Copyright Overview

From digmovements

Contents |

Legal Disclaimer

In the new digital age, understanding copyright issues and staying within the bounds of copyright laws are the keys to keeping your wallet in your own pocket and your own good name out of both RL and VL muds. This discussion is provided for information only. It just reflects Jules' understanding. Please don't consider or use this as any kind of legal advice. It's not to be relied on for that, and neither she nor her employer makes any guarantees implied or expressed.

Copyright

"Copyright" is a legal claim that establishes ownership of "original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression," US CODE: Title 17,102. Authorship fixed in a medium of expression means ideas, information, writings, knowledge, images, and other substantive content in stuff ranging from books and articles, to video, audio, paintings, drawings, sculptures, dances, and so on. Basically it means anything capable of being copied - either the tangible form itself or its substantive content lifted into any other form. Copyright means literally that the copyright owner is the only one who has an unrestricted right to copy and use any or all the item in question.

Limits on Copyright

Copyrights in the US were first established in Article 1, Section 8 of the US Constitution. Copyrights were and still are designed to create profit incentives for people to come up with new works and ideas that will lead to social and material progress. A key limit on copyrights, however, is that they expire with time. When a copyright expires, a work enters the "public domain". This is so the copyright owner can profit initially from the exclusive use of his or her works, but in time everyone can make unrestricted use of them so good works and new ideas can spread.

Another key limit is that everyone has rights to copy from and make limited uses of unexpired copyrighted works. For us in Dig Movements, the most pertinent copyright non-owners can have is the right of fair use.

Fair Use

"Fair" uses of copyrighted materials by people other than the copyright owners can be made without the owner's expressed permission. Fair use must be limited in scope and basically intended for not-for-profit educational, analytical, journalistic, or artistic uses including parody and satire. The legal doctrine of fair use has emerged over time from judicial decisions in specific copyright court cases and disputes.

There is a specific idea behind the doctrine of fair use that is very important. Our way of government, especially through the First Amendment, compels that people in our society must have the right to copy and use copyrighted materials in at least some limited ways. This is in order to maintain a commons of ideas that makes and keeps socially redeemable things like education, art, political debate, and a free press possible.

Limits On Fair Use

Still, copyright is legally considered to establish a privately owned "intellectual property". By the Fifth Amendment, any public use of that private property must be fair to the owner. As a doctrine of property law, fair use leaves exclusive right to any and all for-profit or commercial uses of the material entirely in the hands of the copyright owner. Copy rights include the right of owners to buy, sell, license, permit, rent, or prevent any commercial uses of the copyrighted material by any others. Under the current law, copyrights on everything are implied, which means even if something isn't marked as copyrighted, it is unless it specifically says it isn't.

Columbia U's Handy Fair Use Test

Columbia U offers a pretty well structured 4-question process for determining what a fair, unlicensed use of something is. The questions in this process must be askable and answerable in every case.

- What is the intention of the use? Educational, artistic, political, journalistic, or commercial?

- What is the nature of and how original is the copyrighted material? Fiction, nonfiction, creative arts, creative media?

- How much of the work is being excerpted or used? A little, or a lot? Is it substantially altered?

- Could the use take a piece of any commercial action from the copyright owner?

This set of questions comes out of case law decisions courts have made over copyright leading up to now. It provides a good rule of thumb that helps out considerably, but it still often leaves things murky.

Why Are Clear Answers Never Easy?

The problem is that answering these questions often calls for individual or "subjective" judgements. In those cases the fair use decisions at the end rest on materially insupportable conclusions that are subject to arguments and debates that can end up in court. The last question is often the easiest to answer, in part because it requires material considerations, and for that reason it's often the determining one in legal disputes.

Apparently, the copyright laws deliberately establish the determination of fair use to be somewhat vague. This is to ensure that the law remains flexible enough to cover the constitutional principle of keeping things as open for fair use as the politics of the day will allow. It's worth repeating that, for the courts, the most important and often determining factor in a judicial fair use decision is whether or not the use will cut into the commercial market for the copyrighted work or its substantive content.

Why Are They Even Harder On The Web?

On the web, things get really tricky. One act of copying and using of copyrighted material for your own political, educational, artistic, or journalistic use can create a world-wide distribution of the material that goes directly to the commercial uses/piece of the action thing. For students, fair use is pretty expansive. But significant limits are still really real when they bump up against property rights. Just ask Napster. The intentions of the unlicensed copier/user are always considered in fair use court cases, but inadvertence and ignorance of the law provide no excuse.

The FUD Factor

All this being said, unquestioning or "deferential" compliance with fair use rules isn't the answer. It is in the interests of an open society for people to comply with the rules up to their limits and no further. As citizens, we must not let the FUD factor (fear, uncertainty, and dread) dampen or close off our participation in keeping the free flow of information free.

As historians Daniel Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig put it in Digital History: A Guide To Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web:

Copyright law, like history, is subject to conflicting interpretations as well as sharp contention between advocates of the rights of the owners of intellectual property and those seeking to enlarge the public domain. To take a seemingly neutral position of deferential compliance with all copyright “rules” accepts one side in that argument and diminishes the intellectual commons. We believe that a more aggressive assertion of the rights and claims of that commons, when followed sensibly, does not entail excessive risk.

Getting stung over copyright can cost you big bucks, and it can ruin your reputation as a scholar, artist, or blogger if you get tagged as a plagiarist or a thief. Best to bone up on copyright stuff and avoid copyright infringement troubles. At the same time, don't be afraid to use what you need to use in the course of your honest academic inquiry and art. Carefully and fully cite the source of any copyrighted materials you use on or offline, don't copy and use too much of any one thing at a time, and then let the chips fall where they may.

Sources For Further Consideration

Without hyperbole, Jules can say that there are zillions of copyright help websites online. These two are her faves, and they are the ones she used to develop this information:

- Columbia U Copyright Advice Office - read this kind of stuffy website thoroughly, take it all in, and then check back once a year or so.

- University of Texas Copyright Crash Course - dig this happenin' flash blog and start groovin' in a legal way.

Furthermore, Findlaw.com has a pretty good layman's introduction to copyright. It also provides good introductions to patents, trademarks, and trade secrets, which are legal concepts related to but separate from copyright. These concepts are beyond the scope of this discussion, but they are certainly worth taking a look.

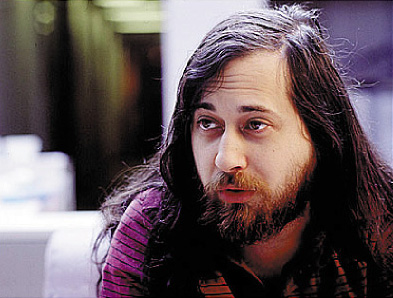

And then, of course, there's the concept of copyleft, the GNU General Public License, the Creative Commons public use licenses, and other creative approaches to intellectual property that have emerged in the web era. These too are related concepts beyond the scope of this discussion. They are designed and used to maximize the freedom of information, as in freedom of speech and not necessarily freedom from price tag. The idea for these licensing forms was first hatched by Richard Stallman, the founder of the free software movement and one of the originators of the open source idea. They too are certainly worth a look.