosskam admits in her interview with Butler,

“This file was definitely propagandistic, there’s no question about it. But when you really looked at it, you couldn’t stand it – you had to do something. So propaganda, to me, means a call to do something” .

And isn’t that what propaganda is, the use of information to motivate particular thought and action? Propaganda isn’t false or maliciously manipulative in and of itself. It is defined by the motivation behind it. However many words a picture may speak – listen for that buzzing of truth. Does it escape into ideology or reinforce reality? Many of the images captured by the photographers had nothing to do with selling the program. They were images of people living and dealing with their own realities (not too dissimilar from pictures found on many a Facebook page today). Dorothea Lange’s experience photographing the treatment of Japanese Americans after the attack on Pearl Harbor marks a key difference in motivational information. After the program was taken over by the OWI, when the government encouraged support for the war instead of helping the public, the motivation of the photographers was no longer there. For Stryker, his motivation became the preservation of the file and protecting it from those within the federal bureaus and on Capitol Hill who wanted the FSA to disappear without a trace. As Stryker would write in a letter to the White House –

This record is in one piece. The oldest pictures in it have been as valuable as the most recent to the OWI. At present, this coverage conceived and produced as an unbroken continuity, is in danger of being dispersed. Such dismemberment would be fatal, for this is a live and active record. Out of America at peace, grew the strength of America at war. This soil is the same soil and the people are the same people.

It is possible to preserve the record intact and still make it available to the OWI and other war agencies for current use. This can be accomplished by transferring the custody of the file to the Library of Congress.

Works Cited

Baldwin, Sidney. Poverty and Politics: The Rise and Decline of the Farm Security Administration. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968. Print.

Butler, Jeanine I, Alastair Reilly, Catherine L. Butler, and Julian Bond. Documenting the Face of America: Roy Stryker and the FSA/OWI Photographers. Columbia, S.C: SCETV, 2007.

Curtis, James. Mind's Eye, Mind's Truth: FSA Photography Reconsidered. American civilization. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989. Print.

Doud, Richard. Oral history interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965. 17 Oct. 1963 Session. Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution. 16 Jan. 2011 <http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-roy-emerson-stryker-12480#october_17,_1963_session>

“Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.” Prints and Photograph Online Catalogue. The Library of Congress. 5 Feb. 2011. Path: Background and Scope. <http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/fsa/background.html>.

Ferris, William R., Walker Evans, and Eudora Welty. Images of the South: Visits with Eudora Welty and Walker Evans. Southern folklore reports, no. 1. Memphis: Center for Southern Folklore, 1977. Print.

The Photographers: Roy E Stryker (1893-1975). Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh Online. 2011. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. 23 Feb. 2011 <http://www.clpgh.org/exhibit/ photog14.html>

Shahn, Ben, and Margaret R. Weiss. Ben Shahn, Photographer; an Album from the Thirties. New York: Da Capo Press, 1973. Print.

Wolcott-Moore, Linda, eds. The Photography of Marion Post Wolcott. 1999. 16 Feb. 2011 <http://people.virginia.edu/~ds8s/mpw/mpw-top.html#COM>

Wolcott, Marion P., and Sally Stein. Marion Post Wolcott, Fsa Photographs. Carmel, Calif.: Friends of Photography, 1983. Print.

Images Cited

http://www.amazon.com/Choice-Weapons-Gordon-Parks/dp/0873512022