Jim Henson: Children's Media Pioneer

From mediaartiststudio

"Life's like a movie, write your own ending. Keep believing, keep pretending."

"My hope is to leave the world a little better for having been there."

"The most sophisticated people I know - inside they are all children."

-Jim Henson

Contents |

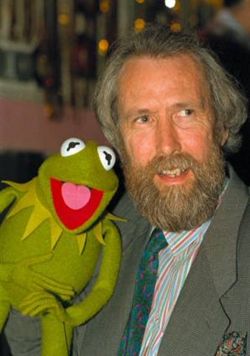

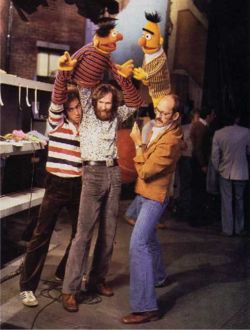

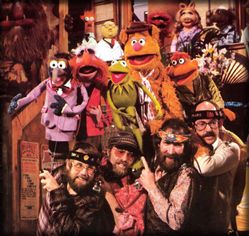

[edit] Pioneer of Puppetry

During his time on Sesame Street and The Muppet Show, Jim Henson primarily worked with basic hand and rod puppets. With one hand, the puppeteer would manipulate the character’s mouth. The puppet’s arm had a rod extending from it, which was operated by the puppeteer’s other hand. Perfect examples of this type of puppet would include Kermit the Frog and Guy Smiley, both of which were performed by Henson. These puppets, while simple, were quite effective in conveying basic gestures and emotions. Henson began to explore the possibilities of a puppet with the ability to move more naturally, and express subtler emotions.

Henson, overseeing a host of puppet designers, jewelry makers, robotics experts, and technical wizards such as Faz Fazakas, would completely redefine the parameters of puppetry, beginning with The Dark Crystal. Co-Directed with Frank Oz, Henson’s feature film was to be the first of its kind: a live action film with no human actors seen on screen. Henson worked with illustrator Brian Froud to conceive a completely new world, filled with inhabitants of all shapes and sizes. With the use of remote control and cables, Henson’s crew had discovered a way to extract more “authentic” performances from its puppet stars. Many characters faces were controlled remotely to express emotion. The technical feats of The Dark Crystal cemented Henson and his crew in puppet history, and in so doing, created a new field of puppet design known as “animatronics“.

With Labyrinth, Jim Henson’s Creature Shop would continue to expand their experiments most in their second-lead character, Hoggle. Hoggle was performed by five people: one performer wore Hoggle’s suit to act as his body, while the other four manipulated the eighteen motors located in his head to control his facial movements. This proved to be challenging for the team, who had to rehearse to the point where they could convincingly create expressions while working in total sync. Through Henson’s vision, a fifteen-foot puppet, Humungous, was also constructed for the film. A towering menace made of polyurethane foam, Humungous was controlled by one single puppeteer, who wore a suit covered in censors that would remotely signal the puppet to mimic his movements. The second largest creature in the film was Ludo, the lovable beast, was performed by one puppeteer in a suit (though there were two performers who took turns). The suit, weighing over seventy pounds, contained two monitors inside, which transmitted images captured by a camera hidden in Ludo’s right horn.

Following Labyrinth, Jim Henson used his new international children’s program, Fraggle Rock, to showcase his designers’ latest advancements in puppetry. Faz Fazakas continued to improve on remote control manipulation with the Doozers, the smallest inhabitants of Fraggle Rock. With a single Doozer, one performer could manipulate both its mouth and body motions using a mitt-shaped glove. Adding another controller to work the joysticks on a miniature vehicle could empower the Doozers to cruise around their constructions with ease. The Gorgs were modeled after Ludo’s design, but with mouths that were remotely controlled by their voice over counterparts during taping. The Fraggles themselves were simple hand and rod puppets, while more elaborate characters of all shapes and styles were continually added to the mix over the show’s four year run.

[edit] Pioneer of Children's Television

Sesame Street is undeniably the most innovative children’s show of its generation, or any. With more than 4,100 episodes under its belt, Sesame Street marked many firsts in the genre of children’s television. Henson’s Muppets helped to bring basic arithmetic, reading, comprehension, and classification skills to preschoolers and inner city children beginning in 1969. With Joan Ganz Cooney, Henson worked to establish a program that would equip its young viewers with basic learning skills, as well as a sense of connection within families, friends, and community. The show also dared to go where most children’s shows would not, directly tackling issues like the death of store owner, Mr. Hooper, with sensitivity to its audience. To address the September 11 attacks, an episode in which Elmo witnesses a grease fire at Hooper’s store was meant to restore comfort in its young viewers through examining fear. The episode also gave a healthy nod to the New York City Fire Department, who arrived to put out the fire, and whom Elmo gratefully thanked. Another landmark episode included Snuffleupagus at last appearing, despite the neighborhood’s belief that he was merely Big Bird’s imaginary friend. The show’s writers decided to show Snuffy as real in order to encourage children to confess stories of abuse to trusted adults. Child therapists discovered that children were less likely to reveal cases of abuse out of fear that their stories would be too fantastical -- to combat this, writers felt that revealing Snuffy, who himself is fantastical, would assist in creating that trust.

While Sesame Street worked at targeting urban areas, Fraggle Rock worked to reach an international audience. The first of its kind, Fraggle Rock was Henson’s attempt to “stop war in the world”, through the conceptualization of a world in ultimate symbiosis. Henson’s vision of a global community surfaced in episodes addressing prejudice, spirituality, environment, and social conflict. To understand this symbiosis, one must look at the race of characters in Fraggle Rock:

Fraggles: playful, subterranean inhabitants whose priorities include music, laughter, games, contests, radish hoarding and the mass consumption of Doozer buildings.

Doozers: small, construction worker-like builders who erect crystalline structures throughout the Rock, which are subsequently eaten by any Fraggle passing by.

Gorgs: a royal family of large oafs, who maintain a garden outside their castle that grows plenty of produce -- including radishes. A Fraggle’s worst enemy.

Doc and Sprocket: an inventor and his dog, who live in what fraggles refer to as “outer space”, but what we could call a workshop. The workshop contains a hole in the wall, which the Fraggles can use to access our world.

One example of the symbiosis of Henson’s characters is that of their relationships to the radish. The Gorgs grow radishes, which are then stolen and eaten by Fraggles, and are used by the Doozers to create material for their buildings, which are also eaten by Fraggles, and with less radishes in the garden, Gorgs are forced to grow more. All groups in this dynamic depend on one another, and are unified by their shared need for radishes.

In an interview, Henson described the show’s intent:

“What the show is really about is people getting along with other people, and understanding the delicate balance of the natural world. These are topics that can be dealt with in a symbolic way, which is what puppets basically do all the time. The world… will have its own natural balances, although these will be rather insane. But still we will make the point that everything affects everything else, and that there is a beauty and harmony of life to be appreciated.”

In both of these television shows, young viewers can get a glimpse of Henson’s vision of an ideal future, filled with tolerance, community, and respect for every living thing, big or small. Both Sesame Street and Fraggle Rock redefined the parameters of a children’s program, tapping into previously undiscovered modes of communicating to children about sophisticated, and sometimes sensitive, ideas.

[edit] Pioneer of Children's Film

While The Muppet Movie is widely recognized by fans as his first film, this can only be true if referencing the Muppets specifically. In truth, Henson had been making short films during the 1960s, exploring abstract and experimental storytelling with works like The Cube and Timepiece, which was nominated for an Academy Award. These crude films were only the beginning of an impressive foray into cinema for Henson that would span over ten years.

When examining Jim Henson’s work in film, the technical and special effects achievements are not hard to identify. His work with The Creature Shop marked the beginning of animatronics, a field which is dominated by the shop to this day. But often, the achievements he made in thematic content are overlooked, which is easy to do given the shear impressiveness of his strides in puppetry. Nonetheless, a closer look at a film such as The Dark Crystal offers some insight to the mind of the man who helped to make it.

When initially conceptualizing The Dark Crystal, Jim Henson wanted to create a pantheistic world where objects could become animate and all forms of life would be interconnected. To this end, Henson worked with illustrator Brian Froud to create a race of characters known as the urSkeks, who, as a prologue to the story, become divided into two new races known as the Mystics and the Skeksis. The Mystics, as their name would suggest, are mystical, earthy, monk-like creatures who preserve the old world through ritual and practice. The Skeksis, on the other hand, have ravished the land and are gnarled, power hungry, and deeply at war with the natural world, as well as its inhabitants. While the Mystics govern themselves with a collective interest in mind, the Skeksis battle with one another to assume control at any opportunity. Despite these differences, Henson depicts their interconnectedness in the most literal way possible: when a Mystic is injured or dies, so does its Skeksis counterpart, and vice versa. Henson chose to approach the concept of interconnectedness in the most obvious way he could, to ensure the message would reach children. In creating these characters that are two halves of the same whole, he is tapping into Eastern notions of yin and yang, of light and dark, and pointing out their dependence on one another to exist.

Jim Henson also explored some heavy themes in the film Labyrinth, Henson’s second film in the fantasy realm. The film’s heroine, Sarah, is a young girl teetering on the brink of adulthood, but who still clings to the fantasy and make-believe her childhood always promised. When faced with the task of caring for her baby brother, Sarah wishes him to be taken away by goblins. The wish comes true, and ultimately it is up to Sarah to navigate a treacherous labyrinth to save her brother. Along the way, Sarah is faced with many challenges, both physical and psychological. One of those challenges takes form in Jareth, the Goblin King, who promises to grant her every wish so long as she leave her brother in Jareth’s charge.

The character Sarah is meant to embody the uncertainty we all face during the shift from pre-pubescence to full adulthood, and the obstacles she encounters on her journey are meant to teach her how to best balance the girl she is and the woman she is becoming. In one scene, Sarah is transported to a masquerade ball existing inside a bubble. What Sarah finds there is a crowd of adults, dressed in lavish costumes and exaggerated goblin masks, dancing with certainty and precision. She herself is dressed in a white gown, symbolic of her virginal status no doubt, and feels lost until she recognizes Jareth, who then takes her hand and leads her through the motions of the dance. The dance itself, which the adults do with ease, is not particularly uniform or complex for Sarah to manage, but it implies a recreation with which the adults are confident and Sarah is insecure. This scene seems to represent Sarah’s curiosity with the world of adults, though her fear and inexperience eventually get the best of her, and she escapes the bubble, shattering it to break free.

In all, Henson’s films for children would continue to address, directly and indirectly, the trials all adolescents will face. Henson felt it important to empower his young viewers with the ability to resolve conflict, both personal and intrapersonal, in an effort to better navigate their worlds. Henson ensured that his films contained these concepts, and varied his approach to suit the subject, but all the while created movies that children could rely on for lessons in life – particularly the lessons that parents may be reluctant to address themselves. Never preachy or insistent, Henson devised films that would encourage questioning, discussion, and above all else, understanding.

[edit] Early Experimental Work

"The Cube" - 1969 http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-6203080879952576646

"Time Piece - 1965 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TfULBej_qRc

[edit] Links

http://www.muppetcentral.com

http://muppet.wikia.com/wiki/Muppet_Wiki

http://www.sesameworkshop.org/home

http://users.bestweb.net/~foosie/henson.htm

http://www.darkcrystalthemovie.com

http://www.fragglerocker.com/

http://www.filmfreakcentral.net/dvdreviews/storyteller.htm

http://www.creatureshop.com/about_history.php

[edit] Sources

^ a b "The Man Behind the Frog", TIME (1978-12-25). Retrieved on 25 Nov. 2008.

^ a b Skow, John (1978-12-25). "Those Marvelous Muppets", TIME. Retrieved on 25 Nov. 2008.

^ Darnton, Nina (1986-06-27). "Jim Henson's "Labyrinth"", The New York Times. Retrieved on 30 Nov. 2008.

Bacon, Matt. “No Strings Attached: The Inside Story of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop”. New York: Macmillan General Reference, 1997.

Finch, Christopher. “Jim Henson: The Works – The Art, the Magic, the Imagination”. New York: Random House, 1993.