Making Toast

Making toast is gathering up fabric, searching for “sewable” ideas, conjuring up images of the large-scale domestic space sculptures of Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, and all the while craving hot buttered toasted bread. Visualized text from Nigel Slater’s Toast: The Story of a Boy’s Hunger and thinking of ways to represent those visions in fabric made the adjective “burned” problematic. Slater’s recollection of his mother’s practice of burning toast kept me from moving forward with the project. But then, while listening to Edmund De Wall’s “Sunday Sermon” Tact on the online site of the U.K.’s The School of Life (http://www.theschooloflife.com/library/videos/edmund-de-waal-on-tact/), I realized that visualizing text is my representation and if fire and fabric just did not go together for me, then so be it.

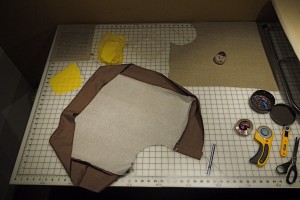

I have a domestic space devoted to sewing projects; the tiny room includes a closet with a fabric collection. All attempts to keep the fabric collection sorted by color and texture have failed, but I was able to find a nice “toasty” bolt of fabric. I have plenty of notions collected after years and years of sewing projects, “ah, that bundle of soft raw wool will work well as the “doughy cushion of white bread” that Slater referred to.

by color and texture have failed, but I was able to find a nice “toasty” bolt of fabric. I have plenty of notions collected after years and years of sewing projects, “ah, that bundle of soft raw wool will work well as the “doughy cushion of white bread” that Slater referred to.

In my effort to weasel out of re-typing the text of Toast for the project, a virtual “light bulb” of the mind blinked on, “this iMac might have speech typing”, and so it did. After figuring out the system, dictated text magically appeared on the screen. The next step was to print the text on fabric, which required a special process of preparing cloth to move through a printer. Of course the oversized piece of toast fabric would not fit the printer, so an 8 ½ by 11 inch piece of the fabric was cut—the problem of fixing it to the larger piece of fabric would have to be solved later.

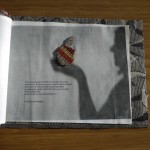

As separate pieces of cotton, linen, thread, and wool became united, the boxy object resembled a pillow more than toast, but cutting away a bite to expose the “doughy cushion” that lies inside the crust offered a suspension of belief that just might work. The project moves on to butter. After a futile attempt to sew yellow rip stop nylon into a block of butter in a shape imagined to be 1960s British butter, I tossed the construction aside and sewed a rectangular stick of butter that looked more realistic. Slater writes “I am nine now and have never seen butter without black bits in it,” but since I have tempered the image of burned toast, my bits in the butter will be brown—stitch, stitch, French knot here, French knot there. I need a butter dish. I need a plate for the toast. Come together visualization of toast!