By: Tanya Lynch

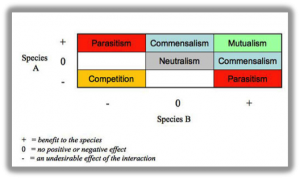

I’m sorry to say, but Science Fiction has lead us astray. Because of television shows like Stargate SG1 and characters like Teal’c (who carries a symbiote Goa’uld) many believe a symbiotic relationship is a relationship in which both parties involved benefit. Alas, this is not always true. In fact, symbiotic simply means a close, prolonged association between two or more different organisms of different species.

There are actually five different types of symbiotic relationships: Parasitism, commensalism, mutualism, neutralism, and competition. Of these, parasitism and mutualism are the most common relationships formed by fungi.

Parasitism is when one species negatively affects the second species in the relationship. A tapeworm can live in a parasitic symbiotic relationship with a cow. The flea is a parasite on the dog. Corn smut, Ustilago maydis, is a prime example of fungal parasitism of corn.

Photos: Corn – Dieter Spears/iStockphoto.com. Corn Smut Spores – APS Press. Fake Facebook status created with www.statusclone.com

Ustilago maydis, creates tumor-like growths mixed within the kernels of corn on the stalk. This fungus turns a cheery yellow ear of corn into a deformed and grey mass. These grey tumor-masses are actually kernels that have been infected by U. maydis and filled with teliospores (a type of reproductive cell). In all but central Mexico, this fungus is considered a bothersome disease, but there it is quite the culinary delicacy (The American Phytopathological Society, 2006).

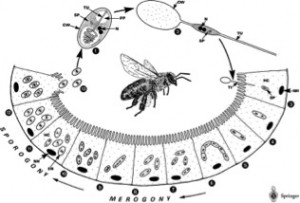

Another example of a parasitic relationship is that of the genus Cordyceps (of which there are many species) and a poor insect host (E.B. Mains, 1958). In this most unfortunate relationship a spore will land in some fashion on a fly and germinate, then stromata (a visible clavate or sometimes branched structure coming out of insect body segments) will form outside of the body. These structures contain the sexual components of the fungi which will release spores when mature. Prior to the release of spores, a particular species in this family, Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, will use neurotoxins to control the movement of ants to climb to the highest part of a grass and bite down to hold on (Harry C. Evans, 2011). This allows the spores to eventually be released in the most prime conditions and location for eventual germination on another unsuspecting ant.

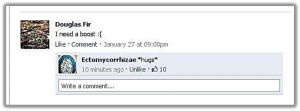

Things are much prettier on the mutualism side of things. The concept of mycorrhizal associations between a fungal partner and a plant partner is the mutualistic symbiosis most commonly referred to when talking about fungi.

Photos: Fir Seedling – Ingrid Barrentine, Northwest Guardian. Microscope Ectomycorrhizae – http://sciweb.nybg.org/science2/hcol/mycorrhizae2.asp.html Fake Facebook status created with www.statusclone.com

In a mycorrhizal partnership a fungal partner will take hold onto the roots of some plant partner and each side will benefit in some way from the association. For instance, the fungus growing around (or in some cases in) the roots of the plant allows for greater surface area of those roots. This greater surface area allows for greater access to water. The fungal partner also helps to shuttle certain nutrients into the plant’s roots (The New York Botanical Garden, 2003). In return, the plant shares some of the carbon created during photosynthesis.

A symbiotic relationship isn’t only a beneficial relationship for both partners. As described above in the fungal examples, there are different types of symbiotic relationships that aren’t positive at all. So before you write your sci-fi novel or television series scripts, be sure to remember these awesome fungi and take into account the diversity of symbiotic relationships and what they look like!

Sources:

The American Phytopathological Society. Common smut of corn. (2006). Retrieved from http://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/intropp/lessons/fungi/Basidiomycetes/Pages/CornSmut.aspx

The New York Botanical Garden. Hidden Partners: Mycorrhizal Fungi and Plants (2003). Retrieved from http://sciweb.nybg.org/science2/hcol/mycorrhizae2.asp.html

E. B. Mains. North American Entomogenous Species of Cordyceps. Mycologia , Vol. 50, No. 2 (Mar. – Apr., 1958) , pp. 169-222

Evans, H. C., Elliot, S., & Hughes, D. Hidden Diversity Behind the Zombie-Ant Fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis: Four New Species Described from Carpenter Ants in Minas Gerais, Brazil (March 2, 2011). Retrieved from http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0017024