Addendum to ‘Paired With a Pear’

Analytical Explosion to a Poetic Experience

“It is the cognitive function of Imagination that permits the establishment of a rigorous analogical knowledge.” – Henri Corbin (Buhner, 191)

Abstract

This paper begins with an expansion on the ‘Sensing Boundaries’ assignment that was incorporated unto the final paper I wrote. This abstract and the following subsections should be read as an expansion to the final paper which I submitted in class and have also included in the appendix. The reason for including supplementary material was not, as I believe, out of necessity of clarity, but rather for the sake of upholding the specific requirements desired by the faculty.

You see, through the process of engaging Goethean Science over the last ten weeks, I came to know the methods in a way that related to my own ‘poetic’ way of analyzing the world. As I read more of what Goethean Science is, the more I was convinced that a conventional paper would not and could not capture the essence of what my relationship to my plant had become. A Goethean approach specifically avoids forceful intrusion (physical or mental), extravagant categorization, specific formula for observation, and forced observation and analysis. Instead, Goethean Science aims for a more integral, intuitive, subjectively collected observation and analysis that disregards the importance of ‘deadlines’. And if nothing else, it celebrates the unique ways in which all of us as individuals are able to extrapolate and communicate whatever it is that comes out of our exploration with our plants. I felt the artistic representation of my interaction with my plant most accurately portrayed the journey, much in the sentiment of Manuel Cordova Rios’ quote, “You must realize, my friend, that the deeper we go into this, both written and spoken words of formal language become less and less adequate as a medium of expression.” (Buhner, 190).

So when I asked my professor in class whether we had to follow the specific, bulleted format of the Holdredge paper which was the prompt for this assignment, I was shocked to hear her say, “Unless you think yours is better (than Holdredge’s).” To say one was better than the other is to say they are in comparison, and that one perspective is less valuable than the other. I set out from here with firm resolve to write what my experience with the plant was in the way that I experienced Goethean Science, not show that mine was better, but to more fully embrace the teachings of Johann Goethe. .

Though my peers and I myself agreed that the paper captured not only what Holdredge had outlined but also captured a small slice of what connections came out of my interaction with the Pear tree in a beautiful and poetic form, I was shocked again when I met with my professor for end of quarter evaluations and was told that my paper was too short, was missing components and that I would lose two credits for the quarter.

We discussed this for a long time and agreed that what I had produced had definitely lived up to what Goethean would have viewed as an in depth and wholehearted exploration into his methodology, but that the soulfully artistic and poetic approach did not live up to what the original assignment for the class was. I had created the paper as a holistic art piece, integrating all the components into an amalgamated whole. But I had missed the academic component that made it a viable work in the context of our program. Ultimately, I realized that she was right. If I fully wanted to embrace and communicate what I had learned, I had to consider the larger context of our society and the generally accepted modes of sharing knowledge i.e. academic writing. Not only that, but if I wished to integrate this process into my personal goal of becoming a teacher, I should consider the more ‘cut and dry’ way of explaining to supplement the abstract.

This has been the rhetoric for the majority of my scientific and academic career. And this experience brought the original ‘Sensing Boundaries’ story I shared back to the here and now and created a fluidity between past, present and what I’m sure will be a boundary I’m walking well into my future.

The following are the components of Goethean Science as Craig Holdredge outlines them put into my own words. They can be read as footnotes to certain portions of my original paper that I will point out through this paper. They are the more “scientific” and traditionally analytical descriptions of the process; the abstract decoded if you will…

Delicate Empiricism

Have you ever found yourself entering a situation or meeting someone for the first time and making an assumption of how it will turn out and then totally been blown away by how wrong those judgments were? You may see someone as unfriendly or snobbish and then come to find out that they are deeply compassionate yet shy. You may enter a class and assume that the subject is pointless or too hard to understand, but then find that you have a natural talent for it or enjoy the challenge that it offers you. In both of these situations, the initial perspective you took to observe the situation were limiting in what the situation really had to offer. In the same a way, too narrow of a scientific hypothesis or point of view can limit what you are actually able to observe in any given phenomenon. It’s sort of like looking for your keys and not being able to find them. It’s usually when you’re not looking that they turn up. This is what Goethe would call ‘Delicate Empiricism’. He says:

“But these attempts at division … produce many adverse effects when carried to an extreme. To be sure, what is alive can be dissected into its component parts, but from these parts it will be impossible to restore it and bring it to life again.” (Buhner, 39)

“In his efforts to learn about nature, man has cut it up into little pieces. He has certainly learned many things this way, but what he has examined has not been nature itself.” – Masanobu Fukuoku (Buhner, 39)

By remaining curious to what may come out of any interaction, you can discover a broader spectrum of what that interaction entails. When I approached the pear tree I found all my prior scientific knowledge taking a backseat to the aesthetic qualities I observed. Because I quieted the analytical part of my mind that was trying to explain all the phenomenon I observed in terms of physiology and evolutionary biology, the imagery that ultimately created my poem was given to me freely by the tree.

At this point it is crucial to remember what analytical questions and explanations you may have. As Craig Holdredge writes, “If the interaction between me and nature has no focus it can easily become chit-chat and not a conversation” (Holdredge, 31). After finding a point of interest that sparked out of observation, my prior knowledge began to seep in and shift the conversation to how my artistic, philosophical observations tied into the big picture of how nature works.

The most enjoyable of these conversations led to the part of my poem where I discuss how we “join in its reproductive process…” and spread a little “solar system” of fruit to a new place. In human terms, reproduction is often associated with love, and personifying the process for a fruit tree showed me how love and connectedness is the goal of the plant, ultimately.

Delicate empiricism can mean so much more than that. It’s not simply avoiding dissection or manipulation of nature, but is more about engaging both halves of your brain, emotional and logical, for observations that have both insight and meaning. And an effective way to do this is to approach cautiously, and through time, determine what course of action is necessary to answer your questions.

Engaging the Conversation

Delicate empiricism is how we engage in conversation. It’s like making small talk. You may ask someone, “How’s the weather?” knowing full well what the weather outside is like, but it’s a prompt to gage how the person is feeling, what kind of mood they’re in, if they even noticed the weather, how present they are in the current moment, and various other things. And you never know for certain what the answer may be. They may say something that catches your interest and prompts a whole new set of questions, and before you know it, you’re talking about how Roman art deco has influenced the outcome of the last World Wars. Oh, there’s no telling where you could go!

So once the conversation is started, it’s important to keep this delicate empiricism in mind, or you may go too far down the rabbit whole. Just as a conversation can end if you go off on a tangent for too long, it’s important to relate your questions back to the big picture of why you’re talking; and that’s to get to know each other better.

What comes in key here is to listen. If you go through a whole conversation thinking about what you’re going to say next, you won’t really hear and respond to what the person just said. It’s important to let the conversation be steered by both parties involved. Holdredge calls this attentive listening an “unframed mind”. It’s sort of like looking at the sky on a starry night. If you’re trying to focus on a faint star, it’s best to look just to the side of it and not directly at it (because of the way cones and rods are arranged in the eye). By not focusing directly on the star, it comes into clear view. Avoiding to sharp of a focus while listening or observing while still keeping it in the back of your mind allows you to notice new aspects that tie into the greater focus.

Throughout my observations, I had two things in the back of my mind, that is; how the pear tree and each component of the pear tree reflect the universal patterns we see through all of nature such as fractals and the golden ratio; and how these structures show that cooperation and interconnectedness are as intrinsic as these universal patterns. That is what I was curious about. The various ways that these jumped out at me are the imagery throughout the poem I wrote, some more related to those ideas than others. I simply took what came to me and found the degree to which it fit into that framework. Some images didn’t fit at all, but I kept them in because they helped paint the bigger picture of what the pear tree was to me. In that sense, I kept the conversation going, because I took what the pear tree said and continued with it until something else came up that fit my paradigm. These were the “Ah ha!” moments, and the others were the “Hmmm…” moments, that invited further probing.

Exact Sensorial Imagination and Living Understanding

For me, this is the really fun part, where images not only for poetry but for artwork emerge, and I began to imagine the subject as a whole, and further into what it’s essence has to offer us as people and beings on this planet. The process here is really just picturing the subject in your mind as best you can, remembering of detail of color, curvature, and even smell. If you do this every time you come back from observing the subject, a picture forms over time of its different stages. You may see a plant as it changes through the season or is it sprouts from a seed, starting from the first image you made in your head. You may even see the subject as an amalgamation of all these stages, and there’s something truly magical in that. It becomes a subject that transcends time and has all the power and potential of its entire life combined into one. Holdredge describes this as the place where we see the plant or subject as the living creature it is. I see it as its ”greater purpose”; the lessons, insights, or wisdom that its process unfolds in human terms. Hendri Corbin described it as the mundus imaginalis, the “world imagination”, through which the true nature of the world is perceived (Buhner, 189).

Your mind creates an image. As you try to imagine it as precisely as possible, the influence of the subconscious will still take hold and alter it in certain ways. Think about dreams for a moment. Most every dream contains some sort of abstract phenomena; a rose colored dog singing, the outside of a building rippling like water, people’s faces changing while you talk to them; whatever it is, dreams more often than not contain everyday objects with supernatural properties. What many dream scientists and mystics interpret this as is the emotions of our subconscious mind expressing themselves through physical phenomenon in our dreams. Every object, place, and face in our dreams was constructed by our mind, and the otherworldly occurrences that happen to them were the work of the mind as well. Dream interpreters and scientists as well as many people’s personal accounts testify to the fact that messages were communicated through certain dreams. By decoding the emotions that may have cause some supernatural dream occurrence, the message being expressed by the subconscious can become clear. For example, seeing a dog bark without any sound coming out may mean there is danger you are aware of but are ignoring. Or if you have a dream where you’re pregnant, it may mean that you feel you are nurturing something good in your life.

By creating an image of your subject in your mind repetitively and intimately getting to know it, you may observe changes in it that are influenced by your feelings at the time. Holding on to that feeling and then tracking down what makes you feel that way, whether it be in your personal life or in regards to the subject itself, it may reveal a thought process lying hidden deep. Bringing it to the surface may cause a revelation, further connecting the dots for you, a missing piece of the puzzle. This “pregnant point” as Goethe would put it leads to key insights. This exact sensorial imagining is one way to do it. Largely, it allows the you to think about the plant in a different way, aside from strictly word based or thought-stream based, and view the subject in a different light.

“The aim is to think about the phenomenon concretely in imagination, and not to think about it, trying not to leave anything out or to add anything which cannot be observed. Goethe referred to this discipline as ‘recreating in the wake of ever-creating nature.’ Combined with active seeing, it has the effect of giving thinking more the quality of perception and sensory observation more the quality of thinking. The purpose is to develop an organ of perception which can deepen our contact with the phenomenon in a way that is impossible by simply having thoughts about it and working it over with the intellectual mind.” – Henri Bortoft (Buhner, 190)

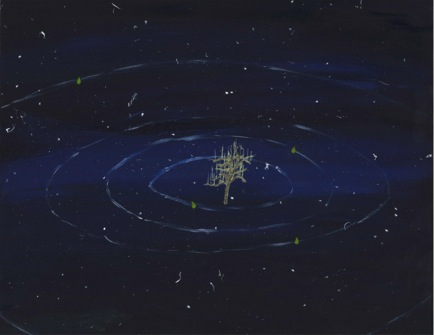

I find when this happens that my imagination instantly shoots away once I have an image of the plant in mind. It takes the plant and puts it in a landscape or breaks it apart into different colored segments, seeing inside the tree and all its little parts. Or it holds together in a steady state and I can rotate, enter inside, shrink, grow, animate before another image sweeps it away. I try not to control it so much, as Bortoft recommends, but to simply get a fair enough image of it built in the time before my imagination really takes over, because the benefit from it is that the images my mind creates around it are usually profound or useful,l if not interesting, in understanding my relation to the plant or its relation to the world. Thus the painting in figure 1 attached in the appendix. This image floated along when I was doing this exercise. Originally I had a whole different landscape planned, a fairly standard, realistic representation of the tree. I wasn’t quite satisfied with the way it was coming out. Sure, it looked like a pear tree, but it didn’t have the feel of the pear tree I’d been hanging out with. Then, as I was painting, I closed my eyes to try and really make a vivid image of it as best I could. I figured, if I’m going to paint it, at least I’ll try to get it as close to looking like the tree as I can. In that moment when I entered a new level of detail, another coated on top, then another, and all of a sudden the background I had been imagining ripped away as if someone had pulled the tablecloth from under my meal and the tree went spinning into a darkened space, a void, with subtly illuminated red and blue nebulae stretching in the far, far distance. The tree stood suspended there, totally rootless and out of place. Slowly this chasm became more illuminated as the nebulae brightened and millions upon millions of diamond stars began sparkling from all directions. The tree spun slowly and suddenly, like a sloth, the silhouette of a pear drifted across my view, left to right, and as it cleared, I noticed other tiny pears off in the distance all rotating around the tree. Most of the quarter I sat with my tree I felt like I was in a little mini solar system, with the solar systems of other trees floating nearby. I included this imagery in my poem, and when I found myself in this place totally unexpected in my imagination, I felt that ya, this is my tree.

It helped strengthen my metaphor that we are star stuff, and that we’re a small scale reflection of the large scale. And it was a lot of fun being whizzed away by my imagination through the cosmos to a little corner of the universe where there’s a tree for a solar system with rotating fruit.

Another process came out of this that was less about specific images and the feel of my specific plant and was more about what the life of a pear tree was in general, observationally speaking. As I read Goethe and Holdredge, I was excited to find they used a similar practice as me with exact sensorial imagining and living understanding; they like to envision the organism over the course of its life, through all its stages. Its easy to perceive plants as inanimate objects sometimes since they grow on such a different time scale as us, but one viewing of time-lapse photography of the rainforest or the Appalachians through the seasons shows us just how ‘animalistic’ they are, like in this video from the BBC, link provided in the bibliography (Planet Earth).

“The plant begins to reveal itself as a process. When we begin observing, we have many separate images, and we have to overcome the separateness to begin seeing the plant as the living organism it is. The life of a plant plays itself out in the ongoing unfolding and decay of organs (leaves, stockes, flowers, etc.). We are presented with a drama of transformation that we can enter into. But we can’t enter into it through observation alone. We need to utilize our faculty of imagination to connect within ourselves what is already connected in the plant.” (Holdredge, 36)

In a short poem on the last page of my original paper is the process of the plant as I saw it with a physical, chemical, molecular point of view, the elements rearranging themselves in response to stimuli, making a sort of splash or explosion.

An interesting exercise to do as well is to imagine your body in every place that it’s ever been, making a sort of snake of you, that weaves through your daily activities, all the travels you’ve done, and then lock it in place. Imagine yourself occupying all the spaces you’ve ever been simultaneously so you’re a sort of webbing mass. That might be how an alien being who experiences time much slower would see us. Or perhaps that is how plants see us. Now imagine the webs of all the people you’ve encountered, your mother, father, friends, girlfriends, boyfriends, and see how they intertwine.

A Portrayal

For this section, I will refer you to the original paper as it most completely portrays the pear tree as was my experience with it.

I will add though, that there is a wealth of botanical physiology I would add in if not for the sake of time and length of the paper. Biology is a passion of mine, and I would encourage anyone reading this to explore further into plant biology to see just how much like each other we really are.

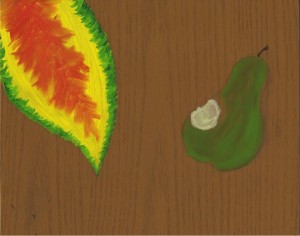

I will also include a brief description of figure 2 in the appendix. This image came out of the process of exact sensorial imagining as well. When thinking of the leaves of the tree, my mind often came back to the vibrant fall coloring, the intricacy on close inspection of which I did not anticipate in the least. A highly detailed fractalization on the borders of colors followed the veins of the leaf to such a small scale that it was hardly observable, with green around the edges, slowly fading to yellow and then to red along the central stem of each leaf. In capturing the essence of the tree and supplementing my main poem, this image seemed pertinent, portraying the “colors you (the pear) flaunted during reproductive season.”

I may also add that the tree had 8 pears upon our first meeting, all slightly more speckled than the one in my painting. The bite taken was to show the connection between painter and painted, and show the flow of nutrients between the two.

The Whole in the Part

Patterns make us feel familiar to our landscape. A morning routine creates comfort in the day. Recognizing a friend’s face brings us joy. Learning a new skill is rewarding and fulfilling. These are all patterns. Not geometric patterns (except in the case of recognizing a face), but behavioral patterns. And they bring comfort and familiarity. Being able to recognize or remember something means your neurons fired in a pattern familiar to them. Familiarity means you get to know the patterns. By getting to know the patterns of your plant, you will get to know it better. You start to see what it’s all about, its intentions and such. The plant adopts a sort of personality, or should I say, you start to see its personality. Like cactuses in a desert; they puff out a bunch of spikes to keep others away. They don’t have much water in the desert, so the cactus protects it by putting on a tough guy exterior. As Holdredge writes for the skunk cabbage, all of its stages revolve around a bud like existence. “It’s flowers are housed in a large bud-like spathe, never extending out of this mantle. Skunk cabbage blooms at a time in which most flowers, later to unfold, are still tightly encased in their buds…. (When blossomed) The flower head remains a big, fleshy bud… When the plant grows, leaf upon leaf unwraps out of the large bud…” (Holdredge, 44). And he goes on. Clearly, everything about skunk cabbage is buds! This plant has a “buddy” quality to it. Holdredge was able to see these patterns in its growth, and realize something about its personality, its approach to life.

Now, remember when I said that what I had in the back of my mind while making observations of the pear tree was to uncover universal patterns such as the golden ratio? That was right in line with what Holdredge calls ‘the whole in the part’. I was convinced by much convincing that these patterns are present in absolutely everything, so that at every scale of observation, these golden ratio fractal patterns would emerge. The main structure of the tree followed the pattern, so it was a matter of looking for miniature versions of the tree within the tree. It was easy to see how each little twig and branch resembled the main trunk. It was harder to see how the individual flakes of bark resembled the whole. The round pears were in stark contrast to the skeletal form of the branches. But the ratios were still there, expressed in different forms. For example, the point at which the bark would separate into two new pieces of park always occurred at a length on the bark, no matter what the size, that fit the golden ratio. And the thickness between the thicker bottom of the pear to the skinnier top fit the same ratio. And the length on a branch to each twig fit as well.

Of course, my scale of observation went beyond just the pear tree, so I did not discover a self contained personality expressed within the tree itself, but instead sought to find connection between the tree and all of its surroundings and insides. The one pattern that pervaded all other observable objects was a torus pattern; a donut shaped vortex. When viewed in cross section, it has two symmetrical sides with a channel in the middle for energy flow in one direction or the other. The basic cross section of the pear tree reveals the xylem and phloem through the main trunk that transport nutrients to the leaves and roots, and then two branching patterns on either side that are more or less symmetrical. Well if you view the human body from the front in cross section, we have two symmetrical halves and our intestinal, nervous, lymphatic, and aerobic systems dividing the two. The magnetic field of the Earth fits this pattern as well. The quantum forces acting on atoms works similarly too. I could see the part in the whole, and the whole in the part. The pear fit the torus, the tree fit the torus, and anything I could see or think of around me fit the torus with the help of the imagination’s perspective. This created the unity of the organism that encompassed the entire universe.

“In nature, the whole encloses the parts, and yet a larger whole encloses the whole encloseing the parts. By enlarging our field of view, what is thought of as a whole becomes, in fact, nothing more than one part of a larger whole. Yet another encloses this whole in a concentric series that continues to infinity.” – Masanobu Fukuoka (Buhner, 22)

Unity of the Organism

I wish I would have had more time with my plant beyond the ten weeks (of which many had no time for meeting with my plant) so that I could’ve got to know the plant on an individual basis more. I had a slight insight upon first meeting it on to why it’s fruit is shaped the way it is, say, opposed to an apple or orange? But the unity of the organism I did experience permeated beyond the traditional boundaries associated to organisms, and I was able to view it, myself, and all the things around me more as cells in the larger multicellular creature of which we are a part.

For Holdredge, the skunk cabbage communicated the fluidity of water with each individual component he could look at. For me, it was the torus shape and golden ratio. There are many things that unite an organism. The key is tapping into one of them. It will be a personal journey but also intrinsically interconnected to the phenomena around you. There is a common thread running through all things, and just like how the golden ration took many forms in my observation, the common thread takes many forms through what each of us can perceive as the uniting force of the organism.

Appendix

Paired With A Pear

Beginning in high school, my love for science was confronted by its inability to acknowledge human experience. Writing Lab reports for my AP Biology class brought me deep joy and satisfaction, as I would imagine a novelist does when they sit down, words streaming onto paper. I loved the “knowing of things”; explanations that go into superb detail. Not because it was an absolute or solved some mystery, but because it was a whiley story that was reasonable enough to believe. That’s what scientific phenomena were for me; that playfulness of the universe being conveyed in the most interesting and often unexpected ways.

So when I incorporated this playfulness into my writings, leaving jokes or plays on words, I was disheartened and surprised to hear my teacher, who fully understood the jokes (as any good scientist would), didn’t see their merit and docked me points for it, telling me that good scientific writing doesn’t include your voice. What was the harm? Was any credibility lost? No, the meaning was conveyed with some interesting personality to balance out the otherwise dry, boring reading of procedures and data and analysis/conclusions. That dryness was, afterall, what I had observed turned so many of my peers and friends off to science.

It was then I thought that if science can’t convey the feeling, what’s the point of science at all? It’s goal is to explain something for what it is. But thinking about love as chemical reactions derived through evolutionary selection to keep species perpetuating does not at all give me the feeling of love that I have experienced in my own life. This scientific explanation failed to fully convey what the phenomenon is.

If science’s goal is to explain what an object or phenomena is, reading an unemotional account of data collection fails to fully present what that object’s role beyond ecological, physiological relationships is. A sunset isn’t merely the refraction of light coming in at a low angle through the atmosphere; it is also beautiful. There is meaning behind these incredibly complex phenomena we have discovered. For example, the fact that the human body is composed of trillions of cells working together in ways more complex than our better perception and the fact that each of those cells has a hopelessly complex interactions of organelles inside that keep the cell going does not just give us insight into how to treat disease or enhance performance. It shows us that cooperation is an archetype throughout nature, as much if not more so than the Darwinian model of competition.

There is a personal human meaning drawn from that, one that is subjective and romantic. I believe all of science contains these gems of wisdom waiting to be extracted from the stories that nature is telling us. That is why I propose to draw up a method of teaching for when I have my own classroom that uses “Scientific Storytelling” to offer children lessons to help them enhance their own lives along their personal journey. It took me a while to get to this point, however.

After feeling disheartened with the sciences out of school, I was turned off to it even more when I got to college. I parted from my root in science and began exploring the arts much more. I was driven by the reasoning that music had conveyed truths, of situations, of places, relationships, and the world in ways that had always been significantly powerful for me. And later in my life, works of art such as paintings, sculptures, or dance really captured what that something was. An abstract dance recital where the dancer depicts the love story of a tree and a pond most beautifully conveyed this relationship in nature that a scientific paper could not.

This intuitive approach to learning sank in deeper and I began to experience the world more purposely subjective than I had before, finding what meanings or what memories and feeling that an encounter provoked in me. Or what meanings I thought were being conveyed in my day to day life. The idea of experiencing your waking life as it were a dream was a profound learning tool for me. Interpreting your everyday life the same way you would the abstract symbolism in a dream was a very poetic way of encountering the world. I began writing poems and having paintings come to me in visions. My creativity flowed into song writing, word games with friends, new interactions in relationships, new explorations into nature.

Yet this whole time I was still very much interested in scientific writings, following journals on quantum physics, cellular biology, ecology, neuroscience, relativity, astronomy, and anything and everything else in between. I still enjoyed that knowing of things. But this time it was on my own terms. I found my own meanings in it that would be “inappropriate” to include in the writing itself. I had freedom to construct my own stories of what we were in the cosmos and why we are here on this planet. And I had good scientific explanations to back them up. But they were also presented as art. That was the focal point of my work at this time. There was the subjective work that I had created; a painting or a story that could be interpreted the way you want, but was supplemented by the information and experiences that had brought me to that place.

And that is what has brought me here, to this class, to be writing about a pear. When I finally decided I could go back to school and enjoy the sciences for my own enjoyment, I chose to go to The Evergreen State College because they would likely allow my own spiritual intuitions to influence and integrate with my work. And so far, that has been true. It was over the course of my first year that I formally developed this idea of “Scientific Storytelling” as the pedagogy I am shooting for in my career as a teacher. So naturally when I saw the program As Poetry Recycle Neurons it seemed like a perfect fit.

So why am I writing about the pear, you ask? Well I’m getting to that…

The Pear

So sensuous a fruit it is. Curvy and bottom heavy, it looks as though it needs a hand to cup there, supporting it as it droop in the twiggy branches of the tree.

Thinking about an apple as I walked by, it (the pear) pulled me in.

An apple; so noble and in perfect balance

A representation of the universe in it’s full. A spheroidal torus hanging in orbit around the planetary system that is the tree. Syspended in a space of its own, hanging by stem, connected to the rest of the tree. Waiting for us to grab it. It wants us to grab it. By design, pretty, hanging there so vulnerable, politely, yet its gravity pulling me like a magnet; my eyes light up.

You

Real eyes

Realize

Real lies

The fruit is there for you, no price, no bargain, nothing asked in return. It simply wants to be eaten. All it hopes for is for you to take its seeds and spread them elsewhere. But at no cost to you. In fact, it benefits you. a delicious meal full of nutrients. All you have to do is eat it. Which you ought to anyways.

An intimate bond is formed with the plant. You join in its reproductive process, taking the seed of a solar system in your stomach.

THIS shows you the goal and meaning of the universe: LOVE

Work together cooperation

Is the way

To show love, experience it, be aware of it more and more in all its forms

Cause – – – it’s all around you

The red apple, in cross section shaped like a heart

Shiny

Smooth

Orb hanging like a planet

A nutritious reappropriation of the soil

The elements of the earth made just for you

“The apple of knowledge”

Then there’s the pear.

In contrast to the perfect sphere of an apple, the pear drupes in a peculiar way.

While I feel the apple in my heart chakra, my third eye, and my crown

I feel the pear in my sacral and solar plexus

It is an erotic fruit, simply put

I love the specifity Mr. and/or Ms. And/or Mrs. Pear. You choose this shape, rather than another, like the sphere of an apple, the triangle of a strawberry. You are drooping and curvy… seductive. And that is bold.

And as fall comes, your leaves –

Red spilling out of the veins into yellow/green. A speckled pattern of black dots mimics the giggles bubbling out of the sappy wood – it has been a job well done.

You shed the colors you flaunted during reproductive season, and have opted for the comfortable brown robe. Time to bundle up for winter and sleep.

You don’t seem sad at all that your babies are gone. Humble and proud that they have gone out into the world to find their own –

Your fractal forms the picture of life

What would have been straight lines, predictable

Now curve and bend from life’s experiences

External lungs hide what I have inside

Peaks and valleys of twiggy branches visualize a symphony

Every scale of observation reflects to me the universe

Glass window panes install themselves between your veins

I asked you to speak to me today. Tired and fatigued, I knew not what to write. What would you say?

I am open minded and open hearted. You, the pear, contain knowledge and wisdom.

—

And that concludes the poem that came out of my time spent with this tree. Did that do it for you? Do you see the whole pear tree streaming through your mind with every memory and experience you’ve ever had with one racing along beside it? Ya, I knew it would. No need to tell me.

The assignment was to let a plant “choose” you and then sit and engage in conversation once every week or so. All of these thoughts just came flowing as I sat there with this pear tree. Some new, some old ones I’d had around for a while, but the tree reminded me of them, and they all came together to make sense, at least to me. And I’m sure with a little scrutiny and exploration of the pear tree, it would start to make sense to you too. Point is, I got to know myself through my time with this tree. I saw the tree as a reflection of myself. And if it’s a reflection of me, then I must be a reflection of it too. “Two things that are equal to another thing must be equal to each other as well.” The tree and I are the same thing, and I started to view it as me. Since the tree is a part of its surroundings, since it is made of the dirt around it and the air it swirls in, then those are a part of me too. We are in fact sitting there, engaging in conversation with each other, not only in the words I’m saying or thoughts in my head, but also with the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen we are having. We are sitting there breathing each other’s air. This conversation is very intimate and eternal, for it’s always been that way with trees and humans as far as I can tell. Furthermore, to back up and emphasize my connection even further, I look to knowledge from scientific research that suggests all matter is made of atoms. Protons, neutrons and electrons, swirling around each other. So if you look past the differences in our anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, we are just simple amalgamations of these simple building blocks. And those building blocks were all once contained inside a star that exploded some 6+ billion years ago. So if I contemplate that while I am sitting there eating a pear, digesting its nutrients, disseminating it into new cells for my body, I can’t help but to feel that we are the same thing. And so the thoughts I’m having must be the same thoughts that the tree is having, and the thoughts the tree is having I must be experiencing too, and so we are sitting there having a conversation with ourself.

—

What personal meanings await us in the world if we approach it critically and emotionally?

Be emotionally critical.

There’s no reason not to.

As a citrusy sun drop drips down to dip itself in the oceans of the time, the impact sparks a reaction that lasts 40 years or more. The slow controlled explosion within seeds’ cells expanding outwards over the decades. Stretching branches hanging in the air trace the path of this explosion.

Does a tree not resemble a mushroom cloud? Huh, a life giving explosion…

When we eat our food, our cells act as little bioreactors, facilitating explosions of energy from these tasty treats. The heat released from these microexplosions radiates through our bodies. It’s what keeps us warm. And so that heat is shared between the sun, the tree, my body, and the bodies I come in contact with. Warmth ~~~

—

I visited my tree last week. It gave me a contented hazy, nod, saying hello as best it could from its dream state. Snuggled up in the dripping wet rain, the brown robe was working as it listfully dreamt of the fruit it would produce next year. It was warm as well.

Fig. 1  “Cosmic Botany” Acrylic on wood panel 10×12

“Cosmic Botany” Acrylic on wood panel 10×12

Fig. 2  “Leaf Me Alone” Acrylic on wood panel 8×10

“Leaf Me Alone” Acrylic on wood panel 8×10

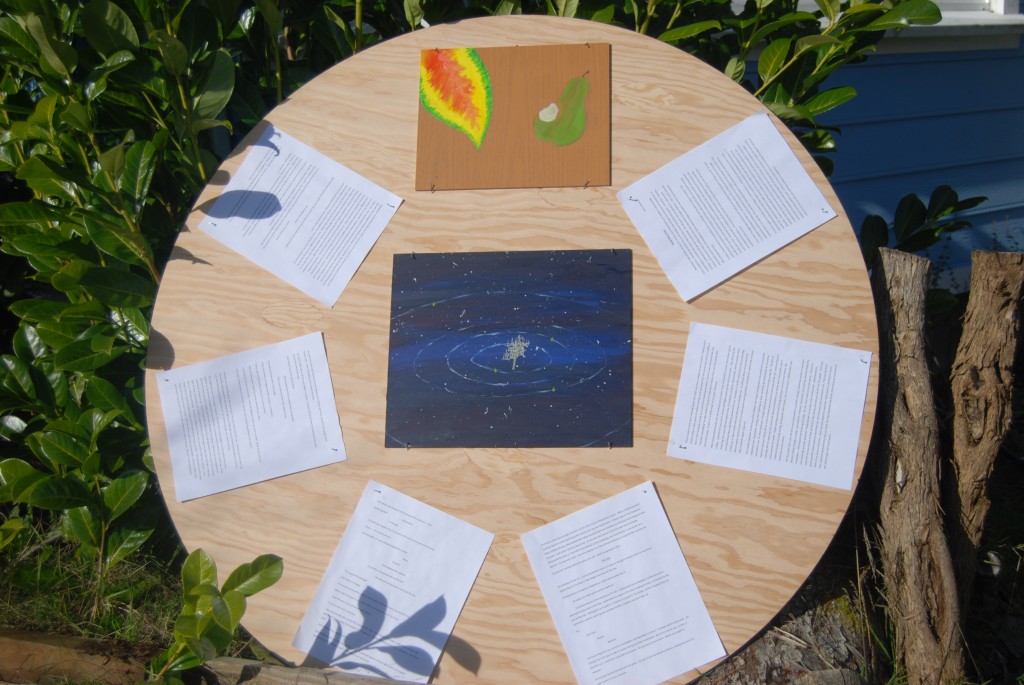

Fig. 3  “Lotus” Mounted acrylic on wood panel and paper 3′ diameter

“Lotus” Mounted acrylic on wood panel and paper 3′ diameter