Hi-Fidelity Recording

From fifties

Contents |

[edit] High Fidelity

High fidelity or "hi-fi" reproduction is a term used by home stereo listeners and home audio enthusiasts (audiophiles) to refer to high-quality reproduction of sound or images that is very faithful to the original master recording. High fidelity equipment has minimal or unnoticeable amounts of noise and distortion and an accurate frequency response as set out in 1973 by the German Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN) standard DIN 45500. The term was most widely used in this strict sense in the 1950s and 1960s; in subsequent decades, the term was applied more loosely to any mid-level stereo system. In the 2000s, the term "hi-fi" for expensive high quality home audio electronics was largely replaced with the term "high-end audio".

After World War II, several innovations created the conditions for a major improvement of home-audio quality:

- Reel-to-reel audio tape recording, based on technology found in Germany after the war, helped musical artists such as Bing Crosby make and distribute recordings with better fidelity.

- The advent of the 33⅓ RPM Long Play (LP) microgroove vinyl record, with low surface noise and quantitatively-specified equalization curves. Classical music fans, who were opinion leaders in the audio market quickly adopted LPs because, unlike with older records, most classical works would fit on a single LP.

- FM radio, with wider audio bandwidth and less susceptibility to signal interference and fading than AM radio.

- Better amplifier designs, with more attention to frequency response and much higher power output capability, allowing audio peaks to be reproduced without distortion.

In the 1950s, the term high fidelity began to be used by audio manufacturers as a marketing term to describe records and equipment which were intended to provide faithful sound reproduction. While some consumers simply interpreted high fidelity as fancy and expensive equipment, many found the difference in quality between "hi-fi" and the then standard AM radios and 78 RPM records readily apparent and bought 33 LPs, such as RCA's New Orthophonics and London's ffrrs, and high-fidelity phonographs. Audiophiles paid attention to technical characteristics and bought individual components, such as separate turntables, radio tuners, preamplifiers, power amplifiers and loudspeakers. Some enthusiasts assembled their own loudspeaker systems. In the 1950s, hi-fi became a generic term, to some extent displacing "phonograph" and "record player". Rather than "playing a record on the phonograph", people would "play it on the hi-fi".

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the development of the Westrex single-groove stereophonic record led to the next wave of home-audio improvement, and in common parlance, stereo displaced hi-fi. Records were now played on a stereo. In the world of the audiophile, however, high fidelity continued and continues to refer to the goal of highly-accurate sound reproduction and to the technological resources available for approaching that goal.

High-end audio can refer to the build quality of the components, but more specifically, refers to the ability to reproduce a recording with the highest fidelity to the original performance that has been committed to the recording.

Typical qualitative attributes that are scaled by audiophile publications and experts are:

- accuracy vs. warmth

- tonal color vs. speed

- timbre

- size of sound stage vs. depth (spatial origins)

- clarity

- pace

- timing

A theoretically perfect audio system would create the illusion of the listener being present in the performance venue and with the musical performers performing on stage. There would be no sonic signature that imparts any clue as to the fact that the performance is a playback of a recording instead of witnessing a live performance given by the actual musicians in the particular performance venue.

[edit] History

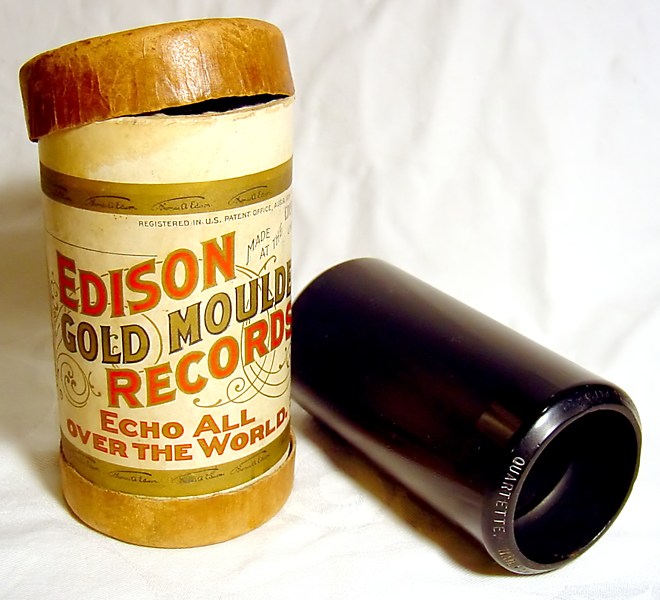

[edit] Phonograph cylinder

The first practical sound recording and reproduction device was the mechanical phonograph cylinder, invented by Thomas Edison in 1877 and patented in 1878. The invention soon spread across the globe and over the next two decades the commercial recording, distribution and sale of sound recordings became a growing new international industry, with the most popular titles selling millions of units by the early 1900s. The development of mass-production techniques enabled cylinder recordings to become a major new consumer item in industrial countries and the cylinder was the main consumer format from the late 1880s until around 1910.

[edit] Gramophone Disc

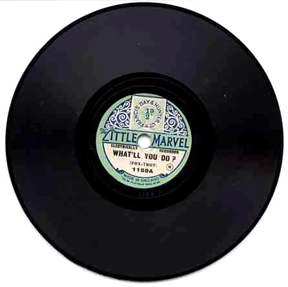

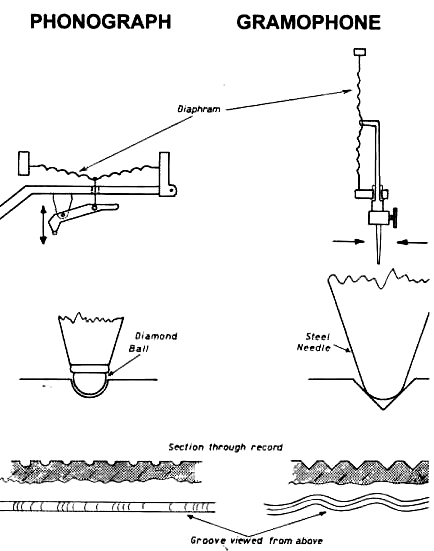

The next major technical development was the invention of the gramophone disc, generally credited to Emile Berliner and commercially introduced in the United States in 1889.

Discs were easier to manufacture, transport and store, and they had the additional benefit of being louder (marginally) than cylinders, which by necessity, were single-sided. Sales of the Gramophone record overtook the cylinder ca. 1910, and by the end of World War I the disc had become the dominant commercial recording format. In various permutations, the audio disc format became the primary medium for consumer sound recordings until the end of the 20th century, and the double-sided 78 rpm shellac disc was the standard consumer music format from the early 1910s to the late 1950s.

Although there was no universally accepted speed, and various companies offered discs that played at several different speeds, the major recording companies eventually settled on a de facto industry standard of nominally 78 revolutions per minute, though the actual speed differed between America and the rest of the world. The specified speed was 78.26 rpm in America and 77.92 rpm throughout the rest of the world (this was related to the speed of a mains-driven synchronous motor). The nominal speed of the disc format gave rise to its common nickname, the "seventy-eight" (though not until other speeds had become available).

Discs were made of shellac or similar brittle plastic like materials, played with needles made from a variety of materials including mild steel, thorn and even sapphire. Discs had a distinctly limited playing life which was heavily dependent on how they were reproduced.

The earlier, purely acoustic methods of recording had limited sensitivity and frequency range. Mid-frequency range notes could be recorded but very low and very high frequencies could not. Instruments such as the violin transferred poorly to disc; however this was partially solved by retrofitting a conical horn to the sound box of the violin. The horn was no longer required once electrical recording was developed.

The vinyl microgroove record was introduced in the late 1940s, and the two main vinyl formats -- the 7-inch single turning at 45 rpm and the 12-inch LP (long-playing) record turning at 33 1/3 rpm -- had totally replaced the 78 rpm shellac disc by the end of the 1950s. Vinyl offered improved performance, both in stamping and in playback, and came to be generally played with polished diamond styli, and when played properly (precise tracking weight, etc.) offered longer life. Vinyl records were, over-optimistically, advertised as "unbreakable". They were not, but were much less brittle and breakable than shellac. Nearly all were tinted black, but some were colored, as red, swirled, translucent, etc.

Booms in record sales returned after World War II as standards changed from 78s to vinyl long play records, which could contain an entire symphony and 45s which usually contained one hit popularized on the radio, plus another song on the back or "flip" side. An "extended play" version of the 45 was also available, designated 45 EP, which provided capacity for longer selections, or two regular-length songs per side.

By the 1960s, inexpensive portable record players and record changers which played stacks of records in wooden console cabinets were popular, usually with heavy and crude tone arms. Even drug stores stocked 45 rpm records at their front counters. Rock music played on 45s became the soundtrack to the 1960s as people bought the same songs that were played free of charge on the radio. Some record players were even tried in automobiles, but were quickly displaced by 8-track and cassette tapes.

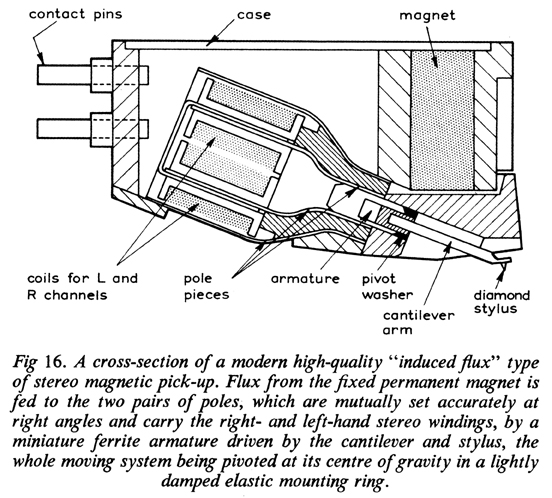

High fidelity made great advances during the 1970s, as turntables became very precise instruments with belt or direct drive, jewel-balanced tonearms, some with electronically controlled linear tracking and magnetic cartridges. Some cartridges had frequency response above 30 kHz for use with CD-4 quadraphonic 4 channel sound. A high fidelity component system which cost under $1000 could do a very good job of reproducing very accurate frequency response across the human audible spectrum from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz with a $200 turntable which would typically have less than .05% wow and flutter and very low rumble (low frequency noise). A well-maintained record would have very little surface noise, though it was difficult to keep records completely free from scratches, which produced popping noises.

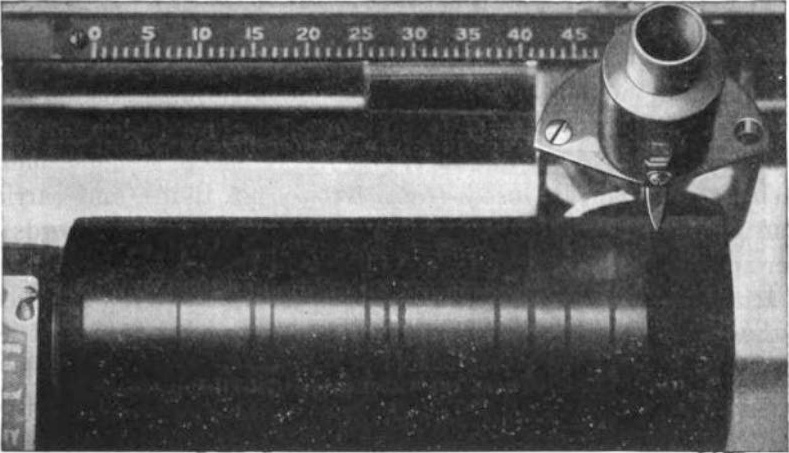

[edit] Stylus

The stylus is the needle used to play back sound on the phonographic records. The harder the material used for records, the harder the stylus has to be. The styli for playing vinyl records are made out of sapphire or diamond. It is the crucial part of the cartridge as this is the part that rides on the record groove. In most cartridges particularly moving magnets, the stylus is user replaceable, hence your interest. In moving coil designs, the whole cartridge needs to be replaced or sent back to the factory for re-tipping.

The stylus unit is actually made up of three to four parts. There is the (1) stylus itself which is made of a hard material typically diamond. It is mounted on the end of a short arm called a (2) cantilever that can pivot as the stylus tracks and is moved by the record grooves. The cantilever is fastened to a (3) grip, an appropriate term for a contraption that you hold to insert the stylus unit into the cartridge. A few manufacturers include a (4) record brush along with their stylus.

Diamond needles last longer, sapphire needles wear out sooner. Sometimes it is possible to provide a sapphire needle at the lowest cost for replacement needles, but generally Diamond needles are always used in modern turntables. There are records with combinations of these sizes and speeds, such as 45 RPM 12 inch records, and there are also records recorded at the slowest of standard speeds which is 16 RPM, but outside of custom transcription recordings, virtually all commercially produced records require only one of two standard needle sizes for playback.

Both 33 1/3 RPM and 45 RPM Records use the same needle for playback, you sometimes see early records of this type with the "Microgroove" designation, which was a way to alert the user that they were not 78's but had a smaller groove size.

78 RPM Records require a different size of needle for playback, it is wider than the needle used for 33/45 RPM Records.

If you attempt to use a needle intended for 78 RPM records on 33/45 Records it often will skim across the surface because it is too wide to fit into the narrow grooves of the LP "Microgroove" records.

And if you attempt to play a 78 with a LP needle it goes straight to the bottom of the groove just barely picking up the groove wall where the music is recorded, mostly playing back the dirt at the bottom of the groove. If you hear someone playing a 78 record and most of what you hear is hiss and noise with a little thin sounding music in the background, they are using an LP needle to play a 78 record. With the right needle 78's can sound pretty good. A lot better than most people would expect from such an "old" technology.

[edit] Amplifiers

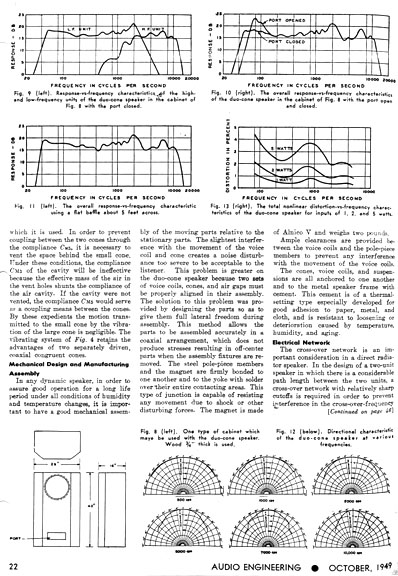

A well designed amplifier must provide means for selecting, controlling and equalizing signals from any desired source. These normally include standard types of phonograph pick-ups, microphones, tuners, compact disc players, or a tape-recorder relay outlet. Unlike most signals, which can b eassumed to originate with a nominallyflat frequency response, the majority of modern high-quality magnetic gramophone pick-ups generate an output with a response related to the "constant amplitude" disc recording characteristic, except in so far as this i smodified by their own intneral mechaniscm.

Modern moving-magnet, moving-coil and variable reluctance pick-ups give an output substantially proportional to frequency for discs recorded strictly according to this characteristic, which is now a generally accepted international standard (BSI, RIAA etc). The input stages of amplifiers are thus generally designed to compensate for this curve when switched to normal phono inputs. However, certain inputs are more conveniently designed so as to give a natural compensation for th standard recording characteristic and thus require a near-flat input amplifier position.

Commercial stereo amplifiers, also known as "receivers", are provieded with accurately matched and ganged controls for switching, bass, treble, volume, etc. In addition a balance control is provided giving a fine control of the relative gain between the two channels.

[edit] Loudspeakers

[edit] Sound to "Signal" Transformation

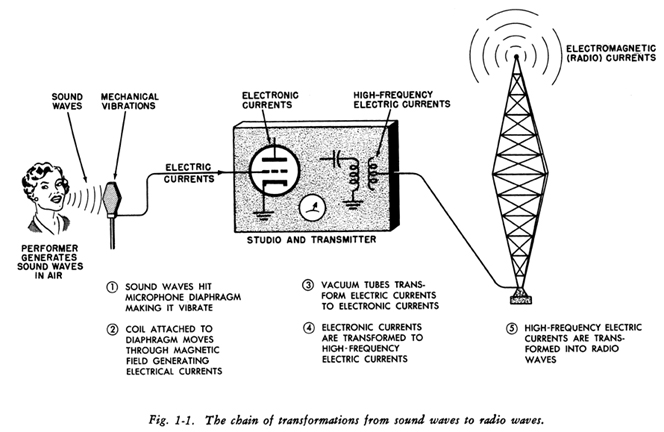

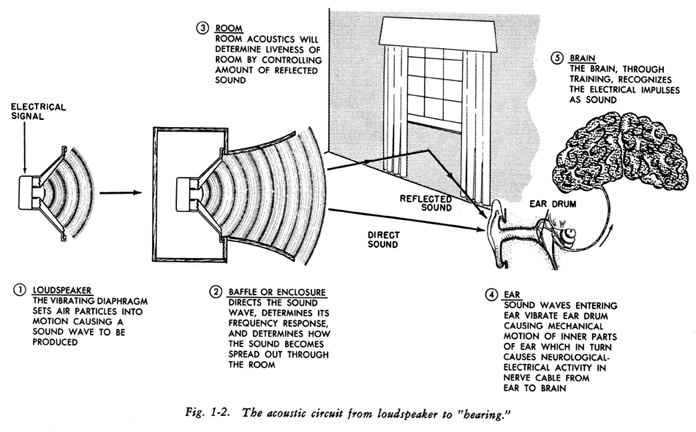

The loudspeaker is the device that produces sound from a pure electrical signal. This signal itself has gone through many subsidiary chains before reaching the terminals of the loudspeaker. In these subsidiary chains there have been many different kinds of link (acoustical and mechanical, electrical, electronic, and electromagnetic).

In even the simplest of broadcast linkages between the original performer in the broadcast studio and your radio antenna, there are involved at least these five distinctly different transformations of the original program. The voice of the singer has vibrated the air particles, setting up a wave motion in the air in the studio; this wave motion in air is acoustical in nature. The traveling acoustic wave impinges on the sensitive microphone, whose ribbon or diaphragm in turn is forced to vibrate in synchronism with the acoustic wave flowing past it. The delicately suspended diaphragm will move back and forth, riding the sound wave just as a cork will bob up and down in a water wave. Here is the first transformation, acoustical energy has been changed to mechanical energy. The vibrating diaphragm with a small coil attached to it, vibrating in a magnetic field, generates an electrical current in its coil, just as the rotating armature in an automobile generator produces a charging current.

This then is the 2nd transformation, the change from vibrating mechanical energy to electrical "vibrations". The electrical current or voltage thus generated operates upon a whole chain of amplifiers utilizing vacuum tubes, which convert the electrical signal to an electronic signal (transformation number 3). Other vacuum tubes in the transmitter impress these signals onto high-frequency electric (radio) currents (transformation number 4). At the final stages of the radio transmitter the fifth transformation takes place: the electronic signal is converted to an even different type of signal, an electromagnetic wave motion, which then travels to your antenna with the speed of light!

[edit] "Signal" to Sound Transformation

Without making things to incredibly complicated (yea right!), the next step is that an electrical signal finally finds its way to the terminals of your loudspeaker, and this signal is in some general way representative of the original sound in the studio. The signal the loudspeaker sees is purely electrical in nature. This signal "vibrating" electically in accordance with the original signal, in turn causes the loudspeaker "motor" to vibrate in synchronism with it.

[edit] Prime Source of Sound

Nothing in nature works by itself without affecting something else; action and reaction are synonymous in the world of physical reality. The loudspeaker is a real physical object and it produces very real airborne sound waves. You cannot feel these sound waves under ordinary conditions, but you can feel the source that gives them life. It is often very easy to see the loudspeaker vibrations as well as feel them. When the loudspeaker is reproducing low frequencies or moderate intensities, the diaphragm may be clearly seen to be moving back and forth in its housing.

What is there for the diaphragm to react with? Quite simply, the air. It is always in contact with the loudspeaker. It always presents a definite physical load, as real as the weight of your finger, which the diaphragm must cause to vibrate.

This is a dark curiosity; in all those apocalyptic future films where there is no air and everyone lives with a suit...will we be able to hear music without air???

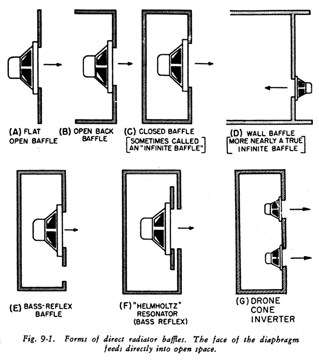

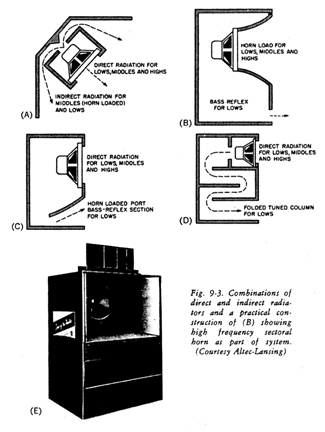

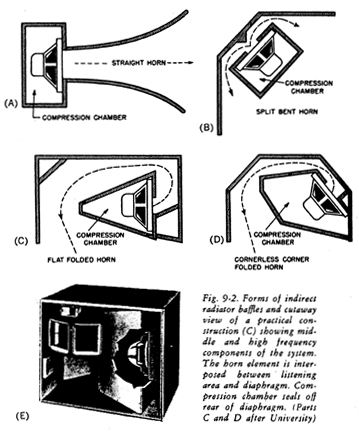

[edit] Enclosures

An essential part of any loudspeaker system is the enclosure in the which the loudspeaker is to be used. An enclosure for a loudspeaker is often called a baffle. The prime purpose of any enclosure is to provide the proper acoustic circuit for the loudspeaker to work with, so that maximum efficiency and best performance may be obtained from the combination. In an effort to provide this acoustic circuit, the sound coming from the loudspeaker is routed into certain paths and prevented from going into other paths by blank walls put in its way.

The term "baffle" as used in a technical sense connotes a means of routing the sound energy. The choice of the proper enclosure or baffle for a loudspeaker system is governed by several factors. These factors are these speaker size, the performance range expected from the speaker-enclosure combination, and the manner in which the speaker is to be operated.

[edit] Singles

The most common form of the vinyl single is the 45, the name for which is derived from its play speed, 45 rpm. The standard diameter of a 45 is 7".

The 7" 45 rpm record was introduced in 1949 by RCA as a smaller, more durable and higher-fidelity replacement for the 78 rpm shellac discs. The first 45 rpm records were monaural, with recordings on both sides of the disc. As stereo recordings became popular in the 1960s, almost all 45 rpm records were produced in stereo by the early 1970s.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, 45 rpm–only players that lacked speakers and plugged into a jack on the back of a radio were widely available. Eventually, they were replaced by the three–speed record player.

From the mid-1950s through the 1960s, in the U.S. the common home "record player" or "stereo" (after the introduction of stereo recording) would typically have had these features: a three- or four-speed player (78, 45, 33 1/3, and sometimes 16 2/3 rpm); with changer, a tall spindle that would hold several records and automatically drop a new record on top of the previous one when it had finished playing, a combination cartridge with both 78 and microgroove styluses and a way to flip between the two; and some kind of adapter for playing the 45s with their larger center hole. The adapter could be a small solid circle that fit onto the bottom of the spindle (meaning only one 45 could be played at a time) or a larger adaptor that fit over the entire spindle, permitting a stack of 45s to be played.

RCA 45s were also adapted to the smaller spindle of an LP player with a plastic snap-in insert known as a "spider". These inserts, commissioned by RCA president David Sarnoff and invented by Thomas Hutchison, were prevalent starting in the 1960s, selling in the tens of millions per year during the 45's heyday.

Although 7" remained the standard size for vinyl singles, 12" singles were introduced for use by DJs in discos in the 1970s. The longer playing time of these singles allowed the inclusion of extended dance mixes of tracks. The 12" single is still considered a standard format for dance music, though its popularity has declined in recent years.

[edit] Custom Vinyl

These days, records can come in all shapes and sizes with advanced pressing units and lacquer color.

You can even get picture discs!

[edit] Links

A Dictionary of Home Entertainment Terms

Earliest Recordings by Thomas Edison

[edit] References

- Gaylord, M. L. HI-FI FOR THE ENTHUSIAST

Pennsylvania, TAB Books, 1972

- Cohen, Abraham B. HI-FI LOUDSPEAKERS AND ENCLOSURES

New York, Hayden Book Co., 1968 2nd Ed.

- Yoder, Andrew R. HOME AUDIO : CHOOSING, MAINTAINING, AND REPAIRING YOUR AUDIO SYSTEM

New York, McGraw Hill, 1998

- Davidson, Homer L. TROUBLESHOOTING AND REPAIRING AUDIO EQUIPMENT

New York, TAB Books, 1996, 3rd Ed.

- Harley, Robert The Complete Guide to High-End Audio

New York, Acapella Publishing, 1998, 2nd Ed.