African American Perspective

From 1850s

Most of the reviews of Uncle Tom's Cabin come from the majority of the population, the whites. So I thought it would be interesting to follow how African Americans have viewed this piece of literature over time. I was particularly interested in how they viewed the book when it was first published, and then when it begins to be seen as not helping the African American cause but continuing racial stereotypes. Even though it has been touted as bringing the evils of slavery to the publics’ attention, it is obviously not an actual portrayal of how harsh slavery was, and it also has many racial connotations throughout. So I have looked at different time periods starting with how it was viewed when it was first published in the 1850s, through the civil rights movement, and to where it stands today with African Americans.

Contents |

[edit] 1850s

It appears that free blacks, in the United States, during this time period were ready to accept any help they could get from the privileged whites. But that the blacks further north, in Canada, were able to speak more openly on their feelings of the novel. That is why I chose a newspaper from each perspective. One great concern held by those blacks who opposed the novel was Harriet Beecher Stowe sending George off to Liberia. They felt that this was a very white person thing to do, just drive the blacks out of the country and then they don't have to be dealt with at all.

Published in Rochester, N.Y. from 1851-1860 by abolitionist and ex-slave, Frederick Douglass. This paper was in great support of Uncle Tom's Cabin and Harriet Beecher Stowe. But there are a few letters printed from Martin R. Delany, a free black, in protest of Ms. Stowe. He believes she can't truly help with African American struggles because she is a white New England woman who he believes to be a Colonizationalist.[1]

- 1852, April 1 -- "Literary Notice," unsigned but probably by Frederick Douglass

"UNCLE TOM'S CABIN, or LIFE AMONG THE LOWLY, By Harriet Beecher Stowe. 2 vols. Boston, John P. Jewett and Co. This work has not yet reached us, from the publishers: but when we hear that the first edition of five thousand copies (issued on the 20th of March) was sold in four days, we are not surprised at the delay. This thrilling Story, from the accomplished pen of Mrs. Stowe, has appeared week after week, by installments, in the National Era, and has been perused with intense interest by thousands of people. The friends of freedom owe the Authoress a large debt of gratitude for this essential service, rendered by her to the cause they love. We are well sure that the touching portraiture she has given of "poor Uncle Tom" will, of itself, enlist the kindly sympathies, of numbers, in behalf of the oppressed African race, and will raise up a host of enemies against the fearful system of slavery. Mrs. Stowe has, in this work, won for herself a place among American writers—She has evinced great keenness of insight into the workings of slavery, and a depth of knowledge of all its various parts, such as few writers have equalled, and none, we are sure, have exceeded. She has wonderful powers of description, and invests her characters with a reality perfectly life-like. Fine as she is in description, she is not less so in argumentation. We doubt if abler arguments have ever been presented, in favor of the "Higher Law" theory, than may be found here. Mrs. Stowe's truly great work, is destined to occupy a niche in every American Library, north of 'Mason and Dixon's Line.'"

- 1853, March 4 -- "A Day and a Night in 'Uncle Tom's Cabin'," Frederick Douglass

Excerpt: "The object of our visit was to consult with the authoress, as to some method which should contribute successfully, and permanently, to the improvement and elevation of the free people of color in the United States—a work in which the benevolent lady designs to take a practical part; and we hesitate not to say that we shall look with more confidence to her efforts in that department, than to those of any other single individual in the country. In addition to having a heart for the work, she, of all others, has the ability to command and combine the means for carrying it forward in a manner likely to be most efficient. She desires that some practical good shall result to the colored people of this country, by the publication of her book—that some useful institution shall rise up in the wake of "Uncle Tom's Cabin."—The good lady, after showing us, in the most child-like manner, any number of letters, in testimony of the value of her book, together with presents of various kinds, among the number the beautiful "BRONZE STATUE OF A FEMALE SLAVE," entered most fully into a discussion with us on the present condition and wants of 'the free colored people.'"

- 1853, April 1 -- FIRST Letter from M.R. Delany with remarks by Frederick Douglass

Excerpt from Martin Delany in respone to Frederick Douglass' visit with Harriet Beecher Stowe: "FREDERICK DOUGLASS, ESQ.: DEAR SIR:—I notice in your paper of March 4 an article in which you speak of having paid a visit to Mrs. H. E. B. Stowe, for the purpose, as you say, of consulting her, "as to some method which should contribute successfully and permanently, in the improvement and elevation of the free people of color in the United States." Also, in the number of March 18th, in an article by a writer over the initials of "P. C. S.," in reference to the same subject, he concludes by saying, "I await with much interest the suggestions of Mrs. Stowe in this matter." Now, I simply wish to say, that we have always fallen into great errors in efforts of this kind, going to others than the intelligent and experienced among ourselves; and in all due respect and deference to Mrs. Stowe, I beg leave to say, that she knows nothing about us, "the Free Colored people of the United States," neither does any other white person—and, consequently, can contrive no successful scheme for our elevation; it must be done by ourselves. I am aware, that I differ with many in thus expressing myself, but I cannot help it; though I stand alone, and offend my best friends, so help me God! in a matter of such moment and importance, I will express my opinion. Why, in God's name, don't the leaders among our people make suggestions, and consult the most competent among their own brethren concerning our elevation? This they do not do; and I have not known one, whose province it was to do so, to go ten miles for such a purpose. We shall never effect anything until this is done."

Excerpt from Frederick Douglass' remarks towards Martin Delany's letter: "REMARKS—That colored men would agree among themselves to do something for the efficient and permanent aid of themselves and their race, "is a consummation devoutly to be wished;" but until they do, it is neither wise nor graceful for them, or for any one of them to throw cold water upon plans and efforts made for that purpose by others. To scornfully reject all aid from our white friends, and to denounce them as unworthy of our confidence, looks high and mighty enough on paper; but unless the back ground is filled up with facts demonstrating our independence and self-sustaining power, of what use is such display of self-consequence? Brother DELANY has worked long and hard, he has written vigorously, and spoken eloquently to colored people—beseeching them, in the name of liberty, and all the dearest interests of humanity, to unite their energies, and to increase their activities in the work of their own elevation; yet where has his voice been heeded?"

- 1853, April 29 -- SECOND Letter from M.R. Delany

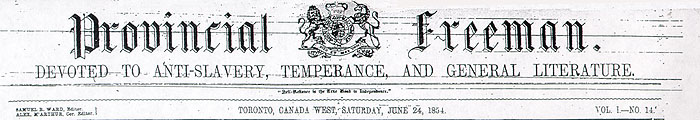

Published in Toronto, Canada from 1854-1857. The editor was Samuel B. Ward, a former slave. The publishing agent was Mary Ann Shadd Carey, the daughter of free blacks, she was the first African American woman publisher in North America. This paper differed from most written by blacks in this time period in its agressive critique of Uncle Tom's Cabin. [2]

- 1854, July 22 -- "George Harris"

Excerpts: "One of the most manly specimens of oppressed human nature, in "Uncle Tom's Cabin," is George Harris. The manner in which Mrs. Stowe disposes of him, and the words she puts into his mouth, as reasons for his going to Liberia, always struck us as a piece of needless and hurtful encouragement of the vile spirit of Yankee Colonizationism."

"Uncle Tom must be killed,—George Harris exiled! Heaven for dead negroes!—Liberia for living mulattoes! Neither can live on the American Continent! Death or banishment is our doom, say the Slaveocrats, the Colonizationists, and,—save the mark,—Mrs. Stowe!"

[edit] Prior to the Civil Rights Movement

There were not a lot of articles written about Uncle Tom's Cabin in African American publications until the Civil Rights Movement. But I was able to find a few examples before the Civil Rights Movement that help give insight into how African Americans viewed the novel. It appears they are still in acceptance of the novel for its historical significance, but the idea of the novel being racist and perpetuating racial stereotypes is starting to show with the groundbreaking essay, "Everybody's Protest Novel," by James Baldwin in 1949.

- 1916, October -- "Review of: Race Orthodoxy in the South and Other Aspects of the Negro Problem," Robert E. Park, The Journal of Negro History

Excerpt: "The criticism of this book is so subtle that it is difficult to indicate the outlines of it in a single paragraph. The difficulty with Mrs. Stowe's interpretation of the South and the Negro is that she, just as certain Southern humanitarians of the present day, is inclined to treat the Negroes as a class. She does not regard them as a race, a different breed, whose blood is a contamination. "No one," says the writer, "has come within shouting distance of the real Negro problem who does not appreciate this distinction. Indeed, almost everything critical that can be alleged against 'Uncle Tom's Cabin' springs from the failure of its humanitarian author to sympathize with race consciousness as such."

- 1938, January -- "Review of: Harriet Beecher Stowe's Biography, William H. Ferris, The Journal of Negro History

Excerpt: "The world has known of the dramatic appeal of Uncle Tom's Cabin, and of the arresting power of "Uncle Tom" and the other characters for eighty-five years. Mrs. Gilbertson's biography will give some insight into the genius and personality of the gifted novelist."

- 1949, 1st Qtr. -- "Book Notes: Uncle Tom's Cabin," Phylon

"UNCLETOM'S CABIN. By Harriet Beecher Stowe. The Modern Libram. New York: Random House. xxiii, 552 pp. $1.25. Heretofore it has been almost impossible to obtain Harriet Beecher Stowe's novel in its entirety. This edition, complete and unabridged, makes available one of the most passionately humanitarian and influential books in America. Fortunately, a brilliant introduction by Raymond Weaver of Columbia University gives information that has not been generally available about Mrs. Stowe, the growth of the book, and its numerous editions and dramatizations."

Excerpt: "Uncle Tom's Cabin, then, is activated by what might be called a theological terror, the terror of damnation; and the spirit that breathes in this book, hot, self-righteous, fearful, is not different from that spirit of medieval times which sought to exorcize evil by burning witches; and is not different from that terror which activates a lynch mob. One need not, indeed, search for examples so historic or so gaudy; this is a warfare waged daily in the heart, a warfare so vast, so relentless and so powerful that the interracial handshake or the interracial marriage can be as crucifying as the public hanging or the secret rape. This panic motivates our cruelty, this fear of the dark makes it impossible that our lives shall be other than superficial; this, interlocked with and feeding our glittering, mechanical, inescapable civilization which has put to death our freedom."

[edit] Civil Rights Movement

With the civil rights movement comes the realization that Uncle Tom’s Cabin is no longer helping the African American cause. It is believed that the racism and stereotypes, even though they were written in a different time period, have perpetuated the segregation of blacks and whites. There is much discussion on the racial stereotypes created by UTC, and whether they were perpetuated by the novel or the numerous "Tom Shows" that evolved over time becoming more disgusting and straying from the main themes of the book. I expected to find these critiques when I started researching, but I was surprised by how many article also recognize that Harriet Beecher Stowe lived in a completely different time period, and with different scientific knowledge. That UTC is just a sign of the times, it was never a truly realistic story, it can be recognized as serving a purpose in the past but that it is not relative in more current times.

- 1956, 3rd Qtr. -- "Review of: Goodbye to Uncle Tom, James A. Hulbert, Phylon

Excerpt: "In this work Mr. Furnas has taken up mighty arms on behalf of the Negro, democracy, and common sense. It is his thesis that the Abolitionist classic, Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin," recently included in Robert Downs' "Books that Changed the World," has been chiefly responsible for the conception and perpetuation of the most prevalent and damning stereotypes in the thinking of whites about Negroes. He is a severe critic of Mrs. Stowe's research, content, characterizations, and knowledge about race. The tremendous influence of the book, extended by the innumerable "Tomshows" and black-faced minstrels of Eliza and the hounds, and Simon Legree fame, has been more than just effective propaganda leading to the Civil War. "Uncle Tom's Cabin," says Furnas, has been the source of much of the wrongheaded thinking and unfair misconceptions about race in this country. The relation of all this to today's dilemma of desegregation is obvious."

Excerpt: "Thus Harriet Beecher Stowe engaged the popular reader and, having beguiled him with sentiment and mythology, stirred up his indignation against slavery. No doubt Furnas is right in pointing out that the most lasting impression of Uncle Tom is its stereotyped portrayal of the Negro character. And it is well to banish the stereotypes. But while exposing the sentimentality and condescension of some abolitionists, it is unjust not to recognize how vital was their contribution to the cause of liberty. Moreover, to attribute the stereotyping and the long-standing biases to Mrs. Stowe, as if she were alone their creator, is absurd. Stereotypes grow out of realities about which Americans feel guilty. They are the wish fulfillment of a ruling caste; they seem to mitigate the oppression of the Negro by showing him to be rather sub-human. Their raison d'e'tre is, therefore, sociological. Yet there is a curious ambivalence in these Negro stereotypes, for while they dramatize the contempt of white America, they also suggest a certain wonder, respect and praise for the minority group. In Uncle Tom Mrs. Stowe is saying as Faulkner does in The Sound and Fury, "They were better than we. They endured." Mrs. Stowe accomplished more by presenting the maudlin picture of Tom's long-suffering Christianity than Furnas is likely to achieve by raising the specter of "Negro genes" in the blood of the white population. But surely both Lincoln and Furnas exaggerate her influence. For had she never written a word the Civil War would have been fought and the American attitude toward the Negro would be much the same. It seems to me that, not only her intentions, but the original impact of Harriet Beecher Stowe's book as an antislavery influence were good. As Parrington said, she "brought the system home to the common feeling and conscience." In her second novel, Dred, she showed how much more she had learned about the economic basis of slavery and southern society. It is a book which placed her squarely among the liberal thinkers of the time and paved the way for the realistic treatment of the life of the South in modern fiction."

- 1963, 1st Qtr. -- "Another View of 'Uncle Tom,'" Benjamin F. Hudson, Phylon

Excerpt refering to Goodbye to Uncle Tom by J. C. Furnas, discussing how the stereotypes in UTC stemmed from the 'Tom shows' and not necessarily Stowe's novel.

"J. C. Furnas, in his scathing denunciation of Mrs. Stowe's novel, suggests the possible reasons for the disrepute into which the term, "Uncle Tom," has fallen. He points out how the play adaptions of Uncle Tom's Cabin, initiated successfully by George L. Aiken, swept across the United States and then Europe, becoming a veritable gold mine for troups of actors. The various versions became more and more repulsive and degenerated the characters of the novel for monetary profit, thus creating even more distorted conceptions of the institution of slavery and the Negro slaves. Furnas calls attention to the omissions from and additions to the original story which created the present-day concept of Uncle Tom, and of the Negro in general. He concludes:

. . . Neither Aiken's script nor any successor included St. Clair's advice to Miss Ophelia about the laying on of hands. Tom-shows even accentuated Mrs. Stowe's notions of the superiority of 'white blood' by playing Eliza, George Harris and Cassie - the slave characters of energy and enterprise -with white actors using little if any dark make-up and eschewing Negro dialect. Only Tom, Topsy and the chuckle-headed minor characters were played as identifiable Negroes. A Tom-show made it unmistakable that a freedom seeking Negro must, by definition, have a great deal of 'white blood.' No wonder the American Negro hates the words, 'Uncle Tom,' and uses them to denounce what he sees as truckling treason to his people. But he should be aware that it was the show that carried the name rather than Mrs. Stowe's book, that most deserves his hatred. . . . The [Tom-]show was cold-blooded exploitation, flogging a dead horse for gain, a cynicism as monstrous as the decision to produce The Birth of a Nation (Ibid., pp. 283-84)."

A white man with his face painted black playing Uncle Tom:

Uncle Tom's Cabin, American Mutoscope & Biograph, 1903

- 1963, 3rd Qrt. -- "The Revival of Uncle Tom's Cabin," Robert Merideth, Phylon

Excerpt: "Nevertheless, Uncle Tom's Cabin remains an almost universally misunderstood book, and its revival - the causes of which are as many, and roughly the same, as the sources of our misreadings - is not altogether encouraging. First, the Negro revolt that began in the 1950's and moved towards a climax in the early '60's has forced a revaluation of the Negro as a human being. Not only white historians and intellectuals, but, more importantly, the grown-up children of Uncle Tom, to borrow from the title of Richard Wright's book, have become intensely sensitive to the stereotyping of Negroes, past as well as present. Instead of blaming the infamous 'Tom-shows' and popular distortion for Uncle Tom, Topsy, Aunt Chloe, and Sambo as stereotypes, they have blamed Mrs. Stowe. To blame her they have had to read her -anachronistically."

- 1969, Summer -- "Uncle Tom Becomes Nat Turner: A Commentary on Two American Heroes," Donald K. Pickens, Negro American Literature Forum

Excerpt: "In sum, Uncle Tom is the nineteenth century woman's ideal of the perfect male. Kindly, obedient, gentle, he never bullies; he is a Christian gentleman, noble in spirit, undemanding in physical wants. He is an admirable character. With all the disabilities that Mrs. Stowe places on Tom, the man remains true to his innermost convictions. He gives up his life for his fellow slaves, for by rejecting Legree's plan to make Torn a slave driver, Legree's two black helpers (who are real "Uncle Toms") beat Tom to death. Tom’s refusal to beat, to drive, the other slaves should please the most race conscious black critic. As a nonviolent objector, Tom quietly by losing his life champions the innate qualities of the black race. He becomes a saint whose spirit frees the slaves on his old Kentucky plantation and his cabin becomes a shrine. His gentleness of spirit wins the victory. Love reforms individuals and subsequently society. Christian quietism -- with Tom remaining morally pure -- softens the hearts of all. For a, nineteenth-century woman who wrote from her heart, Harriet Beecher Stowe created a remarkable hero. A stereotype often but a hero who remains true to his ideas and ideals and thereby transforms society through love. He reforms society by letting it kill him, the Christian gambit."

[edit] Present Day

It appears that after the Civil Rights Movement reviews of Uncle Tom’s Cabin are not as frequent. I was able to find one article written by a black author. But I don't want to generalize about the African American perspective during this time period because I don't have enough sources to draw from.

- 2006, December 25 -- "Uncle Tom's Shadow," Darryl Lorenzo Wellington, The Nation

Excerpt: "Harriet Beecher Stowe's strength and weakness was that she wrote in broad strokes. Her universe consisted of representative characters who embodied the attitudes, politics and poetry of daily life in antebellum America. Because her archetypal images simultaneously fascinated and unnerved her audience--that is, because they struck home--the book became a staple of popular culture, and her archetypes were debased into stereotypes: the Good Slave, the Tragic Mulatto, the Cruel Slavemaster. Uncle Tom's Cabin is deeply flawed, but it transcends these caricatures. While its intellectual content creaks, its images continue to haunt."

Contact me at lolar7@msn.com