Leaves of Grass

From 1850s

[edit] Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

"I sing the body electric the bodies of those I love engirth me and I engirth them"

[edit] Walt Whitman

Leaves of Grass.

Leaves of Grass. By: Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman or as he was later known, The Good Gray Poet, was born on a small farm on Long Island, and was the second out of nine children born. His parents were working class people, his mother of Dutch ancestry and his father of English descent. He embraced his dualistic heritage and continued to be influenced by it. He left school at the age of eleven to go to work for an attorney. However, he would continue his education informally with the circulating library and other businesses he was employed at. When he was sixteen he found work as a printer's apprentice in Manhattan. However, a fire destroyed most of New York's printing industry; but he was able to use the skills learned as a printer to find work in the journalism industry. In 1836, he began a six-year stint as a schoolteacher. It was during this time that he was able to find some relief from the boredom and stress of teaching by working on the newspaper he started himself, The Long Islander. Although this paper only lasted a year, other papers would occasionally reprint his work. This paper also led to employment at other publications, one of these publications was The Sun-Down Papers. This was probably the first time that the literary genius of Walt Whitman was first published. Whitman continued writing poetry and stories. During the 1840's he was finally able to support himself as a journalist. He was editor of The Aurora, a well-known New York daily. Where he wrote about local issues and made contributions to other publications. Whitman left New York for Brooklyn in 1845 but maintained a connection with the city. In 1848 he traveled to New Orleans with his younger brother to begin working for a newspaper there. Although this position did not last long, he was impacted by his time in New Orleans. Whitman returned home to New York with a renewed sense of appreciation for his home city. Upon his return to Brooklyn, he joined the Free-Soil Party and served as a delegate during their national convention. He also served as editor for their newspaper, The Brooklyn Weekly Freeman. Out of financial necessity, he opened a small store. The store became a print shop that he managed with his brother, Jeff. They sold the store after it had been open for three years. In the early 1850's he was motivated to write by national events. Whitman wrote Dough-Face Song, Blood-Money, The House of Friends, and Resergemus in protest of the Fugitive Slave Law. Eventually, Resergemus would be incorporated into Leaves of Grass under the title Europe, the 72nd and 73rd Years of These States. It was on July 4, 1855 that he released the first edition of his book. Whitman’s work in journalism contributed to the publication of his books. "Grass" was a term used by printers to describe work that they had written themselves. "Leaves" was a reference to pages. He used his connections in the journalism industry to publish and promote the book. Whitman wrote anonymous self-reviews and called himself "An American Bard. Even though the book didn't sell many copies it made quite an impression on the literary scene. Critiques ranged from being thoroughly outraged to mildly appreciative. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote him a letter containing the now famous words I greet you at the beginning of a great career. The next edition was published and contained a copy of Emerson's letter to Whitman along with Whitman's response. Over the years, Whitman revised Leaves of Grass several times. What had began as a small book that contained twelve poems became a larger book with almost four hundred poems. When the Civil War began, it had a profound effect on Whitman’s life. He wrote various recruitment poems, however he seemed determined to avoid the reality of war. This was until the war hit home and he learned that his brother had been injured. Whitman found his brother safe but was motivated to stay in Washington and help with the war efforts, and became a wound dresser at the hospitals. He provided comfort to all who needed it, whether they were Union or Confederate. Eventually the time and effort that he was putting into caring for the wounded started to take its toll on his health and he returned home to rest, but came back to nurture the wounded. At the end of the war he had been reduced to a physical wreck. In 1873 he was devastated by the death of his mother, it was about this time that he had a paralytic stroke from which he never fully recovered. He was forced to leave Washington and move in with his brother George in Camden, New Jersey. Over time he was able to buy a house on Mickle Street, where he passed away on March 26, 1892 among the company of his admirers. Leaves of Grass was published by Whitman six times during his life, and there is a seventh edition known commonly as 'the death bed' edition which Whitman was working on before he died. The first edition was published in 1855 and was released on July 6, 1855. Whitman publised this edition with the help of two brother; Thomas and James Rome. They printed 705 copies, 200 of which were bound in expensive cloth. This edition contains Whitman's most original work and is said to have the clearest and strongest voice of Whitman. A small book with only twelve poems, Whitman was able to sell it in a store in Brooklyn and in New York. A rush of creativity led him to publish his second edition only a year later, on September 11, 1856. This beautiful book, which was bound in forest green cloth and had gold writing, was a complete failure. The public was shocked by Whitman's 32 poems that contained open discussion about sexuality. This edition also contained a personal and private letter from Emerson congratulating Whitman on the beginning of a successful career. The third edition came out four years later in the spring of 1860. Whitman added 146 poems to the already existing 32. This was the first edition that Whitman put his poems into clusters; the book also contained illustrations. He also revised many of his old poems and altered their titles. Whitman had finished this edition by June of 1857 but had failed to find a publisher for two years. Finally, Thayer and Eldridge from Boston offered to publish his poetry. An estimated amount of 2,500 to 5,000 copies were published. It took Whitman another six years to get his fourth edition out. In November of 1866 the fourth edition was finally out. This edition was broken into four separate books, and contained only six new poems. Now known as the workshop edition, Whitman starts to show his democratic nationality in this edition. He had an opening poem titled Inscription, which introduced his book to the reader. Three years later in the summer of 1869 Whitman's fifth edition came out. Whitman was stuck in Washington D.C. for most of the summer and then had to work in the attorney general's office as a clerkship until July 1870 so the book did not go on sale until winter of 1870-71. He added another 120 pages to the book, which now contained 74 poems, 24 of them contained new titles and text since the last edition. It contained three separate books this time and a pamphlet called As A Strong Bird on Pinious Free, and other poems. Once again Whitman continued to write about politics and government. The last edition that Whitman was able to publish in his life was in 1822. The sixth edition had all of Whitman's finalized work. He cut out 39 poems completely and added 17 new ones. He then grouped his work into five clusters. James R. Osgood in Boston published this edition. Whitman also passed away later that year. The 'death bed' edition was published on the tenth year anniversary of Whitman's death and was the revised version of Whitman's work, with correct punctuation and correct format. Most of America did not buy or understand his book and were thrown by the overt sexuality of the poems. "Like many mystics, he was hypnotized by external phenomena, and often fails to communicate to his reader the trancelike emotion which he himself experienced. This imperfect transfusion of his material is a far more significant defect in Whitman's poetry than the relatively few passages of unashamed sexuality which shocked the American public in 1855." (Perry). Leaves of Grass represents the unity of the universe from Whitman’s experience with love, he felt that humanity has one heart and should have one will. The focus of his idea was on the individual first, then the collective mass of society. He approached moral questions on the assumption that moral values do not derive from society but from the individual. "Nearly everyone agrees that Walt Whitman is America's greatest poet…he is elusive, both as man and poet" (Unger). Whitman gives very little information about himself, one can speculate but never really know him. He describes Leaves of Grass as an autobiography "an attempt from first to last, to put a person, a human being (myself, in the latter half of the nineteenth century in America) freely, fully and truly on record." (Whitman). He projects a person (himself) through his poetry that is intellectual and unorthodox. He had a side to him that is described as "covert, bisexual, quirky, elusive, power-seeking, bohemian, libidinous, and indolent." (Unger). He was a maladjusted person during his time. Some critics view his "singing" in his poetry to be a celebration of America's material success. He celebrates the democratic man in many of his poems. He had a lifelong attachment to his mother (who was illiterate), it is speculated that because of this relationship he never successfully established his own sexuality. This is shown in his bisexual to homosexual tendencies. Whitman wrote for newspapers, taught school, was the editor for the Brooklyn Eagle, worked for the New Orleans newspaper the Crescent, and wrote and printed Leaves of Grass himself. Few people read Leaves of Grass when it was first published and it did not receive many favorable reviews, among them one or two Whitman wrote himself. He found his earliest fans to be in Europe, not America. When he did build a reputation in America it was as a prophet, not so much a poet. His readers often perceived his writing to be a mindless celebration of democracy, surprised by the use of satire. His use of sexual content was reviewed as startling for his time. I think another frustration for Whitman's readers is the fact that his work is difficult to read and he was hard to understand as a person. Whitman felt that in the postwar period honesty and purposefulness had been lost from life. He worried about chaos and fragmentation of American life and felt that people needed to focus more on their identity. His optimism of the future and lack of a historical views did not go over well with 20th century realism. He wanted moral and spiritual regeneration in America’s people and wanted people to exercise offices of moral and spiritual leadership that were once used for organized religion. Whitman saw himself as a philosopher and a priest, in Leaves of Grass he parallels the poet and priest throughout. His poems have a musical structure. He used repetition and parallelism, and restated lines; which built up momentum in his poems. This work was one that was very modern for his time. Whitman showed that poetry could be more than just following the rules. "His inner oppositions, his ambiguities, his wit, like his democratic faith, his optimism, and his belief in the self, are native to the man as they are to America. For these reasons one cherishes Walt Whitman-and takes him to be in a real sense 'the spokesman for the tendencies of his country." (Unger) "Do I contradict myself? Very well then...I contradict myself" (Whitman), this is a famous quote that has been taken less seriously. Whitman approved of the expanding society in America; he had serious reservations about the competitive origins. He solved this conflict by 'desocializing and naturalizing this energy' in his poetry, which helped him minimize the things that disturbed him. Whitman used nature in his poetry to express the importance to focus on the internal and the external. "Many Transcendentalists would certainly have agreed that man's intense preoccupation with external nature arises from his concern with his own essential or ultimate nature." (Whitman) Whitman wrote Leaves of Grass during a time when he was searching for his own identity, and America was in search of it’s own identity. “Leaves of Grass must, for this reason, be recognized ultimately as America’s great archetypal poem-as the national epic” (Miller) The body of Whitman’s book, as well as Whitman himself, evolved and matured over time. Paralleling this were many critic’s views of the work. When it was first released in 1855, Leaves of Grass was generally seen in a negative light. There were some critics who, in the midst of writing Whitman off, acknowledged the qualities of the book that redeemed it. An anonymous reviewer from The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote how the book, “…is a work that will satisfy few upon a first perusal; it must be read again and again, and then it will be to many unaccountable. All who read it will agree that it is an extraordinary book, full of beauties and blemishes…” and a few months earlier Charles A. Dana of The New York Daily Tribune clamed that Whitman’s poems were, “…full of bold, stirring thoughts-with occasional passages of effective description, betraying a genuine intimacy with Nature and a keen appreciation of beauty-often presenting a rare felicity of diction, but so disfigured with eccentric fancies as to prevent a consecutive perusal without offense, though no impartial reader can fail to be impressed with the vigor and quaint beauty of isolated portions.” There were also reviewers who seemed merely confused as to who Whitman was and why he chose to write in such a manner. “In glancing rapidly over the Leaves of Grass you are puzzled whether to set the author down as a madman or an opium eater; when you have studied them you recognize a poet of extraordinary vigor, nay even beauty of thought, beneath the most fantastic possible garments of diction,” wrote an anonymous reviewer for The New York Daily News. Yes, this reviewer seems to poke a bit of fun at Whitman, but he (or she) like so many other critics, acknowledges the redeeming qualities of Whitman’s work. The beauty mixed in among the vulgarity. The quaint scenes of Nature mixed in among the rude language. Not all critics of Leaves of Grass saw the positive side of the book. Many, in fact, saw it as a complete catastrophe; an abomination to the world of decent literature. Rufus Griswold of The Criterion absolutely hated the book and made sure that his opinion was perfectly clear in his review: “As to the volume itself…it is impossible to imagine how any man’s fancy could have conceived such a mass of stupid filth, unless he were possessed of the soul of a sentimental donkey that had died of disappointed love. The poet (?) [sic] without wit, but with a certain vagrant wildness, just serves to show the energy which natural imbecility is occasionally capable of under strong excitement.” Whitman’s entrance into the world of literature was not a smooth one. Although there were some who saw his work at its first publication, the way that 153 years later we would see his work, he still had many years of rocky road before him. It wasn’t until nearly 30 years after its original publication date that the public, accompanied by the critics, opened their eyes to Whitman. In between the first and last publications of Leaves of Grass were many more painful critiques. When the second edition was published just a year after the first, an anonymous reviewer for The Christian Examiner viciously attacked not only Whitman’s work, but Whitman, the man. At the beginning of his review, the critic is annoyed that, “these rank Leaves have sprouted afresh, and in still greater abundance.” The reviewer proclaims that since Whitman refuses to cease publishing the book that the reviewer must speak bluntly since it “is not a question of literary opinion principally, but of the very essence of religion and morality.” He goes on to refer to the book as “an impertinence towards the English language; and in point of sentiment, an affront upon the recognized morality of respectable people.” At the end of the review, the critic insults Whitman for publishing Emerson’s name on the back of his book, thereby associating the great Emerson with the awful Whitman. During the 1860’s the critics’ view of Leaves of Grass began to progress. Even so, the start of the decade saw negative and positive reviews side by side. Juliette H. Beach (The New York Saturday Press) writes of her disgust: “Whitman’s poems are not amorous; they are only beastly. They express far more truthfully the feelings of brute nature than the sentiments of human love…I doubt if, when Judgment-Day comes, Walt Whitman’s name will be called. He certainly has not enough soul to be saved. I hardly think he has enough to be damned.” Then Beach goes on to describe exactly how Mr. Whitman should commit suicide so as to prevent any future “suiciders” the shame of the leaving the world the same way as Whitman did. Another critic, who like so many others, sees the good within the bad of Whitman’s poems comments that “occasionally, a gleam of the true poetic fire shines out of the mass of his rubbish, and there are tender and beautiful touches in the midst of his most objectionable and disagreeable writings.” This anonymous reviewer for The New York Times also writes that, “it would be unjust to deny the evidences of remarkable power which are presented in this work.” Closer to the end of the decade we see much better reviews, such as the following: “Walt Whitman has at last justified himself. All his ‘hairy Pelasgic strength,’ all his vast abysmal power, have at last blossomed into a benevolence such as was never before the inspiration of poems,” written by John Burroughs for the Boston Commonwealth. In the early 1880s, everyone finally started to come around and enjoy Leaves of Grass instead of constantly criticizing it. The book was picked up by a publishing house (Whitman had been publishing it on his own prior to the book being issued by James R. Osgood & Co.) and the reviews that came out began more and more to praise Whitman for his genius. These reviews began stating things like “Whitman will take a permanent place in history as the father and founder or a distinctly American literature” (The First American Poet), “…much of the criticism [of Whitman’s work] is due to failure to understand…the beauty of the thoughts expressed cannot be denied…” (Walt Whitman. The Man and His Book-Some New Gems for Hs Admirers), and that “it would be easy to pick a thousand lines…that fairly breathe and bristle with power, that sparkle and flash with beauty, that are…unique in modern poetry” (Review of Leaves of Grass (1881-82)). So at the end of his life, having been hated by the public for most of his career, they finally come around to respecting Whitman for the true genius and legend that he is and always deserved to be. But never without one more jest at his unflinching determination to continue publishing Leaves of Grass: “But there is nothing in all Walt Whitman’s works, new or old, half so marvelous, or half so great a ‘curiosity of literature’ as the steady persistence of the author amid the nearly unanimous opposition (in this country at least) of orthodox criticism” (Walt Whitman’s Works, 1876 Edition).

Critique

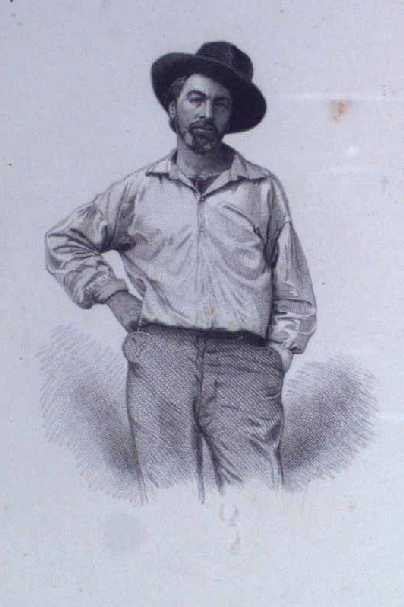

Here we have a book which fairly staggers us. It sets all the ordinary rules of criticism at defiance. It is one of the strangest compounds of transcendentalism, bombast, philosophy, folly, wisdom, wit and dullness which it ever catered into the heart of man to conceive. Its author is Walter Whitman, and the book is a reproduction of the author. His name is not on the frontispiece, but his portrait, half length, is. The contents of the book form a daguerreotype of his inner being, and the title page bears a representation of its physical tabernacle. It is a poem; but it conforms to none of the rules by which poetry has ever been judged. It is not an epic nor an ode, nor a lyric; nor does its verses move with the measured pace of poetical feet—of Iambic, Trochaic or Anapaestic, nor seek the aid of Amphibrach, of dactyl or Spondee, nor of final or cesural pause, except by accident. But we had better give Walt's own conception of what a poet of the age and country should be. We quote from the preface: "Other States indicate themselves in their deputies, but the genius of the United States is not best or most in executives or legislatures, nor in its ambassadors or authors, or colleges, or churches, or parlors, nor even in its newspapers or inventors; but always most in the common people, their manners, speech, dress, friendship—the friendship and candor of their physiognomy—the picturesque looseness of their carriage—their deathless attachment to freedom—their aversion to anything indecorous, or soft or mean, the practical acknowledgment of the citizens of all other States—the fierceness of their roused resentments—their curiosity and welcome of novelty—their self-esteem and wonderful sympathy—their susceptibility of a slight—the air they have of persons who never knew how it felt to stand in the presence of superiors—the fluency of their speech—their delight in music, the sure symptom of manly tenderness and native elegance of soul—their good temper and open handedness—the terrible significance of their elections—the President's taking off his hat to them, not they to him—these too are unrhymed poetry." But the poetry which the author contemplates must reflect the nation as well as the people themselves. "His spirit responds to his country's spirit; he incarnates its geography and natural life, and rivers and lakes. Mississippi with annual freshets and changing chutes, Missouri, and Columbia, and Ohio, and the beautiful masculine Hudson, do not embouchure where they spend themselves more than they embouchure into him. The blue breadth over the inland sea of Virginia and Maryland, and the sea of Massachusetts and Maine, over Manhattan Bay, and over Champlain and Erie, and over Ontario and Huron, and Michigan and Superior, and over the Texan, and Mexican, and Floridian and Cuban seas, and over the seas of California and Oregon, is not tallied by the blue breadth of the waters below more than the breadth of above and below is tallied by him. "To him enter the essence of the real things, and past and present events—of the enormous diversity of temperature, and agriculture, and mines—the tribes of red aborigines—the weather-beaten vessels entering new ports or making landings on rocky coasts—the first settlement North and South—the rapid stature and muscle—the haughty defiance of '76, and the war, and peace, and formation of the constitution —the union surrounded by blatherers, and always impregnable—the perpetual coming of immigrants—the wharf-hemmed cities and superior marine—the unsurveyed interior—the log houses, and clearings, and wild animals, and hunters, and trappers—the free commerce, the fishing, and whaling, and gold digging—the endless gestation of new States—the convening of Congress every December, the members duly coming up from all climates and the uttermost parts—the noble character of the young mechanics, and of all free American workmen and workwomen—the general ardor, and friendliness, and enterprise—the perfect equality of the female with the male—the large amativeness—the fluid movement of the population," &c. "For such the expression of the American poet is to be transcendent and new." And the poem seems to accord with the ideas here laid down. No drawing room poet is the author of the "Leaves of Grass;" he prates not of guitar thrumming under ladies' windows, nor deals in the extravagances of sentimentalism; no pretty conceits or polished fancies are tacked together "like orient pearls at random strung;" but we have the free utterance of an untramelled spirit without the slightest regard to established models or fixed standards of taste. His scenery presents no shaven lawns or neatly trimmed arbors; no hot house conservatory, where delicate exotics odorise the air and enchant the eye. If we follow the poet we must scale unknown precipices and climb untrodden mountains; or we boat on nameless lakes, encountering probably rapids and waterfalls, and start wild fowls never classified by Wilson or Audubon; or we wander among primeval forests, now pressing the yielding surface of velvet moss, and anon caught among thickets and brambles. He believes in the ancient philosophy that there is no more real beauty or merit in one particle of matter than another; he appreciates all; every thing is right that is in its place, and everything is wrong that is not in its place. He is guilty, not only of breaches of conventional decorum but treats with nonchalant defiance what goes by the name of refinement and delicacy of feeling and expression. Whatever is natural he takes to his heart; whatever is artificial (in the frivolous sense) he makes of no account. The following description of himself is more truthful than many self-drawn pictures: "Apart from the pulling and hauling, stands what I am, Stands amused, complacent, compassionating, idle unitary, Looks down, is erect, bends an arm on an impalpable certain rest, Looks with its side-curved head curious, what will come next, Both in and out of the game, and watching and wondering at it." As a poetic interpretation of nature, we believe the following is not surpassed in the range of poetry: "A child said, What is grass! fetching it to me with full hands; How could I answer the child! I do not know any more than he. I guess it is the handkerchief of the Lord; A scented gift and remembrancer, designedly dropped, Bearing the owner's name someway on the corners, that we may see, and remark, and say, Whose? We are afforded glimpses of half-formed pictures to tease and tantalize with their indistinctness: like a crimson cheek and flashing eye looking on us through the leaves of an arbor—mocking us for a moment, but vanishing before we can reach them. Here is an example: "Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore; Twenty-eight young men, and all so friendly. Twenty-eight years of womanly life and all so lonesome. She owns the fine house by the rise of the bank; She hides handsome and richly drest aft the blinds of the window. Which of the young men does she like the best? Ah, the homeliest of them is beautiful to her. Dancing and laughing along the beach came the twenty-ninth bather; The rest did not see her, but she saw them, &c." Well, did the lady fall in love with the twenty-ninth bather, or vice versa? Our author scorns to gratify such puerile curiosity; the denouement which novel readers would expect is not hinted at. In his philosophy justice attains its proper dimensions: "I play not a march for victors only: I play great marches for conquered and slain persons. Have you heard that it was good to gain the day? I also say that it is good to fall—battles are lost in the same spirit in which they are won. I sound triumphal drums for the dead—I fling thro' my embouchures the loudest and gayest music for them. Vivas to those who have failed and to those whose war vessels sank in the sea. And to those themselves who sank into the sea. And to all generals that lost engagements, and all overcome heroes and the numberless unknown heroes equal to the greatest heroes known." The triumphs of victors had been duly celebrated, but surely a poet was needed to sing the praises of the defeated whose cause was righteous, and the heroes who have been trampled under the hoofs of iniquity's onward march. He does not pick and choose sentiments and expressions fit for general circulation—he gives a voice to whatever is, whatever we see, and hear, and think, and feel. He descends to grossness, which debars the poem from being read aloud in any mixed circle. We have said that the work defies criticism; we pronounce no judgment upon it; it is a work that will satisfy few upon a first perusal; it must be read again and again, and then it will be to many unaccountable. All who read it will agree that it is an extraordinary book, full of beauties and blemishes, such as nature is to those who have only a half formed acquaintance with her mysteries.