Vanport, Manly Maben (via freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com)

Working Utopia

by Charlotte Webb

The myth of a “Worker’s Utopia” in Portland, Oregon persists

“If you were coming to Portland to work in the shipyards and you signed up,” says E. Shelton Hill,” you not only got your transportation here, they gave you the street address of the house where you were going to live.” Hill served as Tenant Relations Advisor within the Vancouver, WA housing authority in 1945. He went on to hold the position of Director of Industrial Relations for the Portland, OR Urban league in 1947, providing him an intimate knowledge of the housing restrictions and conditions in the Pacific Northwest of that era. The shipyard he references is the Kaiser shipyard, whose many workers called Vanport City home. Designed as a temporary housing community, Vanport City was constructed especially for the families of Pacific Northwest-based defense workers during World War II. Completed in 1943, it stood a mere five years.

Vanport, Manly Maben (via freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com)

Due to the brevity of its existence, few sources detail the daily lives of Vanport's inhabitants. For perhaps the most detailed work, sociologist Hope Lunin Boyle compiled a sketch of the community via questionnaires and interviews, but elected to focus solely on the observations of white tenants. Many other published accounts are at odds with each other, the views they promote veering toward extremes; for example, the Housing Authority of Portland (HAP) is nearly always depicted as corrosive and underhanded or benevolently community-minded.

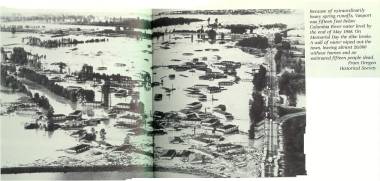

That Vanport City was all but consumed by a flood also explains the dearth of information pertaining to the city’s destruction: most records of daily life were destroyed when the dikes broke, the documents washed away with the lives they described.

Still, the memory of Vanport persists. And for the most part, the city’s inhabitants remained in Portland. Lasting implications of community accord--no matter one’s race or station--have become Vanport’s most oft-promoted attribute.

I first heard about Vanport quite by accident, years after I’d left Portland. Unable to sleep and channel surfing, I happened upon a public broadcasting special recounting the experiences of minorities in Oregon before the Civil Rights movement. Amidst the tension and contempt in Portland, Vanport City stood out as a bright spot of acceptance. Former residents talked of integrated schools and community dances, while minorities who lived in Portland-at-large recalled taunts and jeers. The Portland school district would not hire black teachers, yet Vanport had two. How were these opposing social climates able to exist within such close proximity? It seemed a question worth exploring.

Start to finish, Vanport’s construction took less than a year. Yet despite its temporal existence and the rush to complete it, much attention was paid to its development; indeed, the monies allotted toward its construction totaled roughly $26,000,000. The apartments were designed in a uniform fashion, a series of boxy complexes. As described in Vanport, Manly Maben’s seminal work on the community:

Each building contained 14 apartments, and every four of them were linked to a central utility building by covered passageway. There were two other types of apartment buildings, but they were negligible in number (17 in all).

Vanport Residences, 1947; catalog no. OrHi78694 (via ohs.org)

Housing most Vanport families, East Vanport connected via underpass to the single dwellers and the greater Vanport community.

Much was made of landscaping--quite a lot of money was allotted to the laying of grass and importing of shrubbery--though it seems to have made little improvement. As reported in Elements of Tenant Instability in a War Housing Project, muddy conditions were listed as a chief complaint within the community. As they were published a mere two years before Vanport City was destroyed by a flood, such complaints of mud--as well as Elements authors Charlotte Kilbourn and Margaret Lantis’ remarks on the subject--seem ominous.

A more immediate threat within the city seems to have been fire. Residents complained of stove-tops overheating, sometimes melting the Bakelite knobs. That all buildings were wood must have added to rising concerns. According to Maben, Vanport experienced some 217 fires between May 1943 and May 1945. Many of these developed in the utility buildings, particularly those housing the furnaces.

The Housing Authority of Portland (HAP) did little to allay fears.

Recent writings make clear that the concerns of the HAP were chiefly financial. Fires lead to fire damage, yet modifications to Vanport apartments were strictly prohibited and subject to fines. The vague disallowment of alterations--”not allowed” under any circumstances--did not take into account the necessity of such after damage occurred.

Many other fines applied to Vanport residents. Ice trays and the need to empty them frequently, lest they lead to water damage, was singled out in the Resident Handbook.

There were also complaints of vermin within the apartments. “By July 1944,” writes Maben, “complaints of bedbugs averaged almost 900 a month and of cockroaches, over 1,500.” By 1945, “ A heavy DDT spray of eight apartments (one pint per apartment) yielded excellent results with no call-backs.” As Vanport had such a high turnover-rate, we cannot know what effects the DDT spray elicited.

That Vanport residents put up with such conditions is a testament to their need, as well as the lack of available residences within Portland, OR and its outlying boroughs. There were roughly 42,000 people living in Vanport by mid 1944, though the constant flux of in-migrants moving through the community makes it difficult to present an accurate number.

In general the population is composed of young people. 63% are under twenty-six years of age, people interested and able to work in the shipyards and in the defense industries. The over-all sex composition shows a preponderance of females, and the racial composition a preponderance of Whites with approximately 2.5 Whites per Negro.

The transient nature of Vanporters was as much the result of poor living conditions as it was their economic background. Most, it seems, had been living below the poverty line prior to arriving in Oregon. Class prejudices fed the stigma against Vanport, its citizens were denigrated by the public at large. Some were even refused service in Portland shops. Rumors of fights and other transgressions preceded them.

Vanport schools covered grades K through 8, so Vanport teenagers were bussed into Portland to attend city high schools. In her 1945 thesis, Lillian Kessler claims that these students were often ostracized.

When the Vanport bus drew up before the school the boys and girls were jeered and ridiculed. The situation was so disturbing to some that they would get off of the bus several blocks before the school and then take a circuitous route to arrive at the building.

For some Vanport citizens there was another cause for prejudice: they were black.

The exclusion, persecution and isolation of African Americans residents(sic) has been a defining aspect of the history of race relations in Oregon dating back to its earliest days as an unincorporated territory of the United States. The actions of white citizens councils, the codification of racially discriminatory practices by local governing bodies, and the threat of the mob, militia, and police force together engendered a formidable repressive atmosphere for black Oregonians from the middle of the nineteenth century through World War II. (Tsalbrin 11)

Despite persisting views of Vanport as a sort-of ethnically diverse idyll, there is very little to indicate this was the case. In fact, interactions between whites and blacks within Vanport was one of the top complaints among its residents. Within Vanport in 1946, 6000 residents were black. Yet in 1940, just a few year prior to Vanport’s construction, black citizens in Portland totaled just under 1800. In the film Local Color, black Portlanders recall being barred from restaurants during the war years, signs propped up in windows alerting them that they were not welcome owing to their race. And the Northwest was not known for its racial tolerance. So why the pervasive view of racial harmony within Vanport City?

In “Rising Anxieties, Rising Waters,” Sarah Tsalbrin points out the HAP published reports of racial harmony within Vanport City as a matter of public policy. Somewhat ironically, as Tsalbrin writes:

Where one might have expected that an exchange of hostilities between white Southern migrants and blacks would have been common occurrence within multi-racial Vanport, it was rather positive social exchanges between “the races” which appear to have most deeply troubled police.

Given the small number of black citizens in Portland, let alone the whole of Oregon during World War II, the calls for division amongst blacks and whites in Vanport City may also have been a byproduct of Southern influx and influence, attitudes perpetuated by both whites and blacks from that region. Vanport City residences themselves were segregated, with 2 neighborhoods specifically designed to house black workers.

According to Kessler in 1945:

Racial segregation is one of the problems which has colored the entire East Vanport community organization. It cannot be discussed under any one heading since it is like an unbroken thread reappearing in every pattern of the community cloth.

Interactions between whites and blacks within Vanport was discouraged. In Rising Anxieties, Rising Waters the detainment of a which man for walking through a black neighborhood is recounted in detail, while “mixed dances” at the community center drew attention from the HAP. Relying heavily upon transcripts from HAP board meetings for her thesis All’s Fair in War and Housing, Sarah Alexander writes:

The Housing Authority and the Sheriff of Multnomah County were in accordance with each other that blacks and white should be separated in Vanport City. From a law officer’s standpoint, interracial mixing could lead to violence, and so it would be best to separate the races in the context of recreation and extracurricular activity. …They discussed segregating not only the housing, but also the community buildings, which were supposed to be integrated on the project.

The Vanport school system however, was a fully integrated institution and remained as such.

What we know of Vanport we owe to the recollections of its surviving former residents, most of whom were young children while living there. According to Kessler, a whopping 54% of East Vanport residents were under the age of eighteen in 1945. It makes sense that what positive views they have--especially owing to race relations--would stem from their own experiences, the majority of which would have occurred while at school.

Vanport City vacation school, date unknown (travelportland.com)

Most Vanport adults were working one of three shifts, forcing the whole of Vanport City to operate on a three-shift time clock. Thus in a typical Vanport family, both parents worked, possibly on the same schedule. If both parents worked a graveyard shift (12 am to 8am), seeing to children was a problem.

Anticipating the need for childcare, the Vanport school system became a makeshift daycare center for its students. The teachers, like the rest of Vanport, took to working in shifts. “[W]e sought to make the schools the center of living for the children,” wrote the collective educators in 1947. A “twenty-four hour program” was instituted, and the teacher took on the role of caregiver.

In this complicated schedule of living, children attended school, received extended care with chance for recreation, meals and sleep, and spent but a few hours out of the twenty-four at home with family.

Still, many parents opted to leave their small children with neighbors or home with older sisters. According to Lunin Boyle, the school offered it’s after hours services for a nominal fee ($3.00), which may have been off-putting.

Many parents also disagreed with the Vanport schools' curriculum. As detailed in the Handbook of General Information for Teachers of Vanport City, reprinted in Lunin Boyle’s thesis, the Vanport school system took the view that “more than academic “growing up is not an intellectual process, it is essentially an emotional process,” and posited that “more than academic instruction and supervision” was required. Owing to the perceived de-emphasis on basic academics, many adults felt Vanport schools were sub par. When compared to the experiences within other school systems across the country, Vanport schools were found lacking by 71% “of those who express an opinion concerning the schools” in Lunin Boyle’s thesis. Racial integration received 7% disapproval .

Due to the school’s stringent racial integration policy, what segregation Vanport children experienced was comparatively minimal. The disconnect between Vanport dwelling adults and the greater community, with class and race reasserting themselves as common dividers, would have been experienced by the children peripherally.

Ironically, E. Shelton Hill insists that what segregation did exist ended with the dissolution of Vanport City and the need for Vanport’s black citizens to relocate within the larger community. Portland schools in particular were forced by the flood to admit black students many years before they would have moved towards integration.

Vanport, by Manly Maben (via freepages.history.rootsweb.ancestry.com)

Though the end of World War II and constant strife kept Vanport’s residents in a state of flux, with some records claiming residents left “at the rate of 100 a day” in 1944, Vanport soldiered on. It was not until the city itself washed away in 1948 that all remaining residents evacuated.

6000 Kids from 46 States. Vanport City Schools, Portland 17, Oregon. 1 edition: 1947. Primary source.

Alexander, Sarah. “All’s Fair in war and Housing: The Administration of Vanport City, Oregon by the Housing Authority of Portland--1942-1948”. Thesis, Lewis & Clark College. 2003.

Hill, E. Shelton. Interview with E. Shelton Hill, conducted by L.A. Barrie. 1976.Primary source.

Housing Authority of Portland, Oregon. Residents Handbook, Vanport. Web Nov. 2010. http://www.ccrh.org/comm/slough/primary/rules.htm

Kessler, Lillian. “The Social Structure of a War Housing Community--East Vanport City”. Thesis, Reed College Library. 1945, c.2

Kilbourn, Charlotte & Lantis, Margaret. “Elements of Tenant Instability in a War Housing Project.” American Sociological Review, vol. 11, no. 1. (Feb, 1946): 57-66. Rpt. in American Sociological Association

Local Color. By Jon Tuttle, 1991. Oregon Public Broadcasting, Documentary Unit, 1999. 29, Nov 2010. http://www.watch.opb.org/video/1593884540#

Lunin Boyle, Hope. “Effect of Living in Vanport City on the Behavior Patterns of Its Inhabitants”. Thesis, University of Oregon. 1946.

Maben, Manly. Vanport. Oregon Historical Society, Portland. 1987.

Tsalbrin, Sarah Demetria. “Rising Anxieties, Rising Waters: Interpreting the Politics of Race and Housing in Vanport City”. Thesis, Reed College Library. 2007, c.2

Charlotte Kilbourn and Margaret Lantis, “Elements of Tenant Instability in a War Housing Project” American Sociological Review, vol. 11, no. 1 Feb, 1946: 62

Lillian Kessler, The Social Structure of a War Housing Community--East Vanport City (Portland: Reed College, 1945) 27.

Sarah Tsalbrin, Rising Anxieties, Rising Waters: Interpreting the Politics of Race and Housing in Vanport City (Portland : Reed College, 2007) 11.

Sarah Alexander, All’s Fair in War and Housing: the Administration of Vanport City, Oregon by the Housing Authority of Portland--1942-1948 (Portland: Lewis & Clark College, 2003) 33.