The Origins of Independent Film

From mediaartiststudio

Contents |

[edit] The Independents vs. the MPPC

[edit] The Edison Trust

Independent film can be traced back to the 1900s, which began in response to the control of the Motion Picture Patents Company or "Edison Trust."

The MPPC was founded in December 1908, and was a trust of the major film companies of the era (Edison, Biograph, Vitagraph, Essanay, Selig, Lubin, Kalem, American Star, and American Pathé) along with the leading film distributor George Kleine, and Eastman Kodak, the largest supplier of film stock.

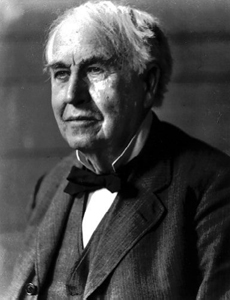

For years, Thomas Edison controlled many major patents relating to motion pictures, the most substantial of which being a patent on raw film. Effectively, this made independent filmmaking (anything made outside the control of the MPPC) illegal, and the MPPC ruthlessly enforced its patents to bring lawsuits against independent filmmakers. Because of this effective filmmaking dictatorship, many filmmakers built their own cameras, moved away from Edison's primary base of operations in New Jersey, and took refuge in Southern California, where the distance from the MPPC made it much more difficult for Edison to enforce his patents.

[edit] The Fall of the MPPC

The so-called "Independents" quickly began to rise in popularity amongst audiences. Beginning around 1910, the Independents starting crediting their actors, which was not allowed under the strict rules of the films created under the MPPC. The MPPC had decided against such a process because they had realized that by making their actors famous, they would have to pay them more. Ironically, audience desire to see work that had the "star power" presence that actors gave to independent films ended up recouping and profiting from the investments required to hire them. While the Independents flourished due to the rising stars they had cast, Edison staunchly held to his opinion that only his own name would matter to the consumers. Edison's opinion was soon proved otherwise, as the Independents continued to succeed at creating bankable film stars, while audiences soon lost interest in MPPC films with unnameable actors.

A major blow to the MPPC arose from a ruling in 1912 when the Supreme Court canceled the MPPC patent on raw film, preventing Edison from continuing his relentless but increasingly unsuccessful pursuits against independent filmmakers. More seriously, in 1915, the Supreme Court canceled all MPPC patents. Two years later, the MPPC's oligopoly ended, and the groundwork laid out by the Independents turned into the classical Hollywood studio system.

[edit] The Second Wave of Independent Filmmaking

[edit] United Artists

When this system became the main driving force behind filmmaking in America, once again filmmakers sought independence. The first independent studio, United Artists, was formed by Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and D. W. Griffith with the intention of better controlling their own work and securing their futures.

The first film distributed under United Artists was Broken Blossoms or The Yellow Man and the Girl, directed by D. W. Griffith, originally produced for Adolph Zukor's Artcraft company (a subsidiary of Paramount Pictures). Upon the completiton of the film, Zukor was outraged, proclaiming the film to be terrible and unsellable, as many of the major characters die. Infuriated, Griffith left the producer's office and returned the following day with $250,000 in cash and bought back the film from Zukor. Broken Blossoms thus became the first film released by United Artists, and was a remarkable critical and financial success.

[edit] The Society of Independent Motion Picture Producers

In 1941, some of the members of United Artists joined up with other notable celebrities of the film industry (including Walt Disney, Orson Welles, and Samuel Goldwyn) founded the Society of Independent Motion Picture Producers, which aimed to preserve the rights of independent producers in an industry overwhelmingly controlled by the studio system. SIMPP fought to end the monopolistic practices by the five major Hollywood studios which controlled the production, distribution, and exhibition of films.

In 1948, the SIMPP succeeded against Hollywood when the Supreme Court's "Paramount Decision" forced Hollywood studios to sell their theater chains, thus ending certain anti-competitive practices. This act ended the studio system of the Golden Age of Hollywood, and by 1958, SIMPP closed its offices due to having succeeded in accomplishing its goals.

[edit] A Brief History of Independent Animation

The origins of animation in film are as old as the advent of motion pictures themselves, as various animation devices such as the phenakistoscope, praxinoscope, and the flip book existed long before film. When the film camera was invented, many took advantage of the benefits of animated films over physical animated media, such as potentially much longer running times, a longer lifespan, and easier distribution.

Many contributors to the early motion picture animation movement were working independently. Notable examples include Georges Méliès who utilized stop-motion animation techniques in many of his live-action films, J. Stuart Blackton's The Enchanted Drawing (a primarily live-action piece with animated elements) and Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (regarded by many to be the first "true" animated film), and Émile Cohl, who was inspired by Blackton and made Fantasmagorie, which is considered to be the first fully animated film with no live-action elements.

[edit] References

- "La-La Land: The Origins" Peter Edidin. New York Times. New York, N.Y.: Aug 21, 2005

- Schickel, Richard. "D.W. Griffith: an American Film Life." New York: Proscenium Publishers Inc, 1984

- Donald Crafton; Emile Cohl, Caricature, and Film; Princeton Press, 1990

Return to Independent Media Artists