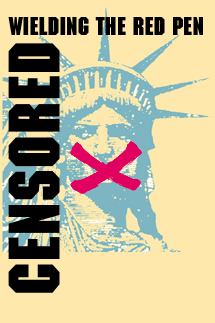

Literary Censorship

From 1850s

[edit] Sites of Interest

The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin [1]

Uncle Tom's Cabin Reconsidered [2]

The Wrath of . . . . Grapes? [3]

Uncle Tom's Children Why has Uncle Tom's Cabin survived—and thrived? Essay links inside [4]

What We've Made of Uncle Tom [5]

Don't Blame Uncle Tom [6]

Digging Through the Literary Anthropology of Stowe's Uncle Tom [7]

Literature in Elementary Cirriculum - 1913 [8]

Uncle Tom's Cabin in Frederick Douglass' Paper: An Analysis of Reception [9]

Banned Children's Books [10]

The Censored 11 [11]

Wikipedia List of Banned Books [12]

[edit] The Independent

Unsigned New York: 22 March 1855 AMERICAN TRACT SOCIETY EFFECTS OF ITS POLICY AT THE SOUTH.

A FRIEND of ours was in New-Orleans a few weeks ago. He saw in some of the Northern newspapers the then current notices of the "Southside View" by Dr. Nehemiah Adams; and having had some opportunities for a south-side view of his own, he naturally had some curiosity to see just what report Dr. Adams had carried back to New-England. Accordingly he made inquiry among the booksellers of that great Southern emporium, but the "South-Side View" was not to be found, and had not been heard of in that market. he found, however, that "Uncle Tom's Cabin," and "Ida May" were on sale, openly, in all the bookstores. So he came to the conclusion that the book he was inquiring for, might have been sold, without any great peril, in the Southern market, if there had been any sufficient demand for it.

It is not to be supposed that every book on Slavery can be sold in the slave-holding States without hindrance from the censorship there established. When "Uncle Tom's Cabin" first made its appearance, it could not have been offered for sale any where south of the Potomac, without exposing the vendor and the purchases to the terrors of Lynch-law. But after the work had filled the world with its fame; and an acquaintance with it had become a matter of inevitable necessity to every person who would not be regarded as a mere ignoramus, intelligent people in the Southern States would not—and therefore could not—be hindered from reading it. So the censorship was compelled to give way. "Uncle Tom's Cabin" (pictures and all) could not be suppressed, for the same reason that Cowper's Poems, Paley's Moral Philosophy, the Bible, and the Congressional Globe, (with all its "incendiary matter," so-called) cannot be suppressed. And what is the reason? Just this; intelligent and respectable persons in the Southern States want those books, and will have them; therefore, they will not surrender their liberty in that respect for the sake of pleasing the slave-traders and the demagogues. Consequently, the slave-traders, and their dependent partners the demagogues, find themselves under the necessity of keeping silence. The men and women who will have those books, and who will not surrender their liberty in that respect without a desperate struggle, are so many, so respectable, so influential in society, so powerful by their wealth and their position, that a conflict with them would be dangerous. it might not be easy to call out the mob against them.

The policy of the American Tract Society has assumed, from the first, that if the Society should venture to recognize in any of its publications the notorious facts which make up the concrete of American slavery—still more, if it should apply to any of those facts the rules and principles of the Christian religion—all its tracts and books would be excluded by mob violence from every slave-holding State. What have been the results of that policy in the South? What is its natural tendency. That policy continually aggravates the very danger before which it trembles. it acknowledges the existence—and in effect the legitimacy—of a power throughout the Southern States which will permit no man to utter a Christian word, or even to think a Christian thought, in regard to crimes and vices that are the horror and the shame of Christendom. For fear of that power, not a word must be uttered against robbing the poor of their wages—not a word for the God-given "right of property" which the poor man has in his own labor. For fear of that power, not a word must be uttered to show that the man who, having the might, assumes the right to take away children from their parents, and to separate wives from their husbands, at his own convenience or caprice, in defiance of the laws of God—must repent of his wickedness or perish in it. For fear of that power, not a word must be uttered against the slave-trade—not a word to show that the slave-trader (whose profession and employment is beyond comparison the most damnable on earth) is in the way to hell. The Executive Committee, sitting in this great and free metropolis has been acting for thirty years upon the policy of yielding silent but absolute deference to that power. And for thirty years that power which so oppresses the South—crushing out of the churches there all freedom of action, of speech, and of thought in regard to slavery—has been continually strengthening itself, and making itself more insolent and imperious, by the tribute which the Tract Society pays to its authority without even a protest against its legitimacy. The Southern churches, instead of asserting with Christian manliness their independence of the fiendish power that oppresses them—as they might have done long ago had they been left entirely to themselves—have grown more cowardly, more helplessly fettered, more enslaved in thought and spirit, by their connection with this great Northern institution for evangelical effort, and with other similar institutions that have pursued a similar policy.

An illustration of how the policy of the Tract Society is working at the South, came lately to our knowledge. Those well-known publishers of Presbyterian books, the Messrs. Carters, republished a few years ago, the "memoir of Mary Lundie Duncan," copying the original edition without any change or mutilation. The work, as it came from their press, was sold at the South without hindrance or objection from any quarter. It was, in fact, quite as popular among their Southern customers as anywhere. Afterwards the same work, as is well known, was published by the Tract Society, but not till it had been trimmed and expurgated in deference to the ruffian power before which the Society habitually trembles. And now at last, the Messrs. Carters find themselves denounced at the South, for not having been forward to do what the Tract Society had done. Their recent edition of a work of Rev. John Angell James, in which Topsy is alluded to by way of illustration, has been repudiated by the Southern press, in quarters where all his works have hitherto gone unchallenged. The example of the Tract Society testifies, in effect, that it was wrong in those honest Old-School Presbyterian publishers to issue from their press even so simple and harmless a book as that, without first taking care to mutilate it in homage to the imperial power of the slave-trading interest. Jefferson_Village