Media

PRECURSORS TO VIDEO ART

-Pop Art

Roy Lichtenstein, Washing Machine

Starting in the mid-late 1950′s, Pop Art dealt with images and motifs related to popular culture and mass production. Pop works often incorporated such social detritus as consumer products, corporate logos and advertising slogans, elevating these elements to the realm of high art for the first time. Pop began a tradition of examining mechanical reproduction through the lens of artistic expression that carried over into the video art of the 60′s. Both movements dealt with the capitalism’s (specifically advertising’s) homogenizing effect on culture in relation the individual.

Andy Warhol, TV$199

-The Happening

Starting in the late-1950′s artists began producing work that did not fit into traditional art formats such as painting and sculpture. These pieces often incorporated live performance, collage and video projection. Artist Allan Kaprow coined the term “happening” to describe work that “was just supposed to happen naturally”. The word stuck and by the 60′s “happening” had become a catch-all term for any event related to the counter-culture.

Allan Kaprow, Yard

EARLY VIDEO SYNTHESIZERS

Artists interested in video during the early 1960′s would have a few years to wait before video recording and playback systems became widely available to the average consumer. Instead, many artists focused on creating works using manipulated video signals with the frame of a TV set. Magnets were applied to screen, cathode ray tubes extracted from sets, circuits rewired, etc. This tradition carried on even after video was introduced to the consumer market, with artists experimenting with modular processing of video signal into the early 70′s. As the video art genre matured, a split began to emerge between artists working in the more representation field of videomaking, and artists producing more impressionistic work with video synths. Much of the technology used to created these video pieces was developed in research facilities or university labs by technicians functioning as both art and science pioneers.

Nam June Paik, a prominent video artist who worked on both sides of the video synth/video art debate, developed this video synthesizer with technitian Shuya Abe and a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation

PORTAPAK

The Sony Portapak revolutionized video production worldwide. The system was available in most electronics stores and came with all the neccesary tools to shoot and view videotape. For the first time ever average people could produce video relitively easily and cheaply. The lead to a huge explosion of the video medium in the late 1960′s. The technology was used for everything from art to revolutionary calls to action.

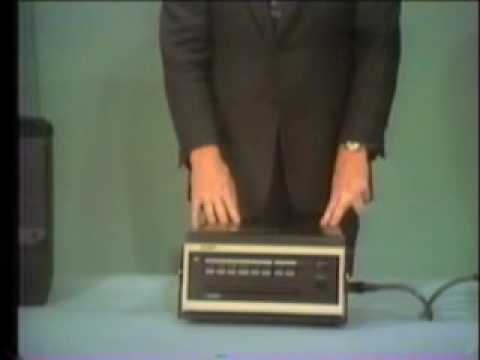

Portapak

A later generation Portapak commercial from the 70′s.

FLUXUS

The Fluxus art movement was one of the first to embrace videos utopian possibilities. One of the main tenets of Fluxus philosophy (such as it exists) is the idea that art can function outside of the normal system of production and distribution present within the capitalist system. Fluxus artists tried to reclaim art for themselves, setting up their own Fluxshops and mailorder businesses to sell their works. This idea hearkens back to Pop Art’s exmination of the idea of multiples, but takes it a step further. In his 60′s era essay on Fluxus, Owen Smith explains Fluxus works in relation to mass production. “The Fluxus works produced in the mid-1960′s, even hte most object based examples…should all be seen snot as art works or even mulitiples, but in their intended context: as publications, albeit quite different from what is traditionally thought of as publication.”

Fluxus video works (or Fluxfilms), were numbered and serialized, released like issues of a comic book or magazine. Fluxus artists saw video as a utilitarian method of disseminating their artistic concepts.

–The titles of Fluxus videos often provide the audience with needed context for the images they are about to see by revealing the work’s structure from the onset. When viewing Fluxflms with their titles in mind, viewers often find long passages more watchable. This is especially true for viewers accustomed to seeing video formatted for television, where shows must constantly endeavor to stimulate the senses in order that they may be eye-catching, even when viewed for a only a split-second. In this video by French Fluxus artist Ben Vautier BKA “Ben”, a long take of what appears to be a body of water with nothing happening registers instead a highly dramatic scene when considered in relation the pieces title, “The Crossing of the Port of Nice by Swimming”. At the beginning of the video the camera watches from across the water as a man jumps into the port, then waits patiently for him as he takes about ten minutes to swim across. One wonders what fate will befall him as he attempts this death-defying physical feat. A single camera view of the entire event builds tension exponentially, leaving the audience with little else to focus on besides the fate of the man. The audience (and the camera) wait with baited breath for the man to emerge from the murky depths and back into frame, which he dutifully does at the end of the piece.

RADICALISM

Just as artists saw video as a populist medium, so too did political radicals of the late-60′s. To them, video was the most effective way to get their rhetoric to the masses. Because the Portapak was so cheap and portable, radicals making so-called “Guerrilla Television” could, for a short time, gather news in the field more effectively than their big studio counterparts.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)