ASSIGNMENTS

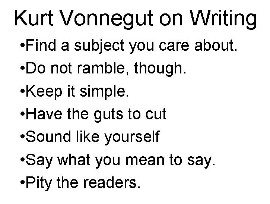

Here are the assignments. And here’s the truth: These assignments are just prompts to get you started on writing. Annie Barrett, in our yoga workshops, will often urge you to “play with the pose.” We urge you to play with these assignments. Like an asana there is a basic structure that should engage your attention. But the goal is not to “get it right.” The goal is to pay attention to what you do within the structure. The structure allows you the chance to exercise your freedom. We want to read not “good responses to the assignments”; we want to read good pieces of writing.

When we taught “Telling the Truth,” we had one writing assignment: Write about something important that others should know. It’s always the same in writing. You have to remember that you are taking time to do the work of writing, so you should work on something important. At the same time, a writer wants readers to take some of their time out of their “one wild and precious life” (Mary Oliver, “The Summer Day”) and read the work. So you should write about something others should know. That’s it. Always do that. Okay?

FIRST PARAGRAPH (due: 8:45 am, Wednesday, October 3)

Write one paragraph. Make it the opening paragraph of your final independent research project. The opening should be engaging. The ending should be snappy. After reading the paragraph, the reader should be eager. This is your first chance to get the reader ready to read your work. It's got to be good. Write the best paragraph you possibly can. Then re-write it. Then re-craft it. Then make it better. Then tinker with it. Then pass it through the usual review process (below). Then finalize your work and turn it in.

Review Process for all Writing: You must test the effectiveness of your writing before submitting it to the faculty by having colleagues in the program read and respond to the piece in writing. With your final version, you must submit to the faculty all your drafts and at least TWO readers’ comments and suggestions for revisions, along with their signatures and names. Write a short, two- or three-sentence summary of the feedback you got from your readers. This summary will be the cover page for the stapled packet you submit to your faculty member. That cover page should guide your faculty's response to your work. Try to figure out what further help you'd like and ask for it.

MORNING PAGES (due every day)

Julia Cameron, in The Artist’s Way, encourages students to engage in “an apparently pointless process I call the morning pages.” The morning pages, she writes,

… are three pages of longhand writing, strictly stream-of-consciousness: “Oh, god, another morning, I have NOTHING to say. I need to wash the curtains. Did I get my laundry yesterday. Blah, blah, blah…” They might also, more ingloriously, be called brain drain, since that is one of their main functions.

There is no wrong way to do morning pages. These daily morning meanderings are not meant to be art. Or even writing. … Pages are meant to be, simply, the act of moving the hand across the page and writing down whatever comes to mind. Nothing is too petty, too silly, too stupid, or too weird to be included.

… Nobody is allowed to read your morning pages except you. … Just write three pages, and stick them into an envelope. Or write three pages in a spiral notebook… Just write three pages … and write three more pages the next day.

As with your daily yoga practice, if you miss a day, no excuses and no big deal: begin your daily morning pages again the next morning.

PLAGIARIZE THIS (due: 8:45 am, Wednesday, October 10)

Good writers participate in the community of writers. The good ones, consequently, have a rich, broad pool from which to draw not “inspiration” (which is rather airy) but words, sentences, writing. Jean-Paul Sartre recalls in his autobiography, The Words, how he first became a writer by copying stories from his children’s periodicals. At first, he just copied them, word for word. Eventually, slowly, he developed his own style by, say, changing a character’s name or adding details copied from an encyclopedia. From this childhood experience of being a writer, Jean-Paul, the child, became Sartre, the writer. You might say that Sartre became the writer he did by first “becoming one with” other people’s stories and styles; simply being, while still a child, a writer (and doing so by engaging in a practice that any proper academic would call “plagiarism”) allowed him to become a great, unique stylist.

You will hear often in this program that we intend to “interrupt student habits.” This assignment tries to interrupt the habit of censoring your impulse just to copy someone else’s work. We want you to learn to plagiarize, and we want you to learn to do this well.

This assignment works in stages.

During the first stage, you're all attention, seeking out a passage or passages from works you have read that you wish you had written yourself. (Note: This requires you to pay attention to yourself, your desires, your inclinations, as well as to the texts.) Once you have selected the text you covet (“to feel blameworthy desire for that which is another’s,” “to wish for longingly”—AHD), you should spend a lot of time with it, writing it with a pen, re-typing it, maybe many times, until you get the feel of what it might have been like to write it yourself. Pay attention to words and phrases that come out of your pen easily. Pay equal attention to those that, perhaps, are not your words and phrases yet but that might become so. Pay attention to anything you absolutely cannot write.

During the second stage you write a piece about the passage, identifying stylistic features (sentence structure, syntax, words and word choices, tone, topic) that sum up its technical and aesthetic features and its effects on you as a writer who reads both to learn and to become a member of the community of writers.

During the third stage, you put the passage away—hide it well and allow yourself to visit it only in your imagination. In fact, you won't look at the passage again until after you have completed the entire assignment.

The fourth stage is when you recreate the passage—without looking back at it and taking as many liberties as you like in terms of topic but attempting to preserve elements of style and tone that bear a strong relationship to the original—without being silly about it. This final iteration should be a real piece of writing that owes a debt to a writer whose work has taught you something about your own craft.

Finally, set the original passage(s) next to your work. Admire both. Have your work reviewed by your colleagues and turn it in.

Make sure to have your work reviewed.

RULES OF WRITING PEER GROUP COMPETITION

(first submission due: 8:45 am, Wednesday, October 17). Faculty will announce the first winner(s) during week-five presentations. The contest will remain open throughout the remainder of fall and winter quarters. If we do not get submissions on a regular basis, we will, at our whim, announce another due date. Faculty will announce future winners whenever they feel like it.

Writing is a rule-bound activity. It has to be or it could not serve as a medium between people. You have  to learn the rules, all of them. One of the reasons for knowing all the rules—maybe we could also have a competition to establish justifications for learning the rules—is that you will know when you are breaking the rules. (Nadine Gordimer did not win the Nobel Prize in literature because she substituted em-dashes for quotation marks. But she did win the Nobel Prize, in part, because she knew what she was doing as a writer.) If you have to break the rules of writing, you should do so properly, deliberately, deliciously. You have to learn the rules of writing so you can know, in your bones, that writing is not a rule-bound activity.

to learn the rules, all of them. One of the reasons for knowing all the rules—maybe we could also have a competition to establish justifications for learning the rules—is that you will know when you are breaking the rules. (Nadine Gordimer did not win the Nobel Prize in literature because she substituted em-dashes for quotation marks. But she did win the Nobel Prize, in part, because she knew what she was doing as a writer.) If you have to break the rules of writing, you should do so properly, deliberately, deliciously. You have to learn the rules of writing so you can know, in your bones, that writing is not a rule-bound activity.

So, here’s the assignment: Make up some “Rules of Writing.” They can be universal rules, like those proposed by William Safire, e.g., “Remember to never split an infinitive,” “The passive voice should never be used,” “Proofread carefully to see if you words out,” “If you reread your work, you can find on rereading a great deal of repetition can be avoided by rereading and editing,” or “A writer must not shift your point of view.” Or you can make up rules for this class. Here’s one we made up after reading a sentence in which a writer used lots of slashes to show she didn’t know, and couldn’t find, the right word. “Slashes are not allowed, except in URLs (e.g., http://www.nytimes.com/) and/or in both/and’s.” Here's another rule: "Follow the New York Times's style for 'email' (i.e., don't write e-mail or e mail)." (It should go without saying that you have to follow both of these program rules.) (It should also go without saying that the second "program rule" would not win anything because it's utterly boring.)

Work as a peer group. Awards will be made only to groups. If you don’t have fun doing this, you’re not following the assignment.

Different Times, Different Places: One Story (due: 8:45 am, Wednesday, November 7)

You begin this assignment by identifying two different times or two different places that will form distinctive strands of a single narrative—strands that you will unify, imaginatively, without explaining anything to the reader.

Rather, the unity—the plot and purpose—of your story will emerge out of juxtapositions.

As you attend to the craft of description, the disparate strands of narrative will inexorably merge, each commenting on the other, each showing the reader something that could not be said within the scope of the other.

For instance, in his story, “Chicxulub,” T.C. Boyle describes the impact of meteors, one in Russia and another in Chicxulub, both in the past. In the present, unconnected to the meteoric annihilations, Boyle tells the story of a girl whose parents are informed of her death. Here are three paragraphs, the latter two "disconnected," in a sense, from the first:

The night of the Tunguska explosion the skies were unnaturally bright across Europe—as far away as London people strolled in the parts past midnight and read novels out of doors while the sheep kept right on grazing and the birds stirred uneasily in the trees. There were no stars visible, no moon—just a pale, quivering light, as if all the color had been bleached out of the sky. But of course that midnight glow and the fate of those unhappy Siberian reindeer were nothing at all compared to what would have happened if a larger object had invaded the earth’s atmosphere. On average, objects greater than a hundred yards in diameter strike the planet once every five thousand years and asteroids half a mile across thunder down at intervals of three hundred thousand years. Three hundred thousand years is a long time in anybody’s book. But if—when—such a collision occurs, the explosion will be in the million megaton range and will cloak the atmosphere in dust, thrusting the entire planet into a deep freeze and effectively stifling all plant growth for a period a year of more. There will be no crops. No forage. No Sun.

There has been an accident, that is what the voice on the other end of the line is telling my wife, and the victim is Madeline Biehn, of 1337 Laurel Drive, according to the I.D. the paramedics found in her purse. (The purse, with the silver clasp that has been driven half an inch into the flesh under her arm from the force of the impact, is a little thing, no bigger than a hardvoer book, with a ribbon-thin strap, the same purse all the girls carry, as if it’s part of a uniform.) Is this her parent of guardian spaking?

I hear my wife say, “This is her mother.” And then, the bottom dropping out of her voice. “Is she—?”

Notice how the vast scope of the historical event contrasts with the details of the daughter’s purse—all the minutia of a daughter lovingly recalled. The reader doesn’t have to have this explained. One impact informs the other. And the reader grasps the terrible meaning of the two narrative strands: how everything, even the smallest and most ordinary thing, can be blown to smithereens and with such force that it might as well be the end of life and time, complete.

Another example. Ivan Illich was invited to Chicago to speak about public schools. The night before his lecture, he was involved in a discussion of Schindler’s List, a book about a German industrialist who saved a small “list” of Jews from the extermination camps. Illich was tired from his travels and “teetered on the divide between reason and dream.” He found himself thinking about a Chicago School principal in terms of Schindler. About Schindler, he wondered, “Why did Schindler do what he did? What gave him the stamina? the motivation? Did he act out of moral outrage? Or did he enjoy the gamble, deriving immense pleasure by outwitting the bureaucratic monster? Had this little German somehow fallen in love with Jewishness? Or, rather, was it guilt that drove him?” Then he woke up a bit more and remembered,

I had come to Chicago to speak about schools, not camps. My theme was educational crippling, not Nazi murder. But I found myself unable to distinguish between Oskar Schindler in his factory in Cracow, and Doc Thomas MacDonald in Chicago's Goudy Elementary, where he is the principal. I know Doc as indirectly as Schindler, I know him only from the Chicago Tribune, but I cannot forget him. And for some weeks now I have asked myself: Why does he stay on the job? What gives him the courage? …

By confessing to my daydream [that linked public schools and extermination camps], I know that I cannot but call for rebuttal. I know what I do. In a sense, there is no way out of comparing the class of historical events that go under the name of Hiroshima, Pol Pot Cambodia, Armenian Massacre, Nazi Holocaust, ABC-stocks or human gene-line engineering on one hand, and, on the other, the treatment meted out to people in our schoolrooms, hospital wards, prisons, slums, or welfare shelters. But, in another sense, both kinds of horrors are manifestations of the same epochal spirit. We need the courage and the discipline of heart and mind to let these two classes of phenomena interpret each other.

Illich pushes together two historical phenomena so that he can understand better where he is in history and in space.

So, find your places in time or on earth, and allow them to play out and into each other. As the writer, you will be guided by your obligation to get the details just right. And the reader will follow you, back and forth, to and fro, in an act of trust and as an actor in the drama, putting the pieces together.

Note: this piece can be fiction, non-fiction, or creative-non-fiction. You may enjoy doing research, either in the library or in conversations with friends and relatives.

T.C. Boyle’s story, “Chicxulub,” is in Tooth and Claw, which is on reserve in the library.

Make sure to have your work reviewed.